BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN SITS cross-legged on his half-made bed, and surveys the scene. Records are strewn across the room, singles mostly, intermixed with empty Pepsi bottles, a motley of underwear, socks and jeans, half-read and half-written letters, an assortment of tapes, and a copy of Richard Williams’ Out of His Head, the biography of Phil Spector.

The space is small, but Bruce and the two friends listening to Harold Dorman’s ‘Mountain of Love’ don’t mind. They’re listening for the final few bars of ‘Mountain’, in which the drummer collapses and loses the beat – the song slows down to a noticeably improper tempo, and the effect is nothing less than absurd. Unfortunately, Springsteen, unlubricated by anything more than the spirit of the thing, is having trouble getting the turntable to spin consistently. (One of those weird things with the green push button that lights up when you press it.) When he finally does, it turns out the record was warped. It is unplayable. Hysterically, Springsteen sweeps it under the mass of accumulated debris.

"Here," he says, "I’ll play ya something else." He puts on a tape of he and the E Street Band at the Main Point in Philadelphia. Suddenly, out of the speakers booms his own voice, cracking up at what he’s singing. ("That song has some of the best lines," he says shaking his head, "and some of the dumbest.") "Standin’ on a mountain lookin’ down at the city, the way I feel t’nite is a dawgawn pity." When the band comes in, the room is charged. The playing and the singing is rough, even ragged, but it is alive, sparked with the discovery of something vital in an old, trashy song. It has been a long time since I heard anyone get this interested in rock and roll, even classic old rock and roll. It has been a lot longer since anyone has gotten me so interested.

Song done, Springsteen snaps the tape recorder off. "There," he says, with the characteristic delinquent twinkle in his eye. "If that don’t get a club goin’, nothin’ will."

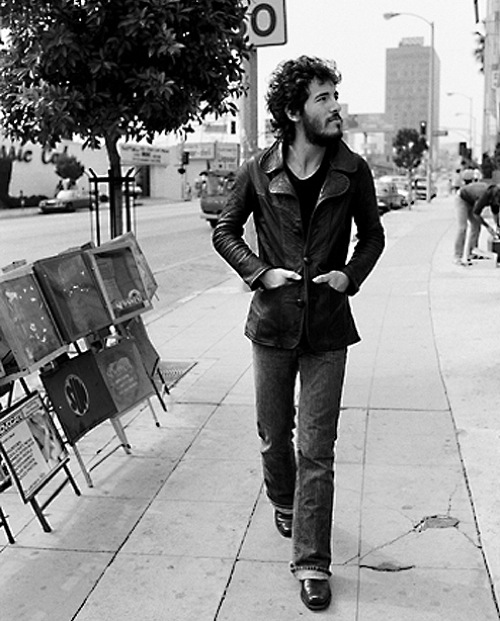

Bruce Springsteen is determined to get ’em going. The magic is that he doesn’t have to be so determined to get himself going. Without being constantly "on." like a performer, Springsteen is constantly on, like someone who knows how good he is. He is full of himself, confident without being arrogant, almost serene in his awareness of what he is doing with his songs, his singing, his band. His music – and nothing gets in the way of that. Unlike, say, Roxy Music, which makes very exciting music out of a nearly desperate sense of boredom, Springsteen makes mesmerizing rock out of an inner conviction that almost everything is interesting, even fascinating.

Take the three songs which, at this point, form the focus of the long-awaited third Springsteen album. Born to Run is almost a rock opera. But, rather than building his concept piece around a derivative European anti-funk motif, Springsteen has built his masterwork around a guitar line ripped straight from the heart of ‘Telstar’. It may be too long (4:30) and too dense (layer upon layer of glockenspiel, voice, band, strings) to be a hit, but it does capture the imagination with its evocation of Springsteen’s usual characters – kids on the streets and ‘tween the sheets – and its immortal catch-line: "Tramps like us, baby we was born to run."

Not that he couldn’t write something more classically oriented, if he needed to. ‘Jungleland’, the ten minute opus which may very well serve as the title of the third record, opens with 90 seconds of strings and percussion. But its influences are classical in the way in which ’60s soul producers like Spector, Holland-Dozier-Holland and Gamble-Huff absorbed them, rather than in the way that pedants like those unctuous Britons Yes and ELP have done. Its imagery is magnificient, exceeded only by its music. Springsteen’s music is often strange because it has an almost traditional sense of beauty, an inkling of the awe you can feel when, say, first falling in love or finally discovering that the magic in the music is also in you. Which may also be first falling in love.

‘She’s the One’, on the other hand, is pure sex, with a Bo Diddley beat that’s nothing short of scary. Shorter, and less complicated than the other two, it could be the one. (The Hollies’ ‘Sandy’ might’ve beat him to it. As Springsteen fans know only too well, the Hollies’ version has almost nothing in common with Bruce’s. But then, what did the Byrds’ ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ share with Dylan’s?)

All of this makes Bruce Springsteen just about what he thinks he is, or at least, hopes to become: the Complete Rock and Roller. Few in rock and roll have attempted so much. None of the ’50s rock and rollers were so ambitious – Elvis could have achieved everything, even intellectual and production brilliance, without drawing a heavy breath, if he had that ambition – and Bob Dylan never had the patience to, for instance, make interestingly constructed records. The Beatles had the production genius, with Martin and Spector and one suspects, without them, but they never really had to tackle it on stage. In any case, like the Stones, their magic was more collective than individual as subsequent events have shown. The Stones themselves couldn’t be everything, because the scope of the group deliberately cannot contain some of Springsteen’s farthest fetched (and I believe, most successful) ideas. For instance, it’s hard to imagine Jagger coming out to sing a ballad as his first song, let alone a ballad sung only against violin accompaniment. Todd Rundgren had the idea, and the scope, but – one suspects – not quite the guts or talent or sheer keening madness to to go out and DO it, as a rock and roller. So he retired to the academy of his own electronic idiosyncrasy.

