With a strikingly militant aesthetic, an arsenal of politically-charged and frequently controversial lyrics, and a wall-of-noise approach to musical composition, Public Enemy not only helped to spread hip hop to a whole new demographic, but became figureheads for a more serious and socially-conscious face of the genre, taking the spirit of earlier rap cuts such as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s ‘The Message’ and running with it.

Sadly, though a number of artists would follow in the group’s footsteps – from The Coup to Dead Prez to Mos Def to Saul Williams – it’s probably fair to say that, for the most part, hip hop has travelled a long way from the heady days of the 80s and early 90s – and not necessarily always in the right direction. Indeed, as the genre finds itself staggering through a minefield of pop hooks, pitch-corrected vocals, sanitised lyrics, overt commercial pressures and creative stagnation, the need for firebrands such as Public Enemy seems more pronounced than ever.

Thankfully they have never really gone away.

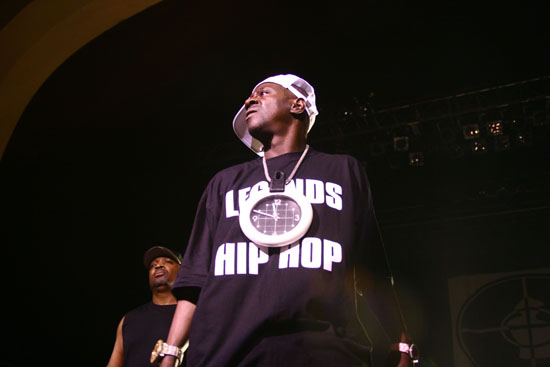

Consistently active in the studio since their 1987 debut Yo! Bum Rush the Show, the band have also been one of the genre’s most visible artists in the live arena. In the last year or so the group have embarked on a series of tours with a bolstered line-up including live instrumentation, hitting new territories while celebrating their most iconic material as well as new numbers from recent albums such as the epically-titled How You Sell Soul to a Soulless People Who Sold Their Soul? The Quietus managed to catch up with the busy man that is Carlton Ridenhour, better known as lead vocalist and group figurehead

Chuck D, to shoot the breeze on about the state of hip hop, touring and live music in the modern age.

Chuck, it’s been 23 years since Public Enemy broke into the wider consciousness thanks to debut album Yo! Bum Rush The Show and the pivotal 1987 Def Jam tour and you’re still out there touring harder than ever. What has 2010 meant for Public Enemy?

Chuck D: Well this is a really significant year for us as it’s the 20th anniversary of the Fear Of A Black Planet album. It’s been a year and a half tour with eight different legs; the sixth leg being South Africa and Nigeria, seventh being Australia and eighth is probably going to be the west coast of the United States. We’ve been touring South Africa for the first time, because we believe Africa could be the centre point of hip hop and rap music, since the United States has pretty much lost that privilege. And the fervour and attitude in Africa is pretty much the same as that in the UK in 1987, it’s crazy.

So what would you say Africa can offer in terms of hip hop music and culture that America has lost when it comes down to it?

CD: KRS-One almost put a boycott on American rap, ‘cos it’s corporate control around the world. Hip hop – on a mainstream basis at least – is corporate driven, corporate dictated, it’s like, ‘We’re gonna tell you what it is’, then you have a whole new generation growing up on that definition. So Africa could be the turning point. There are so many African hip hop/ rap fans, MCs, artists, it’s back to the root of really using it as a way of life, so that’s an opportunity to bring it back to at least where the balance should be. There’s a lot of folklore going around in South Africa that competes against that radiation coming out of the United States or the western world, so there’s a whole lot of combustible energy for a lot of reasons.

Going back for a moment to that legendary 1987 Def Jam tour, did it take you by surprise to come over and see how dramatically things had taken off in the UK?

CD: It didn’t take me by surprise, ‘cos I was one of the rare people on Def Jam that was actually doing press, because of my topics and what I would delve into. So as everybody else was caught up doing in different things in ’86 and ’87, my press had started to be just as significant over in the UK as in the States. We had people coming over from the UK before our first album was even out. It was a surprise to people like LL Cool J and Eric B. & Rakim, ‘cos things were more music and radio-driven [for them], it was about the popularity of a certain adolescent audience. When they came over to the UK they were totally culture

shocked and surprised, they couldn’t understand the level of fever for us.

