Robert Sandall, Q, May 1989

There are, Robert Smith feels, two quite distinct and separate Robert Smiths. One is meticulous, fastidious even, firmly in control of everything he and The Cure do. The other is all over the place: a binger, a self-destructive follower of the path of excess. A man who, I can’t help noticing, has allowed himself to be trussed up, suspended from the ceiling of a South London warehouse and then lowered repeatedly into a large black furry orifice — "a spider’s mouth" apparently — full of some sticky gunk that looks and smells like Airfix glue. Perhaps the fumes are getting to him, because this Robert Smith is clearly having difficulty "lip-synching" through the final sequence of what must rank as one of the most dangerous and undignified video-shoots since the Pepsi-Cola commercial that set fire to Michael Jackson.

Everybody on the set, bar the figure dangling from the winch, seems to find this scenario rather droll. Especially amused is an untidy, gangly looking bloke huddled over a small green monitor screen which he scans with eccentrically swivelling Marty Feldman eyes. He waves his arms and shouts about "the baby", but he is not mad, he is the director, Tim Pope, instructing the cameraman. He has been doing this for the past two days. By the time he has finished tonight The Cure will be £80,000 lighter and a "promo video" for their new single ‘Lullaby’ will be in the can.

Pope has devised and directed every film and video The Cure have made since 1981. The first commission — to film the band in concert — filled him with dread. "I just thought, They don’t do anything." But a relationship has developed. Smith lets Pope impose, some might say inflict, whatever storyline he chooses: The Cure were crammed into a wardrobe for ‘In Between Days’; today Smith is being tormented and eventually eaten by a giant spider. And it is these fantastical creations that have largely made Pope’s oddball reputation. Not only does he now direct videos for other groups like Talk Talk and The The, he also directed that mysterious "comedy" series The Groovy Fellas for Channel 4. And he makes commercials in America.

But The Cure is his first love. "There’s like this private joke between me an’ Smiffy," Pope explains in his excitedly "street" tones. "It’s like I’m always torturin’ ‘im an’ ‘e ‘ates me! But The Cure is the ultimate band for a filmmaker to work with because old Smiffy really understands the camera. His songs are so cinematic. I mean on one level there’s this stupidity and humour, right, but beneath that there are all Smiffy’s psychological obsessions and claustrophobia." Pope has discovered in ‘Lullaby’ an allegory of Robert Smith’s druggy past.

The video shoot’s lunch break (3.30-4.30pm, "Smiffy" is a nocturnal animal) is over. Technicians, clapperboard holders and all the other under-employed accessories to the filmmaking process drift back to their positions. But not Pope. He has plenty more to say. About The Cure’s unusual sound textures — very cinematic they are too, apparently. About the special "video mixes" Smith arranges. About the coded in-jokes that silently pass between them, and about their telepathic understanding: both had independently visualised ‘Lullaby’, the first single off The Cure’s new album, in terms of certain scenes and characters from David Lynch’s futuristic cult horror movie Eraserhead. "Most videos, especially in America, right, it’s like stick a light behind ’em, make ’em suck in their cheeks, wobble their tits, dance or whatever, chuck in some fuckin’ smoke or a strobe and that’s it! But they’re getting a feature film production ‘ere."

He gestures at the furry black thing, at the makeshift shed-like contraptions in which the rest of ‘Lullaby’ has been filmed, and at what might be four more members of The Cure, looking as casual as a rock band can when clad in raggedy Napoleonic military costume, an inch or two of white makeup and a substantial garnish of the gluey, cobwebby gunk.

Meanwhile Smith, his mouth now a gash of crimson lipstick, his hair an artfully tangled mess, has returned from another spell with the Japanese make-up girl. He is crouched studying a series of cartoon drawings propped against the wall. This is the storyboard, a 25-frame breakdown of the entire video, commonly used in feature filmmaking but seldom seen in the fourth division of cinematography to which the promo video belongs. Smith beckons to Pope: "That’s the other thing about old Smiffy," he says with a respectful cackle, "he’s such a meticulous bastard."

