Photos by Flavien Prioreau

Movement is a constant in the life of Parisian musician, dancer and digital artist NSDOS, real name Kirikoo Des. “Movement is me, it’s my first love,” he says at one point during our interview. We’re speaking in the context of an ongoing project with itinerant festival Phonetics, which is taking him from Algiers to Lisbon and back. In Algiers he has worked with Xavier Boissarie, the creator of augmented reality technology Orbe, on a loosely Stalker-inspired project: “I picked an architect, a writer and a dancer and asked each of them to name three places in Algiers: one where they feel safe and well, one where they feel unsafe, and one that would be an interesting artistic space, and they gave me the GPS coordinates. So I imagined an app which, based on these locations, would allow you to leave messages for people, in the form of music or a poem for example. So if you wanted to listen to the poem and you’re on the app, you have a map showing the places where you can go to hear it. It’s a bit like secret agents leaving hidden messages for each other.”

NSDOS’s work has taken him around the world, for various projects in the UK, Italy, Japan, Alaska and Indonesia (a projected collaboration with a gamelan school was delayed by the coronavirus pandemic.) But it’s not just about travel; movement, and the interactions between bodies and technology, have been a common thread since he started out as a hip hop dancer on the streets of Paris. For his superb Intuition releases he has captured data from natural movements in Alaska, and his Clubbing Sequence project had music respond to the motions of dancers in an “augmented” club environment. He’s also an inveterate hacker and has performed on stage with a customised tattoo gun, triggering sounds as he leaves fresh marks on his arms. “That wasn’t so much about the act of tattooing but about electronic musicians. At what point does he engage his body, especially when there are interfaces, keyboards and knobs? The body touches things but isn’t affected. I wanted to see at what point I’m affected by my own performance, and what remains of it. I still bear the physical signs of this performance.”

