Tranquility is not the first word that comes to mind listening to Pyrrhon’s music. Their new album, Abscess Time, is almost uniquely successful in manufacturing discomforting sounds: death metal, free jazz, noise rock, doom metal, grindcore… If it’s extreme, it leads. The seething mass of all these elements might be repellent, but it is meticulously assembled. If you hold on tight enough to one of these protruding spikes, the quality of the band’s craft starts oozing out.

Abscess Time is one long, excoriating survey of late capitalism. The results are not good. Things have got so bad that humanity has commodified itself in the systems it has created. As the discordant guitar-neck-slides, blasting-until-collapse and herky-jerky rhythms of ‘Human Capital’ testify: "You joined the portfolio at the moment of birth / Time to cover your cost, time to yield your worth."

When the songs are not stuffing this message down our throats, take it from Arthur Jensen, Chairman of the Communications Corporation Of America, played by Ned Beatty in the 1976 film Network, in the sample that prefaces the song ‘Another Day In Paradise’: "The world is a business, Mr. Beale, it has been since man crawled out of the slime."

His addressee is Howard Beale, a longtime anchor at the corporation’s news station, who has gone off the rails with his on-air ranting – threatening an important deal necessary to safeguard the future of the business. Jensen’’ response is to invite Beale to the company’s Imperial-looking boardroom. There, Jensen closes the magnificent curtains and delivers a speech of demoniac intensity about the cosmology of corporations, the "holistic systems of systems" that transcends nation states and "the international dominion of dollars" which represents "the primal forces of nature."

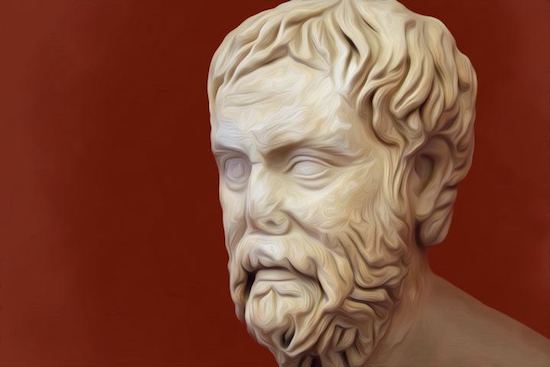

If Abscess Time is a scathing critique of capitalism, where is our recourse? Pyrrhon do not offer much in the way of conciliation in this collection of songs, but their name itself might offer another way of seeing the world around us. ‘Pyrrhon’ is an alternative spelling of Pyrrho, the Greek philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism, a form of skepticism from the 4th century BC.

Can this ancient way of thinking untangle us from the punishing state of capitalism in the 21st century? I decided to involve Richard Bett, professor at John Hopkins University and specialist in Ancient Greek philosophy, to see whether Pyrrhonism itself offered any chinks of light in Pyrrhon the band’s bleak view of the modern world.

I asked Bett how the concept of tranquility is important to Pyrrhonism: "Tranquility (ataraxia in Greek, literally a state of freedom from worry) is really central to Pyrrhonism," said Bett. "This is true for Pyrrho himself (from the little we know about him), and also for the later Pyrrhonist Sextus Empiricus, many of whose writings we have. The idea is that you’re not bothered by the things that bother other people."

On Abscess Time, Pyrrhon seem deeply bothered by the modern condition. Rather than search for a solution or way out of this system, or to peel away the layers to reveal the true nature of things, Pyrrhon have stopped trying. As Bett said to me, "If you’re a Pyrrhonist, you give up on the search and cultivate suspension of judgment, and that brings you tranquility."

There are echoes of this in the bludgeoning song ‘The Lean Years’: "Oh, you know it felt just fine / To live surveilled, revealed inside / Each thought coded and catalogued / To hide nothing, nothing at all." If we let go of an interior life and suspend judgement on what’s good and bad, in turn shedding our anxieties and embracing turmoil because it doesn’t bother us – can this be without costs? As a result, are we not ethical vacuums, passive in our existence and alienated from our own lives?