Sadly, this meticulousness in no way applies to his timekeeping where interviews are concerned. Two appointments are made then abruptly postponed. In The Cure’s management office in Marylebone there is much lofty talk of "the problems juggling Robert’s schedule" while, at the third attempt, our two o’clock meeting reschedules itself for half past three. Finally Smith ghosts in, mumbling something about a taxi and trailing his bass player Simon Gallup. His lips bear the traces of smudged lipstick. His hair is in the same rumpled crow’s nest condition as it was during the video shoot. He explains, in his Sarf London drawl, that Gallup is only here "to make sure I don’t tell any lies".

There is something about such a combined display of diffidence, archness and unpunctuality which makes you quite want to thump this otherworldly rock’n’roll personage, Robert Smith. And it’s an impulse that is steadily compounded by the fey, faltering manner of his speech: head drooping into his hands, every other word dissolving into a sigh, "um" or "I dunno". This man is almost too much like a cue for one of his own angst-ridden tunes to be true.

"I never think of myself as a rock star. I never even think I’m in a group unless I’m doing an interview," he alleges, sotto voce, lowering his hairdo for my inspection and tugging distractedly at his face with his hands. "I still shop at the same cack shop. I live in the same basement fiat in Maida Vale. Drive the same old jeep. I spend a lot of time doing pointless things like, um…keeping all our artwork going but I never even pick a guitar up nowadays because…. I dunno…. I never get any better. I would prefer to read than play the guitar. And I’ll read anything because I’m … cursed. I have to finish a book once I’ve started it, um….which means that I read a lot of dross." He is currently reading something by an obscure novelist of the 1940s called Denton Welsh. Welsh, he points out, died after getting knocked off his bicycle. Cue for another song, perhaps.

It is difficult, though, to reconcile this dreamy, dozy melancholic with the virtually single-handed achievement of such a consistently rising graph of international success. After 11 years and eight studio, one live and three compilation LPs, The Cure have now sold around eight million albums worldwide. A quarter of those went on their last, the double album Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me which "did" a million in the States. This exponential increase is supported by sales of their back catalogue; new product helps to sell old. The Cure are huge — approaching Michael Jackson status — in France where they appear (on one memorable occasion, all wearing dresses) on Wogan-esque TV shows. But there is no market in the world in which The Cure don’t enjoy a respectable presence. They are signed to Polydor through their own label Fiction on a royalty rate over 20 per cent, roughly double what most artists get. Their tours are internationally renowned among promoters for their leisurely schedules and picturesque routes If anyone is ahead in the rock game it is Robert Smith.

And yet here he is, studiedly glum, describing his depressions, explaining away the success.

"I do have, um, this very strange split personality. I can reach a point where I am fanatically ordered. And at the other extreme I let everything go to pieces. Put myself at physical risk. Like when we were in Paris I climbed round the outside of the hotel we were in to get into one of the other rooms. On the second floor. And being in America changes my personality completely. It makes me monstrous. As loud and obnoxious as a lot of the people you meet over there are." He declines to give examples. "I can’t stand America. I mean the playing’s all right, but the nutters there are worse than anywhere in the world."

From this, and more like it, it emerges that The Cure do act as a magnet for unstable types and that Smith himself is partly motivated by a morbid fascination with the fragility of mental health, particularly his own. While filming a video for ‘Charlotte Sometimes’ in 1981 at a disused lunatic asylum in Virginia Water, Smith found, and was captivated by, drawings by old inmates. Anxious to register a sympathetic vote, The Cure began playing benefit concerts for MENCAP (the society for the mentally handicapped), and an element of therapy crept into their performances. In particular, Smith tired of the guitar and developed a faintly old-fashioned interest in the trance-inducing possibilities of singing. He loses himself, he claims, behind a microphone on stage; Gallup confirms that their leader frequently goes spiritually AWOL during performances, particularly in countries where English is not the first language. In South America or Japan, Smith sings anything that comes into his head.