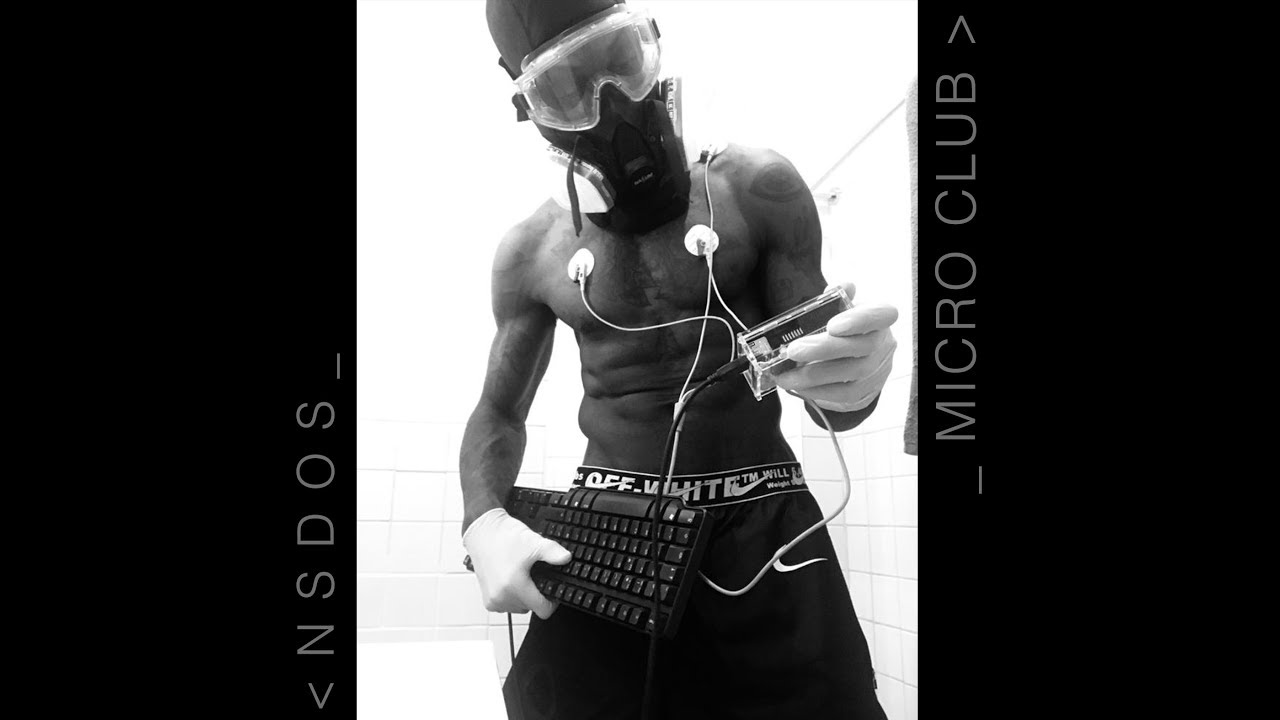

His most recent album Micro Club, meanwhile, was an exploration of the body within the sometimes extremely restrictive context of lockdown, with movement – and especially dancing – reduced to a bare minimum.

What were your impressions of Algiers?

Kirikoo Des: It reminded me a lot of Cuba, maybe because there is some of the same Haussmann-style architecture that you find there as well. It’s a place that shook me up, in a really positive way. You can feel that certain, really intense things have happened. But at the same time there is a prolific future that is possible. There’s a tension between the past, present and future that’s really stimulating. Sometimes it’s difficult to create a new story – you can see that with our cities, like Paris and London, the past is sublimated to a degree that it’s difficult to build something new. In Algiers there’s this thing where you can anticipate the movement, it can kick off or it can be calm. If it goes off, it’s chaotic. What was funny was that where we were working, which was a gallery on La Rue Didouche Mourad – a bit like the Champs Élysées of Algeria – it was just three days before the revolution [the 2019-2021 protests in Algeria] which started there! And at no point did any of the three protagonists of my project mention that things were going to kick off.

As well as working with the Phonetics festival, you’ve done residencies in places like Somerset House, and performed at the Villa Medici in Rome, the Wysing Polyphonic festival, and so on – do you feel most comfortable in these hybrid, interdisciplinary events and spaces?

KD: I’m comfortable anywhere, but it means making choices. If I’m somewhere like Somerset House, it’s important that at no point I say to myself that I have to remove the dance music side of what I do. And if it’s a show or club situation, I’m going to bring my motion sensors. I created my own and I’ve been using them for several years. I worked on a project with divers for example, and I captured a lot of aquatic sounds, and I think it’s interesting to be able to take that data and use it in a club context. The club experience is very formatted, with its build and drops, and ultimately just refers to itself. We’ve understood it, you know? So what else can we say? Can a drop be a field recording, something we’ve recorded in the country? It’s not easy and I’m quite stubborn on this point, to the point where I get festival programmers who can’t really envisage it and aren’t interested, but it’s not going to stop me from trying.

Your album Micro Club was a response to not being able to access club spaces at all.

KiDes: I responded to Covid like anyone, asking myself what I could do, how I could work, how to address my audience. And for me the question was ‘what makes a club work?’ It’s the body moving in a club. If there’s no-one dancing, there’s no clubbing. Obviously behind it all there’s an economy, but it all starts with people dancing. If you’re isolated and you want to dance, you still can but where and how many of you are there? Where I was there were two of us, so the ‘micro club’ wasn’t more than two people. And in the end it was just me, in the bathroom. I put all my gear in there because the bathroom had a club-like atmosphere, with the mirror and the lights. So I didn’t stop celebrating the club even though there wasn’t one. It was about how you keep memories alive too, how do we hold on to something so that when Covid is over we could be completely ready.

You’re not anti-club at all, you just want to see more exploration and interaction

KD: Absolutely, I grew up with club culture. When I was a hip hop dancer, I started in the street but then when it became impossible, so it was the clubs again which were the places we went to. So a club for me is connected to how people communicate with each other. There are many ways to make it so that, rather than looking at the DJ, people look at what’s happening around them.

When did that shift from the street to the club happen?

