When Peter Gabriel left Genesis he blamed his vegetable patch. The English prog rock band had just broken through to the mainstream with sprawling concept album The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway and were standing on the verge of international superstardom but the enigmatic frontman announced that he’d had enough. While it was true that Gabriel had been spending a lot of time tending to his cabbages in the garden of his small cottage in the Cotswolds, it was other, more serious matters of nurturing that required his attention. In 1974 his daughter Anna-Marie was born breech and then developed a serious infection, which left her fighting for life during her first six months. So despite being massively in debt and just about to hit paydirt, he ditched his career to become a family man and start creatively from scratch.

As well as being a young dad, the next two years were spent reading about world religion, art and philosophy, widening his knowledge of various forms of African, Asian and South American music and becoming an early devotee of punk and post punk. (If the official line was that punk was the enemy of prog rock, then no one told him – he was an attendee at several pre-fame Sex Pistols shows.) And while none of this neophilia, experimentation and intellectual endeavour revealed itself in the first song he wrote post Genesis, the apres-Hippy anthem, ‘Solsbury Hill’ – it soon would on a series of fantastic albums, including the monumental Peter Gabriel (aka Three aka Melt) and the world conquering So. This intense, initial period of change and growth was bookended by two more births in 1976: that of his solo career and that of his second daughter, Melanie.

Melanie Gabriel has performed backing vocal duties in her father’s band for some time now and is one of a dizzying cast of musicians who appear on his latest album New Blood – a collection of his songs performed with an orchestra. While the tracks are taken from the length of his career, this is no greatest hits reworked in bombastic, West End musical style. For example there is no ‘Sledgehammer’, no ‘Shock The Monkey’, no ‘Steam’, no ‘Games Without Frontiers’. Instead we have the darker and denser work from his back catalogue; ‘Intruder’, ‘San Jacinto’, ‘Darkness’ and ‘Red Rain’ arranged to form an intrinsic narrative of their own. The admirably restrained scoring was completed by conductor and arranger John Metcalfe working under Gabriel’s instructions. The pair had worked together on the recent Scratch My Back album which saw the singer tackle other people’s songs – but this album, apparently an afterthought, is the much more satisfying of the pair.

Before the interview I’m shown a 3D film of the New Blood project in EMI’s offices. There’s something very chilling indeed about seeing a 10" tall Don Logan from Sexy Beast walking out of a flatscreen TV and across a glass topped table, singing ‘Intruder’ a song about a rapist transvestite breaking into your house. To borrow another film simile, it’s like the exact opposite of a holographic Princess Leia saying: "Help me Obi-Wan, you’re my only hope."

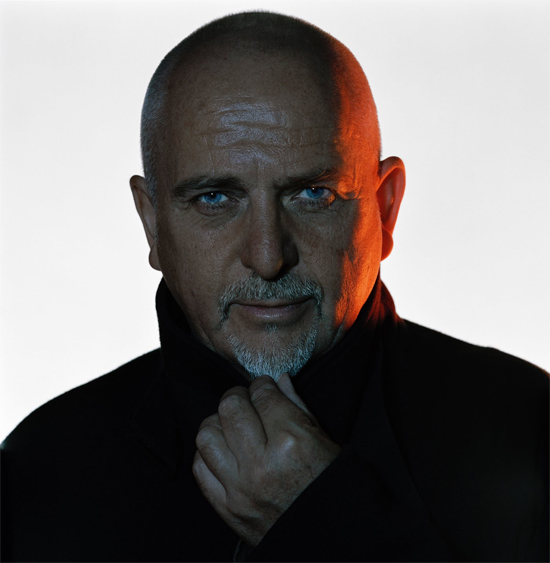

Thankfully Peter Gabriel in person however is urbane, charming, funny and very, very tall.

Had you always planned to do New Blood or was it inspired by Scratch My Back?

Peter Gabriel: It happened because of Scratch My Back. When we took it out on the road I realised that there wasn’t enough material [for a full set] so I had to come up with something else. So I thought, ‘Well, I’ve got an orchestra here, I might as well have a go at some of my stuff and see what works.’ We tried one or two things and it seemed to work. ‘Rhythm of the Heat’ particularly. We had this idea of taking the drums from the end of the original and translating them to orchestral music and John Metcalfe, who is a brilliant arranger, did a fantastic job. We really felt as if we’d come up with something that we hadn’t heard before. And what we really didn’t want to do was the usual thing of having a rock band with an orchestra, so we took away the guitars, drums and bass and just worked with the colours of the orchestra.

