The tenement building in the gentrified Hackney back alley may now be overrun by trustafarian models but, down in the funky basement, arcane machines are being harnessed by London duo Paranoid London to produce the year’s most abrasive statement.

Like the anonymous 12-inch singles Quinn Whalley and Gerardo Delgado have been unleashing below the radar for the last 12 years, PL puts a personalised spin on an old sound, breathing life into the malevolent pulsing of uncut 1986-style acid house, bolstered by stellar guests. Nasty, dirty and throbbing like an uncovered radioactive isotope buried for decades in a burnt-out building, PL came to inject some much-needed sleaze and filthy invention into increasingly-sanitised modern music and have found themselves with the biggest bomb to hit UK electronica for some time.

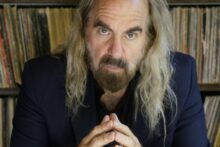

The day tQ visits the pair at their refreshingly-untidy HQ, it’s in the company of Secret Knowledge singer Wonder – visiting from Cleveland, Ohio – and New York studio legend Jay Burnett, of Beastie Boys and Afrika Bambaataa’s Soul Sonic Force fame. Infernal, sexy magic is in the air as a massive jam ensues around PL’s arsenal of analogue machines, those models of Roland innovation that gave acid house and Detroit techno its tools in the mid-80s.

In between swigs of beer, Whalley and Delgado are a flurry of knitted-brow concentration hoping for mischievous accidents to produce the kind of scabrous flare-up that peppers their new album – strictly on vinyl, like the 12-inchers they’ve been shunting out since coming together in 2007 with a mission to reintroduce acid house’s anarchic original spirit into a time when that wasn’t happening.

PL is the duo’s first specifically-recorded album, guests including Mutado Pintado, the late Alan Vega, Arthur Baker, ACR’s Simon Topping, queer scene DJ-poet Josh Caffe and murdered Californian gay activist Bubbles Bubblesynski. Stark. Confrontational and mainly constructed from their armoury of well-used 101, 202, 303, 808 and 909s, it’s making colossal new waves with an old sound spawned at a time before many recent converts were even born, though welcome to anyone who remembers experiencing its metronomic rush the first around.

When those first records arrived from Chicago around the mid-80s, perpetrated by mysterious names like Adonis, Sleezy D and Phuture, they bottled a mutant strain of raw insanity and luminous sex grooves that sounded totally alien but had been coaxed out of basic machines nobody wanted.

Then the revolution came, in the UK at clubs like Shoom and the Hacienda that unwittingly invoked a similar hothouse atmosphere to pioneering DJ Ron Hardy at Chicago’s Music Box. The subsequent airlift of the acid house template into mainstream dance music saw many originators getting ripped off, yet the creative electronic underground continued to thrive in early 90s London. That’s the scene this pair came up in, although Whalley had been to seminal UK niteries like Kingston’s Boiler House and the Wag thanks to tuned-in friends of his parents.

"It was the classic trajectory," he says. "We were hip hop kids who got into electro because it was the most happening thing." Then, adds Delgado, "We became acid house kids who went to Land Of Oz and Rage, then spent years producing or working in record shops until we started doing stuff together."

Whalley recorded as Slack with Justin Drake, including ‘Painkiller’ for Weatherall’s Sabres Of Paradise (weirdly, around the same time Wonder and I were on the label as Secret Knowledge – we must have met in a past life). Delgado worked in record shops, including the fabled Fat Cat, recalling, "It was always insane on a Friday when the imports came in. I probably sold more records to the most famous DJs in the world, including Jeff Mills, Pete Tong, Carl Cox; all these people buying their records for the weekend. One time I was sitting there writing the records up, sitting there having a joint with David Holmes, Andy Weatherall and Paul Daley. I just remember thinking, ‘Fucking hell.’ Being a kid and hooked into that was an eye-opener."

By 2007, although there’d been acid house revivals, electronic dance music had changed entirely as laptops and downloads replaced analogue gear and vinyl. The pair got so stoked by this systematic air-brushing of acid house’s dirty, hairy bollocks they started their Paranoid London label to strip the music back down to its original skeletal basics. As Whalley puts it, "We already had a perverse way of doing things. Records had died and nobody would have started a vinyl-only record label."

The pair’s 12-inch, vinyl-only missives started under the tag One Last Riot with a nerve-scrunching 303 declaration of intent called ‘We Make Acid’, guest vocals from old school acid sleaze king K-Alexi, followed by Chicago legend Paris Brightledge intoning the Fall’s ‘Immortality’ the following year. (These illustrious guests came through their manager Mark Potts’ Windy City connections.) After a two year break, they returned as Paranoid London with ‘Eating Glue’, their scabrous acid draped in vocals by Warmduscher’s Mutado Pintado, and two more Brightledge records. 2015’s self-titled compilation LP corralled some of these 12s, followed by electro entering the fray on ‘We Come To Rock’.

"A lot of kids didn’t know about it until fairly recently," says Whalley. "It’s not like you’ve invented the wheel or something, it was all already there. It just took somebody to come along and remind everybody to keep things really simple. We had this thing of just releasing it on record and not doing downloads, so people had to make an effort. You had to give a fuck in order to find it.

"We were lucky because, when we started putting out tracks, people had started doing stuff all on their computers, trying to make stuff sound like they’d done it in really expensive studios, like a great producer. Our thing was always, this is a few minutes of someone’s life on a dancefloor, it just needs to be dead simple and effective; a drum beat, bassline, some crazy vocals and you’re good. It was good timing. Without knowing it, everybody had got bored of mixing things well with nice-sounding tracks. We came along and reminded everybody it doesn’t need to be that difficult."

