If you’re a fan of early dust electronica, if you wobble at the mention of Delia (gasp) Derbyshire or Daphne (gasp) Oram, if you can think of nothing better than listening to Trunk Records’ library reissues, the Ghost Box label’s haunted recordings, or any music made on creaky computers and analogue synthesisers, then let me introduce you to Ron Geesin. He’ll be very pleased to meet you.

This 67-year-old Scot, born in deepest, darkest Ayrshire during the Second World War, has had his latest album – the product of 25 years of electronic experimentation – mixed by Mark Ayres, the man in charge of the Radiophonic Workshop archives. Geesin was also championed by John Peel in the late 1960s, made a record soon after based around sounds from the body, before being brushed aside by two chaps known as Waters and Gilmour, after co-writing a six-part epic with them called Atom Heart Mother (they found his work far too wayward, the poor souls, and soon buggered off to do some dirge or other called Dark Side Of The Moon).

Geesin then made music that sounded like Kraftwerk before Kraftwerk; that sounded industrial before industrial music had been jump-started into being; that whooshed like flying saucers thirty years before Flying Saucer Attack. And now since 1986 – in between spates of composing brilliant music for schools, electronic jingles for headache tablets, and sound collages for the BBC’s Omnibus – he has worked on the beast of a project that became Roncycle 1: Journey Of A Melody, made in his converted garage in the Sussex countryside, surrounded by digital synthesisers, ancient Apple Macs, hundreds upon hundreds of tapes, and the fruits of many decades of tireless experimentation. Ron Geesin is the British hero beavering away in his garden, with wonderful theories about music, that you just don’t know yet.

But I thought he’s such a perfect Quietus sort of person – wilfully individual, incredibly inspiring, humbly inventive – that you had to meet him too. I first met Ron in 2008, while writing an article about library music for The Guardian, inspired by the trend for library records being sampled by the likes of Dangermouse and Beck. His classic 1972 album Electrosound had just been released via the Dutch Glo Spot label, and I had a perfect sunny day in Ron’s purpose-built studio, talking about avant-garde individuals like Edgar Varese and Gerard Hoffnung, playing with the black-and-green touch-screen of his Fairlight computer, and being served soup by his boiler-suit-wearing wife. With his big white beard, he looked like Father Christmas; this heavily-accented Scot also had the best laugh in Britain. He was still struggling with his life’s work, however – but this year, he finally finished it.

Ron Geesin’s Ambling Antics, from Electronic Toys: A Retrospective of 1970s Synthesiser Music

We speak again three years on, just as Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother has been made part of the music strand of the French baccalaureate. Despite his split with those famous grumpsters, Ron is happy. “It’s quite a story – I’m now in company with Bach’s Mass in G minor!” He laughs, but then settles, "Although I’d like to stand up and say look here, world, I’ve done 2,000 pieces of work. Some of which I think are much better than Atom Heart Mother but no one has heard them!”

So you’ve just released Journey Of A Melody – a 50-minute epic consisting of 16 tracks that you started in 1986. It’s a wild, wonky, wilfully peculiar electronic work, and you have said “as it grew, it frightened me so much that I had to walk away for long periods”. What does it feel like to have finished it?

Commuter/Car Crusher from 1972’s Electrosound

Ron Geesin: A huge relief! I’ve just had a big baby. That’s the danger with ideas, when you know they’re strong, but you just can’t get them finished. They lie inside and fester until you get them out. I mean, I’ve always talked about any piece of my work being an exorcism. And it is! But in the case of artists, and to quote Martha Graham, there’s only a divine dissatisfaction, because the moment you’ve got something out, you’re thinking of doing something better. Anything one does creatively is merely a rehearsal for the next thing.

What role did Radiophonic Workshop curator Mark Ayres play in it whipping it in shape?

RG: He drove this whole thing to a successful conclusion. If he hadn’t been there with his expertise, I couldn’t have handled it… It’s a bit like the Frankenstein syndrome. You build something and then you can’t handle it – it gets out of hand. I’ve always prided myself on being a one-man band from conception to reception, but I had to let go in the end, because the mixing was killing me. He was marvellous. I’d be sitting behind him, him mixing away, me leaning forward and saying could you lift those two notes there and he’d turn round, and say, ‘I’ve done it.’ It was like having a good conductor.

