Musician, sound artist and instrument maker Sam Underwood’s new album, AMS // Umber Ne is the first of its kind. Released under the MrUnderwood alias, it was recorded almost entirely with his latest mechanical venture – the Acoustic Modular System. The modules that comprise the ams (pronounced as a single word – æmz) sound like a rag tag bunch of Beano characters – Puffer, Tapper, Blower, Tumbler – and have sonic personalities to match. The sounds they make contain unruly mechanical rhythms that mirror the twanging of rulers on table edges, the jangling of bell and shell laden strings, and even a one-man band having a go at parkour. There is a chaotically walloped zither; a duet that sounds like a headbutting free improvisation between plastic panpipes and a typewriter; and all manner of pings, clops, and boings.

Underwood’s Acoustic Modular System is designed and made in collaboration with creative technologist Richard Sewell (with some help from ‘Miles The Intern’). "I’ve been building modular mechanical musical instruments for a while now," Underwood tells me over Zoom, "and it’s just an area that I really love. I like the way that you can adapt the sound directly – if you don’t like the way that something sounds, you can just modify it physically and see and hear that change. I find electronics quite difficult, because it’s all hidden away, so if I’m making a change to a value of a resistor, I don’t really know exactly what the outcomes are going to be. So that’s why it’s an acoustic system. The reason it’s modular is because I get bored! Making something big like an organ, all the keys and pipes makes it an overwhelming task. I like to be able to put an organ module to one side for a while, to go and work on a drum module."

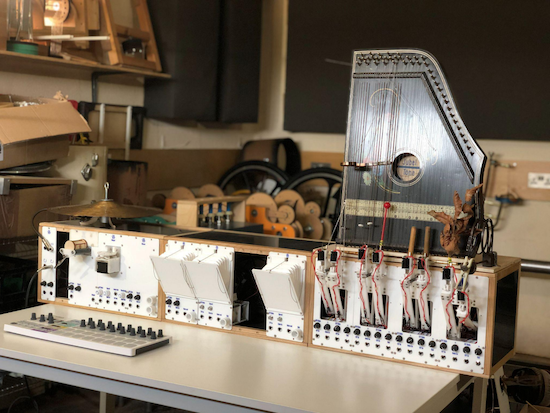

Like a regular modular synthesizer, ams uses control voltage but instead of powering oscillators and filters, it is used to fire up acoustic elements. The ams is built from three types of module: controllers, utilities and sounders. The ‘Feedbacker’ is a sounding module that largely creates textural drones (but can squeal too). The ‘Tumbler’ is a utility module designed around a set of cylindrical shakers, which ‘tumbles’ whatever items are placed on the rollers, creating rhythms. The ‘Shaper’ is a control module – a rotary proximity sequencer on which objects on a platter are read by a sensor. The ‘Blower’ is a utility module which creates air with a fan, and provides the drone air for the system. The ‘Puffer’ is a set of percussive bellows, and the ‘Tapper’ is a percussion module with posable arms.

While the occasional human performer appears on the album – on harmonium, melodica or percussion – for the most part the music is entirely made by the acoustic modular system. ‘Nder’ for example, opens with a soft hiss and whirr of air from a miniature set of pristine white, medical-looking, palm-sized bellows. A low, breathy loop begins, then a plasticky lolloping rhythm and soft thudding 4/4 drops in from one of the rhythm modules, intruded upon by an excitable brassy cymbal that refuses to stay on beat. The whole project is strangely soothing in its idiosyncratic rhythms, possessed of a certain naive optimism produced by the characters of the modules themselves; they are characterful and systematic in their own esoteric way, like mice in the Bagpuss universe.

Underwood says key to how expressive the modules are, is their "inside-outness": "If you get excited you can just push the Puffer bellows with your hand to make it parp loudly – even when it’s running – or you can yank the posable arms of the Tapper module to stop them striking, or to change where they strike,or you can cover the mouth of an organ pipe as it’s playing to bend the pitch."

He is perhaps fondest of the bellows, where in a single stroke you can audibly hear each position it passes through. "It’s a thing in organs as well," he explains. "Some organs have a tremolo bellows, which allows them to do a percussive air thing alongside the main bellows. [Our bellows] does that, but in an amazingly controllable way. However, it’s also a physical system, so it has this funny but likeable drawback, in that it has to ‘breathe in’ every so often. That’s part of what I like about working with physical acoustic stuff. Because the options aren’t endless, they are constrained."

