I’m sure everyone reading this knows the sudden jarring sensation of getting half way through a joke or an anecdote before realising what they’re saying is completely inappropriate. The ill-judged story at a wedding or wake; the “too soon” pub joke; the “you had to be there” tale from a crashing bore, all leading to the panicky thought: what is this blasted drivel I’m spouting and God help me while I grimly soldier on to the appalling punch line. But more to the point, why did this embarrassing act of verbal hara-kiri have to be my opening gambit to musical legend and hero, Scott Walker?

It’s probably sheer nerves but as an ice breaker I find myself describing an imaginary film scene that his new album Bish Bosch made me dream up: “…so you’ve got an entire orchestra full of zombies all murdering each other with their instruments. And in the end it’s just a musical saw-playing zombie hacking away at the conductor.”

And my voice fades away to a querulous whisper of self-loathing: “And in the audience there are a load of zombies saying, ‘Brahms! Brahms’ instead of ‘Brains…'”

Then just as I’m about to burst into tears and run off, Scott Walker slaps his hands together and emits a large, warm laugh: “Hey thanks, that’s the next album written!”

It turns out that not only is Walker one of the most vital, challenging and engaging figures in 21st Century popular music, but he also has a very sharp and generous sense of humour. He pretends to make a note to himself: “Now I’ve just got to get Peter [Walsh, his long-standing co-producer] to find some zombies for me…” Scott Walker will slap his hands together delightedly and laugh a lot during our hour long conversation.