Indeed it was a by-product of such onstage behaviour which provided Smith with one of his visual trademarks, the smudged lipstick.

"I started wearing it because it made me feel confident and more attractive. I’m completely featureless without it. But on stage I always used to lean my mouth on the mike and shut my eyes so I wouldn’t have to see the people. And at the end I’d come off with lipstick smeared all over my face, so I thought I might as well go on with it like that and make it look intentional." Keeping a watchful, opportunistic eye on his weirder manifestations is clearly an important part of being this paradox, Robert Smith.

But weird he is, Tim Pope firmly believes. The director has, among other things, detected Smith’s bizarre obsession with mouths. "I do find mouths fascinating and kind of repulsive. They’re sort of like a … gaping wound in people! They can be really horrible. It’s such intimate part of your body and yet it’s a multi-purpose opening, used for shovelling food and pouring drink into. I find myself sometimes with people I don’t know just staring into their mouths…."

There is of course, one simple and obvious explanation for his preoccupation with themes of a somewhat wacko nature: too many drugs. These, one can state with some precision, entered his life at the time he joined Siouxsie and the Banshees as a part-time guitarist in 1979. The Banshees’ regular guitarist John McKay jumped ship in Aberdeen on the eve of a national tour and Smith, already in place as support act with The Cure, stepped in, playing two sets a night. The association was to last for four years. "It allowed me to go mad for a period of time. With the Banshees I had no responsibilities. I just had to turn up and play the guitar. Badly. Just used to turn all the effects pedals full on, which is your basic Banshees sound. And Severin and I became good friends although, um, we were never very good for each other. Our friendship was based entirely on altered states. Whenever we went out together I would never get home until the next day. Mary (his wife) hated it. I’ve never felt so bad in all my life as when I was with the Banshees. I reached a point in 1983 of total collapse."

It was perhaps the only point at which "the madness" eluded his control. "I really wanted to push myself to the limit. I’ve always been a very healthy person but I still find now that all that excess has undermined my constitution." He laments the loss of his footballing prowess and, more generally, his figure. Not for nothing has he acquired the nickname "Fat Bob".

But the damage he inflicted upon himself was no more severe at the time than that he visited upon The Cure. After the epic gloom of the Pornography album and tour, during which Smith put lipstick round his eyes "to look like blood", Gallup left (for 18 months after a drunken row with Smith). For the next two albums, Japanese Whispers and The Top, the band were reduced to a duo — Smith and drummer Lol Tolhurst. Meanwhile a recording project with Severin, The Glove, took Smith to the threshold of permanent Bansheedom: he wanted to sing as well as play and was only talked out of it by his genial Australian manager Chris Parry, who realised that Smith’s plaintive wail was all that still separated the two groups. He also knew that Polydor were secretly encouraging a merger they hoped would result in the transformation of two of their medium-sized acts into one big one.

Smith’s response to all this was, he admits, "very muddled. Everyone around the Banshees is always telling them the Banshees is it, the only thing, which is very unhealthy I think. And if I’m with The Cure I couldn’t accept that. The Banshees are really stagnating now. I wish they’d do something better."

Despite being in possession of a manner which, if it were a bit more lively might be termed "laid-back", Smith is a man of strong, not to say fierce, musical prejudices — and particularly where those acts you might describe as "the competition" are concerned. He finds goth music "incredibly dull and monotonous. A dirge really." He singles out Michael Clark, the ballet dancer, and Clark’s friends The Fall for a special mention as "pretentious wankers". And he reserves his most impassioned speech for a critical assessment of Morrissey. "He’s a precious, miserable bastard. He’s all the things people think I am. Morrissey sings the same song every time he opens his mouth. At least I’ve got two songs, ‘The Love Cats’ and ‘Faith’. If only people knew how easy it is to be in groups like The Smiths . . ."

