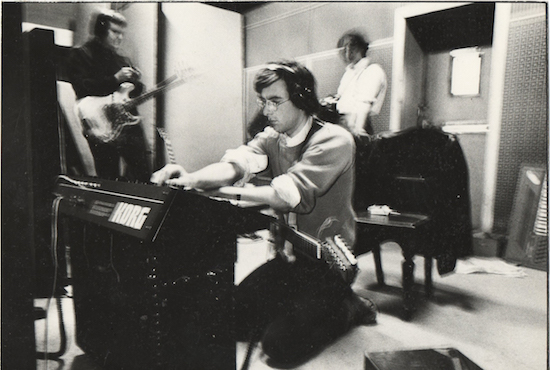

All photographs courtesy Normil Hawaiians

"I saw the Rolling Stones play in 76, and, oh my god, they were pathetic, " says Guy Smith, founding member of Normil Hawaiians. "Two weeks later, I saw The Sex Pistols. I just thought, ‘Oh wow, this is more like it!’ And it was the energy that was fantastic. The Sex Pistols got up, ‘One, two, three, four!’ Just going for it. That was needed. Diversifying a bit."

I’m talking with Smith and Simon Marchant, who joined in 1981 along with Mark Tyler and Noel Blanden after the group’s initial lineup split. It’s around freezing here in Michigan. My internet’s bad, and Skype is a tin can, but I’m transfixed. Tangential topics include: Hawkwind’s acid vibrations, Steve Severin, forgotten UFO sightings. (Guy: "I think that was Mark’s thing, the UFOs. There were some cosmic goings on out in deepest Wales late at night, when we would go wandering off having ingested some mushrooms. Some interesting things happening, that’s for sure.") But we’re meant to be talking about the creation of their should-be-classic debut LP More Wealth Than Money, originally released by Illuminated Records in 1982, and I must endeavour to stay on task.

"I really couldn’t believe how underrated as a group they were. I’m sure this has everything to do with Illuminated botching the distro at the time," says Christopher Tipton, whose Upset The Rhythm released their literally unheard Return Of The Ranters in 2015, and will reissue More Wealth. Tipton is probably right. When I finally hear the remastered record divorced from sketchy YouTube rips, it’s a revelation: all freely sprawling, improvisatory post punk, as representative of grazing fields as it is of Brixton. It feels like a complete expression of a space in time.

"Everything everyone does is influenced by a convergence of circumstance, people, place, politics, etc., but I think we’ve naturally focused our seemingly organised sound around these things to quite a significant extent," says Marchant. "It may be that, as none of us has a classic musician background, we’ve sought inspiration from other sources."

As an outsider, whenever I think about tQ’s notion of New Weird Britain, I often think of the totality of experience one might have while living on a particular island, in a particular place. Many of the artists in question manage, in often idiosyncratic or eccentric ways, to engage the weight of the landscape, of history – of history on the landscape – while bridging the urban and arboreal, the urbane and profane, the high tech and the pagan. In this sense, I’d argue that Normil Hawaiians – now a septet featuring Smith, Marchant, Tyler, Blanden, Alun "Wilf" Williams, Jimmy Miller, and Zinta Egle – offer a sort of philosophical blueprint for New Weird Britons to follow, and would, in an ideal world, already be considered one of the ur-bands for this movement of sorts.

I spoke with Smith and Marchant ahead of both the reissue of More Wealth Than Money on December 1 and the band’s performance with Richard Dawson at the Islington Assembly Hall. Read on for our discussion about improvisation, the album, its recording at Dave Anderson’s Foel Studios in rural Wales, and the future of Normil Hawaiians.

In 82, after Normil Hawaiians put out a handful of EPs and singles, you shifted your approach towards improvisation. I’m curious what inspired that shift?

Guy Smith: I remember I was doing sound for my mate’s band in London, and I looked around and I thought, "Oh god, everything’s got so stale. This really all feels the same." This is round about 1981, and everything was a little bit sort of Spandau Ballet, and everyone was wearing makeup with suits and slicked back hair…

Simon Marchant: Yeah! You included!

