Portrait courtesy of the Howard Thompson Archive

“Hiya dk. It’s all your fault. Love you to bits.”

So declared “thinman” at the end his one and only post in Burned Down Days, The Psychedelic Furs’ “officially unofficial” online forum, in August 2004. “thinman” was Andrew Eldritch of The Sisters of Mercy and the object of his affection, “dk”, was Duncan Kilburn, the original saxophone player in The Psychedelic Furs.

Eldritch/thinman had momentarily stepped into the light to explain his enduring gratitude. “The Sisters foisted an early demo tape on Duncan while lurking at a Furs sound-check … at a university whose identity I have forgotten, although I remember the layout and look of the place very clearly. Because it was important.” If not quite an origin myth, the handing over of the cassette in 1981 has acquired legendary status in The Sisters’ narrative.

Because it was important.

It initiated a Furs connection that over the next two years enabled The Sisters’ first great record, earned them their most high profile gigs up till then and brought them significantly closer to the centres of industry power in New York and London.

As significant as the tape handover was, Kilburn and Eldritch do not agree on its location.

In Burned Down Days, dk remembered the Ground Zero of the Furs / Sisters relationship as Leeds University. This is demonstrably false. The Furs did not play at the University until October 1982, by which point Kilburn was no longer in the group.

For his part, Eldritch has tentatively identified Huddersfield Polytechnic as the location of the handover. He told tQ in 2016 that he and his then-girlfriend, Claire Shearsby, went over from Leeds to see The Furs. “We hung around at the soundcheck and I gave a cassette tape of our demo to the saxophone player. He took it to the rest of the band.”

The Furs did indeed play The Great Hall of Huddersfield Poly on 27 May 1981. But this is not where the handover actually happened.

The night before their Huddersfield gig, The Furs played Tiffany’s, a large disco in the centre of Leeds that put on bands on its off-nights. Claire Shearsby remembers that “Andrew had been making these cassettes that he sent to record companies. We decided to go down to the soundcheck at Tiffany’s and give a tape to The Psychedelic Furs. When we got there they had just finished and were heading to their hotel and Andrew handed over a cassette at that point.”

Shearsby was the DJ that night, so access to Tiffany’s would have been easy for her and her boyfriend. The Furs had been booked by the great Leeds promoter, John Keenan. Shearsby had been his regular DJ since the punk summer of 1977.

“When The Psychedelic Furs came back from the hotel,” she continues, “they said the cassette was really good and invited us to go to the gig at Huddersfield Poly the next night. I couldn’t go because I was going to college but Craig (Adams, The Sisters’ bass player at the time) went with Andrew the next day.”

The tape handover and its sequel took place during The Furs’ tour to promote their second album, Talk Talk Talk. The significance of these interactions would not have been lost on Eldritch. He had seen The Furs’ “first gig in Leeds at The F Club, all 25 of them lined up across the front of the stage, a six inch high stage, nose-to-nose with the crowd. They just blew the place away, all of them in black, all of them wearing shades and just bringing the house down.

“I was such a fan. That first album is still one of my top three albums ever. And I’ve always thought that Richard Butler (The Furs’ singer), who funnily enough went to school down the road from me – one of the schools I went to – that him, me and Michael Stipe write in much the same way and have a similar density of lyric. I’ve always been enormously impressed by that band.”

Gary Marx, the guitar player in The Sisters of Mercy at the time, had also seen The Furs live “and liked them, but Andrew really saw some strong parallels with what he was trying to do.”

Although meeting members of one of his favourite bands for the first time – whether it was in Leeds or Huddersfield – Eldritch maintained total sang-froid. Perhaps this was a function of the insouciance of the Leeds’ music scene or the democratisation of punk. Perhaps it was the clarity and confidence that a dab of whizz brings.

Despite having been “not that well, if you catch my drift” in this era, Kilburn does remember a lot about this encounter with Eldritch. “In that early exchange, he came across as interesting, cool and extremely intelligent. He managed to let me know that he finished The Times crossword typically in under ten minutes, he’d been sent down from Oxford and dropped out of Leeds; all impressive and eye-catching factors for me.”

The key detail, which is not disputed, and the root of Eldritch’s affection, is that it was Kilburn who accepted the proffered tape. John Ashton (The Furs’ guitarist at the time) recalls “Andrew clutching this tape” and that “Duncan was the one that stuck his hand out, quicker than I did.”

Kilburn had a reputation for being the most abrasive, aggressive and paranoid member of The Furs, seemingly the least likely to show largesse to strangers pestering him at soundcheck. He explains his actions thus: “When we were being pretty obnoxious very early in The Furs, a member of our road crew came up with the line, ‘Be nice to people on the way up because you’ll need them on the way down.’ Others didn’t heed it but it always rang in my head when these little encounters took place.”

Kilburn doesn’t have any memory of what was on the tape, but Ashton remembers that “Duncan and I both listened to it a lot” in the transit van they were touring in. “This tape stuck out,” Ashton continues. “It was rock with drum machines. At the time there were bands that were electronic-y sounding but this was much more aggressive and Metal. The closest thing to it was The Human League and their drum sound but The Human League was all synths and this had guitars and it was pumping. It was Suicide-meets-Iggy-meets-Motörhead.”

The cassette included primitive demos for a proposed four-song Floorshow EP. ‘Lights’, ‘Adrenochrome’ and ‘Floorshow’ itself would eventually find themselves on later Sisters records in superior forms. The EP also included a version of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Teachers’, which kept Cohen’s lyrics but no semblance of his music. ‘Damage Done’, The Sisters’ first single and its B-sides, ‘Watch’ and ‘Home of the Hitmen’, were also included, along with live recordings of covers of ‘1969’ and ‘Sister Ray’ from a gig at the University of York on 7 May 1981. There were also five more live tracks labelled “St John’s, Leeds 4.5.81”. These were recorded in Eldritch and Shearsby’s top floor flat on St John’s Terrace in the Hyde Park area of Leeds.