How would you describe your peculiar kind of electronic music to new fans?

RG: I’m an absurdist composer who has chosen to go the solo way. I was being supported a lot by a disc jockeys when I started: John Peel on the BBC in radio, and I did sessions for his programs. I would shoot my mouth off and say I was a virtuoso with a razor blade and tape. I could make tape do anything. Everything. Turning it backwards and forwards and sideways — anything you like. But going your own way is both a blessing and curse. You get the benefit of doing what you want to do, but you have no or very little feedback, because there are no colleagues. Desmond Briscoe – I remember it well – did a tour early of the Radiophonic Workshop for me, around 1966 or ’67, before inviting me to join. And I said no – I just wanted to go my own way.

A World Of Too Much Sound, from 1967’s A Raise Of Eyebrows

Why? Couldn’t you see the advantages – the money, the opportunities, the creativity?

RG: Yes, but I could also feel the possibility of being institutionalised. I’ve been paranoid about that since being old enough to talk. But yes, it put me at an disadvantage. I didn’t get that camaraderie, feedback, that pleasant jealousy – any motivated jealousy, a sense of competition. So I set up my own world – for better or worse. Although I was always jealous, or envious, of the fact the Radiophonic Workshop existed within the BBC. Producers would go to it to get the right appropriate sounds for their visual piece – they always got the gig.

What relationship do you have to their music?

RG: I think some of the Radiophonic Workshop stuff was technically brilliant, but often emotionally sterile.

What about other electronic music? Do you listen to a lot of it?

RG: No. [laughs loud and long] But that’s because… I like to let other music and sounds influence me instead. So I’m into classic jazz of the 20s and 30s, composers from different countries, like Eastern Europe and Russia. I think I once owned an Elvis Presley single, but I don’t listen to groups. They don’t interest me.

None at all?

RG: [thinks] I did order a Queen record once. I remember going to the back door of EMI of get it. I don’t know what it was about it. Something about the structure of their music interested me. But largely nothing else. In my wood and metalwork shop, I either have Radio 3 on or nothing. Radio 3 or sound of an electric drill!

Is this to not let your music be infiltrated by other sounds? To keep it pure?

RG: [laughs] Those are your words! But it’s quite possible. Jealousy can’t work if it doesn’t hear anything else successful, can it? There could be some of that! But it’d be dangerous to pick that up as key phrase, because that’s just one layer of feelings. Everyone has multi-layers of brain activity. If you look at someone and say, well, I can see three layers of brain activity there, there might actually be ten layers… no one knows where they are, or what’s in each individual subconscious. I hear that in my music too, especially listening back to 25 years of all these bloody thought processes.

[my phone starts buzzing, I apologise for the interference… Ron’s ears prick up]

RG: In parenthesis! Isn’t it interesting that all in amongst all these modern technological developments – like hi-fi, surround sound, Dolby, digital cinemas – the quality of sound of phones has deteriorated enormously. Give me a big black bakelite any day. 3 Bs, that’s good. Big black bakelite bastard – that’s 4!

How did you structure Journey Of A Melody?

RG: I had a big roll of paper with the sections described on it, but it only went two sections ahead of what I was actually writing. It was a bit like building a dry stone wall. Do a bit, look at it, move on. Or it’s a bit like looking at the countryside, when you’re going for a walk. You can see the path ahead, and your brain’s thinking, when I go over top of that hill, I might go left or right, but the closer you get, the more appears to point you where you’re going to go. It’s like that.

What comes after Roncycle 1, then? Roncycle 2, one would assume…

RG: Yes! Roncycle 2 should be, is hoping to be, the journey of a rhythm. Because from a dead straight analytical point of view, there are two components to music: melody and rhythm. Which appear obviously in Indian raga structures in instrumentation, but, of course, the joke to some extent is that you can’t have melody without rhythm and you can’t have rhythm without melody. Even when you have tabla solos – and there are records of tabla solos, I have them! – there are melodic lines going through that are inferred, but don’t appear.

