What a difference a decade or so makes. I first spoke to Trent Reznor in 2005 before the release of the relatively upbeat album With Teeth. It was a short, snappy, song based reaction against the perceived difficulty and unwieldy length of 1999’s The Fragile. The album was rumoured to be inspired by the musician’s experiences with cleaning up after years of untreated alcoholism and substance abuse, a tough process which was precipitated by an accidental heroin overdose. Worryingly, for me, I’d been tasked by a popular rock magazine with getting “the full story”. I was, at that point, unaware of the radical opening up effect a 12-step programme can have on some participants however and if I went into his hotel room that particular afternoon perturbed that I wasn’t going to get enough I left, an hour later, concerned that he had perhaps told me a touch too much.

The interview was great. Reznor was (and remains) an excellent person to quiz, in the sense that he treats interviews – like every aspect of his job – with a lot of thought and attention. But as much as he gave me what I wanted, the experience wasn’t exactly a barrel of laughs. There was a pervasive sense of world-weariness about him, a sense that he was expending a lot of energy just to complete run of the mill tasks, like talking to the press for example. If he was a cartoon character he would have had a small thunder cloud hovering over his head.

When I speak to him this summer, it’s in a similar expensive hotel suite, down a similar upmarket London street, under similar circumstances. (Nine Inch Nails’ ninth album Bad Witch, one of their strongest and shortest to date, is just about to hit the shelves.) These brief experiences you get with famous musicians from across the pond are so heavily mediated, so exceedingly well timetabled and organised, that you would suppose that the character of one interview would simply blend into another. But today the atmosphere in the room is so different that I’m initially paranoid that I’m speaking to some kind of imposter.

When someone kicks drink and drugs for good, by and large it’s a profound lifestyle change for them so they can’t be blamed for expecting to experience a profound change in their actual life. Of course cleaning up and drying out doesn’t actually change anything in the short term bar them being drunk, high, sick and hungover all the time. The real change that can happen is slow to reveal itself and hard won. This is where the completely unnatural experience of meeting someone in a professional capacity in a hotel room once every few years when they have an album to promote actually comes in handy. You get to experience the flip book animation version of genuine change; to witness the stop start film of the giant oil tanker changing direction at sea.

Or perhaps I’ve just caught him on a good day.

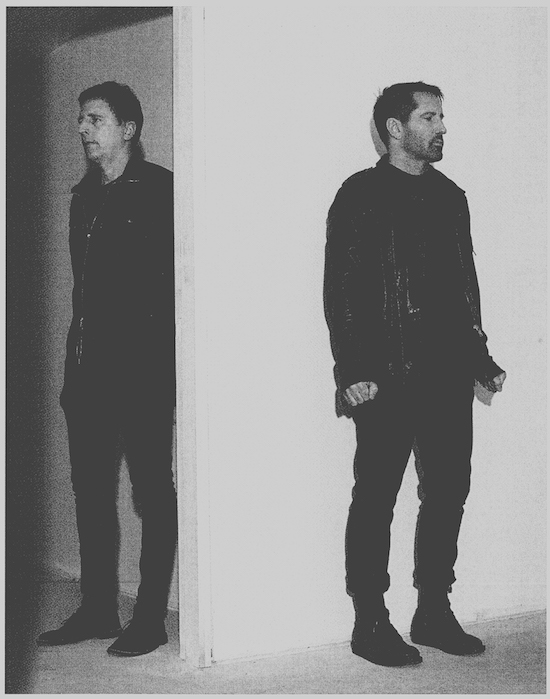

Either way the 2018 version of Reznor I’m getting to meet is much more relaxed. He looks very healthy and cracks more self-effacing jokes than you might expect. As coffee and mineral water is poured I ask if he’s going to be celebrating the band’s 30th birthday at any point this year. He claims he finds it “depressing to even think about” but he’s grinning as he says it.

I apologise to longstanding musical accomplice and currently the only other full member of Nine Inch Nails, Atticus Ross, who is also present. I wasn’t warned I was speaking to him until literally three minutes before entering the room so I’m not particularly well prepared for our encounter. He seems supremely relaxed and unconcerned about this information.