“The St John’s stuff,” recalls Gary Marx, “would be just like an early rehearsal with us all in their one room bedsit. I think my gear would actually have been set up on the bed. That wouldn’t constitute a great deal: I was still playing through my old portable record player with a homemade cable, splicing a DIN connector and guitar lead. An audience of one most likely – Andrew’s cat, Spiggy.”

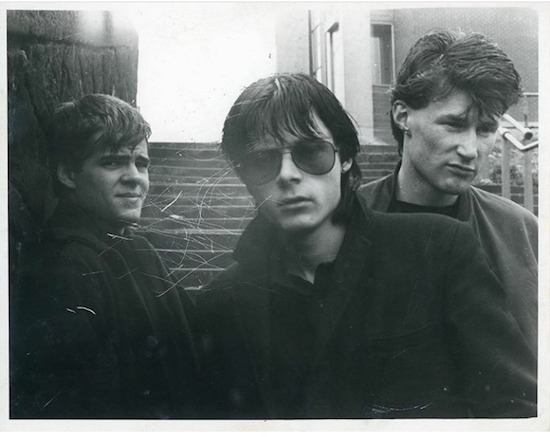

The Psychedelic Furs – spot the T-shirt

Eldritch’s plan had been to use the cassette to get a support slot with The Psychedelic Furs. Ultimately, the plan worked but there was a 17-month interim: the cassette handover took place in late May 1981 and The Sisters finally supported The Psychedelic Furs at five gigs in early October 1982. In those 17 months, thanks to the Furs, The Sisters forged vital industry connections on both sides of the Atlantic and, more importantly, made one of their greatest records.

In fact, both Kilburn and Ashton rapidly became proto-Sisters fans. Eldritch had given both of them T-shirts bearing his first attempt at the Merciful Release logo, the now iconic Head & Star. Ashton was photographed wearing his in Canada in July 1981. Kilburn admits that “although a lot of the stuff has gone in the dumpster over the years”, he still has his Sisters T-shirt somewhere, even though “I lived on a boat for ten years, [where] you really [have] to pare it down.”

Ashton recalls: “Duncan had said to me at one point, ‘You’d rather be in The Sisters of Mercy wouldn’t you?’” Indeed, Ashton readily concedes that “although Talk Talk Talk was a pretty full-on, aggressive album, there are some other songs there that were a little lighter, a little more poppy.” Ashton craved some pumping Suicide-meets-Iggy-meets-Motörhead.

Yet initially The Sisters’ focus was on Kilburn. “The Sisters asked me to produce some material,” he says. “I was keen and met up with them to listen to some stuff. I think we were in a pub or club. I have a very vague but persistent memory of this. They (not just, or even Andrew) insisted that the entire backing track be recorded using a Stylophone. They had one with them.

“I thought it was a joke and it ended there. I was looking to go into a 48-track studio and try my hand as a producer, not messing around with a kids’ toy and a Portastudio.”

Gary Marx comments: "[That] story is hysterical but I can’t really give it any validation. The only piece of equipment I can recall us having that gets anywhere close to the toy shop appeal of the Stylophone is the first Wasp synthesizer. Craig had one – or the use of one – and we used it to generate a pulse of white noise that was the basis of our drum track on the earliest things we did. That pre-dates meeting Duncan by some time, so I can’t imagine we were still using it at that point – a shame if there isn’t some truth in his tale.”

Whatever happened, Duncan Kilburn was soon no longer a member of The Psychedelic Furs. In late 1981 at the end of the Talk Talk Talk tour, the long knives came out.

“It was a particularly rough minivan tour,” admits Ashton. “Everybody was drinking on the ferry back to Britain: just horrible. I remember Duncan throwing a beer over Richard. Later, Richard called me up and said, ‘I can’t take Duncan anymore. You need to go with me or him.’ I didn’t want to not be in The Psychedelic Furs, so I went with Richard. Richard said we should get rid of Roger (Morris, the other guitar player) too. I said, ‘I could use more room.’ I later realised what a big fucking mistake that was. It was stupidity and naivety.”

Therefore, in 1982, it would be John Ashton, not Duncan Kilburn, who would be the member of The Psychedelic Furs who would make the greatest impact on the music of The Sisters of Mercy. Nevertheless, it was Kilburn’s acceptance of the demo tape one afternoon in West Yorkshire that set in motion the series of events that would bring Ashton and The Sisters of Mercy together.

Soon after listening to the cassette, Kilburn and Ashton both, but independently of one another, told Howard Thompson, the hugely influential A&R man who had signed The Furs to CBS, how impressed they were by The Sisters. Shortly after that, Thompson “met Andrew Eldritch in my office at CBS, Soho Square. He was smart, and I liked him immediately.” As well as “the infamous cassette”, Eldritch also gave Thompson “an early photo of the band: three guys – Craig, Eldritch in shades, collar up and Gary.” This is the earliest known publicity photograph of The Sisters of Mercy. It had been taken just off Bellevue Road in Leeds by Jon Langford of The Mekons.

Thompson also saw The Sisters play live. “There’s an entry in my 1981 diary: ’June 13th, Sisters of Mercy, Leeds University, 10pm.’ It seems likely I went to the gig, as I also had a meeting with Susan Fassbender in Bradford earlier that day.” This gig was in the Riley Smith Hall in Leeds University. On the bill were two other Leeds bands: Pink Peg Slax and The Expelaires, Craig Adams’ former band.

