What do you do when the most exhilarating moment of your musical life has already risen and fallen by the time that you are just fourteen? For Jack Bowes, the electronic producer who operates under the name of Rainy Miller, this was the explosion of mid-00s grime in the Lancashire city of Preston. “Fifteen years down the line,” he says, eyes looking away and still visibly awed at the memory, “I’m still like, that’s the sickest thing that’s ever happened in my entire life.” It was, he says, insane. “It gripped the whole city. Preston isn’t a big place, but it had real life micro-celebrities in terms of these MCs.”

Names like the Clean Cut Connection as well as Worthy, Killer or Agony may have escaped the annals of grime history, but became Gods of the South Ribble, blazing a trail from Chorley to Grimsargh. “There’s YouTube videos of clashes in Brookfield taken on LG Chocolate phones,” he enthuses, “I’ve never seen anything like it since, it was proper thrilling.” But it all came crashing down. “The whole thing collapsed. In Year 9, it just got really uncool to be MCing. Everyone thought it was lame.”

So what do you do when the most exhilarating moment of your musical life has already risen and fallen by the time that you are just fourteen? Jack Bowes was going to be a PE teacher. “I love football innit,” he grins, “so I was like, fuck it, I’ll just get back on the football.” It didn’t last: the PE departments of Lancashire’s loss would be British music’s gain.

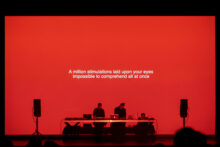

Forty-eight hours ago, Jack Bowes was in Paris, debuting the live show for his upcoming Joseph, What Have You Done? album at La Station club. On getting back to England, he has today been working a video shoot in Stockport with Preston contemporary, Fixed Abode label signing and frequent collaborator Blackhaine, bombing it over from the shoot in an Uber to our interview in the Lancashire borderlands, in a club on the second floor of an Oldham mill.

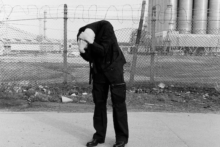

Though music writers have tended to dust off their glossaries of urban gloom when discussing Bowes’ output, in person he is affable and upbeat, a model of politeness and rarely more than an 808 beat away from a bright, beaming grin. Dressed in a black jacket that remains zipped up and sporting a closely cropped head of tight black curls, Bowes, 30, tells me that he is never normally worried about putting personal information out through art (“that’s almost the life’s work”) but today is unusually wary of discussing an album so centred on a time “when it all just went tits up.”

Joseph, What Have You Done? has been half a decade in the making. Whilst working on 2022’s melancholy Desquamation (Fire, Burn. Nobody) album (released on The White Hotel’s HEAD II imprint) and A Grisaille Wedding 2023’s more impressionistic Space Afrika collaboration, Bowes was stockpiling work that suited a more closely personal mood.

Whilst continuing the Rainy Miller sound world of drizzly ambient and a noticeably celestial bent that has been in his work since that 2022 release, Joseph is the producer’s most satisfying artistic statement since his 2019 debut Limbs and quite probably best record to date.

Spliced with iPhone voice notes that tell a highly personal story (more on which later) in fragments, the aggro Lancs drill that introduces the record is a red herring for a sensitive and tightly composed beginning-to-end journey. Take the spidery, mournful ‘Mary Magdalene, As A Home’ (at five years, the oldest track on the record) or the extraordinary lead single ‘The Fable/The Release’, whose haunted falsetto and rising percussion over smoky, burnt treacle textures unexpectedly recall late-era Radiohead, both making use of Bowes’ new favourite toy: the guitar. A novelty for the teenage hip hop head, he borrowed the instrument from a mate and – rather than, say, learning chords – simply listened to music whose emotional palette matched the emotions he wanted to convey, detuning the strings to align with them.

This is emblematic of Bowes’ creative approach. “It’s only ever guided by: emotionally, what needs to be said here?”, he explains. “Then I go away and figure it out. I’m not a noise musician, for example, but I know what noise music conveys and can do to me, so that’s present when I need that anger.” Coupled with this spring’s excellent new Aya album, the new album reflects a North West underground that may be splintering away from its onetime Greater Manchester base but has never been healthier.

