The Boy Who Would Fly: Michael Jackson

Barney Hoskyns, NME, September 1983

I’ve been feeling strange about Michael Jackson since I was 11 years old. I remember lying in bed with a tranny the size of a large matchbox pressed to my ear, entranced and slightly embarrassed by the choirboy purity of ‘l’ll Be There’. I remember thinking, gosh, he’s only six months older than me; I wonder what he’d be like if he came over, you know, watched TV and played football. Now I can guess.

I loved the Jackson Five records but I never teenybopped to them. I was too busy watching Michael jump around the stage while Jackie and Tito loomed over him like giants, their Afros apparently growing bigger by the minute. The cover version of Sly’s ‘Stand’ said it all: "there’s a midget standing tall, and the giant beside him about to fall." I was green with envy.

It was when I bought ‘I Want You Back’ that the Motown sound first knocked me sideways. Like John Lennon When he first heard the booming organ lead-in to ‘Stop! In The Name Of Love’, I couldn’t believe how loud it was. From the piano cascade into the crashing cymbal and guitar, through the bass tearing the bottom out of my speakers, I was literally thrown back from the turntable. Berry Gordy could call it soulbubblegum for all I cared, I hadn’t heard such crazed music in my life. In the treble register it was anarchy – frantic strings, rippling guitars, hi-hats, tambourines – but through it came this tiny tantrum, a kindergarten whirlwind, belting and swaggering out of swaddling clothes. It had all the power and determination of a miniature James Brown.

And it was all I neeeeeed(ed). Thirteen years on and still I wanna be startin’ something. Michael Jackson is singing "you’re a vegetable", only it sounds like "nashty boy" or "nashty girl".

He’s charging these words with the bitterest twists, bending and dragging them, winding vowels round his throat, spitting syllables like darts of poison. The drum machine’s programmed for eternity; like a piston, it goes on hissing and revolving, turning and driving, too high to get over, too low to get under. You’re carried, you can’t escape, you’re ripped by the voice’s current. And it won’t stop till you’ve got enough.

How does Michael cut so deep? Why does he do me that way?

Sometimes I wonder how great Michael Jackson really is, and how much of his "magic" derives purely from the spell of fame. He is, after all, the biggest star on earth. There’s no-one who can command his fee, precious few who can pay it. The promoters of this year’s US festival offered over $1 million. The response was simple: "You’re not even close."

His fame fascinates because it is total. Seemingly withdrawn from it, in fact it cocoons him. Like Howard Hughes, he doesn’t have a public relationship with fame but abstractly embodies it. So when he starts saying things that sound completely mad, like "if I could, I would sleep onstage", he is simply stating a logical implication.

When one says that Michael lives in fantasy, one is not just referring to the fact that he thought ET was a real living creature, or that his favourite movie is Captains Courageous (would you believe one of its characters is a fisherman called Disko Troop?), or that he confides more in his pet llama and his mannequin collection than he does in his own family. One is saying that up on the stage, deep in the dark womb of the studio, Michael’s voice is a vehicle of fantasy, an instrument ceaselessly running circles round itself, tripping itself up, playing make-believe.

He can take the human voice as far out as Diamanda Galas. On the Jacksons Live album, there’s an extraordinary half-minute between ‘I’ll Be There’ and ‘Rock With You’ which perhaps conveys more of Michael Jackson than anything he’s ever done. Breaking free of accompaniment with the playful virtuosity of a saxophonist, he winds up ‘I’ll Be There’ with a series of piercingly sustained shrieks, cutting up each cry with a tiny ripple of chuckles. The audience goes predictably ape: reflex gratification. But for Michael, every breath, every laugh, every "hick!" is a link, a phrase, a segment of the flow. So engrossed is he by himself that his own responses to his voice are incorporated into the performance. "BE THEY AAARE!HICK! CAN YER FEEEL EEEEAAART! YIP!" Going up two octaves: "HEEEAH HEE HEE HEE! HEEEAH HEE HEE!" Down again. "AH DEE DADA DADA DADA DUNKA DUNKA DEE DADA DUNKA … I THINK I WANNA ROCK!"