GS: Me included! The Hawaiians, forming in 79, we were always trying to push the boundaries a bit, but when the first crew split, I thought, "Now’s the chance to really try something different – go for what I really want to do regardless of genre." There were influences from the past. German bands: Can, Neu, Faust. In fact, one of the tracks on More Wealth is an homage to Neu – ‘New Standard’. It’s not nearly as good as Neu, but hey [laughs]. So, Simon – I met Simon at a gig.

SM: I’d been with a band of my mates called Greenfield Leisure, and in a way some of the influences were similar. We listened to a bit of Can, a bit of Eno, all that sort of stuff. But only half of the members of the band played conventional instruments, really. We used to meet up at someone’s house and spend the night just making noises. So, I suppose that worked really well with what Guy wanted. Guy wanted something different, and we had enjoyed doing something in a slightly different vein. It was in the rehearsal studios that Normil Hawaiians first started coming up with those long, improvised pieces that rather frustrated poor, old Cliff, our bass player at the time, until he had to leave the band.

GS: "Let’s improvise around two chords." Ten minutes later, me and Simon went, "Yeah, look at this!" And Cliff said, "Fuck that, I’m leaving." He just wanted to be Siouxsie & The Banshees. But Siouxsie & The Banshees already existed, so we didn’t want to go there. We didn’t have a bass player, in fact, when we turned up at Foel Studios.

SM: No, we didn’t, no.

GS: And of course, one of the great things about going to Foel was that Dave Anderson, who ran it, was the bass player of Hawkwind and Amon Düül II. For those who know Hawkwind, they’re almost godlike. So, we turned up, but we hadn’t met Dave before or talked to him. What a lovely place out in the hills in Wales. Really cut off from anywhere else. Of course, Dave turned out to be really personable. He played ‘You Shouldn’t Do That’ on X In Search Of Space by Hawkwind. It’s like, "Wow!" So, we tentatively asked him, "Would you fancy playing a bit of bass?" ‘Cause I played a bit of bass, Simon played some bass, Mark played bass – we all took it in turns, you know, depending. I think ‘British Warm’ was the first track we said, "Dave, can you play on this one?" And he’s really getting into it, and he’s getting almost a bit too rock-y, you know? And I think, "Well, we’ve asked Dave to play, we can’t tell him what not to do, really." But that’s what he was. It was terrific, brilliant. Nowadays, you don’t worry so much about that, but in 82, you did not want to sound like a rock & roll band, or at least we didn’t.

So, you were in Brixton – was the shift in landscape from London to Wales part of what made you want to record at Foel?

GS: Absolutely, absolutely. In Brixton and South London, there were some amazing things going on, but Thatcher and…

SM: It was a bleak time.

GS: Everything was being redeveloped with foreign money coming in. London felt like it was beginning to close down. We really wanted to get out in the country. That was brilliant. ‘Cause it was just us and Dave and Simon "Klaus Wunderkind" Pritchard who’d been in Greenfield Leisure. He had this total allergy syndrome. He had a cello with him, and he’d sit in a field just going [mimics screeching cello noises] on his cello. It was just amazing. He was just playing to these sheep. We were all coming from London, where it was all squashed. We just thought there was so much space. And so much time. We just worked until we finished – through the night, whatever. It was great.

You can really hear that space on the record. You can almost feel the landscape in the songs. It’s really interesting to me how the record, on songs like ‘British Warm’, will shift between a more expansive, atmospheric approach that seems really informed by the rural space you were in at the time and a denser post punk sound that seems more reflective of London and UK politics at the time.

GS: With ‘British Warm’, it begins with an African thumb drum, basically. The song’s about war and colonialism, really. The whole More Wealth Than Money concept in a way is saying, "Look what we’ve done to these continents."

And the Falklands War was on at the time. That was big in the UK, and it was a very specific war between the Argentines and British, racing towards each other for battle. It was quite dramatic, but also seemed so stupid. And you knew the people who were going were not the people who said, "Hey, let’s have a war."

So, ‘British Warm’ is partly envisioning Margaret Thatcher sipping tea with some African leader, while the West is just exploiting Africa, but it was also about war as much as anything.