The Sisters Of Mercy by Les Mills

Thompson was impressed by The Sisters, although allowances had to be made. “Bands at this stage of their careers are usually pretty undeveloped, figuring it out. I don’t judge them by how unformed their act is, the shitty sound or the crummy environment. I thought Eldritch was a commanding frontman from day one. Reminded me a little bit of Dave Berry. Both wore black and leather well, and could ‘slink’ better than everyone else.

“I’ve always been drawn to people outside of the mainstream,” Thompson continues. “They’re far more interesting. Plus, I like singers who don’t sound like anyone else. Andrew fits right in there. Also, he had infinite appeal to both boys and girls and The Sisters’ audience/crowd was mondo sexy.”

However, Thompson had no intention of signing The Sisters. “At that point, it would have been too early in the band’s development for a label like CBS to jump in.” Also, by the end of 1981 it became clear that Thompson would be moving to New York as an A&R exec at Columbia. Nevertheless, Thompson had someone in mind to guide The Sisters in his absence: Les Mills, the manager of The Psychedelic Furs.

Mills had become The Furs’ manager around the time they were making their first album in 1979. As Ashton drolly recalls, “Les had expertise: he’d roadied for the Banshees. What more do you need?” Also, Mills had been responsible for the infamous “Sign The Banshees Do It Now” graffiti campaign. “That was in my amphetamine-fuelled days,” says Mills. “I made a list of all the record companies in London, got a pack of fat magic markers and went round every record company. The West End was easy, but I even went out to Island in Hammersmith. I walked all night long.”

“We used to joke that Les wiped the gob off Sioux’s mike stand,” says Kilburn. “He was a hustler, spiv and hyperactive. All the things you need in a manager,” he adds sarcastically. “I really wasn’t a big fan.”

The feeling was mutual. “When Duncan and I would get together in the same room,” says Mills, “it would never be amicable because Duncan, from my perspective, was always one of the most obtuse, difficult people I’ve ever had to deal with.”

Mills was about to meet someone who could take obtuse and difficult to another level. Early in 1982, Les Mills met Andrew Eldritch for the first time.

Mills worked out of an office complex in London near Southwark Cathedral. One day, as he was arriving, he noticed “there was this skinny guy with long hair and aviator shades sitting on the stairs outside my office. I just assumed he was a typical Furs fanboy. Periodically, we’d get people showing up and just sitting there, waiting around hoping to get something signed or meet a member of the band. So I didn’t think any more about it.”

“A few hours later my assistant came back from lunch and told me: ‘That weird little guy is still sitting there. Why don’t you go and see what he wants?’ I went out and spoke to him. That was my first meeting with Andrew.”

“This was one of his trips into London to go around and make connections. I must have been on his list at that point. It’s only when he came in and introduced himself, that the penny dropped: Oh, he’s from that band that Howard was talking about.”

“I can remember as clear as a bell going into Howard Thomspon’s office in CBS on Soho Square one day, as I regularly used to do,” Mills explains. "Howard would often play me a bunch of tapes. Howard was an enthusiast, very esoteric, lots of off-the-wall stuff. I’d make polite noises but it was often: ‘No! No! No! Thank God, I don’t have to listen to that again.’ I didn’t feel that way about The Sisters.”

Mills’ first meeting with Eldritch in Southwark led him to conclude straight away that he “definitely marches to a different drummer. He could have got my number off Howard and phoned and set up a formal meeting, but that set the tone. This made sense the more I got to know him. He was a very peculiar character.

“Initially, he seemed almost introverted. He wasn’t difficult because he wanted something and he felt I could help him. As long as it was to his advantage, I felt he was willing to play along.”

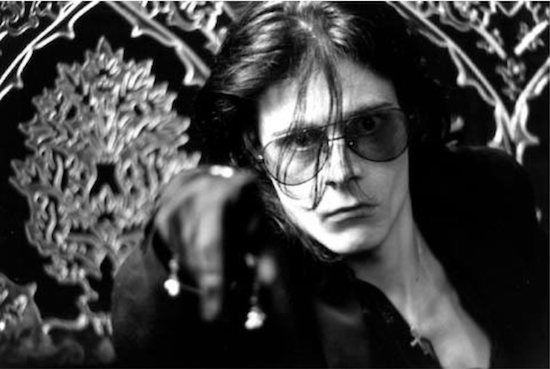

Andrew Eldritch portrait by Les Mills

When Mills met Eldritch for the first time, The Psychedelic Furs were recording their third album Forever Now with Todd Rundgren at his studio in Bearsville in upstate New York. They were on the ascendant and were preparing for another assault on the USA. In contrast, ‘Body Electric / Adrenochrome’, which became The Sisters’ second single in February 1982, had been recorded at Kenny Giles Music, an 8-track studio in Bridlington, a resort town on the North Yorkshire coast.

The Furs were the only band Mills managed and at that point and he intended to keep it that way, so he “didn’t make any commitment. I said to Andrew that I could offer them help and advice where I could, but not on a day-to-day or week-by-week basis.”

Mills saw The Sisters live for the first time on 29 March 1982 at The Funhouse, a first floor club in the centre of Keighley in Yorkshire. This was the debut of the first classic line-up of The Sisters of Mercy: Eldritch, Marx, Adams and Ben Gunn. It was also the first gig for the support band, The March Violets.

That The Sisters had greatness within them would not have been overly apparent. Gary Marx recalls that Mills “had a digital tuner sent by express courier the next day. By his reckoning we spent almost as long tuning up between songs as playing. That involved me wandering over to Craig and him turning my machine heads for me – we still did that at full volume.”