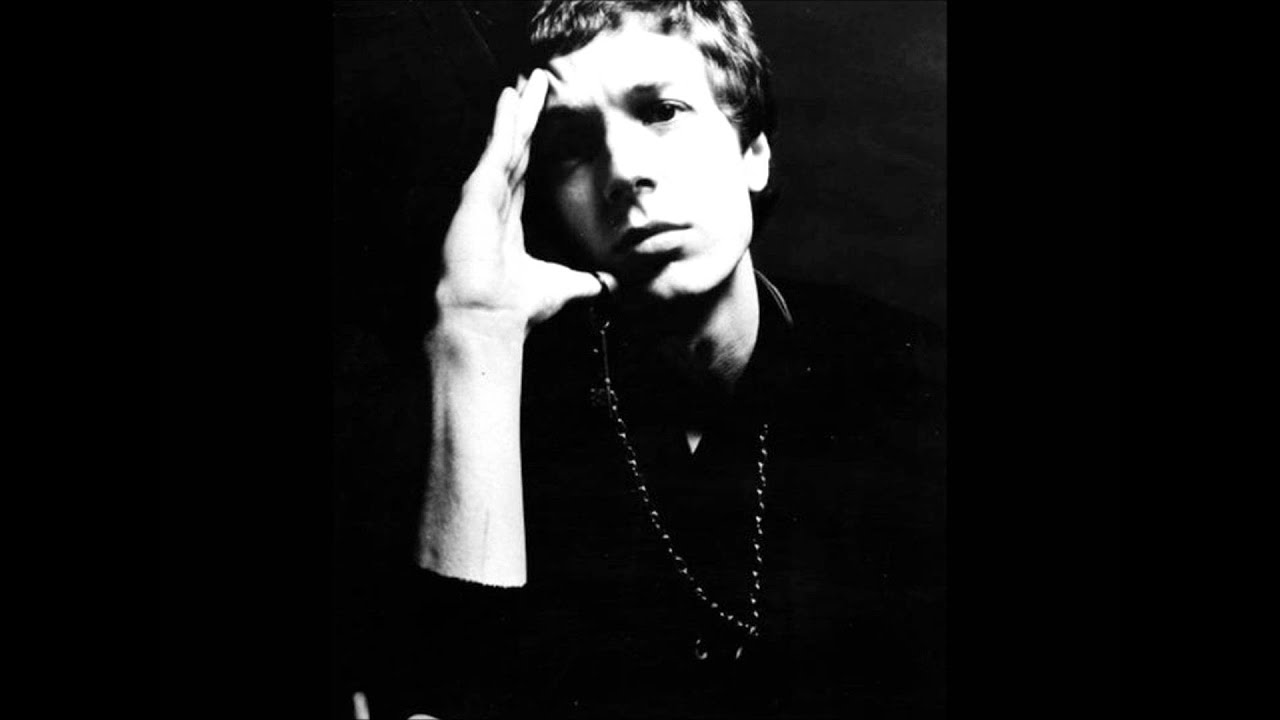

Walker, a 69-year-old New Yorker who grew up in California and moved to Europe well over 40 years ago, has ploughed one of the most singular furrows seen in modern music. In the broadest possible terms his career can be divided into quarters. Scott One was a member of extremely popular 1960s group The Walker Brothers, who were so big that they even eclipsed the success of The Beatles in 1966. Scott Two was a solo crooner who released a quartet of peerless self-titled LPs that painted rich vignettes of life in the late 60s; kitchen sink dramas channelled via the spirit of Jacques Brel. Scott Three was a near washed up figure who dampened down his creativity with marathon whisky binges while releasing unsatisfying solo country and western and MOR albums and joining in a cash-motivated Walker Brothers Reunion. Scott Four was and remains a highly misunderstood left field artist with no peers who has recorded four of the most challenging ‘rock’ records to be released on relatively large labels: Climate Of Hunter (1984), Tilt (1996), The Drift (2006) and now this week Bish Bosch.

However, while there’s more than a little truth in this overview, the true picture is a lot more complex. For example, he displayed a knack of introducing the disturbingly counter-intuitive and a sense of the uncanny into his song writing right from the get-go on tracks such as ‘The Plague’ (1967). And while a lot of his output released during the 1970s and 1980s is hardly what you’d call essential, by the same token, this is when he recorded some of his most beautifully realised material. Belatedly, many music fans have been questioning received wisdom and seeking out his astonishing contributions to the Walker Brothers’ swansong Nite Flights (1978) and his wonderfully chilly solo album Climate Of Hunter (1984). But as well as this, even his disparaged MOR career contains such broken-hearted, saloon bar gems as ‘No Regrets’ and ‘Cowboy’. [See David Peschek’s notes on Scott Walker Myths below.]

The lesson here is to ignore received wisdom and to discount the urban myths. It’s the only way you’ll even start to get to grips with Bish Bosch.

I could use up the word count for this entire piece ten times over and still not do this album any justice. On one of many levels this is a monumental study into the boundaries of language; a cartographical study that pinpoints where it breaks down into chaos, gibberish, animal noises and fart sounds (more about this later); while this itself can be read as a metaphor for the perceived collapse of society, art and the self. Books could be written about its dense modernist wordplay which is loosely reminiscent, in several key respects, of that in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Reviewers will tie themselves into knots trying to describe this deadly sonic funnel web of industrial beats, atonal metallic guitar, cosmic lap steel, electronic noise and clash of four-foot-long machete blades (more of this later as well). Puzzle-loving listeners will search frantically for clues to deeper meaning in the lyrics voiced by multiple narrators including a minor saint who spent most of his life sat up a pole, the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu and Attila The Hun’s disfigured dwarf jester.

Do I like it? I think so. Is it any good? Ask me again in 2015. Is it the most devastating record of the year? Undoubtedly. Two things that are immediately clear is that Scott Walker has produced an impactful piece of utterly unique pre-post modern art and that he remains a visionary in splendid isolation, with the few foolish enough to presume kinship with him easily revealed as clowns, ironists, fuckwits and coat tail riders by comparison.

You’ve said that you have to wait a long time for lyrics to come to you; that it’s a waiting game. How long did it take in the case of Bish Bosch?

Scott Walker: This time I set aside a year, which normally I don’t do. I just thought I’m going to try and see if I can speed up the process by not doing anything else. So it took me just over a year to get the lyrics and everything done, which is lightning speed for me. But I really had to wait and wait and wait almost every single day for the words to come.

Earlier this year your manager released a statement saying that Bish Bosch left off where The Drift finished. To what extent is that actually true and does the new album finish a notional trilogy?

SW: Well it feels like that, but I don’t think it’s literally true; they’re not joined together. We have developed a style. And we’ve been elasticating that style, pushing it to its limits, and that’s why I think people can hear this same sound going across three records. It’s possible that this is the last time we’ll try this particular atmosphere and we’ll try something very different next time. But Bish Bosch is also very different. There’s a lot of bass on The Drift and Tilt but on this one we’ve used the bass only here and there. That was because we were trying to get a vertiginous feeling where the bottom drops out from under you, leaving you with nothing to hold onto for a lot of the time. And when the bass comes in [smacks hands together violently] it’s a very welcoming thing.

Some of the dark atmospherics on the album made me think of the more ambient end of dubstep. To what extent do you keep up with new music, say for example, on the Hyperdub label?

SW: I know Burial. I know all that stuff. I try and keep up with so much stuff, whether it’s Burial or a hit record off the radio.