You use 25 years of equipment on this record too…

RG: I do – a friend of mine said it’s kind of a history of electronic gadgets. Because it started out on the Fairlight with found sounds, and real sounds on magnetic tape. It’s 16 track not 24, as I could never afford 24 track. And then onto the Mac. I got my Fairlight [which Kate Bush famously used in her early albums] in 1981 and it cost £25,000, the price of half a house at the time. But I was doing a lot of stuff for the media, for schools programmes for ITV… I knew it would expand the palette enormously; that I could do a lot more stuff, and expand. I went through that process of playing the commercial side off against the pure art of creativity.

Solar Flares/Colossus, from 1977’s library album, Atmospheres

What library music did you do?

RG: Three albums for KPM: Electrosound, Electrosound Vol.2, Atmospheres. Then ‘Magnificant Machines’ CD for Themes International. Also TV music for schools – maths and science series, famously Leapfrog and Starting Science. They had no voice overs, just sound and vision doing the work. A producer in Birmingham would send me the 15-minute films, in 16mm, by courier. From that, I had to make some solid music, or organised noise. Trouble is, they would come first thing in morning, and I’d have to get that done by lunchtime for the courier to take it back. And that worked – that’s flying by seat of your pants. Having a purely subconscious reaction. But some of that stuff came out really good. As a library music composer, you’re a bit like a cartoonist. If cartoonist is drawing a wall, you draw three bricks, and the rest is inferred. In the same way, some pieces might just be voice grunts with a little abstract dot moving about. That’s what I loved.

Do you have any relationship at all with the Pink Floyd men now? Obviously, you’ve said that they weren’t fans of Atom Heart Mother…

RG: [pauses, starts and then stops] Ha – you can hear the hesitation, can’t you? The way I put it is we’ve drifted… not drifted, but we operate in different strati. Different layers of the mist above the earth! That’s very apt for the early Autumn coming in, these seasons of gentle mists. That’s it. [pauses] Well, I can say this… we were all good friends [at] one point or another. And if they came through my gate, I’d welcome them openly. But I’m not going to walk in their gate. Because they’ve got a three stage alarm system. And a big dog! Actually, I don’t even have a gate! I’m talking about materially, physically, and metaphorically here, obviously. And I mean it – they’ve got all sorts of protection devices against the millions of nutters clamouring to approach them! I just terminated the relationship at one point. And that was that.

Ron Geesin’s To Roger Waters, Wherever You Are, from 1973’s As He Stands

I still can’t believe you got little else out of electronic music in the 1970s. Not even Kraftwerk?

RG: No. [laughs] Kraftwerk – they were most active 20, 30 years ago, weren’t they, but I’d always been disappointed in them. Disappointed in the form, more than anything, in the shape of the work itself. And I certainly get disappointed in most system music, or minimalism. To me, it’s just clever patterns. I was doing clever patterns forty years ago! It’s not enough. If someone could take electronics and harness Wagner instead – he’s fantastic for shape, the opening part two of Ring Cycle is just one note on bass, and he milks it until you’re nearly off the edge, driven berserk. To me, that’s art. Anything going to hit me now, got to be better than that. Or I enjoy the times I sit in the garden, in early summer, listening to the blackbirds and thrushes.

My favourite part of your record is called ‘Radio Fume’, where you sample lots of voices of DJs from Radio 3, then weathermen, shifting clouds… how did you do that?

RG: That’s the one where I pitched the voices like instruments, making the normally po-faced announcers cheery-sounding! It took all kinds of fiddling. To make these musical arguments in the introductions, this sense of people stuttering to go forward – to the second to last section, which is a total rampage – then to the last track, Home Jimmy. That was played by Stuart Maconie and I was chuffed. But it’s an odd one to explain. Everything I’ve ever done is odd! It’s like making a moving cartoons – imagine Disney’s Fantasia, the energy expended in doing the backroom work, rather than the work itself.

What would your dream outcome to the record be?