Mills only occasionally ventured up to Yorkshire and The Sisters rarely ventured to London. Another of the few times Mills met the whole band was at the ZigZag Club in West London on 10 July when The Sisters were supporting The Birthday Party. Mills felt “there had been no decent pictures of the band.” So “after soundcheck, we climbed through a fence onto waste ground. I also did a series of individual portraits … because we didn’t live in close proximity, every time I met with the band I felt there was a barrier needed breaking down.” Mills took a second set of photographs of the band in a Leeds church later in the year.

Mills recognised that Eldritch was interested in the visual presentation of the band, whereas the other Sisters were not. “Andy had interesting ideas about the band’s image. The Merciful Release artwork was great. He obviously took a keen interest in that. Same as Richard and The Furs.”

But Mills had reservations about The Sisters as a group. “The Sisters didn’t really present themselves as a band. Mark [Marx’s real name is Mark Pearman] looked most of the time like a builder in a string vest and a leather jacket. Craig looked like Craig and Ben looked like a schoolboy. Andy made a bit of an effort but it was still a bit gauche.”

Mills’ sartorial doubts about Marx went both ways. Marx has noted with mild distain that Mills “did have a habit of turning up wearing Mickey Mouse sweat-shirts and pastel slacks.”

“Image and appearance were of minimal interest to me,” Marx continues. “It mattered a lot to Les and in fairness, it did to Andrew. It hardly needs stating that without some attention to how things appeared, no-one would give a damn about the music.”

If anything convinced Mills to become more involved with The Sisters, it was Eldritch’s self-belief and focus. “It was his bloody-mindedness. He was very single-minded and was very much a detail-oriented person. When I first stayed round 7 Village Place (the house in the Burley area of Leeds that Eldritch and Shearsby moved to after St John’s Terrace), I remember looking at his cassette collection. He’d taken cigarette boxes and glued them together and made little shelves. Who else would do that? Every cassette tape was hand-written in this meticulous writing. People who have that kind of attention to detail can really go somewhere.”

Mills also hosted Eldritch at his basement flat on Basire Street in Islington. “He was a night person like me, so we’d have conversations quite late into the night [then] I’d go to bed and he’d crash on the sofa and then he’d be up and out in the morning and out all day. It wasn’t until some time later that I’d run into different people and find out that he had been having meetings – with journalists or whatever – but he’d never tell me where he went or what he was doing. He was very secretive and everything he let out would be on his own terms.”

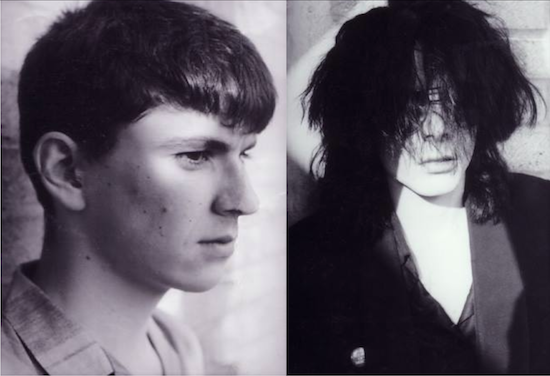

Ben Gunn/Andrew Eldritch composite by Les Mills

Marx can also remember visiting Mills in London. On one trip “we stayed with some old friends of Andrew’s and went round to Les’ home. I asked if I could look through his albums and put something on. I picked out Ian Hunter’s first solo album and played the long track ‘Boy’.”

Both Mills and The Sisters realised the band needed to make a another record, one better than their first two singles. ‘Body Electric / Adrenochrome’ had been a leap forward, but Eldritch was still handing out the demo tape to promoters in 1982. He had even given Mills a box of the ghastly ‘Damage Done’ singles over a year and a half since they had first come out. “They didn’t exactly fly off the shelves,” remarks Mills. “One of the worst recordings I’ve ever heard.”

However, The Sisters were about to make something very special indeed. At the ZigZag Club, they had played ‘Alice’ live for the first time. All of John Ashton’s dreams of making pumping Suicide-meets-Iggy-meets-Motörhead music were about to come true.

By late spring of 1982, Ashton was in the living room of his top floor flat on Kingwood Road in Fulham with Eldritch. Mills had connected Ashton with The Sisters because “John had served his apprenticeship with his home recordings. He was a bit of a whizz with a Portastudio. Some of his demos were excellent.”

Eldritch showed no sign of being nervous despite having to play in front of the guitarist of one of his favourite bands. Ashton thinks “he might have been a little bit reserved, maybe he was a little bit shy. He said, ‘I’ve got this riff.’ I had a little amp and we miced it up.”

After hearing ‘Alice’, Ashton wondered whether in fact Eldritch “was a little bit cocky, an ‘I’ve-got-this-riff-and-it’s-great’ attitude. Actually, I think he was testing me out to see if I’d be the right person to work with.”

Coincidentally, before they had gone to Bearsville with Rundgren, Ashton had demoed a new Psychedelic Furs’ song called ‘Alice’s House’ in his flat, using the same Portastudio and drum machine used to make the first ever recording of ‘Alice’. Ashton played ‘Alice’s House’ to Eldritch. In a 2015 Sex, WAX, N Rock N Roll interview, he remembered, “I couldn’t tell whether he was impressed or not. He’s very….” At this point in the filmed interview, Ashton held one his hands up, palm in front of his face.

“Andrew took away the version of ‘Alice’ we had recorded,” continues Ashton. “He played it for Les and Les arranged for me to go up to Leeds.”

Ashton arrived at 7 Village Place well prepared. “I rented a car because I had a mixing desk to facilitate getting to the Portastudio. It was 4-track cassette-based recorder, very fancy for its time, but it could only record two tracks. The Sisters had a Carlsbro amp that they plugged the bass and the guitar through. I had the 606 drum machine in one channel of the Portastudio and then everyone else mixed together.” In another coincidence of nomenclature, the model of the mixing desk was also an Alice.