It’s a voice which starts into every split spare second, stretching like rubber, filling cracks like water. It’s not warm or sensual or "black" but sharp, a squeezing of the throat’s aperture, a voice of pure technique. Detaching itself, it gets lost in free flight. Its narcissism is almost not human.

For two months, while preparing in Los Angeles for an interview that never happened, I couldn’t hear this voice without feeling that it was all there was to know about Michael Jackson, that in it he released everything which is otherwise denied him, all that must stay quiet. At a point of masturbatory orgasm, it can all but shut out the world. To try to engage it in conversation seemed absurd, dangerous.

There was a time when I wrote The Jacksons off. As for Michael, I felt sure that this puckish dynamo, part Frankie Lymon, part James Brown (with something, too of former 12-year-old genius little Stevie), would, like all child stars, crack, go mad or end, like Frankie himself, a penniless drug addict. Isn’t that how all pop’s fairy tales conclude?

But no, Michael fasted, stretched into an unnaturally elongated superfreak, a balletic stick insect, looked into the business, and when The Jacksons left Motown for Columbia in 1975, was lined up to star in a CBS biopic called – you guessed it – The Life Of Frankie Lymon.

In all fairness, before 1978 there was little evidence of any production or songwriting talent. Trapped at Tamla for six years, where the hacks of the self-styled "Corporation" became ever more predictable in their selection and treatment of the group’s material, they left Gordy’s fold in a blaze of controversy, stripped of their name, only to be cosseted for a further two non-albums by the hacks of Gamble and Huff in Philadelphia. Yet one song on The Jacksons (1976) bore a second listen. Tucked away at the end of side one, ‘Blues Away’ had a pleasant shape and substance that the rest of the record lacked hopelessly. The credit said Michael Jackson.

After Goin’ Places (1977), The Jacksons looked beat. The doowoppy strains of ‘Heaven Knows I Love You, Girl’ were quite unsuited to them. Motown had tried them on The Delfonics’ ‘Ready Or Not (Here I Come)’ back in 1970, but as Nelson George dryly remarked, "no-one ever accused them of being a great close harmony group". From ‘I Want You Back’ through ‘Mama’s Pearl’ to ‘Doctor My Eyes’, the Five have always been at their best with bubblegum. Popcorn love, you dig? (New Edition certainly do.) Philly just wasn’t their style. As for the orchestral disco funk of ‘Enjoy Yourself’, ‘Keep On Dancing’, et al, – a muted continuation from their last Motown album, Movin’ Violation – I’d say they were lucky to get hits from this period at all.

When the proof of talent finally came, you wondered why they’d bothered with anyone else, particularly producers as stylistically bankrupt as Gamble and Huff. Destiny (1978) wasn’t a great album but it had a sprinkling of great moments which one can review now as sketches towards the superb Triumph (1980). The ballads, for example, anticipate ‘Girlfriend’ and ‘Time Waits For No One’. ‘Things I Do For You’ points crudely to ‘Get On The Floor’ and ‘Everybody’. Singleswise, ‘Blame It On The Boogie’ was flatulent pulp but ‘Shake Your Body’ prefigured everything that would so gloriously burst open in ‘Lovely One’, ‘Don’t Stop’, and ‘Walk Right Now’. It’s wondrous flavour is due to the presence of ex-wonderlovers Nathan Watts(bass), Mike ‘Maniac’ Sembello (guitar), and Greg Phillinganes (keyboards), who has featured on Jackson output right up to Thriller. These guys do so much more than the half-asleep MFSB of the Philly albums.

On Destiny, the best is saved for last.’That’s What You Get (For Being Polite)’ was the first evidence that The Jacksons – in this case Michael and the (I suspect) very talented Randy – could write a great soul toon. Moreover, it seemed uncannily close to a self-portrait of Michael. The song is about a character called Jack (the ‘son’ castrated?):

Jack still sits alone

He lives in the world that is his own

He’s lost in thought of who to be

I wish to God that he would see

Just love, give him love…

The song ends:

Don’t you know he often cries about you

He cries about me

He cries about you, about me, about you

Don’t you know he’s scared?

Don’t you know don’t you know don’t you know…?

That’s what you get for being Michael Jackson.

