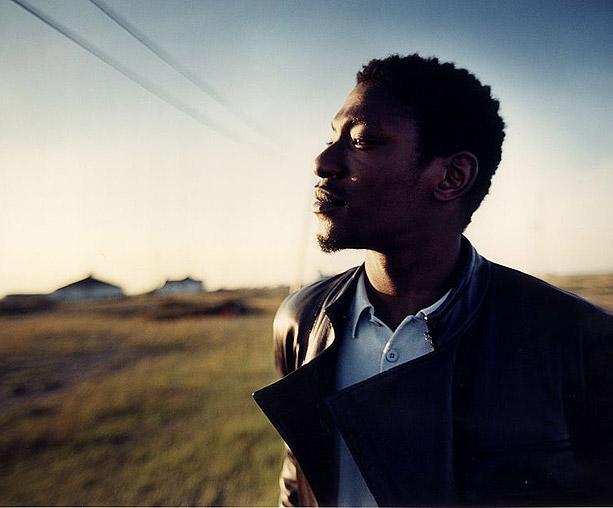

Rodney Smith is a diffident man, considering his métier of choice. Though notoriously, nothing is handed to British rappers on a plate, he betrays no sign of the self-assurance or venality we’re supposed to accept as preconditions for success. In the case of some of his former peers, it wouldn’t be overly pessimistic to chalk up another victim to public indifference. But here Roots Manuva is, four albums into what you’d call a career. Then there are three collections of remixes and dub versions – the latest of which, Duppy Writer, reworks material taken from as far back as his full-length debut, 1999’s Brand New Second Hand, as if to underline his longevity.

At the same time as it continues a theme, Duppy Writer is a departure. While the mongrel consistency of his records is normally hard to triangulate, here selected vocal tracks are matched to a painstakingly cohesive set of dub and digital dancehall backings. And whereas previous records have seen Smith’s own production augmented by a rotating assembly of talent, here he has handed over the keys to a single individual, producer Wrong Tom.

"Wrong Tom did remixes for Slime and Reason," he explains, referring to his most recent album proper, "and his take on it was emotionally quite in tune. It freaked me out to some extent. He put beats behind the a cappellas that made it seem as if I was referencing those beats. When it came to getting someone to do an extensive remix project, he was the first choice, because he really seems to be sensitive to the lyrical and tonal nuances that occur in my songs. I just left him to it and he used the a cappellas to his own taste."

Over the phone, Smith’s deep, discursive train of speech threatens to lose itself amid the sounds of a high street somewhere. He zoned out for too long in a shop, he says, and is only just now walking back to his car. While he’s enthusiastic enough in praising Wrong Tom, for instance, it’s difficult to tease out any frank reflection on the extent of his own achievements. He deflects enquiries in order to pay tribute to figures who passed onto him their tradition, as he puts it, "in a different way." This includes veteran dancehall vocalists Ricky Ranking (lately a member of his Banana Klan collective) and Tippa Irie, as well as the unnamed soundsystem operators who fascinated Smith as youth in South London. He modestly suggests that subsequently he "rode the crest of what they’ve done."

Of course Smith can’t really have come so far purely on the coattails of his mentors. His work has been fairly consistently been accepted by the rock press, by the broadsheets and by fans who have likely never heard of Tippa Irie, to their loss. Granted, sales of his first album proved slow-burning, but reportedly he doubled the figures with his follow-up Run Come Save Me. (He also picked up a Mercury prize nomination, for what it’s worth: not necessarily much given particular examples to the contrary.) In comparison with the average MC, then, you might assume his methods and approach somehow mesh more straightforwardly with the creaky machinery of the music industry.

Predictably he demurs: "Things just happen inside out and upside down. I’ve always got a stream of couplets and bars in my head that I’ll try out to anything. I’m constantly working, but Lord knows when my next album will be. I’ve got other things taking up time: doing nights, rehearsing, as there are going to be lots more Roots Manuva shows. Then we’ve got the Banana Klan soundsystem. I’ve just bought some speakers; it’s always been my dream, so it’s kind of coming full circle. Lord knows what’s going to come out of it all."

Almost invariably, Roots Manuva’s appeal has been partly accounted for, even if only implicitly, by reference to his Englishness. Put some of the blame, if you like, on the imagery of pints of bitter and cheese on toast in his biggest hit, ‘Witness (1 Hope)’. Really, though, this is a manifestation of UK hip-hop’s anxieties about identity (mainly in relation to US rap) by proxy. It seems a very quaint talking point, now that grime artists and their assault on pop culture have made it so easy to take Britishness – and more specific local identity – as a given.

Naturally Smith is aware of changes in the landscape: "It’s more likely now," he says, "that MCs and bass-oriented artists can be universally acceptable. In the past, if you wanted to make a hip-hop record, you used to be told it wouldn’t sell." And he will readily acknowledge that his antithetical relationship to purism is a very English thing. His feelings with respect to his own self-image, however, are generally somewhat curious.

"Because I travel so much, it’s definitely not a city thing for me, it’s a planet-wide thing. I had a beat recently from Dizz1 and he’s from Sydney. I think travelling has helped create a bubble for me and the Banana Klan. And we’ve got technology, so everyone’s got their laptops and most nights in the hotel there’s something kicking off.

"With the technology that’s available, the whole concept of the ghetto and the ends is probably going to change. I think it’s a time to try to connect with people beyond the end of your street. When I was making my first album I never thought beyond Brixton. Where you’re from might be significant when you’re thirteen, but as you grow up and travel you see a wider existence, relevant to the social and economic development of this new, undefined travelling class that there is now."

A new, undefined travelling class? It seems an odd thought in this context, but maybe for Roots Manuva it makes a certain sense. At one point he reflects on the way music invokes different lyrical "spirits" in him: "I suppose there’s the new-wave rasta Manuva, then there’s the eternal wondering church boy Manuva, and then just the linguistically exuberant Manuva. Sometimes it all happens at the same time." (He’s referring in the second case to the religious upbringing he received from his mother and his lay preacher father.)

The impression begins to emerge that this multiplicity isn’t restricted to his lyrics. It could be a long game of cat and mouse with himself, indeed, that has enabled him to retain the fascination of his audience. Even the comparative extroversion of Run Come Save Me unfolds by counterpoint with conflicted moments such as ‘Sinny Sin Sins’, which broods on his church upbringing. It’s probably not coincidence that Slime and Reason found Smith as creative as he’s been, and that despite the journey he’s made, at bottom he still doesn’t quite appear to know who he is. It’s unlikely that the one new song on Duppy Writer, ‘Jah Warriors’, provides any certain indication of his next direction, but it’s a fair bet that Roots Manuva will remain as productively unsettled as ever.