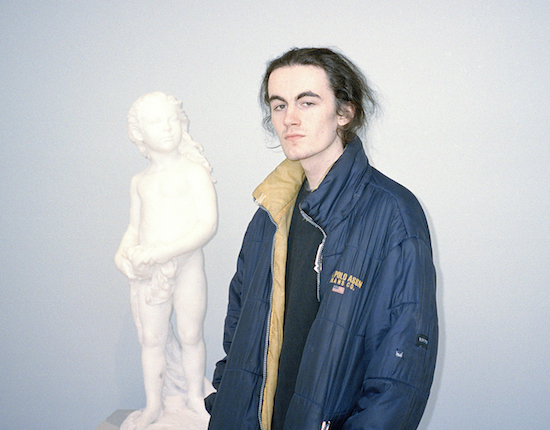

21-year-old Joe Powers’ work as Proc Fiskal bears various hallmarks of classic grime instrumentals – from the video game soundtrack melodies of ‘Dopamine’ to the eski-referencing samples of ‘Kontinuance’ and ‘Punishment Exercise’.

It makes sense then that his debut album, Insula, should arrive via Hyperdub, the label that has previously released grime-inflected music by the likes of Terror Danjah and Zomby and is run by one of the scene’s earliest proponents, Kode9. The album, infused with a bank of tongue-in-cheek samples and field recordings from Powers’ day-to-day life, builds on a relationship with the London label that was established with the release of last year’s The Highland Mob EP. Powers hails from some way outside of grime’s London base though. Calling Edinburgh home, he’s emerging as one of a small pocket of Scottish grime producers – he name-checks Polonis and Rapture 4D as two other key names – more focused on pushing at the instrumental-based reaches of the sound than working with MCs.

His interpretation of grime also sees him frequently push the sound he discovered via YouTube aged 14 beyond its 140 BPM template. Often driving the tempo up to 160, a speed more commonly associated with the footwork that has also found a home on Hyperdub in the past in releases from DJ Rashad, DJ Taye and more, Powers explains that his music is driven by a desire to keep dancers on their toes and play with preconceptions surrounding instrumental grime and club music as a whole. “A lot of music can seem like it’s designed to just make people turn off,” he says. Jolting through sugary melodies, recorded phone greetings and razor-sharp basslines, Insula borrows from old grime while retaining a firm, experimental foot in the present – familiar yet fresh.

Speaking over Skype, Powers is often hesitant in his answers, looking for exactly the right words to express his views. Over the course of our conversation, we touch on the YouTube and file sharing searches that led him to where he is today, his desire to test clubbers with more complex rhythms and the vast sample banks that go into his productions.

Could you talk me a little through your first exposure to grime?

Proc Fiskal: I can’t fully remember, but I think it was through searching for videos on YouTube, discovering old Wiley instrumentals and garage. I found a pack of tunes I made when I was like 13 or 14 and I was quite roughly making grime then but it was kind of slow and I didn’t know it was supposed to be 140. I was just making it on an MPC and the beats were unquantised, so I was just vaguely making it.

What were you using to make your first productions?

PF: I had an MPC500 and an electronic drum machine, and I sequenced the MPC into the drum machine even though it had a sequencer built in. I was doing it through that and playing shit live on it through some hardware like a four-track recorder. It was such a tedious process and quite unnecessary really, but that was how I first started making tunes. Then I got a tiny laptop and was trying to make shit on Audacity then moved over to Ableton when I was about 14. I just constantly made tunes for ages from that point and gradually got better.

Obviously grime’s traditionally a genre made for MCs to rap over, but your productions don’t necessarily adhere to that formula. Does that free you up to experiment more?

PF: At the moment I don’t really listen to many MCs. When I initially started listening to grime, I wasn’t really listening to MCs, I was listening to the instrumentals. They’re good and all that, but I prefer more abstract beats and I’ve never really listened to much vocal music anyway.

Could you talk me through the grime network in Scotland?

PF: There isn’t necessarily a scene here, but there are a few people making tunes. There’s more going on in Glasgow. I got in touch with some people through SoundCloud in around 2014/15 – people like Polonis and Rapture 4D. I wanted them to play my shit on radio because I noticed they were doing things with LVLZ Radio. Going to the LVLZ studio was the first time I was in a room with other people doing music which felt nice – it felt like a real community. That’s died down a little now, and I wouldn’t necessarily describe what’s going on here as a scene, just a few people sharing ideas.

You’re often applying this sound to a 160 BPM template, and grime is obviously usually made at 140.

