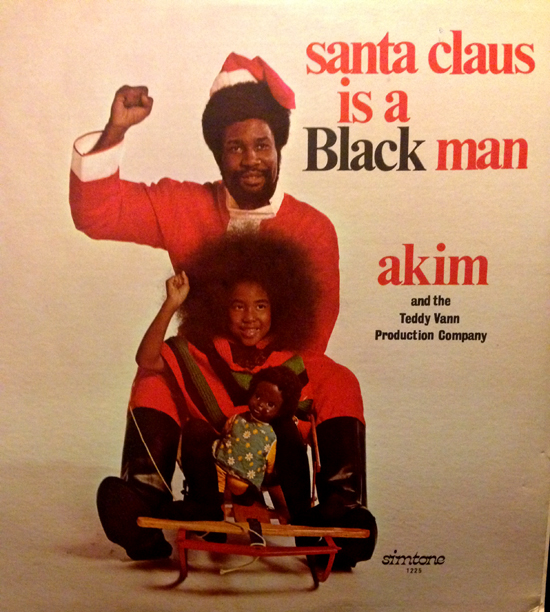

The cover shot for Santa Claus Is A Black Man tells you everything you need to know about the song. Teddy Vann sits on a sledge, dressed as Santa, with his five year old daughter Akim. It’s cute, funny and festive, and seems entirely silly – until you realise both have their fists raised in a black power salute.

Released forty years ago this Christmas, ‘Santa Claus Is A Black Man’ by Akim & the Teddy Vann Production Company is pure novelty: a soul funk retread of ‘I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus’, sung by a little girl to her daddy. It’s festive fluff, complete with none-more-70s asides ("I can dig it" says Teddy, when he’s told about the handsome, black Santa with an afro, and adds "Right on.") It’s a cute Christmas song, sang by a child and for children. Which makes it easy to overlook just how pioneering that made it. This was a novelty Christmas song for black kids released in 1973, when African American children were completely left out of traditional festive imagery; it repackaged the ethos of blaxploitation music for pre-schoolers, attempting to give black children a piece of Christmas they could actually relate to. The song is a key point in the life’s work of Brooklyn musician and polymath Teddy Vann, a fascinating and overlooked figure in late 20th century African American popular music.

Vann, who referred to himself as a "born again African", had written the 1960s novelty hit ‘Loop De Loop’ for Johnny Thunder, and would go on to win a Grammy for his song ‘The Power of Love/Love Power’, a huge hit for Luther Vandross in 1991. He also dabbled with performing, appearing on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand before deciding he preferred life on the other side of the mixing desk. What’s notable about his career, which spanned decades, wasn’t necessarily his recorded output, but the huge strides he took throughout his life to give young black people a culture they could relate to, and provide an alternative to the eurocentric imagery that dominated in 60s and 70s America. That was especially true at Christmas, with its cherubic blonde nativity angels and rosy-cheeked Santa Claus.

"His intention with the song, I’ve come to learn, is that he wanted to create the same type of message for African American children," says Akim, now in her 40s. "They could also have images that were associated with things that were beautiful, or things that were good, or things that were exciting. American slavery gave birth to the definition of the word "black" becoming something that was not so good. If you look it up in the dictionary, "black" is going to have all these negative connotations, and unfortunately as an African American, as a black child or as black people, you can’t help but be affected by that. He was redefining what it meant to be black, in terms of positive, beautiful imagery being associated with that word."

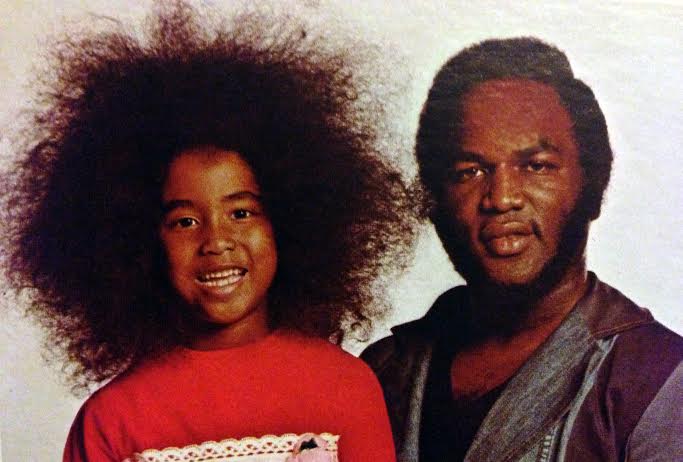

As children, Akim and her siblings were walking testimony to Vann’s multicultural ethos – they each had traditional African names, and grew their hair into huge afros. All three appeared as regulars on Sesame Street for over a decade, making them some of the most visible black children on American television.