On first listen, I actually found Bish Bosch more harrowing than most current releases in the fields of black metal, noise, industrial and power electronics, where causing distress or discomfort to the listener is often an integral part of the aesthetic. To what extent do you know these genres, and to what extent are you trying to put your listener through the wringer, as it were?

SW: I’m aware of the sort of music you’re talking about, black metal and so on. I’ll dip in and listen to that kind of stuff but my music is coming from me – I don’t know exactly how, but it is coming from me. Generally with [noise and power electronics etc] everything is going one way. The vocals and the sound are only going one way, and I try to give several layers to keep you interested, more like in a painting perhaps. Maybe there will be an underlying seriousness, maybe there will also be some humour, but there will be a lot of stuff happening at the same time. And I think that’s the main difference between what I do and black metal for example.

Where did the album title come from? I believe it has something to do with an idea of a giant female artist…

SW: I knew I’d be playing with language more than I had on any of the previous albums. I wanted the title to introduce you to this kind of idea and reflect the feeling of the album, which was [claps hands briskly] bish bosh. And we know what bish bosh means here in this country – it means job done or sorted. In urban slang bish also [phonetically] means bitch, like “Dis is ma bitch”. And then I wrote Bosch like the artist [Heironymous]. I was then thinking in the terms of this giant universal female artist. And this idea continued to play through the record in certain spots.

The architectural critic Jonathan Meades said something interesting to me recently: “Heironymous Bosch may have been warning us against Hell, but he had a hell of a time warning us against it. He really enjoyed himself!” Do you enjoy making these records? Do you have a lot of fun making them?

SW: Oh yeah! Yeah, we really do. But they’re difficult too. If things aren’t going well then they’re difficult to achieve, but it’s 50/50, because we have a lot of fun and a lot of laughs as well. [emphatically] You’ve got to have that. Like I said, it can’t just go one way. Good art never goes one way.

I guess propaganda goes one way and art is more multi-directional, more open to interpretation. This brings me to the sense of humour on the album… I probably listened to Bish Bosch about four or five times… reeling… slightly agog… before I heard the jokes on it, but then I realised that there were probably 11 or 12 rib ticklers on it. Would it be fair enough to say that in some respects this is the funniest album you’ve written?

SW: Most broadly humorous yes. There is humour running through The Drift as well. It’s there. You have to look for it… get on our wavelength [laughs] but it is there.

Forgive me for saying so, but I think maybe my first reaction to the album was the more honest, and I have to question how funny a listener could be expected to find these jokes in the context of the harrowing music. Isn’t it fair enough to say these jokes are more absurd than funny?

SW: Yeah, they’re more absurd.

And absurd humour or absurdity is another feature of existential crisis isn’t it?

SW: It’s absurd. It’s Kafka-esque in its absurdity. Franz Kafka would read his stories to his friends, and when they weren’t laughing he would get furious. It occurred to me that maybe it’s the same thing with my music. No one thinks of [Anton] Chekhov as a comic writer, but he certainly thought he was. Who knows?

An analogy that I thought of was one regarding some of the films of David Lynch. For example you could watch the film Eraserhead all the way through one day and find it a grim and relentless experience, and watch it another time and find it ridiculously funny…

SW: Yeah, that’s exactly it. That’s it. Eraserhead is a great example as well because maybe, it’s still his best film.

But there is one genuinely laugh out loud moment on Bish Bosch and that’s in the way the album ends with ‘The Day The Conducator Died (An Xmas Song)’, a track ostensibly about the overthrow and then rapid execution of Nicolae Ceaucescau and his wife Elena, which ends with sleigh bells and the first few notes of ‘Jingle Bells’. I genuinely LOL’d. What things make you laugh? Any books or comedians?

SW: Gosh… [pause] I’m trying to think… [massive pause] What makes me laugh? [massive pause] We’ll have to come back to that… [we never do]

The opening track on the album ‘See You Don’t Bump His Head’ is a line uttered by Montgomery Clift to soldiers putting Frank Sinatra’s body in the boot of a car, edited out of the final cut of From Here To Eternity. You looked up to Frank Sinatra as a singer when you were younger. How much did you learn from him in terms of breathing and phrasing, and does any of that still apply now to the newer style of vocals that you do?

SW: Well, very little now. Back then his phrasing was his key ingredient. No one else could do it like him. No one else could tell a story like him. Within the confines of the American standard, you could listen to his breath control and just hear how good he was. A simple thing like singing, “I love you.” A lot of singers today will sing, “I…” [gasps for air] “love…” [gasps for air] “you…” [gasps for air] You wouldn’t say it like that if you were having a conversation with someone. The words would flow together, “I love you.” He would sing words as if he were saying them directly to the listener. He knew that you couldn’t just throw this stuff together. But this music is so other to that kind of stuff that the rules don’t really apply any more. These songs aren’t standards.