The album’s real eureka moment began with divine intervention.

“Christ sent me a documentary,” he begins. This is not the well-known Nazarene, but The White Hotel’s in-house poet Christ “Christ The Poet” Bryan. Watching the 2003 BBC travelogue Searching For The Wrong Eyed Jesus (happily freely available on BBC iPlayer), Bowes was captivated by musician Jim White’s journey into country music and Christianity in America’s Deep South. “Obviously it’s never been my experience being in the Southern belt, but the way that they talk to each other,” Bowes explains, “the folk tales and the folklore” reminded him of Lancashire upbringing. He’s begun to pioneer a term for it: Northern Gothic.

“It’s that thing of the UK being the subtle cousin of America,” he ponders. “We don’t have the grandiose rivers of the Mississippi, but we’ve got Dinckley in there,” a lovely reference to the tranquil Lancashire brook where a suspension bridge connects Langho (where this author was born and raised) to the more affluent and historic village of Hurst Green. (JRR Tolkein taught at Stonyhurst College, the Jesuit private school in Hurst Green, the rural idyll of Shire Lane feeding back into The Lord Of The Rings.)

This introduces one of Bowes’ central missions. “It sounds ridiculously narcissistic,” says Bowes. Go on. “But I’m going to be the only person to tell the story about Longridge people.” This is fair: Longridge, population about 7,500, is a small, rural Ribble Valley town just north-east of Preston. Far more This Country than People Just Do Nothing. With no functioning train station for nearly a century, the town is tight-knit, but this is no escape story. Bowes loves it. “It’s full of people who are your aunties, but aren’t actually your aunties,” he explains of the town he returns to weekly. The town has a few shops, some normal pubs and, until its 2021 closure, the Edwardian-era The Palace Cinema, an unusually patriotic picture house that blasted the national anthem before every screening. “There’s nobody making art in Longridge or about Longridge. You have to romanticise where you’re from. You’ve got to proper lean into the romanticisation. That is everything.”

Peaking in 2006, Preston was the site of a still largely inexplicable, and scratchily documented, grime wave. This did not really happen in other neighbouring Lancashire hotspots, where donk and bassline still ruled. Watch the video for Clean Cut Connection’s incredible Livin’ in Preston City (some of this swag came from Preston’s then newly acquired city status) and the topography of Lancashire is confidently displayed in a way that’s both a hilarious North West reality check and a powerful affirmation of Preston identity. About two minutes in there’s a flash of Preston Bus station: here was a new modernist form thriving in the North West city that, more than any other, is defined by its architectural modernism. Not just Preston architects Keith Ingham and Charles Wilson’s enormous, rhythmic bus station but the 1970s Guild Hall (currently closed due to RAAC being detected in the roof) and Roger Booth’s absurd sci-fi classroom at Kennington Road Primary School. Another video just about sums the movement up: widely clipped on TikTok, a kid freestyles in front of a house and is interrupted by an old man coming out of the door and – walking stick akimbo – telling him to fuck off in a rich Lancashire brogue.

Like seemingly every kid with a PR postcode at the time, Bowes began writing bars. “Being ten or eleven and recording a song,” he reflects, “even just being around microphones, the most rudimentary thing in the world, you have that for life then.”

He remembers a summer day in the genteel country village of Grimsargh, being summoned to visit the MC Agony on account of his “mad, skippy flow” and locally infamous “stutter” trick. I ask the underground producer if he can recite any of these primitive, juvenile bars. Gamely, he dives right in. “Sharp digs from the left and right,” he begins, “mess with my fists,” – a little stutter, like a skipped CD – “and they don’t bite.” He laughs. “It was this beatnik throw-off, and everyone was like woah, this kid needs to go and see Agony!”. But his encounter with the Godfather of Grimsargh grime was a false dawn: within months, the whole thing was over. “We knew nothing like that was going to come along again.”

Others fell away, but Bowes kept on making beats, rapping and expanding his hip hop syllabus. “Things like Reasonable Doubt, Jay-Z and Biggie, they’re globally well known,” he says, “but in Longridge? That’s weird innit. Like oh there’s weird shit going on over there.”