But why wouldn’t they both be relaxed. After a relatively quiet and reflective period for Nine Inch Nails, they have returned to the fray in a creatively revitalised manner. When they ended this hiatus in the closing days of 2016, Ross, a 50-year-old Londoner, who pinpoints acid house as his punk rock, was made a full time member of the band (a responsibility that Reznor had previously only bestowed upon himself). The pair released the EP number one Not The Actual Events, which was followed up relatively quickly by EP number two Add Violence the following July. And now this Summer’s 30-minute long Bad Witch LP completes the trilogy, each part better received than the last. “The momentum one can feel finishing five or six songs feels naturally different to that of finishing three times as many”, says Reznor, explaining the snappy pace of releases.

In the same period the band returned to the live arena after a break of several years as well with the pair framing it as initially something of a gamble. Reznor says: “We were put in the risky position of headlining festivals opposite artists such as Frank Ocean. He is our antithesis in a lot of ways, in that he’s hip and young. We didn’t go into these shows assuming that everyone had been chomping at the bit waiting to see Nine Inch Nails live. We chose the option of presenting the band in a very unpolished way. Our template was when we opened for the Jesus And Mary Chain in 1990 and it was just us, smoke, lights and chaos. We just wanted to go out and make the show feel like it was unsafe. And it worked.”

NIN’s upcoming extensive North American tour is spread out over the last four months of this year and will feature JAMC in support. Nothing, it seems, is left to chance and everything is done for a reason.

Another significant herald of the rejuvenation to come was spotted last year when the band appeared in the Roadhouse segment of ‘Gotta Light?’ – Part 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return – playing the track ‘She’s Gone Away’. While it’s hard to get any clear picture of who the full audience for the returning cult TV series actually was, it appears to have been a hit with millennial viewers and NIN (bar a returning Julie Cruise and an acoustic toting Eddie Vedder) were notably the only ‘vintage’ band to feature in the line up. Reznor is a lifelong fan of the work of David Lynch and originally wanted the director to make the ‘Head Like A Hole’ video, before the job went to Eric Zimmerman. A connection had been made however and Lynch enlisted Reznor to oversee the soundtrack to Lost Highway in 1997. Perhaps importantly, the NIN frontman revealed recently, the first track he submitted for Twin Peaks: The Return was rejected for not being “aggressive and ugly enough”, with Lynch demanding a track in its place that would “make his hair stand on end”. A willingness to throw material out and start again from scratch has become an important guiding principle over the last year or two it seems – as Bad Witch is not the album that they originally recorded, the first version – almost in its entirely – ending up scrapped.

The trouble with v.0.1 apparently was that while Reznor and Ross “thought deeply” about the first two parts of the trilogy before they even entered the studio, they had more of a “Yeah, we’ll get to that” attitude towards the final installment. Reznor says that their caution in returning to the live arena plus a growing awareness of mortality not to mention a more subtle age-related existential discomfort (“a sense that culture was becoming something semi-unrecognisable. Having to ask, ‘Is the world is getting dumber and weirder or is this just the sensation of getting older and us trying to determine what is real when viewed through this lens?’”) amounted to a dilution of their effort; it resulted in the production of predictable work.

Reznor laughs dryly: “We spent a couple of months in the studio and we realised we were treading water. It was something we were initially unwilling to admit because we were both experiencing some difficult… depression related events in our personal lives. Nothing musical; stuff outside of our control.”

