Thanks to the band’s run of magnificent social vignettes throughout the 1960s, Ray Davies of The Kinks became known not simply as a fine songwriter, but a fine British songwriter. While The Beatles and The Rolling Stones achieved transatlantic megastardom, as a writer Davies was forced to look inward after being banned from entering the country between 1965 to 1969, following a dispute with the American Federation Of Musicians. As a result his recordings of the era – 1968’s career-high The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society, being the prime example – are defined by a curiously unique subversion of "Englishness" for which he’s been lauded ever since, a more eccentric, satirical counterpoint to his contemporaries’ pushes towards abstraction and psychedelia.

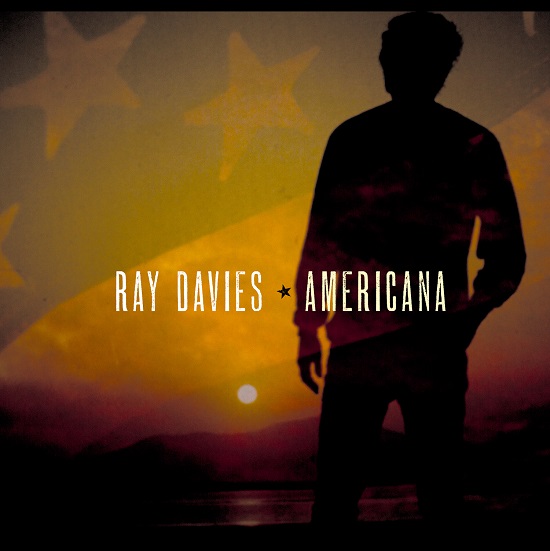

That only tells half the story, for as much as the band’s peak was indeed defined by a deep and cutting fascination with the culture of their homeland, Davies’ relationship with the USA is of equal weight when it comes to analysing his career. His two-album new musical project, the first part of which is released on 21 April via Legacy Recordings, shares a title with his 2013 memoir, Americana, and taken together they form an exhaustive study of a nation with which he’s had a turbulent relationship, Davies turning his writing, still defined by character studies with a satirical bite, to both the joyful and poisonous side of the nation.

Meeting in a bare upstairs room at his otherwise lavish Konk Studios in Hornsey, North London, Davies says he divides his American experiences into three parts. The first, growing up in nearby Muswell Hill in the 1950s, he was captivated by the romanticism of the era’s great Western movies, the be-bop and showtunes brought home by his older sisters as well as his own love of Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, ‘falling in love with the culture’ before being brought crashing down to earth by the second period, his exclusion his late-60s exclusion. The third, "the good bit", would not come until their return in 1970, by which time the British Invasion had come and gone.

How much, then, does Davies look back on The Kinks’ 60s peak with a tinge of regret? "It was a big blow to our career," he says. "Also it was a place where all our musical heroes were. There was all the rock, jazz, blues, and we were denied that in our prime. I was 21 and my brother was 17 [when the Kinks were banned in 1965], we’d had hits there. I think it affected the work we did because we couldn’t tour there, so we had to become more insular and write about village greens. I became kind of entrenched in being English because we couldn’t tour there, and so we became underground, subversive even. Although I did want to play Woodstock. I would have done the national anthem. Jimi Hendrix did their national anthem but I wanted to do God Save the Queen."

When they returned to the States in 1970 the band found themselves a good few rungs lower on the ladder than most of their more politically fortunate compatriots, opening for the likes of Neil Diamond on college campuses across the nation. Forced once more through the slog of getting their band established, Davies says he "really got to know America" as they toured. "Spending time in New York in particular definitely changed my perspective," he expands. "Meeting real people, as far as you can be real in Manhattan. I got to know people in the old man’s bar, the paper sellers, the window cleaners."

New Orleans became Davies’ long term base in the US, a city he first encountered while touring in the 1970s. "There’s an unspoken code of, dare I say, togetherness there," he explains. The appeal was not quite immediate, until a chance encounter with a French quarter marching band playing one of his songs, 1971’s ‘Alcohol’, rekindled his love of Dixieland music and sparked a long-term immersion in the city’s multi-faceted music scene. "When I first went down there to stay longer I was impressed by the lack of musical snobbery, you weren’t a jazz musician or a pop singer or a folk singer, you were a musician. I warmed to that."

Snobbery has long been a bugbear of Davies’. "When I was young I was the youngest player in the Dave Hunt Blues Messengers, they were all older jazz players and there was inverted snobbery there, and there still is now. You’ll go to so-called jazz players and the best of them will play anything. The really scared ones are the ones who say, ‘Oh we only play jazz,’ they won’t make music. There’s a protectiveness, but if you look at the great players like Jerry Mulligan, Max Roach, Billie Holiday, they’re singing their art, they’re not just singing jazz.

"New Orleans reminds me very much of England," he continues of the city. "Small shops, tree lined streets like where I grew up in North London, and the music is just a part of it. I like the social dynamic, apart from the muggers and murderers." He’s alluding to an incident in 2004, in which he was shot by a New Orleans mugger; the joys of the city, he makes clear, do not mask the nation’s faults. "I understand why guns are part of the constitution in a pioneer sense, but then organised crime is another. The guy that pulled the bullet out of my leg said it was a Walmart bullet. He probably bought his gun from Walmart too.