And Rundgren’s myth was always internal. Because he spent so much time in the cloister of the studio, word had to spread the hard way, by those who shelled out for his records. Certainly nothing to compare with Springsteen’s full-blown stage show, which lately encompasses such tricks as the new introduction to the slowed down ‘E Street Shuffle’: Springsteen recounts walking down an Asbury avenue, late one dark night, and seeing a giant black man at the corner. "I took the money out of my pockets and threw it on the ground. I took my jacket and threw it on the ground," he says, standing in the glare of a single spotlight. "Then he put out his hand" – the enormous black palm of gargantuan, spooky saxophonist Clarence Clemmons suddenly juts into the glare and Springsteen whispers: "SPARKS fly on E Street." It is a truly unforgettable moment, taking on a racial fear at the same time that it devastates it into an almost trivial joke. (And works better because Springsteen’s music so fully encompasses soul influences.)

So it goes with a number of one-liners, moments ("Brace yourselves," he shouted at the beginning of the final chorus of ‘Quarter to Three’, his third encore one night. You had to be there to discover how necessary it was to do that), even songs. I’ve only seen him do ‘Then I Kissed Her’, a remake of the gorgeous old Crystals’ song, once, for instance, and I’ve been thirsting for it ever since. In this sense, it may be to his advantage that he has no record. Not only does word-of-mouth have a chance to spread more completely, but every instant is more special because it is irretrieveable.

That sense that he is special has begun to pervade even Springsteen’s semi-private life. When he showed up at a party for label mates Blue Oyster Cult, Springsteen completely dominated the room. So much so that Rod Stewart and a couple of the Faces, no slouches at scene-stealing themselves, were all but ignored when they made a brief appearance. Yet he has yet to lose his innocence. Going to visit the Faces later that night, at the ostentatiously elegant Plaza Hotel, Springsteen feigned awe – although you wondered if it were entirely feigned – at the mirrored, plushly carpeted lobby.

Fragments of a legend have begun to build. There are the stories about school – in high school, the time when he was sent to first grade by a nun, and, continuing to act the wise-ass, was put in the embarassing position of having the first grade nun suggest to a smaller child: "Johnny, show Bruce how we treat people who act like that down here." Johnny slapped Springsteen’s face. Or in college, the story of how the student body petitioned the administration for his expulsion, "because I was just too weird for ’em, I guess." The news that his father was a bus driver, which gives added poignancy to ‘Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street’. (Which begins, "Hey, bus driver, keep the change.") Aphorisms are not beyond him: On Led Zeppelin: "They’re like a lot of those groups. Not only aren’t they doing anything new, they don’t do the old stuff so good, either." On marriage: "I lived with someone once for two years. But I decided that to be married, you had to write married music. And I’m not ready for that." On the radio: "I don’t see how anyone listens to [the local progressive rock station]. Everything’s so damn long. At least if you listen to [the local oldies station] you know you’re gonna hit three out of five. And the stuff you don’t like doesn’t last long."

All of this goes only so far, of course. A record, a hit record, is a crucial necessity. Sales of the first two albums are over 100,000 but that’s nothing in America. There are still large areas of the country where Springsteen hasn’t played – even important large cities such as Detroit have been left out – and though the word travels fast, and frequently, articles like this ultimately seem like just the usual rhetoric without something to back them up. As one Californian put it, "I’ve heard enough. It’s like having everyone tell me I’m really missing something by not seeing Egypt. When’s he going to come out here?"

Presuming he has the hit he deserves, Springsteen should be hitting most of America over the rest of the year. After an abortive arena journey with Chicago, he is, he says, reluctant to play large halls ever again. But he is one of the few rockers who would have any idea of what to do – except blast – in a room the size of a hockey rink. (Mick Jagger is about the only example who comes to mind, though Rod Stewart and Elvis do pretty well now that I think of it.)

Suppose that he does hit the big time. Even, suppose that he really is, as the ads have it, "rock and roll future." What happens then?

Since I believe that all of the above is true, and is going to happen, I have been at some pains to try to figure it out. Certainly, not a new explosion, a la Beatles and Elvis. Those phenomena were predicated upon an element of surprise, of catching an audience unaware, that is simply no longer operative. Not with rock on nationwide TV too many times a week. And not the kind of quiet, in-crowd build-up that propelled Dylan into the national eye. What Springsteen is after – nothing less than everything – has to be bigger than that, in mass terms, though it obviously cannot exceed Dylan in influence, his biggest achievement.

Springsteen’s impact may very well be most fully felt as a springboard, a device to get people to do more than just pay attention. He can, potentially, polarize people in the way that Elvis, the Beatles, the Stones, Dylan – all the really great ones – initially did. (Already, some early Springsteen fans feel alienated by his ever more forceful occupation with his soul influences.) The key to the success of those four is that as many hated them as loved them – but everyone had to take a position. God knows who he’ll drag into the spotlight with him – it might have been the N.Y. Dolls, whose passion for soul oldies was equal to his, or Loudon Wainwright, whose cool, humorous vision parallels Bruce’s in a more adult (sort of) way – but that ought to be something like what will happen. Sort of the way Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and the other rockabilly crazies followed Elvis.

He’s smart though. He said it all, one night, introducing ‘Wear My Ring Around Your Neck’, the Presley oldie. "There have been contenders. There have been pretenders. But there is still only one King."

But no king reigns forever.

© Dave Marsh, 1975

Rock’s Backpages is an archive of the best music writing and criticism of the past 50 years. Sign up here for the weekly RBP newsletter, listing all new additions to the library