LET ME draw back the curtains on a probably wet and no doubt freezing night last winter. A mid-week night of no special significance, save that Joy Division had come marching into town.

It wasn’t much of a welcome. It wasn’t one of those hot jam-packed little-league sell-outs where you can’t get in for the length of the guest list and where breaths are bated in anticipation of something about to turn big. Nothing of the sort. Down in the basement confines of a celebrated Islington watering hole it was relaxed and cool.

In front of the intimate stage, though, a gaggle of about a dozen or so modern boys staked out their territorial rights like there was some sort of conspiracy afoot. Minions were dispatched to fetch the pints. The space stage-front was jealously guarded. Their spick and span muted green tribal colours set them apart from the otherwise dowdy crowd.

They had come, heaven knows where from, for Joy Division. Another Manchester Band.

The last time somebody counted there were somewhere in the region of 72 musical aggregations in Manchester and surrounding areas. Can you believe that?

Since the Pistols played the Free Trade Hall with the fledgling Buzzcocks, Manchester’s home-grown activity has bloomed. It’s become a vital and rich part of the English music spectrum and will be more so with the increasing nationwide diversity of music and lifestyle.

But with the exception of passing enigmas such as Jilted John, The Fall and John Cooper Clarke, the main bearers of the Mancunian standard have been the Shelley/Devoto axis. And unless one of the snotty, smart, toothsome pop outfits that seem to populate the city lucks into a chart hit (most likely candidate: The Distractions), the band that looks dead set to follow Buzzcocks out of merely local and underground acclaim and into the wider limelight – going not least on the rapturous critical reaction to their first album Unknown Pleasures – is called Joy Division.

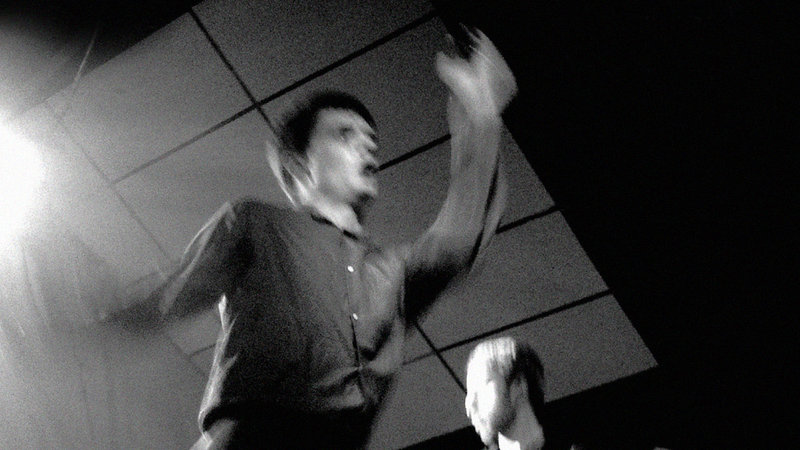

A LONE overhead spot floods the centre-stage microphone and spills out onto the heads of the aforementioned gaggle of sartorial hot-shots. Heads that start to bob furiously at the first pulse of streamlined rhythm, attached to bodies that lurch back and forth, attached to legs that jerk up and down at the knee and arms that swing in a loose crawl or elbows that flap madly. It’s the modern dance that everybody will be doing in the coming months – the one that has succeeded the pogo – and it’s a hybrid of the style that John Lydon copped from the Rastas and the one Mary Mekon of The Mekons invented for herself.

Ignorant of this, and uncaring anyway, the huddle of sophisticated steppers is meanwhile whipping itself up into a frenzy that won’t subside until Joy Division have left them utterly spent.

The spot picks out only this pool of bobbing motion, and the singer Ian Curtis. The rest of Joy Division are shrouded in darkness as they pour out their harsh metal thunder. The singer’s body shakes, rocks and palpitates, a mad dervish of motion and movement all caught in that one mad spotlight.

Were you to shine a torch around this subterranean scene you would see the young, tidy faces of Joy Division and notice perhaps the ordinary neat cut of their clothes. An unremarkable image, with the barest hint of the regimental overtones of their name in the flap-pocket shirts two of them are wearing. You might also notice the growing excitement in the faces of the onlookers, by now all locking into the irresistible motion of the music. Easily the strongest new music to come out of this country this year.

It owes nothing to the after-punk cult of the amateur. If it’s pop, that’s purely accidental. And if it plays with musical perimeters it does so in ingenious, never pretentious, ways – by building carefully on their standard rock basis and using the sounds that can be coaxed from the instruments as textures with which to construct a song. It’s a technique that anyone who listens to the radio these days will be familiar with, from ‘I Feel Love’ to ‘Public Image’, to give but two examples.

Insistent two/four rhythms bait the bristling surface hooks, and their powerdrive is overwhelming. Like The Stooges or early Subway Sect or even Blue Oyster Cult and Buzzcocks.

