Australian industrial stalwarts Severed Heads have returned to Oxford Art Factory in Eora/Sydney, and back to their hometown with a show that feels as strange, joyful, and life-affirming as their legacy deserves. It is fitting that four-decade-plus-old group who always prioritised independence, art and experiment over commercial concerns would say yes to a show organised by the DIY Ashfield record store, Prop Records.

“We’re happy to return to the area where we started back in 1982,” frontman Tom Ellard tells me afterwards. “Cycling back to this original place feels like it gives us more control over the history, which could otherwise be a dog’s breakfast of this-then-that.” For Ellard, the night was less about nostalgia than about connection. “Here too are younger people starting up, and although our history has little relevance to their future it’s a friendly moment to share. Community.”

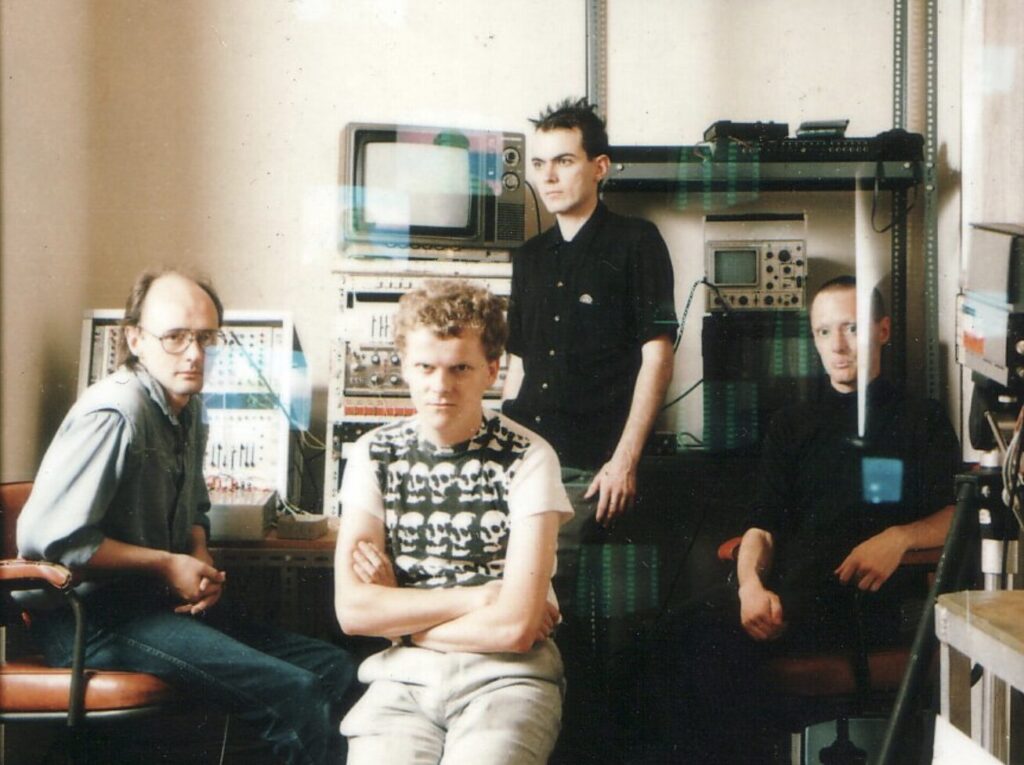

In 2025, Severed Heads live are Tom Ellard with long-time collaborator Stewart Lawler, whose presence brought a playful, grounded energy to the set. Lawler’s roots in Australian electronic music run deep. He has been a member of Boxcar, Now Zero (currently in resurrection talks), and kosmische homage Klaus. While he’s too busy to be a full-time Head, on stage he’s the perfect foil: someone who is a clear fan of the band, who can literally leap with glee simply by being there.

Severed Heads were as much an A/V project as a band, which is still clear tonight. A trance-infused rendition of ‘Hot With Fleas’ unfolds against video of flying forks, before the surreal picnic-themed nursery rhyme warps into a fever dream. They end the set with ‘Lamborghini/Petrol’ and ‘Dead Eyes Opened’, the night reminds everyone in attendance just how elastic and enduring these songs remain.