By the time that he was 21, working in a computer storage warehouse in Ribchester (the ancient Roman village where, remarkably, The Sex Pistols played The Lodestar pub in 1976 after the council killed their Preston show) when he decided to commit to music with all his heart, no excuses, and enrolled on a music production course at Salford’s Futureworks music higher education centre. “My friends took all my stuff over with me and dropped me off. I was the only one who clung onto the pipe dream in that sense. It was with me to be like: you’re going to be the one out of the group of friends that does something.”

“When all that kicked off,” he says, “I didn’t want to sleep on that sofa in Ancoats anymore.” Because it wasn’t conducive to creativity? He shakes his head. “Because it’s rude innit!” That’s me told. Besides, the new Manchester economic model was making life for musicians increasingly unaffordable (“rent was just creeping up then, it’s crazy now”) and he sensed that his work was growing in an increasingly Lancastrian direction. “I’d gone to Manchester and the only thing I ever wrote about was home,” he tells me of the city that he presumed would be the making of him. “I never wrote about anything to do with being in Manchester, so maybe I don’t actually need to be there innit?”

It was whilst plotting his Lancashire return that events central to Joseph came to a head.

“I’ve lived a lot of my life feeling very scorned, or disadvantaged,” he says carefully. “Because of this one experience with past trauma. The person who should have been my father, and what that meant for other people in my life.” By the time that Jack Bowes was born in 1994, his biological father was barely on the scene, which hardened to no contact.

At the start of 2020, Bowes was coming back from viewing the house that he would go on to rent through the pandemic in Preston. “The day I went to view that house for the first time,” he continues, “I saw my biological father for the first time in 25 years on the street.” Bowes’ memories are hazy – they were hazy almost as soon as it happened – but he was walking past St George’s Shopping Centre when he saw the man walking towards him.

“It was just in passing.” How did he know it was him? “You just know. I had a physical reaction to it. It blew my head off.” Bowes ran down the high street and into the large 19th century train station. “I was just crying in the train station,” he remembers. “It proper fucked me up.” He damps down his dark curly hair in motions with one hand as he recounts the story.

“Then, there’s almost a suicide attempt. That’s what the whole thing culminated in.” The days following the sighting were difficult, unearthing a lifetime of emotion, and one particular day began to take on a lonely and unusual air. It’s recounted on the album in the delirious, one minute track ‘An Obsidian Lake Spews Out Of Me’.

“It was a weird day,” he explains. “I was walking, thinking, yeah. I’m going to go. I’m good to go.” Bowes did what anyone should do in that situation: he took a beat, and phoned somebody close to him. “I spoke to my Mum. I was really fucked up and she was like, ‘I need you to ring the doctors.’ And I did.”

Things got better. “A week after that happened, I found a girl,” and the new relationship – though it ended last year – helped him to recover from what he describes as a breakdown. “That period, it saved my life but also just took so much away from it.”

Bowes says that the album is “a tangle of all my experiences with male influences and fatherhood.” In particular, it is a salute to the man who raised him. “I have a stepfather,” he says. “No, it feels disrespectful to call him a stepfather. He’s a Dad.” The grin returns. “I call him my old man. The whole record is named after Joseph as a direct reference to Joseph of Nazareth, who raised a child that wasn’t his.” It’s this album’s contention that Joseph, husband of Mary, is both a hero and undersung masculine role model in his unfussy commitment to cracking on with raising another man’s child. “Even the framing of the album name, it sounds like he’s done something wrong. But he’s not! You have literally saved someone’s life. And that’s what it feels like.”

In fact, his name Rainy Miller was always, Bowes says, not an offbeat reference to the tricycle-riding owner of Colley’s Mill from Camberwick Green – part of the extended Trumpton universe – but an obscure tribute to the man who raised him. (Today, Bowes swears he had never heard of Windy Miller until the moment he told his grandma his stage name.)

“My old man,” he says proudly, “his surname is Miller. And Rainy came from me and my mum when she was a single parent. I was very little and we’d drive around in the rain and I’d sing about the rain. The root of all this music is a homage to that.”