"America is ungovernable. You can govern Louisiana, just about, Detroit, just about, but you can’t govern both at the same time. I think it is what it is, it’s a giant landmass, which is part of the allure, but also it’s a dangerous place, it’s so big that people can just disappear." It’s those kind of themes, the many, constantly shifting faces of the United States, that the Americana project tackles. "There’s a song called ‘Long Drive Home To Tarzana’, for example, about two people just looking for a place to settle. You know they’re never get there. Dorothy Parker said ‘Everyone’s trying to get there, but once you get there you realise there’s no there there’. It’s a long, long way to paradise."

Elsewhere he addresses the duplicity of the American entertainment industry, the death of independence in the wake of capitalist gentrification and more, and with such weighty themes in Davies’ crosshairs, it seems appropriate that Americana should match them in heft. As well as the two albums and the book that preceded them, Davies has plans for "a big theatrical experience. Not to make it a theatre piece, just to have its own identity. Avant garde theatre, visuals, sounds. I don’t want to preach to the audience, I just want them to absorb."

Yet there will always be those clamouring for the hits. He acknowledges that he may have to rework a few of the classics in order for them to fit his new vision. It could well be a drawback to Davies’ creative thirst – he’s already got his sights set on his next project and a number of scores for TV – that he’s so constantly dogged by his own reputation, his place among the Great British Songwriters. "’Great’ is a big word, but first of all I’m a songwriter," he says, giving little away. "Great songs come from Hungary, they come from New Jersey, a great song is a great song, it doesn’t matter. I first wrote songs as a hobby, for my family to see."

It is depressing, but true, that it’s hard to discuss Davies’ identity in terms of its Britishness without the looming spectre of current politics. Is he proud, I ask, to be British? "I’m concerned to be British, because flats are being built but they’re going to hedge funds, as an investment rather than somewhere people can live. Proud is a strange word. Britain’s lost, politically, we don’t know where we are. Big corporations, these cathedrals of consumerism, have taken over our identity."

Davies looks out of the window at the North London street below with a tinge of frustration. "I think one matures, one becomes not embittered but angrier with age because you feel you’ve tried to change things but they’re still there. Unless we deal with it, it’s going to ruin us. Something’s got to happen, this neighbourhood is going to be like a ghetto soon. I don’t know what the answer is, but it’s cruel to tax people who are helpless, people who rely on their business to live. Not every business can run like Philip Green.

"The same thing happened in Manhattan. I lived on the upper west side, in Spanish West Harlem, and it was affordable. When I first rented there in the 80s my next door neighbour was a window cleaner. Now they’re merchant bankers. Gentrification is everywhere, rents have gone up, small shops are going out of business and Costa Coffees moving in.

"Years ago I wrote a show called Preservation. The Kinks would do half an hour of hits then I’d turn into this man, Mr Flash, he was the head of a country called Preservation that relied on corporate money and foreign oil to keep going, it’s a dictatorship where he rules by media. The band members play different characters, Dave was Mr Twitch, the head of propaganda, the drummer Mick [Avory] was the head of secret police, we had a guy called The Bishop who’s a religious leader. In simplistic terms it’s a great morality piece, but very appropriate to now. I’d love to stage it again, it feels very appropriate."

With all that being said, it’s surprising to hear Davies say he’s reluctant to describe himself as political. "A lot of people think that because I write political songs, particularly for Preservation which was quite radically political, that those politics are mine, but I’m a character actor rather than a singer. Those politics belong to the character, not to me." What then are Ray Davies’ own politics? "I’ve never voted," he says. "I haven’t found a political party that adequately expresses how I feel about the world. My dad was a working class socialist, but as a person … I just don’t want people in shops to have to sell their businesses, I don’t know what that makes me [politically]."

That said, he also believes "the time is coming for everyone to find out what they are, politically. It’s got to happen in the next five years. I wish I had time left in my life to be political – I’d like to change things politically. I wouldn’t say run for parliament because you’re already in the system if you’re running. If you’re nailing your colours to the mast you’re part of the system. If I could find a way of being outside the system and still being politically involved, I would."

Speaking of the system, however, it’s worth remembering that since this March he’s been Sir Ray Davies. Reluctant as he is to be "in the system", how does it feel to be knighted? He bats away the apparent contradiction. "When I got the news I thought it was a tax demand," he says. "I thought about it and I thought my parents would be very proud and honoured. It doesn’t make me a better person but I accept it with good grace. I like to think it’s for work in the community, which is basically what I’ve done, rather than be a big pop star in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Because I write about people. It’s like giving an honour to an unknown person, which is what that system does. I like to think I’ve been recognised for good work, not because I’ve had hits."

Ray Davies, then, is a thing of contradictions. At once part of the establishment and eager to escape it, at once one of Britain’s most revered political songwriters but bizarrely reluctant to articulate his politics. Not unlike America.