"When we me and Quinn had chats about what records we were into, it wasn’t the big anthems," adds Delgado. "It was the tracks you didn’t know the names of that you lost yourself in and thought ‘Wow, what was that called?’ The in-between ones, not the big records everyone knew. We don’t have any desire to make big anthems. It’s the ones in between!"

"We were mentally in love with acid house," says Whalley. "The people that were doing it years ago weren’t trying to make raw, banging records; they just had limited equipment. Paranoid London is us trying to make records like other people but, because we’ve being doing it for so long, we’ve ended up with our own sound. When you finally gain confidence to do your own thing, it comes quite naturally. It’s easier to work when you make your own rules.

"We’ve got an 808 drum machine, original 303, 909, a 101 and 202. That’s what we know how to use. Sure, if we were 19 years old we’d be doing it on laptops, but with our equipment you just turn them on if you want them to play on that bit of the pattern. That sort of equipment lends itself to getting stuff done quickly. It suits us, because we don’t spend a lot of time on each track. If you spend too much time thinking about it, you start to lose momentum and it gets boring."

That’s not to say PL didn’t also get sucked into the initial allure of computers, selling off their gear before buying it back again. As Whalley explains. "When computers started getting fast enough to do everything in the late 90s/early 2000s, we made the classic mistake of selling off the equipment thinking, ‘We can do it all on computer now’, then spent years boring ourselves shitless and never finishing a record. So we had to buy it all back. They cost a bloody fortune."

The new album is a riveting acid strike, snarling, throbbing and glazed by circuits jerked into life to spit analogue daggers. Josh Caffe lends vocals to two tracks, turning on the old school Jamie Principle/Robert Owens ache on ‘Starting Fights’ and desperate love song ‘(Vi-Vi) Vicious Game’, enhanced by melancholy pads. "He’s one of the only people doing really sleazy vocals nowadays," says Whalley. "Everything that comes out of his mouth is dripping with sexuality. There hasn’t been anybody that’s got that level of not-giving-a-fuckness for ages. He fitted in nicely."

‘The Boombox Affair’ turned into a cause after Bubbles Bubblesynksi’s was murdered outside a San Francisco strip club on the eve of recording his vocals. "Bubbles was a DJ trans-activist who was the beating heart of the San Francisco scene," says Whalley. "The week we were going to send him music to record vocals over he got murdered. When we were on tour in America about six months later, his friends said he’d been really excited about doing it, so we recorded vocals off videos on his Facebook page where he’d broken into a construction yard and held a rave on his own, then made a track. It just had to be done." Any money made from the record will go to local Bubbles-approved charities for trans gender sex workers and LGBT rights. "We’ve had messages from people all over the world. We only met him once but it’s been a heart-warming thing to do."

Enhancing PL’s commendable opinion that today’s music is too well-scrubbed and parentally-acceptable (short back-and-sides and shorts belong on Blue Peter field trips), Pintado rasps Bukowski-like gutter-sleaze over ‘Nobody Watching’ and ‘Just My Size’. Whalley and Delgado met him when playing New York clubs he was promoting.

"He’s one of the most creative people I’ve ever met in my life," says Whalley. "Painter, writer, poet, vocalist, front man for Warmduscher, another great band. Everything he says makes you think of the sleazy side of New York night life and fits really well with our idea of what people should be listening to in dark, sweaty nightclubs. What got us into the clubs was the freaks and the weirdos, but it gradually seems to be pushed further and further out."

"Music seems to have got a bit generic, recently," affirms Delgado. "It’d be nice to bring back a bit of sleaze."

Most special track may possibly be ‘Angel Of Hell’, featuring the unmistakable howls and screams of Alan Vega over its bubbling 303 cauldron. This remarkable cameo came about when Suicide played what would be their final show at the Barbican in 2015 and producer Arthur Baker emailed PL asking if they’d like to remix a track he did with Vega some years before. "As a rule we don’t do remixes but we jumped at it," says Whalley. "It never came out properly so we got in touch with Arthur and said, ‘This would fit really nicely with the rest of the album, would you let us?’. Arthur said yes and that’s how we got Alan Vega on our album. It was a dream."

Simon Topping appears expounding over dark Master C&J strings on ‘Cult Hero (Do You Wanna Touch Me)’; long-time ACR fan Delgado’s personal triumph, achieved after they shared a festival bill with Hacienda DJ Jon Da Silva, who gave them Topping’s phone number. "Simon paid his own ticket, came down to London, recorded and that was it. He’s a legend and just fitted perfectly into what we do. If we can make young kids go back and find out who ACR are it’s a good thing. It’s good to use people like Vega or Simon so people discover their albums then go and make their own music."

Crucially, these guest slots are matched by PL’s own tracks, including pressure cooker 808-909 assaults ‘Drum Machine’, ‘The Music’ and squelching ‘Blue-Ish’. This is what they’re like live, currently taking it around the US. The pair relish taking their ancient machines on the road, despite predictable hiccups (and being paid not to play a "super-rich yacht club" in Ibiza).

"Our 808 and 303 are fucked and it’s always chaos but that’s what keeps it exciting," laughs Quinn. "We take them all over the world. They’ve taken a right battering, but they’re still going! Sometimes we’ll soundcheck everything, then ten minutes before the set the 808 won’t turn on and we’ll have to do it with the 909. Half the time it’s all going wrong, but one of our greatest joys in life is when we turn on our 808 and get that ‘Boom’ through a huge sound system."

That could be the whole PL ethos there. Special, seismic and so right for turbulent times desperately in need of rebel machine music.