During the late eighties and early nineties, hip hop obviously had plenty of space within it for politically-minded artists such as yourselves and KRS-One. Two decades later do you feel hip hop can again be a vehicle for political discourse ?

CD: It already is. It’s more about [whether there’s] endorsement and coverage of the people who are doing that out there. There’s a lot of incredible artists out there doing great things, but I think some of the answers are going to be in different categories; people will say, ‘I’m going to get a different brand of rap, rather than what’s put out there on radio for the masses.’ That’s already happening, but I think things are going to really niche themselves, people will say I don’t write about that shit, I write about this.

Without wanting to flatter you too much, it’s fair to say that Public Enemy have been responsible for some of the best protest songs ever written, whether in the genre of hip hop or outside. Who else would you say is out there making protest music right now?

CD: That woman M.I.A, she’s saying something about what’s going on. We have a video called ‘Say It Like It Really Is’ and we put a lot of people in there that I really look up to. It became more known for who it left out than who it had in, but there was nothing intentional there. Sadly I [accidentally] left out Arrested Development and [vocalist] Speech, Brother Ali, a few others.

But do you think a band as political as Public Enemy could get into the charts and reach a mainstream audience today?

CD: Well we came as a collective, a whole bunch of diverse ideals and talents. When people say, ‘Who came in your footsteps?’ You can say The Roots, but you’re talking about a band that’s a 20-year thing, so they ain’t spring chickens. People like Mos Def and [Talib] Kweli, it’s almost like an ‘experienced veteran’ niche, they’re like 35, 40 years old. Who is out there that’s teenage or twenty years old? I think there’s a lot trying to vie for position, but they’re probably not getting the record deals, they’re probably not doing anything that can sell 600,000 copies. So is there a recruitment or acknowledgement of someone that’s in the seventh grade? People say, ‘No, they’re fucking kids.’ But if an older guy doesn’t raise his game and talk about something different, what separates him from a sixth grader? They can’t share the same topic. You shouldn’t have a 35-year-old person trying to appeal to 6th grader, that’s like paedophilia.

That’s interesting, I was talking to Jaz Coleman of Killing Joke recently and he was talking about a conscious attempt by the powers that be in America, to keep entertainment and popular culture no higher than a sixth grade level. I guess mainstream hip hop could be seen as a pretty good support for that theory.

CD: Then the artists should all be in the sixth grade – that’s acceptable. But the labels will say they can’t sign someone under 18, so they try to get someone who will appeal to that audience. That’s a serious problem. Then when you have people saying, ‘Yeah, I’m talking about sex and chicks’, it’s like, ‘Okay, cool, where’s the other 80 percent?’ Of course you can always sell sex to a kid, without question, they’ll get the credit card and off they go, but I think older MCs have to expand their topic range and their artistic range.

It seems like artists, and perhaps people in general, are ncreasingly hesitant to risk talking about real issues. Why is it do you think we live in such politically unmotivated times? In many ways people have got it harder than ever, none of the topics prevalent in the eighties have gone away, but no-one is really causing a fuss.

CD: That’s what the powers that be want, for you not to say anything and be controlled, simple as that. Live your life, do what you gotta do, and don’t make no noise about it [laughs]. They’ll tell you that you have the right to speak, the gift of language and all that, but there’s an underlying fact, a fear factor that’s making people afraid to say what’s on their mind. 20-years-ago there was a lot of people saying a lot of things because they were in tune with their surroundings, and they saw something which didn’t gel with their surroundings. It wasn’t an individual thing, it was like me and my family – ‘cos even if I’m doing alright my brother or my mother or somebody is having difficulties – my neighbourhood. But once you have individualisation take place, for example technology and the social networks, people move into their own spaces. They don’t have to be part of a literal community ‘cos, hey, they’re part of a virtual community, so they don’t have to gel with someone in their own space.

At the same time you’ve been someone who’s actively sought to harness technology, via blogging and the Public Enemy homepage and have done much to argue for peer-to-peer sharing. What good would you say has come from the digital revolution in relation to music?