Akim, who has inherited her father’s fiery enthusiasm for empowering young people, was five when ‘Santa Claus…’ was recorded, and is rightly proud of her contribution to his work. "It’s something that every single year people play," she says. "I remember it being played on a radio station when I was younger, but when it’s your parents doing things, you never think it’s a big deal. Now, as an adult, having children of my own, it’s definitely something that’s completely endearing – that he would do something so special, and that it would have such longevity."

Vann’s mission stretched beyond Christmas duets with his daughter, however. In the late 60s he wrote and produced a series of comic radio plays called The Adventures Of Colored Man, starring a young James Earl Jones – the voice of Darth Vader – as a black superhero, solving crimes with his "super-ebonite brain". The stories are funny and surreal, but never militant or even especially overt in their message. Vann’s work was rarely about confrontation tactics, instead he was attempting to normalise black imagery. "He had another story he recorded when I was eight called The Beautiful Black Princess," recalls Akim, "a fairytale about a princess who, like in all the other stories, was being pursued by serious suitors. The story occurred in Africa, and at the end, instead of picking the wealthy person, she picks the most intelligent. His intention was definitely to give another definition of beauty. He wasn’t staying ‘instead of’, it was ‘in addition to’ – everyone should be able to have images they can relate to that are positive reflections of what they see when they look in the mirror."

Despite annual play on black radio stations in New York and New Orleans, ‘Santa Claus Is A Black Man’ remained a relative obscurity for thirty years, until kitsch filmmaker John Waters included it as the closing track on his 2004 novelty compilation A John Waters Christmas. Vann was far from thrilled.

"I was in my dad’s car when John Waters called and asked for permission to use the song," says Akim, "and my dad did not give him permission. Apparently they’d already pressed up the CDs. I don’t think they thought that my dad would say no. Here’s another example of my father never compromising his ideology or his beliefs. If you look at that compilation of Christmas songs they’re funny, they’re jokes, it’s slapstick humour, and my father’s album was not a joke, and his song was not a joke. He didn’t want to be guilty by association, he did not want his song in that company." Vann went to court in an attempt to stop the release rather than have his song dismissed alongside Rudolph & The Gang’s ‘Here Comes Fatty Clause’ and Alvin & the Chipmunks’ version of ‘Sleigh Ride’.

It was one of several points in Vann’s career where he willingly shunned commercial opportunities in order to stay true to his ideology. "He defined what success was for him," says Akim. "For him and for our family, my dad was very successful, the most important things to him were family and his credibility. What people would call "selling out" in terms of allowing someone to misrepresent for money, that was not important to him. I mean, he wanted to make money – of course he wanted to make money, and he did – but that was not what drove him. What drove him was his family. He was very committed to his family, and very committed to empowering youth, but not on a micro level – on a macro level."

Ultimately it was Vann’s work with young people and his efforts to empower disadvantaged children that drove his creativity. "I think what most people don’t realise is that Americans get so caught up in race," says Akim. "This socially constructed disease, we get so caught up in that, that we don’t invest in our youth of all different "races". The macro ramification of not doing that is that the world suffers. Children are our resource, regardless of where they come from, and because we don’t regard all children as being equal on some level, we trample on so much invention. He tapped into youth and utilised brilliance that would have been otherwise looked over. There are so many youths who were under his mentorship doing great things today. That was his mission."

Although Vann succumbed to cancer in 2009, he left behind a sizable body of work: not only the 140 songs he has registered with BMI, or his book on maths and basketball still being used as a resource in American schools, or his perennial Christmas song, discovered by more people every year, but also in the young people whose self-image was subtly altered for the better as a result of his efforts. And none more so than his eldest daughter, who has carried on her father’s work as a mentor and life-coach for young people. "My dad was way before his time," says Akim. "This was somebody who was extremely progressive, and his ideas were ideas that were before his time, which is why the album is still extremely poignant."