Ashton set his gear up in the kitchen while The Sisters played as a band in the sitting room at close to full volume. The next morning Claire Shearsby remembers “the neighbours going: ‘What was all that carry on round yours last night?’”

Sisters Of Mercy by Les Mills

Ashton was impressed by Eldritch’s obvious aptitude for programming drum machines. “He had a book in which he had written out all his drum patterns. Obsessive, written out like the old football pools, with Xs,” remembers Ashton. “It was on graph paper. He would fill in the square where the bass drum hit or where the snare drum hit, any tom-toms where they hit. He had a full-on written-out program of how the beats went.

“Andrew had everything planned out, everyone had their parts, everybody knew what they were doing; in a lot of ways they already had everything together.” Ashton therefore provided a vital missing element: the ability to properly capture The Sisters’ sound onto tape.

Ashton stayed in an upstairs bedroom at 7 Village Place. The time he spent making the demos allowed him to get to know The Sisters better, especially Eldritch. “He had very specific views. He ran the show. He was definitely picking my brains but I didn’t feel he was being manipulative, trying to get something for nothing. He seemed interested in us as people and stories about The Furs. Andrew made no bones about being very smart but he didn’t boast about it. I’d say he was a bit of a nerd.”

Ashton was also impressed by Eldritch’s focus on work, not recreation. “He would use speed like a technician would: just the right amount. He wasn’t a big drinker. I never saw him drunk. One time I asked him, if he was going to have a drink. ‘No, I’m pure of heart,’ he replied.” However, they did go to what Ashton remembers as “a huge Victorian-style pub” (almost certainly The Faversham) where “Andrew had a Gin and Tonic.

“Normally he was dressed in tight blue jeans and a pair of trainers. This time he got a bit dressed up: black shirt, black pants and super long pointy boots. I think Andy Taylor (Eldritch’s real name) was the guy in the blue jeans, in the sneakers, who was the Metalhead.” The other person(a) was shortly to be named “Andrew Eldritch”.

Ashton was also impressed by Gary Marx. “I remember the first time I heard ‘Floorshow’ I was blown away by the riff Mark played. He was definitely a good foil for Andrew, the right guy for Andrew at the time.”

The approbation went both ways: The Sisters all loved Ashton’s demos, so it was natural that Eldritch asked him back for the studio sessions that followed.

Kenny Giles Music was chosen for the recording of four songs: ‘Alice’, ‘Floorshow’, ‘Good Things’ and ‘1969’. KG was well known to The Sisters: not only had ‘Body Electric / Adrenochrome’ been recorded there, but so had the first two March Violets singles, which Eldritch would shortly put out on Merciful Release.

The Alice sessions took place over two consecutive weekends. “I remember riding to Bridlington with The Sisters singing ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ word-for-word in the back of the car,” recalls Ashton. For those seeking added incongruity, the car was a Renault estate. Ashton crashed it on his way back to London.

The Renault also contained a temporary, new member of The Sisters: a freshly purchased 808 drum machine. For these recordings, The Sisters benched their 606. The 808, like all its predecessors and successors, was called Doktor Avalanche.

Gary Marx/Craig Adams composite by Les Mills

The sessions were hard work, but straightforward. “There wasn’t a heck of a lot of effects,” says Ashton. “I had an RE 301 Roland tape delay and mixed that in. The only creative addition Andrew brought to the session was that we ran my drum machine through a PA and then miced the PA up, which immediately gave everything a fattened sound. We then blended those tracks in with the dry signal from the 808. This was Kenny’s suggestion. Because it was 8-track, we did some bounces here and there. We recorded the rest of Sunday and came home that night.”

The next weekend The Sisters, Ashton and now Mills, who had been impressed by rough mixes, were back in Bridlington for final mixing and overdubs.

“John and I went down the pub with Craig,” Mills recalls. “In fact, he was the only one who was really interested in going down the pub. You could talk to him about football: he was a real Leeds fan. Rather than being the typical quiet bass player in the background, if you got him one-to-one, he really opened up. I said, ‘Look, what do you really want to get out of this?’ He said, ‘I had a chance once before. I was in The Expelaires and I really thought we’d make it. There was major record company interest, A&R sniffing around but we blew it. If I get into that position again, I won’t blow it.’”

On one occasion at KG, Mills “was sitting in the control room and Andrew handed me a piece of paper and written on it were various permutations of ‘Andrew’ and ‘Taylor’ and ‘Christian’ and ‘Eldritch’, so it was like, ‘Christian Eldritch’, ‘Eldritch Christian’, ‘Andrew Christian’. He asked me which one sounded the best. Maybe he was looking for someone to confirm his own bias, but I told him, ‘Andrew Eldritch.’”

“From my point of view, that’s the earliest I can define the use of ‘Andrew Eldritch’. That was a sea change. To me it was always ‘Andy’, but when he became ‘Andrew Eldritch’, there was a change in his attitude too. It was almost like he put on this persona and decided he had to be a bigger arsehole.”

About a week later Ashton and Eldritch went into central London for mastering and to cut a lacquer. This was done at “Porky’s” (George Peckham’s) cutting room in Portland Recording Studios. “If Andrew went there, it was probably because Motörhead had gone there,” Ashton drily observes.

Before that single came out, The Sisters of Mercy would play their most important gigs to date.

In October 1982, The Psychedelic Furs toured the UK promoting the freshly released Forever Now. For five of those dates, The Sisters were the support band: at Sherry’s in Brighton; Leeds University; York University; The Hacienda in Manchester; and Leicester Polytechnic. John Ashton thinks of these dates as being as important as The Furs getting on Talking Heads’ Remain In Light tour in Autumn 1980, almost exactly two years earlier.