CD: One of the best things that has happened is that we’re finally eradicating four areas that ain’t got nothing to do with music; shipping distribution, manufacturing and warehousing. And maybe even taken some of the shine off what is called marketing, ‘cos that’s an overused term and dictates what kind of music people make, and that’s what’s twisted the record industry into a downward spiral. Then they blame it on everything else. In the end you got to check your product. It’s like once people feel they don’t need it – ‘cos its not food, shelter or clothing – if people feel they don’t need it, you need to come up with some kind of something. Cos people feel they need the NBA in America, they feel they need basketball. The integrity and the entertaining value there is kept high.

You’ve been in the music industry for over two decades, why do you think it’s in the state it is?

CD: A lot of people are not happy with their jobs. The artists are not happy doing their jobs with a label having a 360 degree hold on their money. The journalists are saying, ‘Well, there’s a lot of shit out there’, but hearing it just once does not constitute really listening to it. DJs are saying there’s a lot of shit out there, but seriously if you got 1,000 mp3 files and you’re spinning them in a club, how much are you really listening to it? So everybody is in this technological age, but are overworked with a whole bunch of obligations. For example, as a journalist you get a lot of music to review right? Can you review it all? Do you have choices, do people say, ‘Well, I think you need to review this and not that,’ and then how much of it becomes a burden, checking out something and having to make an evaluation of it? How much does that become a burden, if you have a million audio files in a six month period? The genre doesn’t do a good job of filtering. It’s different for sports.

What do you see as the solution? What could the music industry learn from the sports industry?

CD: You have to have more people like you, thousands more and committed to the music world, journalists who understand all those other areas around the art. You know I make that parallel to sport because they cover it all, there’s no surprises. Music I think there’s a lot of laziness from the artists right on up. Sports does a good job of filtering everything because of the amount of people who are in the industry dedicated to maintaining the integrity of the sport, they’ll find that person, they’ll find that incredible football player even if they’re in Xi’an. You cant say, ‘Well everybody’s wearing trainers so there’s too many people wearing trainers, too many people playing football: no, the cream will rise to the top because there’s an infrastructure and a standard that is fought for and understood.

So you feel the music industry needs to provide the same support and nurturing to artists that athletes are provided with?

CD: I think artists are all trying to be what they have to be, it’s unfortunate that they have a lot of restraints trying to that take them to a lot of other areas in order for them to survive, and give them a picture of how they’re going to be successful. I mean you should at least have someone to coach you and get the most out of you as a talent, that’s the difference between talent and skill. When people feel they can do what they’re being told to pay a lot of money to go see, eventually they’re going to be like, ‘I don’t know if I want to be in awe of that, ‘cos I feel I’m better than that’. That’s the problem. In many cases there are a lot of artists out there who are incredibly gifted but there’s an unbelievable lazy factor going on that’s keeping the audience away.

Your live shows have always been explosive affairs and you’ve continued to expand that side of things, notably with the increased emphasis you place on live instrumentation…

CD: You don’t want to knock people for their favourites – that could be Jay Z or Li’l Wayne or whatever – but when somebody never ever comes [and plays live] or comes and plays for 25 minutes, people are like, ‘What the fuck?’ It’s important for us to come and leave people hammered man, gotta leave them smashed. You don’t want them to just be a consumer; like you got some shit selling out of Tesco, then they see you and think, ‘Well I can do better than that’. But that’s become acceptable because the generations shifted, where they have no expectations, they think it’s acceptable.

It seems like for a lot of big name performers, it’s enough just to be there on stage.

CD: Yeah. The same thing that has created artists out of Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian, it’s like, ‘What do you do?’ They just are. They’re in the VIP, and it’s like, ‘Wow, Paris Hilton is here’, and it’s like, ‘Okay, but what the fuck is she going to do, other than look good?’ So it’s like the spectacle has become the performance. I mean [Flavor] Flav is a reality star now, but the core of that is that he has created a niche in the music, and he’s one of the greatest figures in the art form of hip hop or rap, bar none. He can be at a spot and people will say, ‘Okay, Flavor is going to be there, he might perform, or get on the mic and make us laugh, but not just be.’ If that’s the case we might as well start digging up corpses. You know, ‘We have the remains of King Tut in the house tonight!’ [laughs]. And there’s plenty of entertainers, you know, ‘We don’t have Jim Morrison here, but we dug up some of his remains and they’re right over there in the glass case’ or, ‘Yeah fuck, we got Hendrix’s remains over here’. I mean I talk crazy, but it might be an idea for promoters, fifteen years from now. ‘Yep, they’re not here… but we were able to get their travelling remains!’