The Acoustic Modular System is also built so that it can be incorporated into an existing modular setup, alongside other more standard modules. One motivation for this was the relatively compact scale and portability of a modular system, especially in comparison to Underwood’s previous builds like the Giant Feedback Organ, which was, well, very large. It was built in collaboration with fellow mechanical music maker David Morton, from ducting pipes that were four metres long and half a metre in diameter.

Underwood’s previous projects also include drone doom tuba group Ore, the Mammoth Beat Organ with Graham Dunning and a double-wheelbarrow musical instrument he built with Sam Cook called the Barrow Pig. He’s also created a pedal-powered, ping-pong-fuelled musical instrument in collaboration with Sarah Kenchington called Thing Thong; installed sonic vending machines that gave out hand-made instruments, and made a collection of signalling horns which were then performed with at the Fort Process festival. He also ran an event series called If Wet in his local village hall at Callow End in Worcestershire that was a sort of show-and-tell for other esoterically-minded instrument makers, musicians and sound artists.

One of his first ever forays into building sound-making contraptions was sonic graffiti, which he began doing as a teenager. He would create unassuming novel sound-making devices, such as noise makers or small audio circuits with standard headphone jacks, then zip tie them to lamp posts or Gaffa tape them into convenient cracks in walls, leaving them there for people to discover. "I would just leave sound devices in places, or go on holiday and just take one with me and leave it somewhere," he says. It’s unknown how many survive, or where they even are. It’s plausible that there is still a headphone jack in a wall somewhere, keeping Underwood’s noise-generating circuits schtum, until someone comes along and plugs in.

Underwood now lives in Worcestershire, "a little too close to the River Severn" (his studios flooded recently). He was able to build his own studio 12 years ago, after he and his friends cashed out of a successful web design business they started in their early 20s, just before the sector took off. "We set up a web design company really early," he says. "Then we got quite big, made money, and I spent that money opting out of the business and building where I live now. Our accountant said to us, ‘I’ve never ever done what you’re asking me to do for anyone who’s still in their 20s, they’re normally 55 plus and have realised, "What the fuck was the point in all of that."’ But we did it really young – canned it by the time we were 28 or 29."

Sam Underwood in his previous Glatze incarnation

Nowadays his workshop is teeming with instrument parts, some inherited tools, and various other contraptions. He says he has had to stop buying equipment and parts as he has filled all available space and was beginning to spill out into the garden. "At the moment I’ve got a piano harp in the workshop downstairs taking up a lot of space, but mostly, I just can’t help myself with brass instruments," he says. "It’s full of bits of trombone and tuba and sousaphone and god knows what else. I don’t normally use playable instruments though. I ordered a couple of sousaphones from India for a project two years ago and the first thing I did when I got them here was try to play them. They were so unplayable – I was really pleased! I wouldn’t have been able to use them if I could potentially have given them to a school."

Much of his work now is concerned with the character of mechanically produced sound, and the ways in which we can interact with these sound making devices simply by pushing, pulling, tapping, or adjusting them; and he is just about to start a PhD in modular mechanical instruments. However, it wasn’t always like this. He used to make electronic music under the moniker Glatze, which was "full on dance stuff". However, he had always struggled to understand purely electronic music making, and so moved towards circuit-bending and making noise boxes, which in turn led to (mostly) abandoning electronics and beginning to build mechanical instruments. As for the Acoustic Modular System, he likes the fact that as well as being unusual conceptually, it also looks unusual, and allows for unusual ways of playing. While there was perhaps more of a performance with something like the Mammoth Beat Organ, which required two people to grapple with an unruly machine, his new system still allows for a more interesting performance than is usual with a knob-twiddling Euro-rack gig. "I like the audience to experience the physical way in which the sound is created, as well as hearing the sound," he explains. One of the major hurdles to working primarily with mechanically and acoustically produced sound is amplitude – you can’t just turn up a knob to get the elements working together at the right mix, and instead he has to allow the music to flow with the inherent levels of his systems.

A more frequent problem with making custom mechanical instruments as Underwood does is their tendency to fall apart. I ask if this constant risk of failure is part of the appeal. "Very much so. That’s something I also like to witness when I’m watching other people play – I like performances where it’s quite precarious. Stuff goes wrong all the time. Things fall off or fall over, and it’s obvious that that’s not really meant to happen."

For now, the modules on the Acoustic Modular Synth are all in fine working order, and there are far off plans to offer them for sale to interested parties, although there are also already more novel modules at production stage. These include "a slit pipe recorder with a paper roll for pitch" and a "cow organ" – the latter of which is a ‘hand’ that tips a cow noise toy when prompted by a gate signal. "That last one might not get so much use," he laughs.

MrUnderwood’s AMS // Umber Ne is out on October 15 via state51 Conspiracy & several tracks from the album can be heard here