In The Wiz(1978), Michael played the scarecrow who is looking for a brain, an irony not worth labouring here. The film’s musical director was none other than Quincy Jones, and a single from the soundtrack, the inoffensive ‘You Can’t Win’, was Michael’s first solo release since leaving Motown.

Obviously more important was the resulting partnership on Off The Wall, a record whose landmark stature need hardly be mentioned. By now it must have been purchased by every pop fan on earth and even as I write is probably being secretly exported to other galaxies. Of course, as an album it’s not great, but if the first time you heard ‘Don’t Stop (‘Till You Get Enough)’ doesn’t rate as almost the greatest moment of your life, you’re obviously some kind of vegetable.

Off The Wall is an oddly mixed bag – Carole Bayer-Sager here, Earth, Wind, & Fire there – yet it’s possible to see it both as culmination (in Gavin Martin’s words "the final summation of the great disco party") and as the inauguration of a new, softer funk for the 80s. Like EWF’s ‘Boogie Wonderland’, ‘Don’t Stop’ takes ”disco" into the outer cosmos, while the sublime Rod Temperton songs – ‘Rock With You’, ‘Off The Wall’ – look forward to the less frenzied black pop of today. Nothing has topped them. Born out of Heatwave (Temperton-written) and The Brothers Johnson (Jones-produced ),the initial trio of singles took the world completely by storm. Nobody had heard such draped, sweeping choruses before, nor been pummelled by brass like Jerry Hey’s Seawind Horns; never had a pop voice stretched so far. Off The Wall contains the most intricately times, fully textured, glossily sensual dance music ever made. It’s still a giant thrill.

If people hadn’t been so busy awaiting Off The Wall‘s successor, the next Jacksons album, Triumph (1980), might be more often lauded as the magnificent record it is. Rivalled in the exalted sphere of Superdisco by only Earth Wind & Fire’s I Am – by which it is more than a little influenced – Triumph is genius almost from start to finish: almost because as it happens its only weak points are the pompous opener ‘Can You Feel It’ and the closing so-so, Jermaine-ish ‘Wondering Who’. Everything else either melts or stings. The scope of the production, the authority of the arrangements, the sheer strength of sound, all are dazzling.

Above all, it’s the supposed "fillers" which really consolidate it as a complete album. ‘Your Ways’ and ‘Give It Up’ show how effortlessly The Jacksons can do their own EWF, their own Isleys, even their own Temperton. Of course Michael learnt a great deal from Quincy, but here he goes one step beyond. While nothing matches ‘Don’t Stop’ or ‘Rock With You’ (what could?), Triumph is finally, simply, a better record than Off The Wall.

‘Check Out This Feeling! ‘Everybody’ is a dramatic reconstruction of ‘Get On The floor’, ‘Lovely One’ is a radically exciting dance cut, while Randy’s and Jackie’s ‘Time Waits For No One’ is possible the most affecting ballad Michael’s ever been given. Finally, ‘Billie Jean’ Mark One ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ takes Maurice White on at his own game and knocks him out of the ring. Michael’s no Phillip Bailey, but Bailey couldn’t reach this pain.

Which finally brings me round to Thriller. May I ask what all the fuss was about? If Tavares release a duff platter, do people suddenly start preaching about "blandness", "complacency", and all the other cardinal California sins? Gimme a break.

Besides, is Thriller a bad record? Hardly, I’ll grant you that ‘Wanna Be Startin" was a tame successor to ‘Don’t Stop’ and yeah, ‘Baby Be Mine’ wasn’t such a hot ‘Rock With You.’ Oh alright, ‘Beat It’ stank, it was stupid and clumsy and every time the drums came on the radio I prayed it was ‘Let It Whip’. But heavens, Off The Wall had ‘Get On The Floor’ and ‘Falling In Love’, and to be honest never reckoned too much on ‘Working Day And Night’, so what did you expect, perfection?

What did we get? First, anything that brings Eddie Van Halen and ‘Soul Makossa’ under one roof is in my book pretty cool. More seriously, ‘Billie Jean’ was great. I know you all heard it at least 3,482 times, but really, that hissing electro hi-hat, that beat, the bass, Jerry Hey’s mad string arrangement… I mean, do we have a fantasmatically supreme record here? Alright!