RG: If it will or might catch on a bit more, it could be done live. It wouldn’t take much to do it for augmented orchestra, and soloists, which might include four weathercasters. [sighs and laughs] God, that would be brilliant, wouldn’t it?

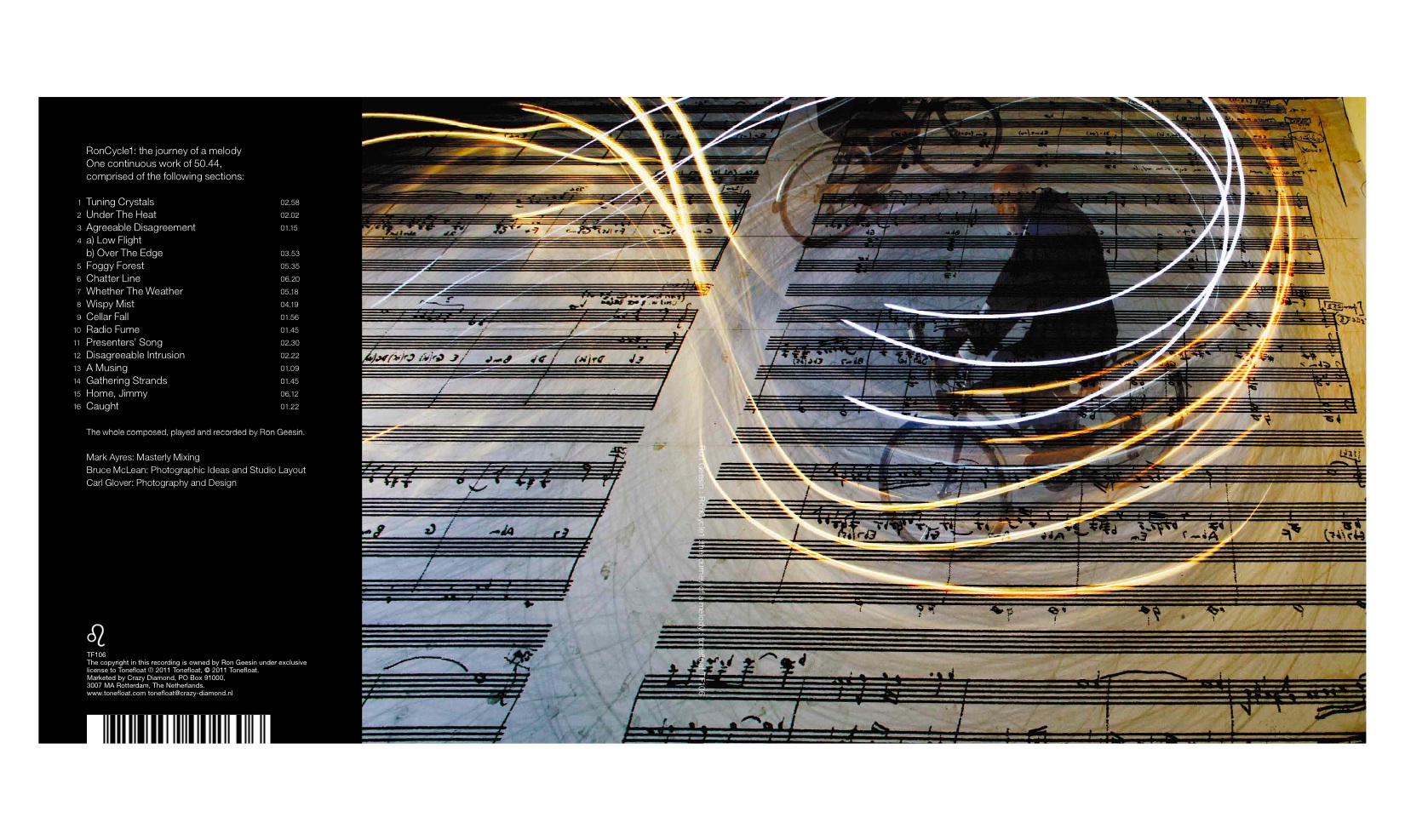

Roncycle 1: Journey Of A Melody is out now on Tonefloat Records