Obviously everything over here in the States is a disaster, but More Wealth still seems applicable, because the Reagan and Thatcher years laid so much of the groundwork for everything that’s happening now. Their dismantling of the societal expectation of fundamental – I don’t know – decency is a terrible word, because I’m not sure if America was ever fundamentally decent…

GS: Or the UK for that matter, but it felt like it was. You know, in the UK in the late 50s, 60s, and 70s, it felt like things were going the right way. You had strikes and stuff, but you felt things were getting sorted out. When I left school at sixteen, I walked straight into a job. It was really easy. I became a bank clerk. Turned me into a complete anarchist, of course. "Lady Fowlington-Smythe is coming in. She’s got lots of money. Be nice to her!" And I’m like, "What?" Because then they treated someone off the building site like absolute shit. No one is better than anyone else. Better at some things? Maybe. But as a person? No one is above anyone else. I stayed at it for four years, but just took the piss completely in the end. Then Thatcher got in in 79, and suddenly, whoa. What’s happened? This whole yuppie thing was growing up in the early 80s, and it was horrible. All this greed. "Money, money, money." That really came up. The yuppies. The suits. So, we headed to the hills. For sanity. Brixton and South London were still great fun, but you were aware the world was changing…

SM: Changing every day.

So, when you set about making More Wealth did you know, when you went out to Foel, what you were shooting for? Or was the process more of an exploratory kind of thing?

SM: I think it was very organic. We had one or two ideas. How many tracks did we go there with? Maybe about four or five, I think? All germs.

So was Anderson simpatico with you guys, amicable to the way you wanted to work?

GS: Not totally. Not entirely, because he was a bit of a rocker. But at the same time, he had been in Amon Düül II, who themselves were pushing boundaries. And Hawkwind, in their own way, were off on these ten-minute tracks, sometimes improvising. So, he had an element of that in his makeup, anyway. So, that was really good. We weren’t harking back to pre-punk days, but there were some influences from the early 70s that got a bit blown away in the punk thing that we wanted to revisit.

SM: He was definitely cool with that thing about, just turn the tapes on and start playing. That was really helpful. That was one of the key things. Turn the tapes on and turn the lights off, I think.

GS: We used to rehearse like that. We would just turn the lights off and just swap instruments, do whatever you felt, no rules, anything.

When you started that shift toward more improvisation, did that affect the way that you approached your instruments and the equipment that you were working with, as well?

GS: From my perspective, I was never a great guitar player.

SM: Me neither.

GS: All around us there were great guitarists. I never particularly wanted to be like that. Not that I could, but I never wanted to compete in that. I had no interest in trying to become a demon guitarist. So, even in the punk days, when you listen to ‘The Beat Goes On’, we were trying to break away, trying to make noise, rather than just tunes, if you like. And Simon, of course, had a screwdriver that he would play his guitar with.

SM: Well, it was anything you could stick in it that would make it sound a little bit different, and maybe hide the fact that I wasn’t particularly good on guitar, either.

GS: Simon, you’re a good guitarist, man.

SM: Well, -ish, yeah. But I’ve never been interested in things like guitar solos, and that sort of stuff. I’m more interested in sounds, in what you can get from it. I think that’s always been our approach, really.

What are your plans for the future?

GS: We spent ten days in Kintyre, Scotland, and we recorded some really interesting new stuff. My favourite track is pretty much just the sound of the wind outside. It sounds amazing.

SM: Kintyre is on the west coast overlooking the Scottish islands, so it’s very exposed. We made this four-track recording of the wind, and we decided to filter out everything other than some tiny, thin frequencies, so that we were left with a sort of chord, and every now and then you get these blasts of wind, and that interacts with the delay effect that we had there. It’s very much a recording of the place and the time that we were there.

So we can expect to hear new stuff relatively soon?

GS: Absolutely, absolutely. We’ve also got Zinta, Simon’s wife, involved, because in the thirty years when Hawaiians weren’t playing, I did a lot of singing, often singing harmonies with women. I asked Zinta if she would sing with us. And that’s worked out well. She’s brought a couple of songs to the table.

SM: She’s developed ideas. In one new track, Mark had chords, and then Zinta and you made those amazing vocal parts, and she did the same for the one that I call ‘Twigs’. I just came in with a really intense series of chords, and then –

GS: It’s a bit intense, we might have to filter that out a little bit, Simon, that one.

SM: What?

GS: That track is very, very intense.

SM: You wait until it’s finished. You will love it.

More Wealth Than Money is out on Friday via Upset The Rhythm