At times it’s a story that almost beggars belief. Searching For Sugar Man, if you’ve not seen it already, is a documentary about Sixto Diaz Rodriguez, the 70-year-old singer-songwriter from Detroit who released two glorious, largely unheard albums some four decades ago, then promptly vanished without trace. Various grisly rumours about his unfortunate life – murder, suicide, jail time – began to circulate in the intervening years. Meanwhile his records had become huge in different corners of the world. Not least in South Africa, where his baroque-folk protest songs had become beacons of hope amongst anti-Apartheid campaigners.

A pair of Rodriguez fans-turned-amateur-sleuths began sifting through the evidence to uncover the truth of what had happened to this mystic hero of the counterculture. Finally, in 1997, they found it. Rodriguez was alive and well and still making a modest living in Detroit. Then the tale took on a whole new twist.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Searching For Sugar Man is fast becoming the feelgood hit of the summer… well, outside of the multiplexes anyway. “It was the best story I’d ever heard in my life,” explains the film’s director Malik Bendjelloul, who first heard about Rodriguez in 2006, after meeting Stephen Segerman, one of the aforementioned amateur Sherlocks, in Cape Town. “Rodriguez is one the greatest artists you’ve never heard of. But then there’s also this thriller built into the movie, in that you have these detectives trying to figure out what happened to him – deciphering lyrics and trying to find out the truth behind stories that he’d died. Then we have the third part of the story, where his situation suddenly gets better. Here’s a man who’d been living as a construction worker for 30 years, not knowing that on the other side of the world he’s a superstar. And when he comes to realise that, it’s like The Truman Show or something. It’s like a true fairytale, with a kind of Sleeping Beauty quality. You’re almost crying when you think about it. It’s a beautiful, beautiful thing.”

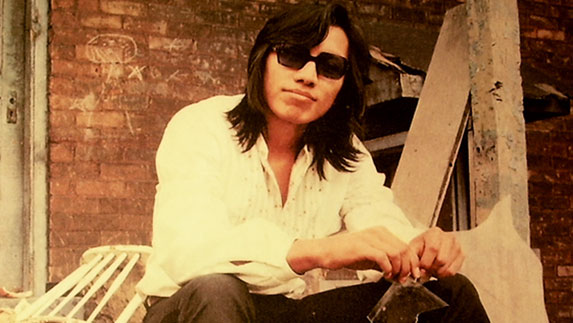

To grasp the scope of his story requires a jump in time. It’s April 1967 and Rodriguez, the 24-year-old son of Mexican immigrants, is playing small club gigs on the underground Detroit scene. Admired by local impresario Harry Balk, who signs him to his struggling Impact Records label, he’s introduced to Motown session guitarist Dennis Coffey and his production partner Mike Theodore, who oversee a debut single, ‘I’ll Slip Away’. It’s a spectacular flop and Impact soon folds completely.

Sometime later, Theodore and Coffey come across Rodriguez again. Much taken with his new compositions – and despite his somewhat bizarre habit of playing with his back turned to the audience – they introduce him to Clarence Avant, for whose Hollywood-based Sussex Records they’ve just signed on as A&R men and staff producers.

Recorded in late 1969 and issued in March 1970, Cold Fact – with Coffey on guitar, Theodore on keyboards and a crack rhythm section in Funk Brothers Bob Babbitt and Andrew Smith – became Rodriguez’ first album. It was a record full of oblique street poetry, insidious hooks and trenchant lyrics about inner-city blight and everyday struggle, made all the more affecting by bubbling grooves and Rodriguez’ almost casually fly-blown voice. A place where the tart polemics of Dylan met the languid otherness of Arthur Lee’s Love.

Alongside his signature tune, ‘Sugar Man’, there were songs like ‘Crucify Your Mind’ and ‘The Establishment Blues’. “It was a time of Kent State, the Zapruder film, Mai Lai and political assassinations,” explains Rodriguez today. “And in South Africa there was Apartheid. That was the backdrop for all the stuff that was going on. At that time, all of us were wondering what was coming down. I didn’t hang out with John Sinclair or the MC5 in Detroit, but I did get to know them later. John Sinclair was the guy who, for two joints, got two years. He’s one of the icons, one of the victims, of that era. If you grew up in Michigan and got busted for weed, you’d do time. I’ll tell you right now that it’s the same today. That stuff isn’t over. So that’s how I started writing songs. ‘Sugar Man’ is descriptive: ‘Future hugs, stay off drugs.’ I’m for the decriminalisation of weed, but I’m not trying to get anybody high. ‘Sugar Man’ is more like a plea.”