Songs like ‘Intruder’ and ‘Red Rain’ were already very dramatic in their original form. You must have been aware that without a sensitive orchestral reinterpretation, some of these songs could have come across as quite bombastic.

PG: Yeah. I think that’s a risk. You can suddenly get grandiose with an orchestra, so I think there was an intention to stay away from the worst of that but at the same time allow it to really flourish when it felt that it was right. John is very tasteful so he’s more of a minimalist than… a West End musical producer.

With age you’ve developed a grain to your voice which certainly suits the lower and middle parts to what you’re singing but then you hit some amazingly high notes as well. Were you worried about tackling something of this range?

PG: Yeah, well I cheat on occasion. I used falsetto rather than full voice in some bits. There’s a particular high note on ‘Don’t Give Up’. But I think my voice has probably dropped a tone [over the years] and most of the songs that have high notes I’ve had to lower a tone for the set. On the other hand you get given some notes down the bottom end. You only have to look at people like Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen, who have done more with their old voice than they were able to do with their youthful voice.

So the album opens with ‘Rhythm Of The Heat’, which I believe was originally called ‘Jung In Africa’ after this amazing story about Karl Jung seeking to experience the sublime among the tribes people of Ethiopia. When he actually came face to face with a ritual ceremony one night, he became extremely scared and attempted to frighten them off by shouting and throwing cigarettes at them. I was wondering if you saw any of this dichotomy in yourself, the idea of a person being very exploratory but still very worried about what they might discover?

PG: Yeah. Oh yeah. There were parallels with me exploring African music. I love the idea of this guy who shaped a lot of the way we think in the West, who lives in his head and in his dreams suddenly getting sucked into this thing that he can’t avoid where he has to let go of control completely and feels that he has become possessed in a way, not by a devil but by this thing which is bigger than him and I think there is a bit of that sense of the European exploring African music.

Another dichotomy I’ve read about regarding you is that you’re someone who freely chases altered states of mind whether by hanging upside down by your ankles, or meditating, or spending time in flotation tanks or by reading esoteric works but contrary to popular belief, you don’t take drugs.

PG: No. The only drug I was interested in was LSD but I look at my nine-year-old son now and he gets scared shitless by his dreams and nightmares and I think I was the same as a young man – I didn’t really want to amplify what was already vivid to me. But I was curious and I’ve got drunk, I’ve smoked dope but not regularly. One time I was trying to write lyrics and I was stuck. The road crew had baked a hash cake and I thought that might help. I had this empty page staring at me and I thought, ‘What the fuck do I do?’ I started eating it and I was thinking, ‘This just doesn’t do anything.’ So then I ate all of it. Ha ha ha. Then I thought, ‘It’s still not doing anything, I don’t understand it.’ So I sat down at my desk and there was this surge of silver metal that came shooting up my spine and exploded in the front of my head and I started hallucinating. I was absolutely certain I was going to die. I had a cassette recorder with me for lyrics and I thought, ‘Ok, well I’ll keep this with me to record my last words.’ I started heading home to where Jill [his wife at the time] and the kids were. It was about a mile across some fields and a stream. If you listen to the tape now you can hear me fall into the stream and start swearing. I was trying to get my last words down but then I fell in a bramble bush. Eventually I got home and my wife saw me covered in blood and scratches and mud, she thought I’d been in a car crash but still holding onto a tape recorder for some reason.

In between all the tumbles, did you have any words of wisdom for yourself?

PG: Yes! I realised that life was four video machines slightly out of sync. [laughs] And that I was the only person who was going to be given this information.

Just say no!

PG: [laughs] Yes.

Early on the album there is ‘San Jacinto’ which very much suits the orchestral reworking. It’s a song that’s very rich in imagery and the song, as I understand it, is about the contrast between the initiation ceremony of a Native American and a Ballardian view of the American leisure resort Palm Springs. Can you tell me a bit about the chance encounter that inspired this song.