The years that Bowes was making Joseph saw not just profound personal shifts, but the Rainy Miller project properly take-off. Him, Blackhaine – who went to Cardinal Newman College in Preston at the same time as Bowes – and Space Afrika became “a bit of a crew.” Bowes remembers them being booked to play Berlin’s Atonal Festival in 2021.

“I remember going to the emergency passport office in Liverpool because I hadn’t been away in so, so long,” he laughs. “You can’t not be excited about that innit. The experimental circuit was just super new to me.” (He will be bringing the Joseph show to Atonal next month.) Coming up during the Covid-19 pandemic, and his association with a ready-made experimental audience at The White Hotel meant that “we never had to do all that three people in a crowd stuff. We were always in front of a crowd, and the only thing I’ve ever known is pretty decent audiences.”

Being Rainy Miller is now a full-time job, paying the rent on the Leyland flat that he found on Facebook Marketplace (no respectable letting agent was willing to let to him as he had not been full-time self-employed for three years.) “You’re talking about such a finite amount of people who do somewhat experimental music and get to do it as a job.”

But still, in any other decade than our own, I tell him, artists like himself or Iceboy Violet might have had a more healthy relationship with the mainstream. “We talk about that a lot,” says Bowes. “I don’t know if it’s us being bitter, but I also think there’s a geographical thing sometimes. It doesn’t really matter though, does it? I always just felt that you’re on the path you’re on, and I’m pretty buzzing that it’s now my job.”

This introduces a thornier topic. Sometimes, for entirely noble reasons, Bowes has been asked to comment as a talking head on class in British music, and the enormous – and literally undeniable – reversal of post-war working class gains that allowed them to dominate UK pop culture between the 1960s and millennium. Following the 2025 Brit Awards, Bowes, like many, shared a meme on Instagram pointing out the elite educations of that night’s winners Charli XCX and A.G. Cook, with a caption about having “no seat at the top table.” But I sense that this comes reluctantly to Bowes. I ask whether it’s frustrating to be put in the position of having to answer questions about being a working-class voice in experimental music.

Calmly, but carefully, he answers. “I just think it’s so reductive to the message. I don’t know. I just think it’s such a fucking flavour of the month thing to talk about for so long now. The state that the country is in. Everyone wants this rebellion. And I’m like: fine. But they’re asking a rebellion from people, and we’re just musicians. Go and chat to bricklayers, or plumbers. I’m in touch with these people. My best friends do those jobs. It blows my head sometimes when I see these people every week and they don’t think about it at all. They just crack on.” He pauses, gently exasperated.

“Why is a sector like the arts and music so obsessed with this working-class thing, when nobody is involved in it? It’s weird to me. I think it’s disrespectful, actually. At the end of the day, you know, there are working-class people in music. But real working-class people are working. We can sit here and gather the spoils of being working-class, but we’re not, you know? People build houses that people actually live in. People live in their creations. You don’t want to sound like you’re licking the boot, because it’s not that at all. But the target audiences of people who read those types of things aren’t the people who need to hear it. It’s tired.” What he does feel more comfortable advocating for is Lancashire. You don’t have to be wearing one of meme-y North West zine Stat magazine’s Abolish Manchester or Lancashire 1974 t-shirts to recognise that, as Manchester becomes increasingly unaffordable, the city will become less of a lodestar to Lancashire musicians who traditionally moved to the region to make it. In fact, this can only be healthy for Lancashire creativity and identity.

The sun begins to hide behind the ever-growing Manchester skyline visible from the mill, as our interview comes to a close. Bowes is off for a drink or two at The White Hotel’s offshoot Peste bar, before heading home early: he’s got a five-a-side football in the morning. But on leaving, he’s keen to impress one thing about the project that has engulfed him for the last half decade, stressing that the album “is grounded in a lot more strength than it seems like.” A misconception about his work, he argues, is that “people always think it’s drenched in, like, something super depressing or sad.”

But it isn’t. “The whole record is a victory for me,” he tells me. “This inception of a mental breakdown, and then falling in love, and that saving me from certain things, and then falling out of love and how that feels.” A pause. “And then at the back end of the album is just pure adulation for the people who raised me.”

Joseph, What Have You Done? is released via Fixed Abode on 2 May