But Cold Fact stiffed. Probably not helped by a promo trip to LA, where Rodriguez played to a bunch of key industry insiders at the Ash Grove, his back resolutely turned to the crowd. Though, as he’s keen to point out now, it was more through habit than any intentional snub or aloof outsider statement: “The clubs I played in had always been really small. And if you tune your amp the normal way, you’re going to get feedback. So it was more to do with the sound rather than being afraid of looking at people directly. But yes, I did that. It wasn’t an insult to the audience, I just wanted to get the sound right.”

But there were other factors that contributed to the album’s swift demise. “A lot of the radio stations wouldn’t touch me, because of the nature of the songs. I would never get played in the Bible Belt, for instance. But I wasn’t trying to be controversial, it was just the way people spoke. Did I have dreams of being a big star? Yeah, I had hopes to make it. We all do, but in music there are no guarantees. You do it out of a sense of love for what you do.”

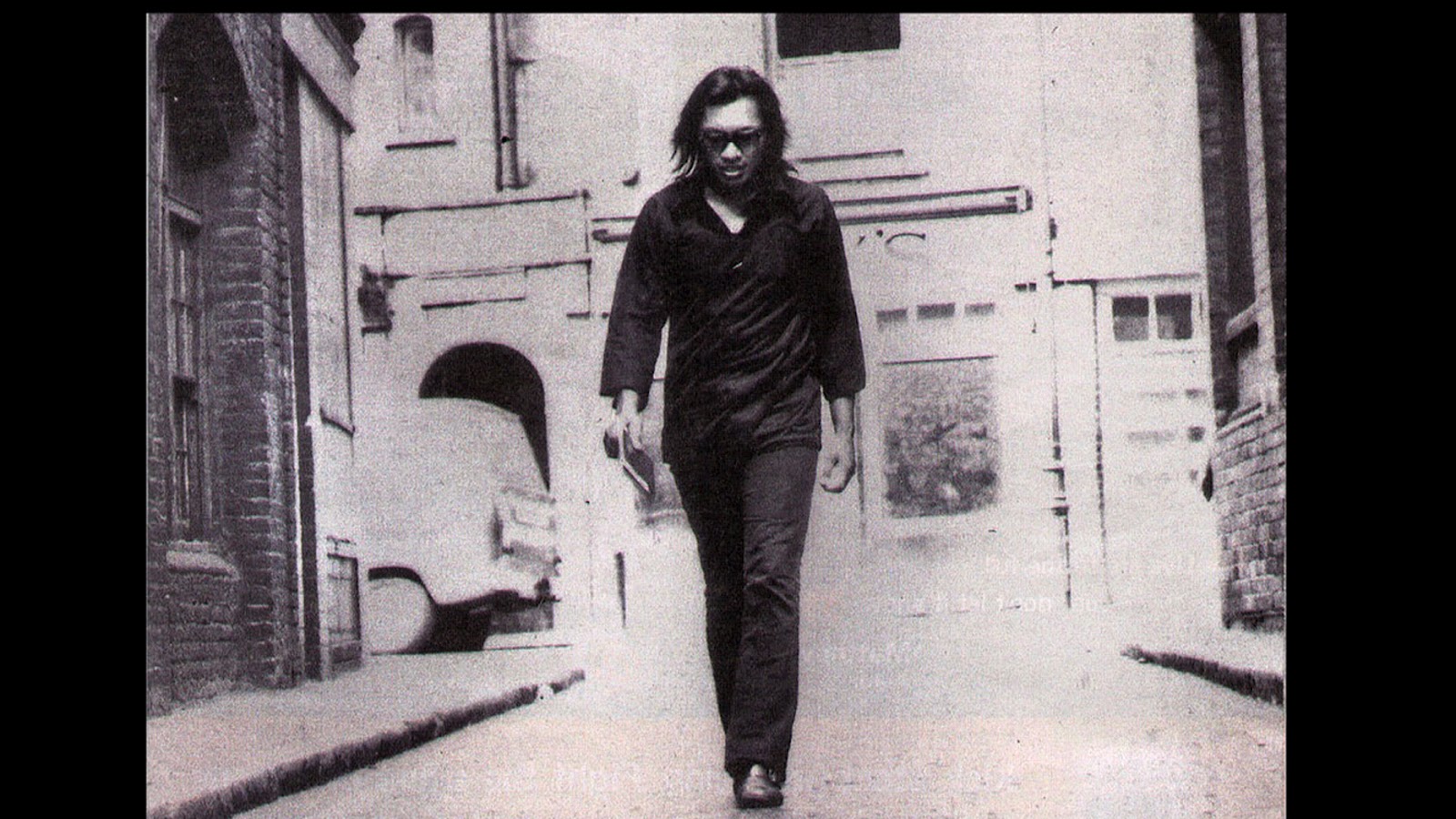

For 1971’s follow-up, Rodriguez was flown over to London, where he recorded Coming From Reality at Lansdowne Studios with Pretty Things producer Steve Rowland and a group of session men that included guitarist Chris Spedding. Yet the album, despite wondrous pieces like ‘To Whom It May Concern’, ‘Cause’ and ‘Climb Up On My Music’, sold even less than Cold Fact. It was enough to make him give up. “The label went bankrupt so everyone pretty much scattered,” he recalls. Soon after, he dipped from view. “If people are not showing at the gigs, it’s difficult and all very real. It was case of hey man, I can’t get something happenin’. I think a lot of us get disappointed like that."

He continues: "Nothing beats reality, so I decided to go back to work, though I never really left music. I took a BA in Philosophy, I became a social worker, I worked on a building site and got into politics. I always saw politics as a mechanism from where you can affect change. It took me ten years to get my four-year degree, then I ran for office. I actually ran for Mayor, for City Council, for State Representative in Michigan and I also ran for my life! You know what I mean? I didn’t have the political pull of the big guys, so you just do what you can do.”