PG: We were in the Mid West somewhere on tour. We used to drive ourselves and we’d just checked into a motel after a gig. I got chatting to the porter who turned out to be Apache. He said, ‘I’m sorry, my mind isn’t really on the job tonight because someone phoned and told me that my apartment’s burning down. I don’t really care about it but my cat’s in there.’ I said, ‘Why aren’t you there?’ He said he was working and didn’t have any means of getting there, so I drove him. And true enough, when we got there he wasn’t bothered about any of his things, just his cat, which really impressed me. His neighbour had his pet, so that was OK. So then we sat up most of the night and he told me about the initiation into being an Apache brave. There was a warrant out for his arrest on a trumped up murder charge so he’d had to leave Arizona but back when he lived there, each of them at the age of 14 were taken up a mountain with the medicine man who had a Rattlesnake. Once they got to the top, he would take the rattlesnake out and get it to bite the boy, who would then be left to have his visions. If he made it back down to the village – as most of them did – he was a brave and if he didn’t he was dead. And so many cultures seem to have that custom where the young man, traditionally at least, is forced to face death in some way. And I actually think that in most cultures where death is ever present, they manage to live life more fully as a result. Later when we were driving through Palm Springs and Arizona we saw the way that the Native American country had been turned into discos and restaurants. There wasn’t a whole lot of respect for the real culture there just the commercial aspect of it. When I started climbing up San Jacinto, I saw these ribbons on the trees and I knew that this was part of an initiation process. This became my little vehicle. I didn’t have any visions myself but I had the fantasy of what it might be like and that became the focal point. San Jacinto is a snow capped mountain surrounded by desert and it was once all Native American land.

I wonder if any of the young Native Americans came to the realisation that life was actually four videos running slightly out of sync after getting bitten by a rattlesnake.

PG: Ha ha ha. Yeah.

So we’ve only been talking for a short amount of time and we’ve already talked about native Ethiopian and Apache civilization and I guess that anyone who has even a passing knowledge about you, knows that you have these interests in ancient and distant cultures but at the same time you’re also interested in very cutting edge technology and this isn’t a new thing. Didn’t it look at one point in the late 1970s that you were going to be the first professional musician in space?

PG: Yeah, that was a strange story. I had these fan letters from a guy involved in the Stanford Research Institute, who used to run lots of interesting programmes. One of them involved experiments with extra sensory perception [ESP] when the US Government were worried that the Russians were attempting to "will" people to death and to discover secrets by remote viewing. So they thought they’d better spend some money on ESP research. This guy said you’d really like my boss Peter Schwartz, who was then involved in running a thing called the Global Business Network. He was a trained astrophysicist who had become a research consultant. NASA had this programme to produce a film to try and popularize the idea of the Space Shuttle and space travel, and all of this was being funded by a very wealthy Iranian. They were going to train two teams and the team who made it would include a writer, a musician, a poet and a painter and we were going to go up in the Shuttle and then write, sing or paint about our experiences. He asked if I would be interested, and I said, ‘Yeah.’ Who wouldn’t be? But then when the Shah was deposed in Iran this guy’s money was seized and the project was shelved. So my dreams of becoming Britain’s first astronaut came to a crashing halt.

Probably the most affecting and effective song on the album is ‘Intruder’. You said in 1980 that you wanted to "create a sense of urgency" in the listener, now given that this version is even more creepy than the original, you must be pleased with the results.

PG: I am yeah. I think it owes something to Bernard Herrmann and Hitchcock, which both John and I both discussed as an influence but yeah, it is nicely creepy.

How was it received at the time? Critics and audiences alike have never really had a problem with novelists and film makers using characters to tell a story but often do with popular music for some reason. I mean, ostensibly it’s about home invasion but there’s also some much darker stuff being hinted at as well.

PG: Yeah, there’s a transvestite element, a clothes fetish. There’s part of me in that but there’s also a rape metaphor. It’s definitely dark but real. I always used to enjoy performing it.

These issues were at the forefront of people’s minds back then with the popular recognition of the women’s movement, the perception of society becoming more violent and a subconscious reaction to both of these things in the burgeoning video nasty market. You only have to look at crime statistics now however to see that, in terms of burglary and assault at least, we live in much safer times but looking at papers like The Daily Mail you wouldn’t know this. They try and instill fear into our lives. Have things got worse than they were in the mass media, and with everything that’s happened at the NOTW, have we finally found out how much people are willing to take from the press?