Well, no, they’re not, but you’d still never, ever, ever hear Scott Walker take a breath on record would you – and that’s whether you’re singing ‘Make It Easy On Yourself’ or [Bish Bosch track] ‘Epizootics!’

SW: No, you wouldn’t, but then you wouldn’t hear many singers from that time take a breath. You wouldn’t hear John Lee Hooker take a breath either. A few years ago I was watching Tom Jones doing a concert and even though he had the mike right next to his mouth, you still didn’t hear him take a single breath… because it wouldn’t sound right to him. And that’s the difference because today on some records the breaths are as loud as the notes. [groans asthmatically] You can hear people wheezing in and out!

On ‘Corps De Blah’ you have hyper intelligent and provocative word play which is juxtaposed with these really coarse bodily noises. Fart noises. The sound of excretion basically. It sounds almost like you’re having fun at your own expense. Are you trying to deflate the perceived pomposity of your own lyrics?

SW: In a sense it’s used to cause a break… Actually it is to cause a deflation of the lyrics, you said it better. It’s a break, so you don’t end up thinking, ‘Oh my God… what’s he doing now? He’s overdoing it!’

Who stepped up to the mike? Or who backed up to it?

SW: [laughs] We’ve taken an oath that we’re not going to reveal the sources of those noises.

Well that’s fair enough, but something doesn’t add up here for me. You obviously spend a lot of time creating certain noises on your records and your Foley work is very painstaking and very accuracy focused. I mean, we all know how you built a large wooden box and rested it on breeze blocks and then spent days dropping concrete on it just to represent the sonic idea of a pea under a thimble [on the track ‘Cue’ from The Drift]. So unless you drafted in Le Pétomane to record the sounds, it just feels a bit lackadaisical to me, and also I dread to think what it would be like in the studio if you had to keep on doing take after take of these terrible noises until you got the fart exactly right.

SW: [laughing] No, no, no! It wasn’t that elaborate.

Ok, from one bit of Foley work to another… Where does one get musical machetes from?

SW: Oh, the nightmare machetes? I got them online. I was looking for the heaviest ones I could find. Of course when they arrived everybody panicked, especially when we took them to the studio. Out of everything we’ve done in the studio, this was the thing that people I’ve worked with hated the most and they couldn’t wait for us to get them out of there. They really panicked. I mean they are monstrous to look at; the blades are about four foot long. I knew I needed a lot of weight otherwise it would sound like kitchen knives. Yeah, I got them online… they’re the most dangerous things I’ve ever used to make music with.

What qualities make Peter Walsh the ideal co-producer for helping you realise this kind of music?

SW: He has a good sense of humour, which is great, and he’s a very steadying influence in the studio, so everyone likes him. That’s the main thing. He’s a great engineer. And together we’ve created this sound which I would describe as… well, this may sound fanciful but nevertheless this is how I think of it. In its purest sense, ever since we did Tilt, the music we’re making is meant to be an aural version of the H.R. Giger drawings for Alien. It always sounds to me like those look.

I met someone who said, ‘It took me two years to work out if I thought The Drift was brilliant or just ridiculous; and then another year on top of that to work out if I actually enjoyed listening to it or not.

SW: Yeah, they cause extreme reactions these albums, so I’m never surprised when I hear things like that. I can always tell if a guy’s not really willing to go there, I can always tell that, but I’m used to whatever reaction these records provoke.

I know you don’t do much singing in between albums, so you’re going to be out of practice when it comes round to recording time, but do you still have to put a lot of effort into getting your voice emotionally neutral, or is this a technique that you find it easier to achieve now?

SW: Well, it’s changed on this record because most of this record isn’t emotionally neutral. Most of these songs are character driven… not that you want to overdo them or risk ending up impersonating people. But on a song like ‘Zercon’ [‘SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter)’ the 22 minute centre piece of Bish Bosch] you can’t do that without some extreme singing and going to some extreme places.

Since the release of The Drift, two folk bogeymen have raised their heads in this country; chavs and hipsters. I’m not sure to what extent either of them actually exist but people in the media are obsessed with these terms. Hipster has become a pejorative, derogatory term, but would I be right in presuming that you connect to this term in a more old fashioned, positive way, with the hipster being the kind of person who hips you to cool art and cool music.

SW: Are you talking about the one song where…

‘Epizootics!’