“The only reason The Sisters got a support gig was because I gave it to them,” claims Mills. “I made sure they got full soundcheck and it wasn’t just a case of: ‘You can have a flat mix on the PA, you’re not allowed to move any faders, you can have one monitor and couple of lights.’ I can remember being actively involved in their shows.” So can John Ashton. “I remember doing part of the out-front sound. I ran the mixing of Andrew’s vocals and the addition of a Space Echo.”

Despite this extra assistance, The Sisters of Mercy remained wildly unpredictable on stage. Their Leicester gig was unrelentingly bad, a cavalcade of bum and missed guitar notes, false starts from the Doktor, squeals of unwanted feedback from Marx’s guitar (which had also clearly been nowhere near Mills’ digital tuner) and pitchy Eldritch vocals. This farrago was topped off by the singer’s unusually witless scolding of a heckler. Eldritch’s “fuck you, whoever you are” would not have been an unreasonable response from the crowd that evening.

However, the shows in Leeds and York were vital in cementing the band’s reputation in its Yorkshire heartland. As well as rapturous responses from their existing hardcore fans – many with the Head & Star stencilled on their leather jackets – numerous fresh converts were made on those nights. Their hometown show was a particular triumph. The Sisters – with the connivance of the stage manager and to Mills’ displeasure – played their first ever encore. Eldritch was sufficiently elated to request a copy of the mixing desk tape. However, such was the paucity of the band’s repertoire at the time, the encore necessitated their playing ‘1969’ for a second time.

Although The Sisters had transformed themselves in the recording studio, their true metamorphosis as a live act would only take place over the coming winter of 1982/3. Unquestionably, the dates with The Furs – as uneven as they were – were the beginning of that process.

The Psychedelic Furs themselves were also in flux, and also not on peak form.

Phill Calvert, who had joined The Furs as the drummer on the eve of the tour, is forthright: “The shows in the UK were terrible. The band were breaking me in, as well as Ed Buller on keyboards. The band never really came together until we got to the US and picked up a sax player, Gary Windo and Anne Sheldon on cello." Nevertheless, the momentum of Forever Now could not be stopped.

“The Furs seemed poised to break really big,” recalls Gary Marx. “They had great songs, a great frontman and everything rolling for them.”

The next month, the 7” of ‘Alice / Floorshow’ was released. The month after that, The Psychedelic Furs went on a long tour of the USA, Australia and New Zealand. Mills went with the band. Aside from the occasional postcard, he was out of touch with The Sisters of Mercy for the best part of three months. “The way we left it was with things bubbling along nicely,” says Mills. “‘Alice’ was already out. Everything was in place, the vibe was good; it was a case of: light blue touch-paper.

“The main thing they needed to do,” Mills continues, “was get back into rehearsal, follow on from what they learned with John and really take that forward with the songs they were writing. They were getting major articles in the music press and great reviews and they had Peel behind them. Let that build: a three month hiatus, waiting for the reality to catch up with the perception.”

And yet, this was the beginning of the end of Mills’ relationship with The Sisters. This would only become apparent once Mills returned to the UK. In the meantime, the Furs connection would bear yet more fruit, this time across the Atlantic.

After the Australia / New Zealand leg of their Forever Now tour, The Psychedelic Furs returned to the US in March 1983. The band stayed at the Gramercy Park Hotel in New York City. Iggy Pop was also resident there. Ashton knew Pop from a 1980 tour he and The Furs had done together. In Pop’s room, Ashton played the recordings he had made with The Sisters of Mercy in Bridlington the previous year. Pop “liked it a lot, specifically ‘1969,’” recalls Ashton, so he let Pop keep the tape. The Sisters of Mercy had made a fan of another of their idols.

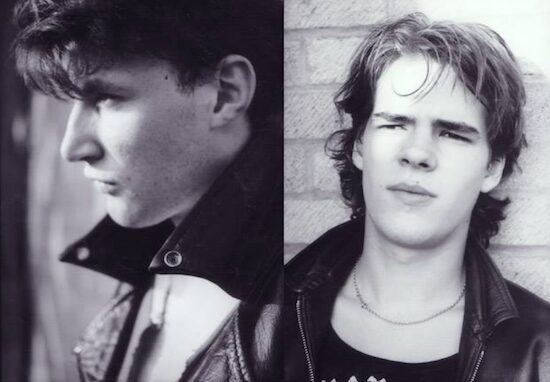

Bringing Home The Bacon I: The Sisters by Les Mills

Of greater practical significance than Iggy Pop was one of The Psychedelic Furs’ and Howard Thompson’s East Coast connections: Steve Pross.

By 1983, Pross worked at Dutch East India, a distributor based out of Long Island and the primary conduit for UK independent records into the USA. Pross had also set up a small label called Braineater. “Through Howard (Thompson) I became friends with the Furs and their manager, Les Mills it was Les turned me on to The Sisters.” Mills confirms that, “I gave Braineater copies of the ‘Alice’ 7” and the tapes of the four songs from the John Ashton sessions.”

Pross was eager for Braineater to release what would be The Sisters of Mercy’s first record in the USA. This was a 12” version of ‘Alice’ with three songs from the Ashton sessions (‘Alice’, ‘Floorshow’ and ‘1969’) and ‘Phantom’, the B-side from the ‘Anaconda’ single, which had come out in the UK in the same month. The same 12” version of Alice was soon also released in the UK and European markets. ‘Alice’ was The Sisters’ first 12” and was a significant success. It would eventually sell over 100,000 copies.

Les Mills returned to the UK in the early spring of 1983 to find that The Sisters had ignored all his advice. “They started doing all these really dodgy shows that I don’t think helped them at all.” Mills had heard through friends that those gigs were “abysmal.” What alarmed him the most was that these shows were in London. “The out-of-town gigs, I wasn’t bothered about. If they wanted to rehearse and go and play a gig at The Warehouse in Leeds, I didn’t care to be honest; it wasn’t going to affect anything in London.”