Severed Heads began to coalesce in 1979 and, from 1981 onward, have been led by Ellard. They are one of the longest surviving bands to emerge from the Australian avant garde and post punk scenes which make the last 45 years of their history difficult to summarise neatly. That said, the band dabbled with chart success throughout the end of the 20th century. ‘Dead Eyes Opened’ may have been obscure on first release in 1984 but a remix got to number 16 in the Australian charts a decade later. ‘Greater Reward’ (1988) and ‘All Saints Day’ (1989) found a home further abroad becoming bona fide dance hits in America.

To speak to Tom Ellard is to realise he is an artist who has never been comfortable standing still. Not only has his work (with Severed Heads and CoKlaComa and an artist in his own right) spanned decades, formats, and technologies, but it has always been marked by a willingness to test limits, embrace accidents, and question the systems that shape how music is made and heard.

Labels like “pioneering” or “innovative” tend to cling to the past, but Ellard’s practice has never been about doing the repetitive work that tends to shore up these reputations. What matters is moving forwards. What also matters isn’t polish or perfection, but curiosity, humour, and a refusal to treat music and art as something fixed or finished. In conversation, Ellard is sharp but unpretentious. He has little interest in myth-making instead reflecting on the act of making as something provisional, flawed and alive.

Severed Heads’ early work in the 1980s is, however, often labelled as pioneering though Ellard is quick to push back on this particular label. “That only applies after some time, much the same as ‘vintage,’” he says. “It’s a bit desperate to claim anything until it’s had some audible impact.” Still, he looks back “very carefully” where there are moments he admits might qualify: playing around with a Roland TB-303 on the 80’s Cheesecake (1982) solo album making him a peer of Charanjit Singh in the proto-acid house stakes, or ‘Gashing The Old Mae West’ (1986)which linked electronic industrial music with Steve Reich-style tape loop experimentation. For Ellard, this was never simply a matter of using the tools at hand. Experimentation came from limits guiding design, or from “just trying a stupid idea” and stumbling into something that worked. That instinct continues as his attention is now on creating games and virtual environments. “If it’s hard then you are on the right track,” he says. “If it seems effortless, you’re just treading water.”

The relationship between chaos and order is central to Ellard’s work. Technology has shifted, but he rejects the idea that chaos has been tamed. “Maybe people think it’s now been ‘solved,’ but all that means is you’ve adopted a wider norm. The highlights in the history of music production are mostly mistakes [caused by] drugs and people with a sense of humour. Not ‘accurate soundalikes’.” He doesn’t romanticise limited tools either, though he admits their constraints can be useful: “It just means you don’t have enough self-control and need a machine to be your dad.”

Change and reinvention have always been baked into Severed Heads’ catalogue. ‘Dead Eyes Opened’ first appeared on the Since The Accident tape (1983) when the song was added at the last moment to use up leftover space on a C60 cassette. When a label asked to turn it into a 12″ single, Ellard and producer Patrick Gibson took the multitracks into M Squared studio to revise it. There are also several versions of the track ‘Petrol’ (1985). It feels like creative evolution. The track changes with time. Ellard explains that “there’s a couple of different processes going on here. When we play live we often rebuild/re-present the track and video. Not being able to play a unique version of a sequenced track by hand, we’ll remix or rework it to, for example, be ‘a USA’ version or something that presents a new angle on an old track. There are also music labels that want it harder or faster.”

Often the label will release their own version. Ellard expresses detachment to some of these. “Sometimes I just wonder why some music has got my name on it at all, as I had absolutely nothing to do with it. It’s disturbing when you hear your work scrubbed clean of individuality, turned into dog food,” he says. “It’s like somebody evicted you from your house. Everything that made it yours is gone. ‘Dead Eyes Opened’ has been remade and reformed and bent and stretched so many times it’s become a thing unto itself. Like Play-Doh. The most amusing part of that being how listeners pick whichever version that goes with their first pimples and staunchly defend it as the best, most authentic version.”

Nostalgia doesn’t sit easily with Ellard either, though he acknowledges the paradox of having built the exhaustive Sevcom (Severed Communications) online archive of Severed Heads’ history. For him, nostalgia is a limitation: “It sees everything from a fixed aspect.” A museum, however, is different, it documents change. “I’d like people to see how far we’ve developed over time,” he says, “so that when people ask me about 1982, they might understand that I don’t remember very much, having continued to exist to 2025… and beyond!”