This has been one of the hardest lessons from the pandemic that pressed the pause button on the markets. The state of lockdown engenders alienation from each other, our own sense of purpose and self, and – most troubling of all – the systems that preserve us. When a global catastrophe strikes, the world suffers as a whole, because we are bound into the "system of systems" that Arthur Jensen describes in Network. That system (with all its in-built inequalities around the distribution of its wealth) will make you suffer when it’s working, but make you suffer more when it’s not. Governments and corporations know this – that’s why you’re being urged to spend money and get back to work in environments with the potential to kill you.

Alienating yourself from the system, taking the route of the Pyrrhonian, carries huge risks. The centrepiece of Abscess Time is the eight-minute-long ‘The Cost Of Living’, with its wending guitar melody that slowly emerges from the primordial swamp. It’s a ragged screed retched out of the pit of singer Doug Moore’s stomach, tracing humanity’s devolution from savage – albeit free – primates ("Once we made our home in the trees / Lived innocent, vicious, free") to enlightened – yet enslaved – lessees of riches ("And now the ground shifts under our feet / And our debts shadow us into our sleep / So that we never rest, we just slave for a seat/ At the table of gold, as if we’re not the feast"). Does the follower of Pyrrhonism suffer this indignity under the guise of bliss, or is it that this is the only way to feel a semblance of freedom?

Professor Bett acknowledges there is a deficiency in Pyrrhonism’s view of the world that inhibits its followers from being proactive in the course of their lives: "A defender of the skeptics would reply that they follow the way things strike them (without committing to whether they really are as they seem), and that this is quite enough to lead a normal life. But in an important sense, the skeptics are not invested in what happens in the world like most other people are (that’s the whole point of the tranquility), and that does seem to suggest a kind of passivity and lack of full human agency. But this is a controversial issue."

This presents a clash with the emotional tenor of much heavy music. If anything, its artists and performers care too much. And if you care a lot, you are also liable to snap. On Abscess Time, the song ‘Down At Liberty Ashes’ is introduced with a sample from Taxi Driver (like Network, also released in 1976), in which the cabbie Wizard (played by Peter Boyle) asserts, "Look at it this way. A man takes a job, you know? And that job – I mean, like that – that becomes what he is." In the rest of the speech in the film, he says he has spent 13 years at his occupation, 10 of those working at night, and ultimately we’re doomed to become our jobs: "We’re all fucked." He is talking to fellow taxi driver Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro, famously), whose response is blunt: "I don’t know. That’s about the dumbest thing I ever heard."

Bickle is the anti-Pyrrhonian. Bickle cannot, and will not, go with the flow. But he is also a product of the 20 century, where the powerlessness and emasculation of working men and women could lead to radical violence. By contrast, Pyrrhonism is about letting the status quo remain. As Richard Bett put it to me, ancient thinkers and philosophers are interested in "cultivating a mindset that best equips you to deal with whatever fortune may fling at you, on the assumption that this is largely out of our control."

But the ancient thinkers and philosophers were also men without work – we have no records from 4th-century slaves and those who needed to toil for food and shelter. As Bett adumbrated: "Ancient Greek and Roman thought has almost nothing to say about the conditions of work and the power systems embedded in the work world. Partly this is because the authors we have were mostly insulated from the realities of the work world. But I think another reason is that the kind of sociological analysis that would bring these power systems to people’s attention doesn’t really get going until much more recent times [e.g. Marxism]."

Pyrrhon have something very pointed to say about the conditions of work in the cacophonous ‘Down At Liberty Ashes’, a song which plays out like a mangled-beyond-recognition first verse of Bon Jovi’s ‘Livin’ On A Prayer’, or sounds as if a guttural Bruce Springsteen wrote dirgey death metal. The song twitches and shifts and grinds. Its focus moves from the real-life Liberty Ashes garbage waste removal fleet in New York, operated by men who "chomp pills to push through without stopping," to the cons "chained to the line" who are "mincing chickens" down in "Okie."

The instrumentation of the song itself becomes the infernal machinery chewing up and spitting out its own operators, enslaved to its machinations. It prompts one of the album’s best lyrical passages: "Out on the plains, he slams booze and weed / To smother remembrance of rancid sliding grain / Compressing his lungs, like industry’s crumbling teeth / In that dire silo where they pulled him free / But lost both his friends." The song compacts and chomps its listener, making its lyrical message emphatic: The big machine eats everything."