KD: It was thanks to [former French president Nicolas] Sarkozy, there was all the tension around terrorism and so no more gatherings of more than ten people, something like that [as a result of the Loi Pour La Securité Interieure, passed in 2003]. When I started hip hop dancing, we were dancing in shopping centres. At the Trocadero, near the Eiffel Tower, and there was a place under the arch of La Défense [a major business district to the west of central Paris], called La Coupole, and you could find more than 300 dancers practicing underneath it. I remember, when you said hello you had to say it to 300 people, it was like a ritual. And then the law changed things, so after that it was the clubs – Les Bains-Douches, another place near Montparnasse also called La Coupole, Le Queen and Le Djoon.

Those places were really important for hip hop culture. Le Queen was the gay club on the Champs-Elysées, and it was very ahead of its time when it came to house dance. The first house dance group in France, called Queen Step, started out there.

All the house culture from Chicago, Detroit, all that arrived in France thanks to queer culture. It was something I’d never seen before – you had the regulars who came dressed for the club, and then we arrived with our backpacks, towels, bottles of water, in our baggy tracksuits, and we had another space, another dancefloor, where we could do our thing. And then Le Djoon was very house-y, with a bit of broken beat and that kind of thing. And that was cool because I started DJ-ing too.

So from there you started making your own music?

KD: Yes – to begin with I was dancing, DJing, I play drums in a punk group which led me more towards a DIY, noise thing. And as my father was a sound engineer, I always had the idea of computer music in my head. Then I went to two dance schools and from there I began to become interested in generating music using my own movements. So it came little by little, with me teaching myself how to use new technology.

Have you kept touch with the rap scene in France? I realised quite recently that you produced a track by rapper Riski, ‘China Club’, that I really love, with its waiter’s eye perspective on a Parisian cocktail bar.

KD: My sound engineer is very close to all that, in fact I have people around me who work on mainstream rap projects – SCH, PNL, or with people like Lala &ce. I know Riski because of a kind of movement called ‘la ride’, which is a state of mind where you go from party to party, staying out in the street. We haven’t forgotten where we came from. I started out in hip hop by ‘riding’, going from suburb to suburb to see people and take part in battles.

And one day [Riski] came to see me about doing a track but not a hip hop thing, just with me doing what I do live. And it was perfect. But you see there’s this thing where we’ve got a bit of hang-up about electronic music, contrary to the US, where you’ve got people in Detroit making electronic music which is still street. In France it’s reserved for a certain section of the population, whereas there are people making electronic music who don’t really see themselves fitting into the kinds of places where that music is played. So there are very few connections between rappers and electronic producers.

I feel as though there is a greater awareness now from beatmakers in the French rap scene that they are making electronic music, and that manifests in the way they’re incorporating 2-Step, Jersey club and other styles.

KD: Yes that is changing but it’s still disconnected from the club scene, so you won’t see them playing at a techno event whereas really it should be possible. These connections are less obvious than in the UK, there isn’t the same curiosity or the courage to try new things. We digest things differently. But hybridisation is something that motivates me, and I have an opportunity now to work with a young rapper. It will have this NSDOS influence but can take off into jungle, or a broken beat thing.

There are traces of jungle in your most recent track, ‘Mount Lico Dream’.

For me there are major types of music that influenced me as a dancer, which are really 2-Step, garage, broken beat, jungle, things that always fascinated me in terms of the effect they have on my body. While I was in lockdown I listened back to a lot of classics and explored some new things too. Things like Ramadan Man/Pearson Sound, who is one of my favourite producers. I wanted something in my music that is like an homage to that, without me necessarily making jungle, but finding a way to reappropriate it for myself.

Does a new project start with new technology or a new process?

KD: Yes, that’s often the case, a new project usually comes from me having discovered a new way of doing things, although there’s always something conceptual behind it. Like ‘Mount Lico Dream’, I had a new modular synth, new machines that made me want to try something – it’s like when you go back to school and you’ve got your new schoolbag and a new pen, I’m going do some good work this year! So yes, it’s always stimulated by technology, the new.

NSDOS performs as part of Phonetics Festival, the next edition of which takes place in Lisbon from September 8 to 11. For tickets, the full line-up and more information, click here