But while Rodriguez was pursuing some kind of political career in Detroit, his albums had found their way to Australia and New Zealand via bootlegs and international licensing deals. Cold Fact first appeared in South Africa in 1971, where it became essential listening amongst the white male population of the army during the guerrilla border wars. When they returned home with their Rodriguez tapes, his music was swiftly adopted by white liberals in the ongoing fight against Apartheid. “They all dug it,” he reasons. “I think all that politics was questionable and my songs, being as they were, were reflecting what was happening. Y’know, why are people doing this stuff? It was chaotic. I mean, they killed a guy who opposed Apartheid in parliament over there. That was pretty shocking and that background was what we were playing against. There were soldiers who were musicians too and that’s what they were addressing. So they were there for me, all swapping cassettes of my music. That’s how I got spread around.”

In Australia, meanwhile, Cold Fact stayed on the album chart for over a year, eventually going five times platinum. It was enough to warrant a couple of tours there in 1979 and 1981, but after that Rodriguez seemed to go to ground completely. It was a disappearance that only served to magnify his mystique and deepen his legend. That’s when the stories began flying around.

“In South Africa it was as if The Beatles had been four faceless men without names,” says Bendjelloul. “Rodriguez was at least as famous there as The Rolling Stones and yet not even the record label knew where he was. When there’s no information, rumours start. One said that he was in jail, another that he had became blind, a third that he committed suicide on stage.” Others suggested he’d died of a heroin overdose or had set himself on fire during a live show. Or that, languishing in prison for murdering his wife, he had ended it all in his cell.

Years went by. Enter South African fan Stephen Segerman, who, having written the liner notes to the reissue of Coming From Reality, set about trying to find Rodriguez in 1996. Joining him on his quest were journalist Craig Bartholomew, then working on a story about their elusive charge, and another admirer, lawyer Brian Currin . What few leads they had only resulted in dead ends. Following the money was no good either. Despite his albums reaching multi-platinum status, they discovered that Rodriguez had not received a Rand in royalties.