The themes of Joy Division’s music are sorrowful, painful and sometimes deeply sad. Nothing as badly-refracted and joyless (‘scuse me) as ‘Doll By Doll’ – they’re too compassionate for that – but still music that gives often harrowing glimpses of confusion and alienation. Joy Division walk alone, with their heads bowed.

AT LEAST, that’s my interpretation. Joy Division aren’t giving anybody any clues. They don’t agree with lyric sheets, and that’s something they are very adamant about.

"You get people who seem to think you should put your lyrics on so you can get your message across," says bearded bass player, Peter Hook, with obvious disdain. "They ask us what our lyrics are about and we say, well they’re whatever you hear really.

"We’ve said to people: ‘Haven’t you ever been listening to a record where you’ve been singing a certain line and when you find what it really is you feel let down?’ But they just won’t admit that at all. They still wanted to know what our lyrics were about.

"Don’t you think it’s wrong to pin somebody down like that? Our lyrics may mean something completely different to every single individual."

Is that what you want?

"We’d like it, I suppose…It’s like I just said. You could hear one thing, the bloke next to you could hear something completely different. It means something to you; it means something to him. Why cut him out?"

Why not write gibberish then? On a variation of the monkey-and-typewriter principle it’s bound to mean something to someone sooner or later.

"The songs mean something personal to us, but that’s not the point. It’s like saying, what did Max Escher mean when he did that painting?" He points to a giant print of one of Escher’s typical perspective puzzles that hangs on the wall of Manchester’s Central Sound Studio, where we are now located. "He might just say, ‘I was pissed’. We don’t want to say anything. We don’t want to influence people. We don’t want people to know what we think."

Do you want to know what Joy Division think? What they feel? What makes them angry, bored, sad, amused, anything? What sort of cereal they eat in the morning? What prompts a mournful song like ‘Day Of The Lords’ or what lies behind a lyric like "she took my hand and turned to me and said she’d lost control again"? You’re probably curious, but I doubt that it’s as important to you as the surly defensive Hook seems to think.

That’s how Hook sees it though and that’s all he will tell you about himself and how he sees his music. Besides adding that "people think the lyrics are the guiding force, but we like to think that we influence Ian as much as he influences us; that if we stopped playing Ian would never write again."

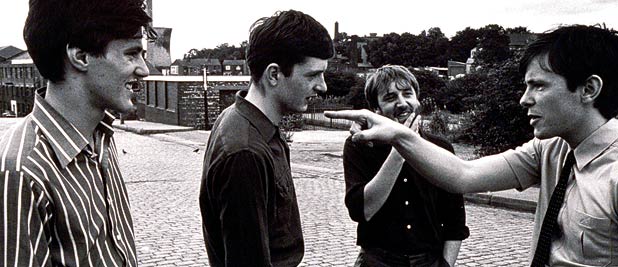

IAN, WHO writes the lyrics, broadly speaking shares these views, but is less reticent. He is off stage the virtual opposite of what he is on. His speaking voice is high and faltering, not swarthy and assertive, and his shyness you would not guess from his onstage abandon.

Stephen Morris, the drummer who completed the foursome a few months after Ian joined, lives, like Ian, in Macclesfield, and owns a huge record collection, partly inherited from his jazz enthusiast father.

"He took me to see Count Basie once…So I took him to see Hawkwind. He was getting all dressed up and I had to explain that, no dad, it’s not that sort of concert…"

He bought his first drum kit by chopping up the furniture in his house to sell as firewood and he’s still searching for that elusive copy of John Cale’s Academy In Peril.

Which leaves only Bernard Albrecht, who plays guitar, and went to school with Peter Hook. By contrast, he is astute and eager to explain himself.

"I don’t like a lot of music," he admits, "but the music I do like I get more out of than from anything else in life. I want to put the feeling that I get out of music back into music as well.

"We’re not ashamed of anything we’ve done in the past. When we started off none of us could play. But each time we go one step forward – and that draws you on. It’s like…I don’t know, it’s just a really good feeling. I think that’s why a lot of people get disillusioned, ‘cos, like, the music dries up."

While Joy Division are talking, Martin ‘Zero’ Hannett is busy inside the small studio mixing some demos of a new version of ‘She’s Lost Control’.

Aside from managing John Cooper Clarke and running the odd live venue and a record label called Rabid, Hannet produced Magazine’s first demos (and their forthcoming single), Jilted John’s hit, the John Cooper Clarke and Joy Division albums, and the latter’s contribution to the Factory Sample EP.

He works like some sort of wizard of the console, occasionally chuckling to himself as he fiddles with the digital devices he’s brought in for the session. His productions are imprinted with a generous but supple use of electronics. He has the auteur’s mark and the entrepreneur’s eye and in the years to come he’s unlikely to fade away.

Joy Division regard Hannet as their sixth member, the fifth being manager Rob Gretton.