SW: Yes. I’m going back further beyond the beatniks, back to the hipsters, back to the days of Cab Calloway. And they would say, “Epizootics!” And click their fingers. People would naturally presume that I would be talking about the study of plague – which is what the word means literally – but actually I was using it in the same way as the hipsters used it, to mean cool. I wanted to reach back to this idiomatic language they had.

What’s funny about that song is the fact that suddenly out of nowhere for one of the first times ever, suddenly there is this massively signposted piece of hot jazz…

SW: There were six of us playing ride cymbals going tshh-ch-ka, tshh-ch-ka, tshh-ch-ka tshh-ch-ka, tshh-ch-ka, tshh-ch-ka.

It makes me laugh because you’ve spent so long saying, ‘I’m not a jazz musician, this is not what I do.’ And then there it is.

SW: Yeah, but only briefly, and it’s only there to give an example of this idiomatic world that these characters are in, but then it really changes quickly to beats. You know: ba-da ba da-da! ba-da ba da-da!

It’s probably worth saying at this point, however, that no matter how complex or forward looking what you do is, that you’re not a jazz musician – that’s not the tradition you’re from, it’s pop and rock music you’ve taken to breaking point.

SW: Yeah, of course. The jazz is only there for a second. It’s more for the atmosphere of that world. Because it’s over exaggerated for starters. Real jazz wouldn’t have six guys playing the ride cymbal.

Does it irritate you when your music enters the general consciousness; like with The Drift ending up being boiled down in the popular narrative to the album with the guy punching the giant slab of beef on it? [On the track ‘Clara’, Alasdair Malloy is credited with “percussion and meat punching”] Do you worry this will become the album with the farting and the machetes?

SW: No. These kind of people who think of it that way obviously don’t want to invest their time, so it’s useless worrying about what they think. The people who are going to like it are going to like it and with anyone else I just have to… suck it up!

Are you opposed to the idea of synergy? Do you feel like your art – and by that I mean specifically what you’re trying to do with Tilt, The Drift and Bish Bosch – can only be expressed in the form of music released on album?

SW: Well, not necessarily. I think they could probably exist in the theatre as well. A couple of years ago we did this thing at the Barbican [Drifting And Tilting]. It was a mixed bag. Some of it worked quite well, so I can see the work maybe existing as theatre pieces.

The other side of that question deals with the fact that you really seem to have branched out a lot over the last few years. You recorded the Pola X soundtrack, you’ve written songs for Ute Lemper, you’ve curated the Meltdown Festival, you’ve worked in contemporary dance and ballet, you’ve done Drifting And Tilting. Have you enjoyed the diversification process?

SW: I love doing it. I’d like to do more of it. I’ve got a couple of things lined up for 2013 and 2014, which are pieces for festivals in Australia, and the people at the National Concert Hall in Dublin have offered me the chance to do something.

Can you say now, at the age of 69, what the two or three great and simple images in the presence of which your heart first opened are; or even if this quote from Albert Camus which was printed on the back of Scott 4 even still pertains to you?

SW: Well, the quote still pertains to me, but I can’t remember any more what they were! It was so long ago…

Why are there so many references to Hawaii on the record?

SW: It’s only on that one song.

Well, from Here To Eternity is set in Hawaii.

SW: Oh yeah. Ok. I didn’t even think of that.

Have I fallen down the rabbit hole into Scott World here? I’m trapped in Scott World and I’m seeing bloody connections that don’t even exist everywhere.

SW: There’s too many Hawaiians! Too many Hawaiians! [laughs] Yeah, you’re in danger of going down the rabbit hole. No, it’s really only on ‘Epizootics!’ that I had this idea about waking up from a Hawaiian nightmare. I wanted to connect it into an entry into this idiomatic world [of hipsters].

You’ve mentioned the idea of nightmares. I believe you’ve suffered terribly with nightmares over the course of your life, was there a specific recurring dream you had?

SW: [laughs] This whole album… that’s my nightmare! No… thank God… thank God, those nightmares seem to have gone away over the last decade, I no longer have those intense nightmares that I used to have.

Maybe you’ve finally syphoned them off onto your last few albums.

SW: Yeah! I’ve got them on record! No, I can’t remember what the nightmares were like and I don’t want to remember what they were like. Awful.

You’ve said in the past that you’ve suffered from depression and Brian Gascoigne [musician on The Drift] said something in an interview which I found very illuminating about your process. He said that you believe that in order to convey strong emotion in a song you feel that you have to be experiencing this emotion. Now to me, this sounds like an unhealthy way to be. Would you agree?