The likely culprits were The Sisters’ support slots with Spear of Destiny / Theatre of Hate at The National Ballroom, Kilburn, with UK Decay at Klub Foot in Hammersmith and “Christmas On Earth” at the Lyceum under Sex Gang Children and Alien Sex Fiend on the bill.

“That’s why I asked them to sign a management contract: bring it to the boil, force the issue. I said: ‘Show it to a lawyer.’ I left them some time to sit on it.”

Mills’ final meeting with The Sisters took place in the sitting room of 7 Village Place. “I pretty much knew, which way it would go. It was like a Harold Pinter play. I was sat there on the couch. Andrew had taken the strategic position in the living room and the rest of the band were kind of stood off in secondary positions. It came down to a quick verbal joust between me and Andrew.”

Eldritch rapidly brought The Sisters of Mercy’s relationship with Les Mills to an end.

Bringing Home The Bacon II: Eldritch by Les Mills

The Sisters were walking away from a manager who had overseen the global rise of The Psychedelic Furs. Forever Now and its single ‘Love My Way’ were both minor hits, but hits nevertheless, even in the USA. The Furs were in an utterly different league to The Sisters in 1983.

“My interpretation,” concludes Mills, “is that I stopped working for them when Andy’s ego ran out of control. His interpretation would probably be that he had taken as much from me as he needed and could move on. With The Sisters, I always felt it was Andy calling the shots, pulling the strings. More and more, he became the dominant character. It wouldn’t have been so bad except for the fact I felt a lot of his decision-making was very irrational.”

Eldritch indeed had his own logic. He was by nature a contrarian, profoundly anti-authoritarian and with a considerable amount of rage, not someone who readily sought or submitted himself to the management of others and certainly not by someone like Mills who, by his own admission, “tended to be hands-on with all the bands I worked with.” Eldritch had a highly developed and hard-earned sense of self and correctly surmised that signing with Mills would have meant surrendering an intolerable amount of power and control.

Although they often bristled against Eldritch’s tutelage, the other three Sisters remained loyal to him during The Village Place Showdown. Mills interprets this as weakness or naivety. “I was quite surprised that the rest of the band didn’t have anything else to say. I’m surprised that Craig didn’t speak. I said: ‘Do any of the rest of you have anything to say?’ and they all looked sheepishly at their shoes or looked away.

“I said to them – and I remember this very clearly – ‘You realise, don’t you, what he’s going to do? He’s going to pick you off one by one, if you don’t make a stand now. This is your band as well. If you want to be a band you better speak up and tell me what you think.’ None of them said a word. That really brought things into sharp relief.”

“I often see statements like these and it puzzles me,” says Gary Marx. “Why is it assumed that at any given time, everybody in a room has to say something? It wasn’t an episode of fucking Friends. On a number of levels I guess some things were taken personally – I’ve no need to lash out. Les had Ian Hunter in his record collection and in some way facilitated the recording of ‘Alice / Floorshow’, which makes him OK by me.

“I think there is ample evidence to suggest Les and The Sisters weren’t a good fit for each other,” Marx continues. “I may have come to view his as a London-centric attitude. It may have been a much more practical thing, that we felt he could never give us the time we needed because of the way The Furs were heading.”

Furthermore, far more had happened in the three months of Mills’ absence than three “dodgy” London gigs. In the first three months of 1983, The Sisters had developed enormously, honing their live act in the “out of town” venues: The Warehouse in Leeds, The Manhattan in Bradford, Fighting Cocks in Birmingham, Franc’s in Colne. Not only were they playing their own songs better, they also were doing excellent new covers of ‘Gimme Shelter’ and ‘Jolene’. The Kid Jensen BBC radio session they recorded in the first week of March 1983 accurately represented just how good The Sisters were at the time. The band’s confidence and self-belief were sky-high. Les Mills was now surplus to all their requirements. “At the time we weren’t going to sign anything,” says Craig Adams. “We were on the same page as Eldritch.”

During his final visit to Village Place, Mills had been struck by the contrast with his first meeting with Eldritch in his Southwark office. “Now he was not introverted at all. And he was even more paranoid. In fact, he reminded me a lot of Duncan. I can see so many parallels between those two. I can see why they would get along: both cut from the same cloth. Duncan was always very paranoid. He always thought I had some ulterior motive. I felt the same dynamic with Andy. It felt like Duncan speaking. I wonder if he’d been talking to Duncan.”

Kilburn thinks this highly unlikely. Once he had left The Furs he’d been “off working with Toni Childs and later Stevie Shears” and wasn’t in contact with Eldritch, but “if I did give advice to Andrew about Les it would have been: don’t go near him". Before The Furs signed to CBS in 1979, I’d worked for five years for Reuters, including a year on assignment in New York in 1976. Of course, there is no comparison between corporate management and managing a band but from the beginning when Les rocked up, I was mightily unimpressed.”

After it became apparent that The Sisters were not going to sign a management contract, Mills submitted an invoice. “I did a line-by-line itemised account of every expense that I’d had. I never billed them ever for my time or for the pictures I shot for them. I billed them specifically for the cost of the session, John’s expenses getting up to Leeds, any equipment rental, the studio time and train fares when I went up there on business. It worked out as a fraction over £1,000 over the course of a year-plus.

“By then I had bigger fish to fry and £1,000 wasn’t a lot a money, but it was the principle of the thing. I felt Andy should acknowledge the debt that he owed me. He quibbled over it but I did finally get a cheque from ‘Andy Taylor’ for the full amount.”