Gretton was the DJ at the Rafters Club back in December of ’77, when Joy Division changed their name from Warsaw and played the Stiff Test/Chiswick Challenge night. Seventeen bands slugged it out – Joy Division coming on last at three in the morning and playing two songs.

Tony Wilson, presenter of the bold but badly-received So It Goes, now Factory Records majordomo, was in the audience. "The bands were all good and they were all boring. But Joy Division were wonderful and they had something to say. I thought so and so did Rob, ’cause after that he became their manager."

Wilson recalls another incident from that night. He was sitting next to someone whom he later found out was Ian Curtis, and this someone turned to him, by way of introduction and said: "You bastard. You put Buzzcocks and Sex Pistols and Magazine and all those others on the telly, what about us then?"

As events turned out, Wilson paid for the recording and release of Joy Division’s first album out of his own pocket. 10,000 copies were pressed for a total cost of £8,500. If all the copies sell, and it’s likely that they will, Wilson will recoup his money, and both he and the band will show a profit.

Wilson can afford to be altruistic, since his main income comes from his work as a TV journalist for Granada. Nevertheless the album, Unknown Pleasures, is pressed and packaged to the standard of any other release, if not better, and it’s readily available if you shop around for under three quid.

IT’S RELATIVELY easy to trace the stealthy progress Joy Division have made from their aggressive, noisy, unkempt beginnings in ’77 to the superb controlled heat they generate now. The former is documented for posterity on Virgin’s Electric Circus album, the transition caught on their own An Ideal For Living EP, and a glimpse of their current form was provided by their two tracks on the Factory Sample.

But up until now Joy Division have been dogged by business problems, stalled by personal problems, and ignored. They mistrust the glowing reviews they now get, and wait, dispassionately, for the backlash.

Being on the outside has made them very insular and possessive about their music. It has also given them their strength; not a resentful, we’ll-show-’em sort of strength, but the satisfaction they derive from their music.

"All the business side – that really fucks you up," moans Peter. "Once you get back in the rehearsal room and there’s just the four of us with instruments we’re back where we started. It still hangs over you like a cloud – but once you get your instrument you’re free…"

"You’re always working to the next song," says Ian. "No matter how many songs you’ve done, you’re always looking for the next one. Basically we play what we want. It’d be very easy for us to say: well, all these people seem to like such and such a song…it’d be easy to knock out another one. But we don’t.

"We don’t want to get diluted, really, and by staying at Factory at the moment we’re free to do what we want. There’s no-one restricting us or the music – or even the artwork and promotion. You get bands that are given huge advances – loans really – but what do they spend it on? What is all that money going to get? Is it going to make the music any better?"

Well, it’ll buy more equipment. Whether that makes the music any better is a moot point…But we digress.

"Another good thing about it," says Stephen, from the heart, "is if you’ve got some sort of frustration, something eating you, something you perhaps couldn’t talk to anybody about – you can get it out just by playing."

"The thing is, if you’ve got a brain," explains Peter, "obviously you want to do something with your life, or whatever. I’m sure a lot of people feel like that. Now that we’ve got this, we don’t."

Ian disagrees: "You say that and you’re taking away someone’s self-respect. It’s like that group – what were they called? – someone wrote a song about women at home, and they said: ‘This is a song about all the women who should be out doing what they want’. That’s taking away someone’s self-respect."

Bernard takes up the issue: "People who don’t like what they’re doing either go one way or another. They get out and do something else – whether it’s going off round the world or forming a group or even living the rest of their lives on the dole – and it takes a bit of courage to do that. Or they just settle down at work and just take the weight of the job on their shoulders – which also takes a lot of courage. It’s terribly sad, but then there’s a vast amount of people who don’t even think about it. All they want is a pint every night and two weeks in Benidorm every year.

"And then I bet there are people who think we’re stupid because we’re going into a position where there’s no security – it’s not going to last us a lifetime.

"That’s why we don’t want to state what people should be and how they should interpret our songs, because you just can’t say whether someone’s right and someone’s wrong. Both people can be right at the same time."

"Everyone’s living in their own little world," reflects Ian. "When I was about 15 or 16 at school I used to talk with me mates and we’d say: right. As soon as we leave we’ll be down in London, doing something nobody else is doing.

"Then I used to work in a factory, and I was really happy because I could daydream all day. All I had to do was push this wagon with cotton things in it up and down. But I didn’t have to think. I could think about the weekend, imagine what I was going to spend me money on, which LP I was going to buy…You can live in your own little world."

Too true. But whichever world you choose to live in the chances are it’ll sooner rather than later coincide with Joy Division’s. They’re here to stay.

And one more thing…All over Manchester the sewers have collapsed, the sewage pipes choosing the moment almost to the day to simultaneously end their century-long lifespan and fill the streets with a foul stench. But what you make of that is up to you…

© Paul Rambali, 1979

Rock’s Backpages is an archive of the best music writing and criticism of the past 50 years. Sign up here for the weekly RBP newsletter, listing all new additions to the library