SW: I would agree, except it’s not true. I never write autobiographically first of all. Maybe what he was referring to is that a lot of the time when we were mapping things out – I had to go over to his place to use his machine before I got my own machine – to sketch things out on his computer. I just think he read the situation wrong. He assumed something merely because I wanted a certain feeling to happen in the music. I would say: [voice becomes stressed out] “Can’t you understand what I’m saying here, it has to be done this way. It has to be done like this.” [claps hands together violently] And I think he might have been feeling the strain a bit and interpreted what I was doing as a personal thing, but it isn’t.

So you don’t even go through these extreme emotions by proxy like a method actor would?

SW: No, not at all. My periods of depression were the worst in the 1970s; I don’t really have a lot of that now.

So the fact that you’re not particularly prolific has nothing to do with the fact that you find the recording of this material particularly draining or unpleasant?

SW: No, it’s just getting the quality of it up. It’s just about having the patience to watch the thing unfold and sometimes you just get tired and give up.

So because of the song ‘Zercon’, I need to clear my computer’s browsing history. I was looking up every word or phrase I didn’t recognise on Google, including the term “grostulating”. I’m still not sure what it means but I had to stop researching as I was in danger of getting sucked into a swirling vortex of male pornography and grot.

SW: Hmmm… [pause] Oh yes! Grostulating! I use this word about Mikael Gorbachev and a summit he had with Ronald Reagan. The idea in the song was about reaching different kinds of heights and those two were having a summit, so that’s why I put them together. I’m kind of as fuzzy as you about what it specifically means but I think generally speaking it has something to do with being buggered.

The photos that I saw suggested that if one is grostulating it means that one is fully ready to receive a guest, if you take my meaning. I read a fantastic article by David Toop recently in which he said that he could imagine a world where Big Louise: The West End Show was bigger than Queen: The Musical and that your influence would be felt on the X Factor, where hapless contestants would be made to try and tackle ‘Cue’. Does it annoy you or do you find it frustrating that your stock isn’t perhaps bigger, that you haven’t reached an even wider audience for your most recent work?

SW: Well, I know my stock isn’t going to get that big, and I’ve accepted that fact. Every time I make a record I accumulate a few more people and it’s a slow process but I’ve got enough people now to at least justify the expense. So as long as I can justify the expense of the records I make that’s enough, because I don’t know what else I should be doing. Well, I don’t know what else I could do that would make me as fulfilled.

After conceiving Bish Bosch in your head, which were the most difficult sounds to actualise?

SW: Pretty much through power of description and original imagining, it wasn’t a nightmare to try and get those guys to give me the sounds I needed. The smallest thing that took the most time to get right was the little ‘squeaker’ [a sound similar to a Victorian car horn or squeaky dog toy] on ‘Corps De Blah’, because each time, it wasn’t at the right pitch, it took hours just to get the right pitch… but after that it worked a treat.

You’ve moved a lot more into the realm of using electronics on this album. Why is that?

SW: On this album it was about 50/50. We’ve used a lot more electronics than we’ve ever done before but this time it was about getting the right mix. You can do it for some things but not others. People always ask about big string sections versus big synthesisers. There is nothing… There is nothing… nothing that gives you the power or the resonance of strings. A machine cannot do it. It can be loud and everything but it lacks that human touch. And that goes for all of the acoustic or electrically amplified ‘traditional’ instruments that we use. There are certain times when you have to have that feeling and other times when it’s not important.

But there’s a big difference between synthesisers and samplers though. I take it you haven’t resorted to sampling sounds?

SW: No. If I was going to make a totally electronic record like, for example, one by Burial which you mentioned before, I wouldn’t worry about it. I would make a totally electronic record – which I may still do. But for this record I wanted an organic feel which is why I use live musicians.

I know that BJ Cole is famous in his own right and an in demand musician, but I was wondering, do you not get any of your many celebrity musician supporters queuing up to be on your albums? I mean you’re very much a musician’s musician, among other things.

SW: [laughs] No! I think people would dread it. I cannot imagine why they’d want to put themselves through it.

It’s a shame because I have this idea of you doing a version of Bonzo Dog Doodah Band’s ‘Intro/Outro’ with you saying: “And here’s Thom Yorke on rhythmical meat. Nice punching there Thom. And here’s Jarvis Cocker hitting a large wooden box with a brick. Drop it like it’s hot, Jarvis…”

SW: Ha ha ha! That’s a funny idea, hmmm, I’ll have to give it some thought… Listen, I don’t mind calling anyone in, I don’t mind calling any instrument in, I don’t mind calling in anything if it’s in service of the lyric. I will do anything the lyric calls for. If it calls for Mantovani strings I’ll have Mantovani strings…

…but so far it’s just that the lyrics have called for more abstract things.