Commercial success, too, is something he approaches with a healthy dose of scepticism. In the 80s and 90s Severed Heads occasionally found their way into the charts, and some writing about the band suggests there was a certain pop cohesion in the sound during that period. The band’s rare brushes with this success, he argues, had little to do with the music itself and everything to do with the industry machinery. “The charts are funny things, I’m not sure if they were ever real,” he reflects. “Our success was at its peak when we were least involved.” He claims that a 1994 CD-ROM release was boosted not by any musical breakthrough but because it suited Sony, politicians, the ABC and even venture capitalists to push the format at the time. “Anything to do with our music? Naaaah.”

Severed Heads, Ellard has declared more than once, are dead. Yet the project keeps resurfacing, with shows this year in London and Sydney. What sparks each resurrection is rarely part of some grand plan, more a response to the right invitation. “The main thing was a call out from Vinyl On Demand,” he explains, recalling the German label that issued a Severed Heads box set back in 2008. “2008 was a really sad period for us with no one interested, so we were really happy to have that reboot. In 2025 we said hell yes to V.O.D. When The Jazz Cafe also said hello that felt like an honour, jazz folk are pretty tight about who’s cool and not, plus it helped pay.”

There is no surprise then that there have also been recent offers from the US and Europe. But Ellard is wary of repeating the long, exhausting tours of the past. “It brings back some bad vibes, we don’t want to retread all these years,” he says. “It felt like a broken loop to end in London.” Sydney, meanwhile, proved complicated: a festival offer was turned down when organisers refused to provide a video screen. “That meant they didn’t understand us,” Ellard shrugs. “A small venue on Oxford Street is a much better loop, even if it’s small, it’s to scale.”

Sevcom began as a practical workaround. It was a mid-90s label and online hub to bypass gatekeepers and put Severed Heads’ music, and later video and media experiments, straight in front of listeners. It was simple, direct and ahead of its time. Today, though, that terrain looks very different. “I had a very good grip on how the internet worked back in the 90s and 00s,” he says. “Slowly it’s gone over to the dark side… except that there are big pots of money involved.” He accepts a kind of weary compromise. Bandcamp, he allows, is “close enough” to what Sevcom tried to be; and artists must “work with your audience wherever they are. It sucks that some use Spotify but that’s not up to me to thwart them. Well, I did for a while but relented.”

He considers the scale of the problem the web created. “I’m forced to be cruel here. There has always been more music than listeners. There have always been unsold records in the bins at the record store.” The internet didn’t solve that mismatch, he argues, it amplified it, “fooling people into uploading hours of video, music, writing etc., pretending that there is a so-called ‘long tail’ effect. It’s one half of communication with a phone line that goes to voice message.” Layer on algorithmic attention economies that favour dopamine hits, and the promise of distribution begins to look like extraction.

So what’s left for the maker? Ellard’s answer is blunt and oddly energising: “Level up to The Now. Stop talking about ‘albums’. Stop making ‘rock music’. Stop living in the last century. Go to the very edge and start there.” In the same breath he also jokes, “Where is that edge? Why are you asking an old man?”

Sevcom was a small, stubborn attempt to carve out room for strange work. The platforms that followed rearranged that room into a marketplace. Ellard’s stance now is less a nostalgic manifesto than a continued experiment: keep tinkering, keep moving, and try to make things the machines can’t quite measure.

That raises the question of longevity, what lasts, and what’s designed to vanish. Ellard shrugs. “It’s often not my call,” he says. “When we made our 1982 Blubberknife cassette sculptures it took weeks of hard work. Of 200 physical objects only one example remains, in bad condition. In the 90s when I burned CDs they were good for a few years but have faded and probably won’t play. And only if somebody still has a CD player.”

Formats, he suggests, all fail in their own ways. “Streaming only lasts as long as you pay the fees. Maybe vinyl lasts the longest, so long as you don’t mind the wear and dust and crackle. The Smooth Arabic Surface acetate from 2008 was hand made in small quantities and acetates wear out very quickly. All in all, digital downloads are your best bet, stored on multiple drives. My masters are on a RAID drive which backs up copies immediately and does a health check every day.”

But permanence isn’t just about the medium. It’s about memory, and here Ellard’s pragmatism hardens into something close to fatalism. “I expect that we will be forgotten, because so many other things are forgotten. To be remembered I’d need to use weapons and tactics to climb over other people around me to gain memory space. But it’d all end up distorted AI bullshit anyway.” He pauses, then softens the blow: “Does it matter? I make my little museum, a few people look at it, then the power goes off. So it goes.”

Dive further into Severed Heads’ music here and further into their history here