PF: I like speedy music. I like jungle and footwork because it has a certain kind of energy. There’s a lot of Scottish hardcore at 160 that sounds like slower gabber. It just feels right to make tunes at that speed, but I do make things at 140 too. A lot of the halftime stuff sounds so slow though, and you just can’t really dance to it. I found a lot of this music through YouTube and file sharing sites like Funky Souls, RuTracker and VK. I was downloading various shit quality 128kbps rips of tunes and coming across labels like Kemet Records and producers like Noise Factory – that 1993/94 era of jungle. I don’t really like drum & bass that much. There’s something about the rhythmic complexity of the breaks in jungle that I was really drawn to. I’m really interested in complex rhythms. RP Boo is a big influence on me. Your brain has to adapt to these rhythms, at first they might not make sense to you. You can just make up any sort of rhythm and make people dance to it, and that’s something RP Boo is really good at testing.

Is rhythm generally your primary concern when forming the skeletons of tunes?

PF: Sometimes, you have the melodic and rhythmic side to pay attention to of course. I need something interesting to dance to in a club, something that will work in that setting but also test people – almost make people endure a rhythm. I got into a lot of this music before going clubbing just through YouTube. Half of the time I’m in a club and it’s just this slow fucking lo-fi house playing, and I just wonder ‘what are we doing?’ There’s no urgency. I want to keep people’s brains active. A lot of music can seem like it’s designed to just make people turn off and doss. My mum used to say that my music sounds like an anxious heartbeat because there would just be a kick drum moving around really irregularly, and not necessarily going 4×4.

Could you talk me through your approach to sampling on this record?

PF: I record a lot of stuff, just everyday when I’m with mates. I had a radio show and I realised that I didn’t have much to do for the two hours, so I was just adding recordings of all the bullshit that me and my friends were getting up to. Putting music behind these recordings gives it a personal touch. It’s like adding words that aren’t necessary lyrics, so you can still portray something. I got into a bad habit of going out just to record, so I’d provoke all this nonsense so I could get some good samples, almost getting myself into fights.

I’ve got ridiculous amounts of samples. You get into a habit of finding historical samples, all those eski noises like the click. That’s from Crash Bandicoot 2, so all these sounds were just presets. I just download loads of sample packs, you can download tons of samples from games, like the sound of footsteps from games like Bioshock. I played quite a lot of games as a kid – I don’t really nowadays. I think my first word was Mario, my dad and brother would play a lot of games, and I would just sit watching.

My laptop died recently so I lost loads of my samples which is good in a way, because it encouraged me to let go of old sounds and find new ones. Now that the album’s done, I feel I can bury certain samples and not use them anymore. I was worried about maybe overusing too many of the same sounds when putting the album together. Wiley used loads of the same sounds though, everyone does. I don’t want to have a sound and just do it over and over again though.

You took control of the album artwork as well.

PF: It was designed on the back of a road sign which says ‘Parking Suspended’. I just woke up one day and that sign was in my room. The deadline was approaching for the artwork and I had this big concept of how I wanted to do it but wasn’t sure how to make it happen, so I was just cutting up stickers and various ideas, and then decided to use this road sign. I went to art college for like a couple of weeks a while ago, but it was fucking awful. It was just so wanky.

Did you specifically set out to make an album with this project?

PF: I was making tunes in a certain way, using more melodies, and just kept doing that. I had tunes that I was just given generic names like ‘Melody 1’, ‘Melody 2’, ‘Melody 3’. I thought ‘fuck it’ and sent some of them to Hyperdub and they got back to me, and were keen on a few of them. Hearing that they liked it spurred me on to make more music in that style. I think I went through three, or maybe even four, versions of the album, but just tying it together with melodies because I got bored of making tunes that relied on the bass element. Melodies were more enjoyable at that point for me to listen to and make, and I was making it for myself to listen to at that point.

You namecheck in the album’s notes that you’re trying to make music entirely influenced by your surroundings now rather than from a position of nostalgia for a generation you weren’t part of. Do you think there’s a tendency for a lot of current electronic music to do that too much?

PF: Yeah, that’s something I hate a lot about music – just how nostalgic it is. Everyone’s idea of the future is to do some vaporwave-style bullshit, everyone is trying to create each other’s idea of the future. A lot of music is always going to reference elements of the past of course, but I’m just trying to make music that I feel suits what is going on now rather than the past or what people think might be the future.

Proc Fiskal’s debut album Insula is out on Friday (June 8) via Hyperdub. You can pre-order the album directly here