It’s not so far fetched. It wasn’t so long ago that the likes of P.T Barnum were exhibiting the bodies of the infamous dead…

CD: P.T Barnum came up at a time when people were dirt poor, so to get a dime out of them you better blow their skulls off. So something needs to blow people’s skulls off. I don’t buy this thing where you have a load of bombs going off [on stage], it’s about the human interaction in the performance. But it takes effort, there’s nothing like it, you already have the art working for you and when the artist figures out the dynamic within. Whatever you make, people are still going to want to go out. But we’ve seen a drop off in the effort of artists to do all they can to push forward with what they created. People are thinking, ‘I really enjoyed the art or the video and now I’ve seen them perform and I don’t get it, they’re not giving it to me’. It’s like I see they would rather be rich than entertain people. I think the artist has to make an undying effort, he has to separate himself from his family fanbase, he has to leave [other] people in awe, like wow, even if the ability isn’t that great the effort has to be 100, 200 percent, and that’s probably been the biggest missing thing, there’s been a real drop off on effort. Bottom line, you’ll always have someone who wants to go out, leave their doldrums and go out have a good time. I wanna have my night or day enhanced by something, I wanna be entertained.

Is it important for the audience to be educated as well as entertained though?

CD: You want to be schooled on things. I’m a patron, so it’s like, ‘Leave me with something.’ Some people will leave you with a night, some people will leave you with a lifetime.

The live aspect of music is clearly a focal point for you, so going back to your early days, who were the performers who really impressed and inspired you?

CD: Rick James. I remember a time I just had my mouth open watching Rick James, like, how could a cat be that good? He just played with peaks and valleys, he would sing a ballad then do something raw. I mean he’s hardly ever talked about. That was the first superstar that we met as a group in Buffalo in 1987, on the Licence To Ill tour with the Beastie Boys. He came backstage to visit us, but I went to many Rick James concerts before that and was in awe of his performance.

James Brown was obviously another influence, which surfaced in your beats and samples, but the Public Enemy show is not unlike a James Brown live show in many respects. Was that someone else who impressed you live and offered lessons in terms of live showmanship?

CD: Yeah, you would just be staring in disbelief. You didn’t need smoke or bombs on stage, you were just looking at the guy thinking, how could he do that, it wasn’t just about dancing, it was like how could you be in a non-stop perpetual entertaining motion? When Public Enemy tours around the world we get the strongest performance, but it’s never been as strong as it has now. There’s a bunch of factors that have just come together, it’s not planned, it’s just come together like this. You know, it’s like when Metallica steps into a place, you can be like, ‘Fuck them, I don’t like that heavy metal shit’, but you can see they’re really serious and you’re gonna be intimidated. Not just ‘cos it’s loud but because it’s in synch. Another one is Rage Against The Machine, Led Zeppelin, The Beatles even; when they were singing a soft song on the roof. That was an idea when we organised the press conference before our O2 [arena] show in London, but we couldn’t scramble together to get a spot in Piccadilly Circus.

Some people might be surprised to hear you mention those names from the rock world, but of course in your classic cut ‘Bring The Noise’ you name-check the likes of Yoko Ono, Sonny Bono and Anthrax, the latter of whom you ultimately rerecorded the song [‘Bring Tha Noise’] with.

CD: With Anthrax, we share the same management area, and Scott Ian used to wear Public Enemy shirts when he would do like Donnington festivals and I would be going, like, ‘Wow, Scott’s wearing a Public Enemy shirt that I designed.’ So he did that, I name-checked him in the song, then we became in contact, and he wanted to do the cover. I was like, ‘Well you can do it’, and he was like, ‘Come on’, so we did it, and we did the video, and became comrades. There was two generations there in that song. Sonny Bono; Sonny and Cher, Yoko Ono, Yoko and Jon Lennon, it’s almost one of those things where it’s six degrees of separation. The song was about, well, we have a great respect for these people, and you don’t think that we do, you know? If you’re going to call our music noise, then we’re all part of the musical family… It’s all the same.