SW: Exactly. So far the lyrics haven’t called for me to get in touch with Shirley Bassey.

Why are people acting like the concept of flagpole sitting, the central image in ‘Zercon’, is really arcane? Didn’t David Blaine, the popular, idiot’s magician of choice perform an act of what was essentially flagpole sitting in Times Square, for a global audience of millions, ten years ago?

SW: David Blaine is the modern equivalent of Saint Simeon Stylites; that is true. Him and the guys who climb up very tall buildings… human fly characters, they are the modern flagpole sitters, you’re right.

In the song ‘The Day The Conducator Died’, the overall vibe I’m getting (from the protagonist Nicolae Ceaușescu) is one of bewilderment from beyond the grave that his people turned on him, one of outrage that he wasn’t allowed time to compose himself before he was shot, and one of anger that he was buried on the other side of a path from Elena, not next to her. I’m not trying to tempt you saying something outrageous here, I’m just curious, is there any part of you that feels any empathy for these people like Stalin, Mussolini or Ceaușescu?

SW: [emphatically] Well, no. I kind of felt something for Mussolini’s girlfriend Clara because she was just so… I don’t know… taken in. But no, I don’t feel anything for those guys because they’re dangerous clowns. It’s hard to feel any sympathy for them. Well, there is one thing you can say about them… a lot of dictators were artists earlier in life but they were artists who went wrong in certain areas. They had one bad night… [thumps palm heavily and laughs] and that was it!

It’s weird with Ceaușescu. Do you think he genuinely had no idea how much the people despised him at the end?

SW: Of course, it came as a total surprise to him because he was totally deluded. They all live like that and then the end comes… the brutal end… and they can’t believe it. It happens to all of them. “What went wrong?! What did I do wrong?!”

When I told people that I was coming to do this interview, you wouldn’t believe the number of men who wanted to come with me, to hold my dictaphone…

SW: [laughs with mock lasciviousness] Did they now…

They wanted to be my ‘assistant’ or whatever – all of them guys. Do you feel like you’ve finally, after all these years, swapped one bunch of obsessive fans for another? Screaming teenage girls for angst-ridden middle aged men who read too many books on existentialism?

SW: I don’t know. The Barbican thing came as a real surprise to me. When I looked round the audience I didn’t see anyone from the 1960s. I mean, the people who were round in the 1960s hate my music! It was a pretty good mix of people but I don’t think there was anyone over 50.

Do you still have the key to the Quarr Abbey where you sought refuge with monks at the height of your fame? When was the last time you were tempted to make good on the Abbot’s offer of an open door; the offer of sanctuary?

SW: No, I lost the key years ago.

Did you study Gregorian chant there?

SW: Yeah, I did, but I couldn’t stay too long unfortunately. We had obsessive fans and they discovered the monastery and they were ringing the bell the whole time. We were plagued. And eventually I had to leave. But I learned a little bit from this guy who was there. It was a phase I was going through, but an interesting one.

Are you still reaching for something that you haven’t attained yet… do you have the equivalent of a Finnegans Wake that you’re still aiming at?

SW: No. Well, I’m probably not going to attempt these language things again, but I’m always reaching out and waiting for the next thing to occur to me. I don’t know what I’m going to do next but I’ll start next year in February. I’ll sit down and see where it takes me.

Well, if it’s like Bish Bosch or if it’s a completely electronic album, or whatever it is, I can’t wait to hear it.

SW: Thanks very much.

Those wanting to read more on Scott Walker should pick up The WIRE related anthology of essays edited by Rob Young, No Regrets which includes the David Toop essay mentioned above. Read more Scott Walker interviews at Rock’s Backpages

From Pop To The Avant Garde? Scott Myths Which Need Debunking, by David Peschek

Another decade, another Scott Walker record – except, for someone widely thought of as a recluse, and whose recording process involves painstaking longeurs – a kind of pensionable Kevin Shields – his work-rate seems to be increasing. Or maybe this is just one of the myths about Scott that’s all-too-easy to debunk.