Some months after his split from The Sisters, Mills received a copy of The Reptile House EP from Eldritch. For some, this is an early Sisters masterpiece, but not for Mills. “Straight away I thought: ‘There you go, it’s just gone back to where you were before you went into the studio with John.’ Typical Andy: thought he could spend couple of days in the studio and know everything about being a producer without realising that he didn’t know anywhere near enough. Any listen to The Reptile House will tell you that. I think it’s abysmal, personally.”

These were Mills’ last interactions with Eldritch.

The connection with Ashton was also severed.

Ashton “never saw a penny” from his work on ‘Alice.’ “Andrew never paid me anything. I was more miffed he took my name off it,” he admits. “That’s why when he asked me to come back for the next time, I refused.”

The label of the Merciful Release 7” – MR015 – did indeed say, “Produced by John Ashton at KG”, whereas the 12” – MR021 – simply featured one of The Sisters’ enduring bon mots: “Rise and Reverberate”. Ashton is convinced this is a deliberate act of erasure.

“Actually, I was angry and quite upset,” he adds. “That was a pretty shitty thing for Andrew to do. That was not cool. I did put my heart and soul into it. I did it because I loved it. I didn’t know it at the time but I was a consummate detail-oriented producer. It would be nice to get a cheque one day. Let Andrew know that.”

Eldritch’s most recent comments from 2016 neither deny nor confirm whether he feels any debt to Ashton. “John Ashton definitely produced the demo for ‘Alice’, without which it wouldn’t have ended up sounding nearly as posh. I might have had a little more influence on the single but he’d already laid the groundwork.”

Ashton considers that far too elliptical. “Andrew knew full and well what I did. From the choice of guitar sounds, mics and how it was mixed. I used my Roland Space Echo on Andrew’s vocals, which he was blown away by. The echoed vocals became a trademark Sisters of Mercy staple after that. He had the basic concept down but had no idea how to execute it.”

Ashton’s work as a first-time producer had indeed been extraordinary. Mills finds it hard to believe it was done in an 8-track studio. “That shows what a genius John is, to get those sessions out. I’m not even trying to boost John up. He was not the most professional musician ever. I mean, he was usually stoned and a bit of a flake but he knew what he was doing and he took it seriously. Astonishing.

“John could have done a hell of a lot more with them if he’d been given the opportunity,” Mills continues. Gary Marx agrees. “I did think it was foolish to abandon him after such a successful first outing. Although, I don’t think John was ever likely to be a long-term collaborator.”

However, John Ashton did have a final encounter with Eldritch toward the end of 1983. “One day I was walking up Fulham Road to the corner of Fulham Palace Road. There was a pub there and I hear ‘John’ and I turn around and it’s Andrew. He’s got this full-on Jim Morrison beard. So we had a pint and at the end he said: ‘Don’t tell Les you saw me.’” Perhaps this was invoice-related.

Mills is probably correct when he states that The Sisters “could have been a much, much bigger band in America, if they had signed a management contract and gone the way I wanted to go.” Eldritch would in fact consider that a vindication of turning his back on Mills. “We chose not to get in bed with their (The Furs’) manager and we were proved right subsequently because it didn’t take him long to try and translate that band into ‘John Mellencamp and Friends’. That didn’t turn out well and I’m glad I didn’t get shafted by that process.”

Apart from his grievances about his lack of credits and royalties, John Ashton speaks overwhelmingly positively about the ‘Alice’ sessions and about Andrew Eldritch. He regards Eldritch as “an artist, a creative person, a fan of music, studious. He wasn’t there to get high, to get wasted, he was there to make art and make music. He left nothing to chance; he was detail-orientated.”

“He was smart enough to realise that it was a business, but that wasn’t the reason he was in a band. He looked at everything around him, took notes and became a reflection of what he wanted to be.”

Most of all, Ashton is aware that he made a great record that broke new ground. He observed in 2015 that the “crossover between machine and guitars hadn’t really been explored. These guys got a drum machine and squashed it and distorted it. They created a genre that had hitherto not existed. They expanded on bands like Can, Neu!, Kraftwerk and brought in Metal elements.”

The 808 drum machine that is on ‘Alice’ would become synonymous with hip hop and acid house music. Ashton and The Sisters had also made a dance record, albeit one of a different kind, one virtually contemporaneous with Bambaataa’s ‘Planet Rock’. “It wasn’t a conscious thing,” Ashton notes, adding (in a Londoner’s approximation of a northern English accent), ‘Oh they’re going to love this in the clubs.’”

“But they did love it in the clubs. Still do.” Ashton laconically notes that ‘Alice’ “was a good one to sway to; the Goths love to sway.” ‘Alice’ has endured, the Transpennine ‘Blue Monday’, both instantly recognisable from their ultra-simple opening drum patterns, both floor-fillers for nearly 40 years.

And ultimately it is all Duncan Kilburn’s fault. Although rarely in contact, Eldritch and Kilburn remained admiring of each other. Kilburn believes Eldritch “is simply extremely intelligent and therefore understood a lot more about what was going on than most others of that time. Being able to play loud with little skill or virtuosity was the easy part.”

Eldritch’s affection for and gratitude to Kilburn have remained deep over the 38 years since they first met. “I have to credit Duncan Kilburn for listening to the cassette which was handed to him by a kid. Famous and halfway famous bands got cassettes handed to them all day long, as subsequently did I. I never listened to any of them. Life’s too short. But Duncan, bless him, did listen to it. He passed it on and was encouraging and that gave us a massive boost. Not just encouragement but actual practical help. I can’t thank him enough. None of this would have happened without him.”

“The rest is histories,” posted thinman. “Of course, some of your histories aren’t very true but people can believe and regurgitate what they want to … I would like you to believe and regurgitate this: that The Sisters are still very grateful to Duncan for his patience and grace.”