This slump in energy and focus impacted heavily onto the process: “We’d come back into the studio the next day and ask, ‘Did it get good overnight? No, it still fucking sucks.’” They had recorded a thematically unnecessary, more-of-the-same sequel to the first two records. It took them two months to realise that they had taken a completely wrong turning somewhere: “Looking back I don’t know why it took us so long to come to that conclusion but when we did it was obvious. Just throw that shit out. Drag it into the garbage can onto the computer desktop.” Reznor seems quite honest in his auto-criticism but then that’s the difference between Nine Inch Nails and any of their still-operative peers from the field of American alternative rock. If you listen to the current output of Queens Of The Stone Age, Foo Fighters, Ministry, Jane’s Addiction, Pearl Jam, Smashing Pumpkins and Red Hot Chili Peppers, you’re forced to concede that either these groups stopped caring about what they do in the studio a long time ago or possibly never actually did in the first place. The tendency to throw out a generic album is understandable – why expel too much energy; it won’t sell as well as a canonical LP released in the 90s, in fact you’d be better off just repackaging and reissuing that instead. The attitude of ‘Let’s just crimp out a loss leader to kick off a large, income generating tour’, isn’t something that NIN have slumped into. In their insistence on seeing each aspect of what they do in terms of a creative puzzle that needs to be solved, they share more of a spiritual kinship with European artists such as Radiohead, PJ Harvey and Gary Numan. There is a feeling, no matter what you think about the music these artists make, that to them, this is undeniably stuff that still really matters.

A week before this interview I was sent the PR material ahead of the actual audio and while reading the bio, the phrase “self-referential” jumped out at me, as did the suggestion that they had given up on the quest to always be future facing. This gave me pause for thought – perhaps they too had finally slumped into releasing a generic no-frills “NIN album” to base a tour round. This is an idea that Reznor himself hints at without prompting: “We allowed ourselves to look inward and become self-referential at times. I realised that I’m allowed to pick up a guitar like I did back then and make it sound like that. It was fun. We had boxed ourselves into never allowing ourselves to think of nostalgia or the past. What we did always had to be fearless… And this time it felt exciting to hear a loud distorted guitar and feel aggressive… Who says we can’t do that? It felt right.”

And indeed anyone scanning the track listing and seeing the title of the opening track ‘Shit Mirror’ (my word!) might think that says it all. But does it? True enough if you asked someone to imagine what constitutes the NIN sound, the opening bars of this track is what would tickle the cochlea of their mind’s ear. But in illusionist terms, this is something of a misdirection. The song (and by extension the album) doesn’t dally too long in the realm of the machine-ground industrial metal. The rowdy Glitter beat, use of heavily distorted noise, percussion played with actual rocks and gleaming patent leather glam guitars make it resolve like T-Rex on PCP. The dynamic high contrast of styles and sounds being the last thing you would expect in the now highly codified realm of industrial metal. But then, for all of Reznor’s self-effacing game, that’s not what this album is and his suggestion that he has finally taken his foot off the pedal somewhat shouldn’t be taken at face value.

One of the real surprises and pleasures of the album comes in the smart use of saxophones. It would be way too much of a stretch to invoke the names of any of the great and good of spiritual jazz or Afrobeat here; instead let it just be said that the instrument is used to generate a sound which is raw and thrilling. And if you’re in a band that is in its middle years, no amount of trying to second guess what your fans want or studying the old blueprints can generate this kind of audio shiver. Much has been made in the press about the influence of Blackstar, Bowie’s farewell album, but I think the comparison to Donny McCaslin does neither party any favours and is, if we’re being honest, a bit tin-eared. (Reznor does use a croon which could be termed vaguely Bowie-esque on one track, but as with LCD Soundsystem’s much vaunted debt on American Dream, I feel like this comparison has been overplayed somewhat.) Instead I think of the playing as being a spiritual cousin to the elemental, sheet metal punching heavy blast of Steve Mackay of The Stooges. And this is all the more surprising given that it’s Reznor himself playing the horn.

He explains: “It’s surprisingly difficult to get outside the rules that you’ve learned over the course of your life. I had to smash these all down in order to allow Atticus to become fully 100% deranged. During this record I changed the way we worked. A lot of the time I switched to just providing ‘things’. Unusually for me, I would walk out of the room and when I came back into the room those things had become far more inspiring and significant than when I first walked out. We got some stuff out of a temporary storage facility and sat them in the corner of the studio thinking, ‘Let’s just have some things in here that could be inspiring.’ And two of those things were a tenor and a baritone sax that in the distant past I had been pretty proficient at.”