Travis Bickle’s most famous line in Taxi Driver ("Someday a rain will come and wipe this scum off the streets") is echoed in the imagery of the opening, title track of Abscess Time: of the human experience as pustule, swollen and full of "The stench of our failures, confined under pressure." Eventually this will burst, and when it does, the streets will be cleaned in a fouler way: "The rush of our pus will bleach the cruel streets / For when all is corruption, no act is obscene."

In Taxi Driver, the big machine does not eat Travis Bickle. Bickle resists the capitulation to capitalism, instead resorting to terrible violence to cleanse his mind and the street around him of "the scum" he has come to despise – the pimps, prostitutes and petty criminals who are byproducts of a system akin to the refuse removed by the Liberty Ashes garbage trucks. But extricating himself from the system the way he does has terrible costs for the characters caught up in the film’s climactic bloodbath. Whether they are victims of the system or Bickle’s individualistic psychopathy, or both, is one of the questions the film leaves hanging.

Unless, like Arthur Jensen, we are safely ensconced within a boardroom atop an ivory tower, perhaps we are all rats fighting in a ditch – especially online. On album closer ‘Rat King Lifecycle’, Pyrrhon take that image, of the dopamine-addicted social reinforcement of someone "Nestled in your cortege of suck-ups and betas," then stretch it out to rat-race work culture as a whole. In this woozy, nightmare vision, us sewer-dwellers rarely get above street level: "You’ll learn to aspire, eye the climb up the ladder / Master the tunnels, subsisting on refuse." The beginning and the end of our lives are the same, where "The final instinct will be recursive gnawing /Among your brothers."

In this plague year, it is apposite to talk about rats. The pandemic has slowed our working habits and given us a chance to actually think about each other’s welfare and imagine a better world. But will we take that opportunity? In a recent interview, Naomi Klein said the virus, brutal as it is, has made us stop, think and feel more: "When you slow down, you can feel things; when you’re in that constant rat race, it doesn’t leave much time for empathy. From its very beginning, the virus has forced us to think about interdependencies and relationships."

And what if the rat race simply starts up again when all this has passed (if indeed it does pass), more furious and unforgiving than ever? Travis Bickle’s nihilism won’t solve our problems and Pyrrhon are not ready with answers either. Pyrrhonism does not recognise the systems of work culture that we have today. As for death itself, and the destruction of the human body which is death metal’s principle theme, Bett explained: "There’s a saying attributed to Pyrrho, that there’s nothing to choose between life and death; but the same saying is attributed to other people who had nothing to do with Pyrrhonism, so I wouldn’t put much weight on that."

For the ancient philosophers, death, as with many other aspects of life, is not worth worrying about, because you also need not fear something you cannot control. As Bett explained, "It [death] certainly preoccupied some other Greek philosophers, most notably the Epicureans, who devoted much attention to arguing that there’s no reason to fear death (because there’s no ‘you’ left in the dead state). Sextus must have known these arguments, but at least in the works of his that have survived, he doesn’t address them. Still, I guess he probably would have opted for some version of […] death coming eventually anyway, so there’s no point in worrying about it."

Why worry about being a good person either? Bett revealed to me the ambivalence at the heart of Pyrrhonism towards the notion of a life well led, where a commitment to adhering to a moral code is loose at best: "What they [the skeptics] do invite us to do is to live a life that follows the way things strike us, which includes the laws and customs of our society; so if you do that, you will of course live a conventionally acceptable life. But you won’t be committed to the correctness of those conventions, or of any other ethical principles, so you won’t really be a genuinely good person as most people would think of it."

Pyrrhon’s Abscess Time is a dire portrait of humanity’s subjugation to the systems it has created. Its contorted, agitated sound is extreme metal itself being hurled into the blades of an industrial mangler – ground up until it is almost unrecognisable. It is also a gleeful derangement of Arthur Jensen’s cosmology of business.

If our current historical crisis does represent the rupture of the festering boil of capitalism, we have received an unprecedented opportunity to cleanse ourselves of its purulence for good. But if we cannot, if the capitalist abscess pushes through again worse than ever before, for the sake of our collective sanity we might have to walk the streets with the Pyrrhonian outlook: indifferent, tranquil, and uncommitted to recognise its good, or its evil.

Abscess Time is out now via Willowtip