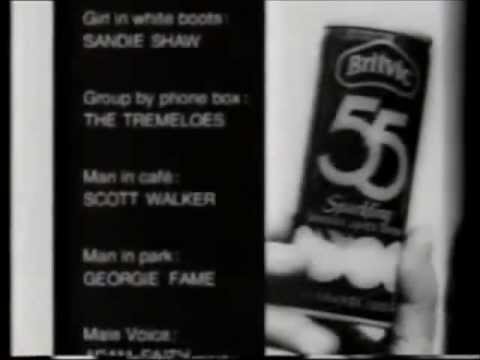

In 2000, preparing for Meltdown, he told me with a wicked glint in his eye that “people might die” waiting for his new album. From Climate of Hunter in 1984 to Tilt in 1995, there was silence, a silence which filled gradually with rumours, conjecture, stillborn collaborations – oh yes, and Scott’s Orson Welles moment (well, one of them) – his brief appearance in a mid-80s ad for Britvic orange juice

But since Tilt, there have been his cameo on Nick Cave’s soundtrack for To Have And To Hold in 1996, the soundtrack for Leos Carax’s Pola X in 1999, the two songs written for Ute Lemper’s album Punishing Kiss in 2000, his curation of the Meltdown festival in 2000, We Love Life, the album he produced for Pulp in 2001, his own The Drift in 2006, the ballet score And Who Shall Go To The Ball, And What Shall Go To The Ball? the following year, the concert Drifting And Tilting (in which Scott was involved but didn’t perform) in 2008, and now, in 2012, Bish Bosch – its title very possibly an allusion to/joke about – amongst other things – its maker’s work rate and perfectionism.

But it isn’t just his work rate that needs to be examined…

There’s the idea of old Scott – ballad singing Scott, crooner Scott, teen heart-throb Scott – and later Scott. Rubbish. Certainly, the Walker Brothers sold more records than the Beatles in 1966 – sales figures hardly matched by their swansong album Nite Flights (1978) – whose opening quartet of songs (the first Scott had written since being crushed by the commercial failure of Scott 4 and ‘Til The Band Comes In) are generally heralded as the lift-off point of Scott’s, ahem, avant garde, phase. To be crass, it’s like being asked to believe that one of those perfectly nice boys from One Direction turned into a composite of John Zorn, Diamanda Galas, Ligeti and Sunn 0))). I mean, really…

Exhibit A: ‘The Plague’ (b-side of ‘Jacky’, 1967) – listen particularly from 2.46 when the strings drop out and mostly it’s just percussion and The Voice – this wouldn’t be out of place on track 5 of Bish Bosch, ‘Epizootics!’ (Epizootics [from the Greek]: ‘a disease that appears as new cases in a given animal population, during a given period, at a rate that substantially exceeds what is “expected” based on recent experience’).

Besides – you could transpose snatches of lyric from anything from ‘Archangel’ (which dates back to the first Walker Brothers period) to any number of songs from the solo albums (‘Angels Of Ashes’: “There’s no starting or stopping…/ well that’s alright for some who can hang the absurd on their wall/ If your blind hands can’t grope through these measureless waters you’ll fall/ You’ve been following patterns and fleeting sensations too long/ and the fullness that fills up the pulse of durations is gone…’) onto any of the later, ‘experimental’ albums.

Then we come to the idea that the early Seventies ‘MOR’ albums are rubbish… Well, yes and no. Arbiters of the far-flung reaches of the experimental do tend to dismiss them – as if that weren’t reason enough to go back and listen to them again. Scott himself is also in print as being less than fond of them, although – as with Tom Waits, albeit to a lesser extent – you do have to take what he says about certain things with a pinch of salt. When I prompted him about some of the tracks listed below, he admitted they weren’t entirely without merit.

Exhibit B: Scott …Sings Songs from his TV Series (1969) is worth owning on vinyl for the gatefold sleeve alone. On it Scott’s pictured wearing the key to his room in Quarr Abbey, a monastery on the Isle of Wight where he retreated from the white noise clusterfuck of teen-pop stardom to study Gregorian Chant – an obvious influence on his ‘late’ vocal style.

Exhibit C: ‘The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti’, from The Moviegoer, an album of film themes made by a devoted cineaste – partly for the tension between spare and lush redolent of both the 60s solo records and the late work, but mainly because it’s gorgeous:

Exhibit D: Randy Newman’s ‘Cowboy’, sung by Scott on his first album of 1973, Any Day Now (harking back to his version of Newman’s ‘I Don’t Wanna Hear It Anymore’ from the Walker Brothers 1965 debut Take It Easy With… and forward from that to the Midnight Cowboyish hustler anti-hero of Scott’s own ‘Thanks For Chicago Mr James’, from 1970’s ‘Til The Band Comes In).

Exhibit E: ‘Someone Who Cared’ (from the MOR-countryish Stretch, 1973 – possibly his least loved record), written by Del Newman, who also produced the album – could be an out-take from Scott 3:

Bish Bosh is out now on 4AD. Thanks to Rich Walker for his assistance