As a schoolboy Reznor played in his school’s marching band, concert band and jazz band and was “a fairly good improvisational player at the time”. He is the first to admit that he was never a fan of anything too avant garde: “If you’d asked me then I would have told you that free jazz sounded like five guys playing five different songs at the same time.” But the way the sax was played during the Bad Witch sessions became representative of a new way of working and how they “just made noise and tried things out, letting this experiment turn into something that had its own logic and structure and then not micromanaging it”. Reznor hasn’t been playing sax live in concert so far but refuses to rule it out, saying simply “We’ll see” when it comes to the Autumn/Winter tour.

Ross, who has been working with Reznor on NIN since With Teeth, pinpoints the decision to use sax as the “turning point” for the new album. He says after this the music sounded “exciting” and highlights how Reznor’s new attitude rubbed off on him as well: “Because I don’t really know about the saxophone it seemed like there was no real reason why I couldn’t put it through this particular guitar pedal or that particular effects processing unit. The first track we tackled like this was ‘God Break Down The Door’. It was in a particular key and BPM so Trent just played and played and played and then it came together really quickly.”

‘God Break Down The Door’ makes an exciting midway album peak when sequenced next to the other saxophone featuring track ‘Play The Godamned Part’. With the title hinting perhaps at the stresses musicians can sometimes face while in the white heat of the creative process (cf. Father Ted Crilly to Father Dougal Maguire while writing ‘My Lovely Horse’… “Play the ***** note”) I think it’s only fair to ask if the song title reflects the dynamic of their creative relationship.

Ross asks: “You mean, is it about us in the studio?” He laughs and says emphatically, “No.” Reznor sighs: “I was waiting for this to come up…”

Obviously with The Downward Spiral, The Fragile and Ghosts I – IV under their belt, NIN are no strangers to releasing lengthy statement albums. It seems likely that there was more to the decision to move into releasing EPs and short LPs than just a simple consideration of “momentum”. Reznor agrees: “You can work on an album for two years and it’s judged, consumed, forgotten in an afternoon [laughs]. Then it’s onto the next Kanye West think piece. Which is, y’know, depressing for an artist. ‘Is anyone even listening out there?’

“We thought it might be an interesting experiment to allow the music to be absorbed in three doses. And then it took on a life of its own when we started down that path. This method has the added advantage of us not being able to go back and change the first part because we’ve committed to it. In a world of endless options it felt kind of daring to commit to going forwards because we couldn’t go back and change it. So that was the incentive behind it.”

Like Radiohead, NIN have spent a lot of time during the last two decades trying to combat the many headed hydra of the negative digital marketplace (listener malaise, over-saturation, exaggerated hype cycles, album leaks, illegal downloading &c.) mostly with a questionable degree of long term success. It especially feels like the options for musicians who wish to make themselves stand out in the short attention span, seen-it-all-before landscape of 2018 without doing anything ridiculous have become fairly limited. Even though it’s highly unlikely we’ll see Ross and Reznor sporting red MAGA baseball caps any time soon, perhaps if you were to argue devil’s advocate you could admit that you sort of see how this happened…

Reznor says that since the mid-noughties he has been “obsessed” with the idea of finding out what music fans actually want, so he can treat these desires with respect and “treat myself as an artist with some dignity” as well. Although all of these new dawn approaches were sincere at the time he now admits that they started to feel “stunty”: “There was the roll out of Year Zero on a major label that had money to spend on a storytelling device – an ARG or Alternate Reality Game – which was fine but it overshadowed the music because everyone ended up talking about a flash drive instead. And then there was the Saul Williams record…”

The rapper worked closely with Reznor (who was producer and advisor) on The Inevitable Rise And Liberation Of NiggyTardust! in 2007, and they gave punters the option of paying what they liked (with a suggested $5 fee) for a digital download of the album: “That record was an experiment in seeing if people would pay for music off their own bat in a way that felt sincere and the answer was not really – they don’t care.”

He refers to all of these experiments – including the release of Ghosts I – IV in a number of luxury versions including hardback coffee table book – as “interesting” but concludes that they were also “temporary”, ending up outdated just months later as soon as they were replicated elsewhere. He is equally as dismissive of the Kickstarter method for funding releases, for bands the size of NIN at least.