PG: Sensationalism sells. We’ve just got ourselves into an absurd situation. Part of my dream is that there is an alternative world being built around technology that allows things to change without going through existing systems and governments. For example, On Line Petitioning has over ten million members. And just now we had a petition of over 157,000 delivered to Jeremy Hunt and David Cameron about the BSkyB take over. We’d basically gotten ourselves into an impasse where our existing systems could not deal with these issues. The heads of all the major political parties believed they could not get elected without the support of the Murdoch newspapers. The PCC is a toothless poodle, without any real powers that never does anything effective against press intrusion. The police relationship to these newspapers seems totally corrupt. Intrusiveness was taken for granted, regardless whether you think celebrities should be in the media or not. There were absolutely no moral qualms from anywhere. Information was to be gathered by whatever means. And this had to come to an end. To me journalism encompasses the highest attributes of human behaviour. There are people going out all over the world, even though they know their lives are at risk every day to investigate the truth on a daily basis and also the lowest forms of human behaviour such as we’ve seen here on the Murdoch papers.

They don’t give a shit about any suffering that other people are going through, as long as they get paid for that information, they will do it. But basically there needs to be a platform of privacy that can be protected by an independent ombudsman of some kind. They could, of course, work in the opposite direction and free up information when it was in the public interest. This phrase, as has been said before, does not mean what the public are interested in. These things are totally different. And if you let the press loose on that, there will be no morality and no privacy. The big picture is that in some ways privacy belongs to the last century and we’d better get used to it. But when there’s no right to justice or no right to the truth and no means of exposing injustice, or when injustice is uncovered but there is no one to publish the story, then we have real problems. And until we come up with some alternative political system, we have to rely on brave individuals – it was someone from the Guardian this time – or accidental exposure to protect us. And that’s not good enough.

Back when ‘Intruder’ came out, it wasn’t just the lyrics that had an impact. The drum sound on this track went on to define a lot of pop and rock music in the early 80s, with the revolutionary use of gated reverb. I was just wondering if you could talk me through this and what role Phil Collins, engineer Hugh Padgham and producer Steve Lilywhite played in this?

PG: You’d probably get three or four different answers to this question depending on whether you asked me, Hugh Padgham, Phil Collins or Steve Lilywhite. My version is that Hugh had already used gated reverb on an XTC album but he used it as a colouring agent in the way that people use FX. It is my belief that when the song was written around my basic [drum machine] programmed pattern, it originally had a much fuller arrangement. When Hugh put on the gated reverb, I got incredibly excited by it and I thought that it was going to change the way that drums sounded. I said, ‘Let’s turn it up, let’s really put the drums loud and proud at the front of the mix and everything else will be subservient. I asked Phil then to just repeat that pattern from start to finish without putting in any fills. I also asked him to take all the metal off the kit, there were no cymbals and no hi-hats. I don’t think anyone would dispute that. [Collins, kept on going to hit bits of kit that weren’t there so they eventually replaced the missing cymbals with more toms, Ed] Steve is a great producer. He has many talents now but back then his main talent was that he was good at recognizing moments and getting great performances out of people. Hugh wasn’t sure about it but he created that thing. [Making ‘Intruder’] to me was the defining moment. But then of course the record that made the sound much more famous than mine was Phil’s ‘In The Air Tonight’. He hadn’t met Hugh before that session and he then invited him to come and work on all of his records and that song went on to become a massive international hit, in the way that ‘Intruder’ was never going to be.

Is this all water under the bridge between you two now?

PG: Oh yeah, we get on fine nowadays. Back in the Genesis days he was a very good drummer and I was a lousy drummer but that’s how I started so I still thought like a drummer. We’d be in the dressing room after sound check working on song ideas at the piano. And I remember encouraging him and saying, ‘You could make it as a singer if you wanted…’ Ha ha ha! But he always had his jazz sessions, he played with people like John Martyn and Brian Eno, he had a very different reputation then. It wasn’t an overriding pop direction then.

People forget about Brand X.

PG: Yes, they do.

You must forgive this terrible link, but while ‘Intruder’ is a fictional song about criminality you’re a very urbane gent and I’d like to imagine that you’re not a criminal. But isn’t it true that once on tour you were arrested by the Swiss police under suspicion of assassinating a German industrialist?