Beyond that? Well, there’s my own fave, the beautiful Toto creation ‘Human Nature’ – and anyone who knocks Toto In my presence may politely F. off; I suggested they examine ‘Crush On You’ or ‘I’d Rather Be Gone’ from Finis Henderson’s album for corroboration of their discreet brilliance. Apropos of which, the group is co-producing the next Jacksons album, due in the spring. (One of the songs is apparently called ‘The Hurt’.) I’m also quite partial to ‘P.Y.T.’ due to its extravagantly thick moog bass. This leaves the only disappointment, which is Rod Temperton, who signally falls to deliver a killer. Even the title cut, despite its ‘Boogie Nights’ riff and blazing brass, is as hacked out as ‘Turn On The Action’ on Quincy’s The Dude.

This is not, however, enough to stop Thriller standing up as one of the strongest albums of the last ten months.

Some people seem to think that because he’s not big, butch, and badass, Michael Jackson is some kind of saint, a child lost in time. Perhaps it’s true. Certainly his peculiar appeal has something to do with his raceless and asexual physique. The epicene translucence of his face is almost otherworldly. It reminds me of only one other black artist, the young Miles Davis.

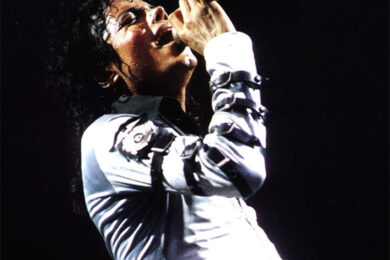

Michael goes so far as to compare himself to a haemophiliac, betraying an instant paradox; for if he is a haemophiliac, he’s one who only feels safe surrounded by sharp edges. In other words, he feels strange around people but not in front of crowds. As Vince Aletti put it, he has "a compulsion to entertain". It is only before crowds that he can "lose himself", touch that innocence where magic reigns.

Sometimes the articulacy of this shy, paranoid, tongue-tied idol is positively unnerving. He hates to describe himself as an actor because "it should be more than that. It should be more like a believer… Sometimes you get to a note, and that note will touch the whole audience. What they’re throwing out at you, you’re grabbing. You hold it, you touch it, and you whip it back – it’s like a Frisbee."

Michael is alone amongst superstars in consistently hinting at misery – at the absence inside. How can he live in himself when he is everywhere outside, when at the age of 12 he was watching cartoons of himself on TV? The world is plastered with him, he is a thousand billboards. And the tragic truth seems ancient, that only onstage can he get back inside.

All this is rather wonderfully illuminated by the German author Kleist in his 1810 essay On The Marionette Theatre. In the essay, a dancer has become fascinated by marionettes, or puppets. He believes that because they are not conscious, and are thus free of affectation, they are more graceful than we are – they have "a more natural arrangement of the centres of gravity". Scorning the vanity of modern dancers, whose souls often appear to reside on their elbows, he says:

"Misconceptions like this are unavoidable, now that we’ve eaten of the Tree of Knowledge. But Paradise is locked and bolted, and the cherubim stands behind us. We have to go on and make the journey round the world, to see if it is perhaps open at the back."

Hinging on the third chapter of Genesis, in which Adam and Eve eat from the Tree and become conscious of their nudity and their difference, the essay makes clear that we cannot simply forget our fall and regain Innocence. If life is the graceless search for grace, knowledge must "go through an infinity" to arrive back at the simplicity and harmony of the marionettes – and, for Michael Jackson, at the innocence of children and animals. They don’t wear masks.

Of his mannequins, Michael says, "I guess I want to bring them to life… I think I’m accompanying myself with friends I never had." This is the boy that wants to fly; on a stage he soars into the unreal. "Grace appears most purely in that human which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or in the god."

It is the finest irony that at the very moment when Michael Jackson is seen as a god, when he is lost in voice and dance, he is in fact the most graceful of puppets.

To read more from Rock’s Backpages and find out subscription details, visit the Rock’s Backpages website. Barney Hoskyns’ new book Lowside of the Road: A Life of Tom Waits is out now