He takes a more sanguine view of his own work. "Not wanting to sound big-headed or anything," he says, and not for the first time, "I’ve been in at least five different groups since I’ve been in The Cure, I’ve been everything — punk, goth, psychedelic, pop. It was really great showing that The Cure could make pop singles. Now we’ve drifted back to that sort of atmospheric music we did on Faith. But the thing about The Cure is we exist in isolation. We’re not in competition with anyone. One day I suppose we’ll stop. But we’ll never be replaced." As this proposal illustrates, the I/We distinction is one that Smith, in common with the Prime Minister, has some difficulty with. In business terms he treats the band generously: the songs are unmistakably his, yet everybody who plays on a Cure album usually ends up with songwriting credits and performance "points" — a royalty percentage — rather than a wage or a flat fee. The group ethic is staunchly upheld. But on the other hand, the hiring and firing which has turned The Cure into a fluctuating aggregate of between two and six persons across half a dozen line-ups are not a matter for democratic discussion. Take, for example, the case of Tolhurst: drummer turned keyboardist, Smith’s only constant companion in The Cure up to and including the recording of Disintegration; currently unemployed.

"I just told him that I didn’t want him around anymore. He’d become a fixture, only appearing at meal times and totally out of his head. Lol’s never had any musical input and he’s the only one of us who hasn’t been able to pull back from the excesses of being in the group. His function has always been as a sort of victim, and by the end all the jokes, the bitterness, the conversation everything was focusing on him rather than the music. Lol knows why he’s not in the video and why he isn’t going on tour this summer. When you’re a six-piece you’ve got to have some dedication or it just ends up like a football team."

Dedicated to the point of daftness, The Cure do work quite hard at maintaining what Smith describes as "a Cure world". Initiation into this esoteric community chiefly involves being rechristened by Smith himself: Tim Pope is "Pap", The Cure’s regular producer Dave Allen is "Dirk", manager Chris Parry is "Bill". Robert’s wife Mary is "May". Everybody on the payroll except Simon Gallup is somebody else, "because I feel more comfortable like that. It’s more friendly, it’s a link beyond civility. Besides," he drifts into his fey, "meaningful" mode, "people are only given these names when it’s obvious they need them”. His own alternative handle, awarded by former bassist Matthieu Hartley, is Robin, short for Christopher Robin. A good choice that, since in Smith’s case the child has clearly been father to the man.

His wife Mary has been his regular consort since he was 15 (he’s now 29). Brought up as a Roman Catholic in Crawley and educated in local Catholic schools, Smith could still be seen as recently as 1980 attending Sunday services in The Friary, Crawley, with Mary. Only the blue ribbons in his spiked hair hinted at the nature of his day job. Smith now draws a veil over his Catholic past, but a heavy atmosphere of sepulchral religiosity still lingers about much of The Cure’s music.

And so do some of Smith’s other adolescent interests: the depressive poetry of singer-songwriter Nick Drake (who committed suicide in 1974), the playful cosmetic experiments of the glam-rockers — David Bowie in his Ziggy Stardust period, Roxy Music and, later on, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band. (Smith followed the group around the South of England, particularly struck, he recalls, by guitarist Zai Cleminson). Also still going strong today is Smith’s curious affinity for French literature of the "A" level set text variety, first detectable on The Cure’s debut single ‘Killing An Arab’ in 1978. Seldom has existentialism — the song describes a scene in Camus’ novel L’Étranger — sounded so perky.

"I’m very aware of the heritage of the absurd," he improvises, intellectually. "I still have that sense that everything is really stupid. That line of thought still stirs me, or doesn’t as the case may be. Playing in a group is absurd. All that self-aggrandisement (he pronounces it French-style). And I’m still fascinated by funerals, by that thing of Meursault (hero of L’Étranger) being the outsider at his mother’s funeral…" A song on the last album, ‘How Beautiful You Are’, was inspired by a short story by the French poet Baudelaire. Small wonder that the French have written learned articles locating the band within the French romantic tradition.