Eventually, Bartholomew managed to track down Mike Theodore in Michigan. A tangled mess of phone calls, faxes and emails finally dislodged the truth. Rodriguez was still very much alive. By this time it was early 1998. “Stephen Segerman, Brian Currin and Craig Bartholomew were strangers, yet decided to find me,” marvels Rodriguez. “That was so crazy. They wanted to solve this mystery. They managed to get hold of my daughter in 1998. Segerman had a date in New York, then came over to Detroit to show me some CDs that had been selling. He was such a sweetheart. Then I started touring again. To suddenly be playing again was incredible.”

Rodriguez toured South Africa for the first time in March ’98, filling 5,000-capacity venues in all the major cities. It was only then that he began to understand his level of fame over there: “I thought I would be singing to Third World disgruntleds, but instead they were young, bright Afrikaners. And they seemed very sane! I couldn’t believe it when they started singing along to the words.” Adds Bendjelloul: “I think Rodriguez’ story fascinates people because it has so much to it. It’s about a man who lives a quite hard life and one day, when he’s well into his fifties, discovers that he’s a superstar in another country. When Rodriguez got to know about his South African fame he was working in manual labour, cleaning out houses to survive in the grim reality of downtown Detroit. But in the countries where people have heard about him, he’s not just a hip rock & roller, he’s a household name. I stopped random people in Cape Town streets and every second person knows exactly who Rodriguez is.”

A TV documentary of those shows – Dead Men Don’t Tour: Rodriguez In South Africa – arrived soon after. And while Rodriguez remained largely an unknown quantity in the UK and US, the slow build was now on. Influential rapper Nas sampled Sugar Man on 2001’s Stillmatic, then DJ/producer David Holmes featured the song on mix album Come Get It I Got It. In 2003, Holmes went one stage further, enlisting Rodriguez himself to re-record Sugar Man with a 30-piece orchestra for David Holmes Presents The Free Association.

But it wasn’t until discerning Seattle label Light In The Attic reissued Cold Fact in 2008, and Coming From Reality the following year, that Rodriguez’ legacy began to finally spread on a wider scale. It was enough for him to play the UK and Europe for the first time in the spring of 2009, where he was greeted like some long lost treasure.

It provided Bendjelloul, already in the midst of filming Searching For Sugar Man, with a readymade narrative arc. “It’s one of the strangest versions of the American Dream there ever was,” says the director, who admits to hearing Rodriguez’ music only after hearing his extraordinary tale. “There was a little trepidation, because I was so much in love with the story and didn’t want to lose the momentum by being disappointed when I heard the music. But then I heard the music and thought: ‘Jesus Christ!’ They talked about him in South Africa and Australia as being in the pantheon of rock gods, together with Dylan, Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones. And your immediate reaction is that of course it couldn’t be on that level. But I think it really is. Nick Drake didn’t get any attention when he was alive, then he was rediscovered years later. Why? Because the music was that good. So it makes sense that Rodriguez’ records are now everywhere. It’s accessible music on a really high level. He seemed much more than just a talent, he was a seer. He had this mythology around him. And when I eventually met him he still kept that mythology. The strange thing was that his experience hadn’t made him bitter. He studied philosophy, so maybe that’s helped give him a different perspective on things. There are different definitions of success and what life should be and what to strive for. But it all added more to the enigma.”

Searching For Sugar Man was a huge hit at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, where it won the world documentary audience award and a special jury prize. The reaction since, in Bendjelloul’s words, has been “absolutely crazy. We’ve had standing ovations at over 100 cinemas in America and in over 20 countries. And this is for a man who’d never played to more than 300 people in America in his life.”

And so to the man himself. How is Rodriguez dealing with this wholesale, and wholly unexpected, spike in fame and popularity? “It’s like a whirlwind,” he laughs, “I can hardly believe it. We’re going to be doing Letterman, the Newport Folk Festival and dates in New York and elsewhere. It all feels wonderful, it’s a lot to take in. So far I’ve seen the film 35 times! Had I given up on ever making it? I think I probably had. Put it this way, I was too disappointed to be disappointed. But now we’ve been four times to South Africa and four times to Australia and I’m finally breaking into the American market. I get a lot of seasoned hippies and a lot of young bucks too. People come up to me after shows and tell me stories about their dads listening to me. It’s all so rewarding. Everyone’s a young blood to me, because I’m 70! I really am a very fortunate man.”

Searching For Sugar Man, the original motion picture soundtrack is available now through Sony Legacy Recordings