PG: Yeah. The Baader Meinhof terrorist group. That’s who we were mistaken for. It’s a strange story. We’d been in Italy and we were driving across Switzerland to get to a gig in France and we were running a little bit late. I said, ‘We’d better call the French promoter and tell him that we’re going to miss sound check but we’re going to be on time for the gig, so not to worry.’ So we saw a phone booth when we were driving through St Gallen and we parked on a yellow line and we were there for about ten minutes while I was trying to get connected. It was a very different world prior to mobile phones. I’d had some throat problems so I had a black scarf tied around the lower part of my face. [Bassist] Tony Levin’s wife was dressed up in military fatigues, which was quite trendy at the time. And so three good citizens phoned the Swiss authorities because Hans Martin Schleyer [A former SS Officer who was then the President Of The German Employers Association, Ed] had been kidnapped and murdered a week or two before. They told the police, ‘We think there are terrorists about to raid St. Gallen bank.’ So eight vehicles arrived with police carrying machine guns – not pistols – and arrested us. The scariest thing about it was we could see they were shaking with fear as they were arresting us because of who they thought we were but we didn’t have a clue what the fuck was going on. They forced us to the ground and searched us but didn’t find anything. I could speak a smattering of German, some Italian and I could make myself understood in French but they wouldn’t respond to any of my questions. They’d obviously been told not not to communicate with us. We were hauled in, in separate vehicles in case we colluded. When they searched the tour manager they found a leather brief case full of cash – which was totally normal – but in the briefcase was also a drawing of how to drive through town to get to the back of the gig venue for loading in. But they were convinced that it was a route map to the bank. We were all taken to this jail, we were all really scared, the women were all crying. I tried to tell someone at the jail, ‘We are all musicians.’ And he said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous. What kind of musicians travel without instruments.’ And I said, ‘Our instruments travel in another truck.’ But they didn’t believe me. Now, at that time we were doing a barber shop quartet version of the song ‘Excuse Me’, so with slightly wobbly, nervous voices we all began singing it in the cell. This got a smile out of the police and they agreed to have a look through our stuff again, and in the briefcase they found things like contracts for gigs in Switzerland and they got on the phones. It was another two hours before they let us out. We eventually arrived at the gig venue at 11pm and the French audience had started rioting because we were so late. But we did it.

Was it a good gig?

PG: It was actually. We were just so relieved to be out. Sorry, that’s a long story.

No worries, it’s a great story. And, if you’re going to get mistaken for terrorists – it’s got to be the Red Army Faction – the best dressed terrorists ever.

PG: Ha ha ha, yeah, it’s because they were all middle class.

Why did you decide to include a five minute field recording taken at Solsbury Hill before the track with the same name?

PG: It was a last minute idea and Richard my engineer did it. The reason was that Solsbury Hill is a "light" song and the rest of the album is, I think, a body of work, and each track flows from one into the next and it tells a story. And we put a lot of work into making it this way. But we had a lot of requests for ‘Solsbury Hill’ from fans. I thought, I don’t really want to put it on but if I do, I want to separate it from the rest of the album as a kind of bonus track but how the hell am I going to create that space. Then I thought, well that song grew out of sitting on Solsbury Hill meditating, so what I’ll do is ask Dickie to go up ‘Solsbury Hill’ and grab some ambience and I’ll stick that between the track and the rest of the record.

Don’t Give Up has taken on another conceptual layer in being recorded for New Blood. It’s a song performed in a style [American folk or Spiritual] that we associate with the great depression of the 1930s being used to address the human effects of mass unemployment in the 1980s. Unfortunately now, it looks we’re headed back in that direction. When the song came out originally you were staunch labour but now you’re to the left of this party. Did you feel betrayed by Tony Blair’s terms in office?

PG: Well, after all those years of Thatcher, that was the only time I’ve put money into a political party [Labour] because I wanted to help get rid of the Tory government of that time. [sighs] But with them [New Labour] even though the attempts to reform the Health Service weren’t always successful, they were from the heart but I hated them for taking us into war, like many people who supported that government. I’m much more excited by this alternative political process that’s growing up around mobiles and the internet as something to put my trust in now.

With ‘Don’t Give Up’, did you originally ask Kate Bush to recreate her part or did you choose Ane Brun for the project?

PG: Well, I wanted to do it this way because I’d been singing it on tour with Ane and she’d been doing such a beautiful job. There’s an interesting story about this song. Because there was this reference point of American roots music in it when I first wrote it, it was suggested that Dolly Parton sing on it. But Dolly turned it down… and I’m glad she did because what Kate did on it is… brilliant. It’s an odd song, a number of people have written to me and said they didn’t commit suicide because they had that song on repeat or whatever, and obviously you don’t think about things like that when you’re writing them. But obviously a lot of the power of the song came from the way that Kate sings it. Dolly later asked me to sing it with her on her TV show but I couldn’t because I was on tour. Ane has moments when she really sounds like Dolly, so I thought it would be interesting. She also has a cooler Scandinavian aspect to her singing which I like a lot. So I thought, she’s been doing such a good job of it on the road, I’ll ask her.

New Blood will be released on October 10