The crafting of this ragbag of eccentric materials into one of the more durably popular British rock routine’s of recent years — a "Pink Floyd for the 1980s", it has been suggested — has not, according to manager Chris Parry, involved any clever marketing ploys. Parry originally signed the band when he was still an A&R person at Polydor and has looked after them ever since, but he is far from a Svengali manager.

"Robert just does what he wants. He lives in his own bloody world basically." Parry has intervened, he says, twice. First to rescue the Pornography tour in 1982. "I knew that would be a tough album to promote, so I just spent a lot of time making sure we had a really good stage production. I knew that a few lights blinking on and off wouldn’t be enough for that one. I just said, ‘Look, this is not a good way to go out’." Parry’s second cautionary gesture was made after The Top album in 1984, when Smith’s drink and drug problem ("everything but smack") was at its height. "That album was a struggle. Robert looked terrible, puffy-faced, eyes bleary, sores on his lips. He was always listless. I was worried that he was going to have a heart attack, and I told him after we’d finished, driving back home in the car, ‘You know there are a finite number of records we can make in this way’."

Smith took note on both counts. The Cure are now fashionably drug-free and the only misdemeanour which Smith will own up to is "getting drunk on Sunday night". And their stage shows are now carefully prepared. Since 1985 it has been their practice to send one of their team out into the audience before a concert with a video camera. Fans are asked which songs they would most like to hear and the band watches these responses in the dressing room, rejigging the set as necessary. This extraordinary bid to preserve good customer relations tends to support Parry’s other main observation about Smith. "He does have this very highly developed sense of audience. Like all good artists, he lives in other people’s perceptions."

In my perception, Robert Smith seems genuinely obsessed and infuriatingly posed in almost equal measure, an ambiguity which must perhaps inevitably cling to somebody who chooses to play so hard at being "sensitive" in the rather insensitive format of a big arena rock band.

"I still feel the same as when we started during the punk thing," he declares brattishly. "What we do is an alternative — not to Bros but to Elton John and Chris Rea and all those fucking old bastards who were there then and still are. It’s so embarrassing to see these old people doddering about, like Dire Straits. They’re hideous. I’m sure they must be different people posing in latex masks."

This piece of rock’n’roll bluster despatched, Smith comes over all pale and interesting, enthusing about the superiority of reading over other forms of entertainment, complimenting Mozart and other old, nay dead, composers ("I only listen to classical music nowadays"), offering an exquisitely effete account of his reasons for being in such an unclassical combo himself. "It wasn’t for the drugs or the women, it was just the best way to avoid getting up in the morning."

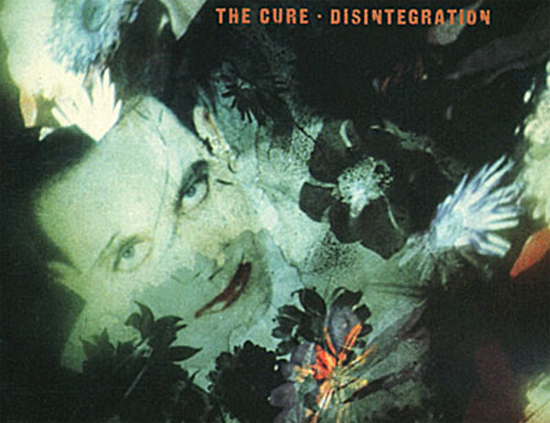

Entropy, thy name is Smith. And is Disintegration, then, The Last Cure Album? "It would be ridiculous to feel any other way about it," he retorts with practised weariness. "It’s really emotionally exhausting making an album. I usually end up crying in the studio, which is a problem, because if you get emotional like that it just sounds as if you’re singing badly. Yeah, I still haven’t got over making this one yet…"

Robert Smith’s voice is getting fainter. He is starting to sound like one of his songs again. "Every record we do is the last one…"

© Robert Sandall, 1989

Rock’s Backpages is an archive of the best music writing and criticism of the past 50 years. Sign up here for the weekly RBP newsletter, listing all new additions to the library