He eventually arrives back at my throwaway Kanye reference: “I came out of that phase more aware of other people getting involved in stunts than I had been before. In Kanye’s case however, one can’t be totally sure but it feels significantly more like the product of mental illness than a thought through move made by a provocateur.”

He says that while working in an advisory capacity for Apple Music since 2014 (and at Beats before this since 2012) he has come to acknowledge that streaming services are the future of music but still vents his frustration that the Spotify front end feels “more like a shopping mall record shop than a Rough Trade or an Amoeba. It’s not a place where people who love music are encouraging the deep dive into origins and history”.

His initial idea was simply that if you have access to all of the music in the world then wouldn’t it be “sexy and intriguing” to get lost down a pathway that had formerly been obscured to you: “I’ve often walked out of a record shop with thousands of dollars worth of stuff I didn’t think I needed – and I don’t need it really but I’m in love with music! So why can’t streaming services offer that kind of integrity and history. Yes, you can get today’s top hits but also you can go down a path getting turned on to totally new things.” But for the moment at least, he seems to have reconciled himself with the idea that currently the complete choice offered by streaming services is in part illusory. He says he has come out of the whole questing experience of the last few years “a little defeated” and has returned to seeing things primarily from the artist’s point of view rather than from that of the marketeer: “I’m a little bit less intrigued now by what I can do to stand out. When it came to making these three records it was initially a matter of, how can I light myself on fire so you will listen to this?” He pauses and laughs: “At least you got a good clickbait headline out of that question…”

He concludes his digital marketing overview: “But what we came up with in the end wasn’t really anything to do with gimmicks. It was more a case of: this is what we do; this is what we like; this is what we care about. And what we care about is: fidelity and music being the primary focus of your attention versus something I’ve said. Rest assured I’ll make some pretentious statements about the music but you can choose to listen to me or you can tell me to fuck off, it doesn’t matter. We’re settling into our mission now and we know exactly what that is: it’s less about mass culture and more about us acting with integrity, to lead by example, bitch privately and occasionally and not often and to the whole world.”

The album ends on the track ‘Over And Out’ which contains the lyrics, “Feel like I’ve been here before/ Over and over again” which appears to be postulating a deterministic view of the universe, one that denies free will. Addicts, by their very nature, are control freaks. When high functioning, they’re often either charismatic or highly manipulative. They’re not always great delegators. They’re not often that cool with letting the chips fall where they may. You could argue (and I do) that one of the most important stages in recovery is admitting you don’t have full control over your life and making your peace with that. As the ‘Serenity Prayer’ which is read out at the conclusion of most AA and NA meetings says: “God grant me the serenity/ to accept the things I cannot change/ courage to change the things I can/ and the wisdom to know the difference.” It might seem counterintuitive but actually admitting a lack of control can be an epiphanic and liberating experience. Certainly Reznor’s new found but hard won sanguinity about the digital landscape he continues to occupy and his relaxation of self-imposed rules about not revisiting old ground have, unexpectedly, resulted in creative rejuvenation.

As regards to a lack of free will he says: “That is what was going through my mind when I wrote ‘Over And Out’. I have read a lot of people suggesting that this is the end of Nine Inch Nails but not unless one of us drops down dead… it isn’t the plan for us to end now. [laughs] We feel particularly energised.”

As always it’s time to wrap the interview up before we’ve barely got going. NIN are not doing much press but they’ve got an appearance at Robert Smith’s Meltdown Festival in London to prepare for not to mention their own headline slot at the Royal Albert Hall over the coming weekend. It’s important to make the distinction that it’s Robert Smith’s Meltdown not The Cure’s. According to a source who works at the Southbank Centre, it would be an almost entirely different line up if it were chosen by the full band and in fact there is only one band the entire group can agree on: Nine Inch Nails.

Reznor looks at the floor and his voice drops to a near whisper when he says: “That is… very nice to hear.”

He is at pains to explain that his childhood in “cornfield” Pennsylvania kept him isolated from nearly all alternative music until he left home at the age of 18 and moved to Cleveland. But then suddenly, being able to access college radio which made his “head explode” with an introduction to about 40 different cult, underground bands all at once. This was his first exposure to a lot of music that would go on to cement what Nine Inch Nails were all about: “The Cure were one of those bands that really struck a chord and Head On The Door is the album that made them really important to me. I got into that and then worked my way backwards. That album got me through a lot of long dark times. I felt that this Robert Smith guy really understood who I was and I loved The Cure from that point on.”

While most famous people tend to differ from their carefully cultivated public personas to varying degrees, I have the uncanny feeling that Robert Smith leads a 100% authentically Robert Smith kind of life and Reznor does little to dissuade me of this notion.

There are people waiting outside the hotel suite now to whisk him away for food and then to a soundcheck but he settles back into the couch a bit and says, “I need to tell you about how I first met Robert Smith. It’s a longish story but I think it’s worth repeating…

“The way fame revealed itself to me was in incremental things – all of which had a significant impact on me. The first time I heard myself on college radio, it was, you know: ‘I can’t FUCKING BELIEVE IT!’ Then MTV played our video at 2am on a Sunday night and I was like, ‘Fucking FUCK!’ When we heard that we were opening for the Jesus And Mary Chain and Peter Murphy? It was like a dream come true. Seeing some guy at the back of the room in Tulsa Oklahoma screaming back every word of ‘Head Like A Hole’ at us because he had heard it somehow and it obviously meant something to him… that felt like the best fucking thing in the world. Anyway after a number of these incremental things I met Robert Smith.

“So we were living in New Orleans and we were fairly successful by this point; enough that The Cure knew who I was. They must have played in New Orleans that night. I think I was with the Manson guys and we were working on Antichrist Superstar and I’m sure we would have been high. We went to see The Cure show, we came back to the studio to carry on working and then all of a sudden people were calling me saying, ‘Robert Smith is at the gothic nightclub in the French Quarter and he wants to see you.’

“So it was about two in the morning and I came down [laughs] to this place called The Blue Crystal which is only about as big as this room. It’s the sort of club that no matter what time you turn up, they’re always playing ‘Blue Monday’ by New Order. I walked in and there is Robert Smith, all by himself dancing in the middle of the dancefloor but with a circle of goth girls all around him just watching him move. I walked out, he sees me and I see him and we’ve never met before but he just gives me a big hug. And we were just hugging for about two minutes and I think by the time we stopped ‘Blue Monday’ actually was playing. And we were just looking at each other and he was just [nods head slowly]. And that was it! My meeting with Robert Smith!

“But it was one of those moments where it felt like true validation in my mind.”

As coffee is being drained and coats are being put on I (perhaps slightly unfairly) blindside the NIN duo with a heavy existential parting shot and ask them when the last time they were in a situation where they had reason to think, ‘I’m not going to get out of this without death or serious injury’?

Ross is the model of English reserve, timing and delivery when he says: “As a middle aged father I don’t tend to get into those kind of situations any more. Let me see… I lived in New York just after the acid house period, just before I got clean and I won’t go into detail but I had some very… ah… well, I did have had a gun shoved in my mouth once. That was probably the most terrifying one. A more recent example was our flight from fucking Coachella to Vegas. I wasn’t sure we were going to survive that.”

Reznor nods: “I don’t know how typical it was…” He mimes a plane flying along and then dropping vertically before carrying on as before but much lower down. “Bassnectar was on the flight too. And I remember him sitting next to me and I wasn’t sure who he was at first. But when you have a near death experience on a plane, that changes everything. We may have been holding hands by the time we regained altitude. I never used to be conscious of it but now I’m aware that I’m in a flying tin can of potential death every time I step onto a plane.”

I tell them I’m not trying to unsettle them in any way but if I get on a plane and there are famous musicians on my flight I think, ‘Oh for fuck’s sake. It’s my time. I’d better text my girlfriend and tell her that I love her.’

They laugh because it’s the healthy thing to do. To laugh and accept all the things you can’t change, leaves you free to take control of everything else.

Bad Witch is out now