Back in the days before digital mobile technology, landline phonecalls could be surprising affairs. You’d pick up the receiver and be able to hear, faint and distant, the sound of someone else’s telephone call. As voyeur, you were presented with the moral question of whether to hang up, or else keep listening in to this unexpurgated, uncensored confessional. Generally, most of the conversations would be mundane, but the very act of listening in felt uncomfortable, with a strange and dark allure. It was this that Robin Rimbaud explored in his musical practice during the 1990s, when he used readily available technology to intercept telephone calls, redeploying these field recordings into his work. This can be heard to fascinating, unsettling effect on the Scanner 1 album, where conversations about sheep castration and work troubles hover alongside sex lines, sirens, and concert recordings over watery, unsettling rhythm and sonic constructions. It is like listening to London breathe. Recently, the Quietus saw a tweet from Rimbaud saying that the News Of The World phone hacking scandal reminded him of the time a journalist from the late rag called him up to try and purchase his archive of "found" phonecalls. The Quietus dropped Robin Rimbaud a (non-intercepted) line to find out more.

Can you tell us a little about how you first started using "found" calls in your work, and how the ‘Scanner’ name came about?

Robin Rimbaud: I’ve been recording since I was a fresh-faced teenager and had always incorporated recordings of school friends, family, people shopping at the supermarket, in offices, etc in my rather experimental recordings, using a little Sony recording Walkman. It was actually purely by chance I discovered this scanner device, since a friend was part of a hunt saboteur group and would use it to listen in to the local police. I immediately saw the potential and intrigue of being able to access these private spaces and incorporate them into these exploratory soundscapes I was producing at the time. I was especially drawn to the fact that the recordings were so intimate, so clear, yet abstract in nature. One had to imagine who these people were you over overhearing, where they were, what kinds of lives they led, although the nature of their conversations often clearly explained this. As such using the device immediately suggested the artistic name of Scanner. My joke remains with friends that if I’d have continued using tape recorders in my creative work I would now be known as Robin Rimbaud – Tape Recorder, which doesn’t quite have the same ring about it!

What interested you about the idea of listening in?

RR: It’s curious that when I was a teenager I’d recorded crossed lines on our ancient analogue home phone so this felt like the next step. Incorporating them into these cinematic dark landscapes of sound seemed to just make perfect sense. Also at this time the chill out rooms in clubs were growing in capacity and my work was being played out there. This offered a very human aspect to digital techno music by incorporating the voice into the electronic atmosphere. It was partly about humanising something that was very difficult or ‘other’ to listeners at the time, so to use often difficult abstraction sound experiments alongside more recognisable human voices seem to make perfect sense, and could easily seduce the listener into sonic worlds they might not otherwise have experienced.

What equipment were you using? Was it readily available at that point? Was it the same gear as the NOTW were using in the early days of mobile tech?

RR: To begin with I was using a Four Track Fostex tape deck that allowed me to mix up to four layers of sound together as well as the radio scanner and a few other simple EFX units. I still remember Richard James/AFX remarking on the use of a particular echo unit at the same I was using and us nerdishly chatting about the possible settings for this! It was very basic. Then he went out and bought a radio scanner and used it on several recordings, including a sadly unreleased phone prank he played on me and Mixmaster Morris at the time. The scanner was readily available at all hi-fi shops on the high streets, they were being sold to listen to pilots at airports. Remember at this time, that’s the early 1990s, that these conversations were overheard on the analogue network as all mobile networks still used those for these rather insecure transmissions. The radio scanner was merely a rather more sophisticated radio receiver that offered a wider spectrum of possibilities. Today it is a digital network and far more secure, and indeed the News Of The World were not exactly doing anything clever, merely dialing in the phone numbers of public figures and guessing at their security codes to collect their voicemail. They couldn’t, as I was doing at the time, listen in to complete conversations between two people. Their access has been a very one-sided, one-dimensional invasion into privacy.

How did you as an artist deal with the moral question of listening in to calls, and then using it in your work?

RR: I certainly wasn’t the first nor shall I be the last creative person to use such ideas in their work. In making the work and engaging in debates about the morality of such work I learned much more about what was deemed to be right and wrong. Curiously anyone critical of such an approach immediately became a voyeur once the scanner was switched on picking up live conversations. These ‘found/stolen’ voices brought into focus issues of privacy and the dichotomy between the public and the private spectrum.

Remember too that this was before the internet as we recognise it today was available, email too was still in a very early incarnation, and as such questions of public and private space around this new global network were in their infancy. In some ways the work anticipated our fascination today with the banality of others, the lives of other individuals who have little to offer but a fleeting nod towards success, these television shows and magazines that reap reward from people fascinated by the idea of entering these ‘private’ worlds. It’s very important to remember that these are all entirely mediated today, everything, as truthfully as it may be presented, is often scripted, edited for content, and so on. There are outtakes of the Ozzy Osbourne MTV series where he has to repeat various lines for the camera for example. The original scanned conversations were the raw data, drawn down from the airwaves. They presented real people in real situations, not censoring themselves, as true to themselves as they wished to present privately.

How did you decide what material to use, and what was not appropriate? How did you select what to record?

RR: I would record everything as soon as I switched the scanner on. It would always be such that the most intriguing conversations would only happen when the record button wasn’t engaged so I learned from that. I was very clear about what to use, removed names and addresses on recorded material, edited out identifying materials, pitched changed voices and so on. I was interested in the raw conversations so wanted these to remain transparent.

Did your approach change over time, due to moral or other concerns?

RR: I followed this flow of work for some years, in both performance – picking up live conversations in the air as I stood on stage (a favourite being broadcasting the details of a ‘private’ Jah Wobble party at the Phoenix Festival when I played there in 1994) and in recordings. However as time passed other interests took my fascination and especially after September 11 it became ever more difficult to travel with any equipment that might be deemed to be used for subversive purposes. There was the story at the time of some English plane spotters all getting arrested in Greece for using radio scanners to listen in to the pilots, so what was once a naive hobby became a dangerously subversive illegal act in the eyes of the police force. It felt better to retire the idea and not spend my days trying to argue what purpose the scanner served for airport security staff.

How did the News Of The World approach you? How had they heard about you?

RR: There had been a South Bank Show Special on my work around the time, as well as features in The Guardian, The Independent, and even a rather insubstantial film based upon the concept of my work starring Minnie Driver (High Heels and Low Lifes) so clearly they had a rough idea of what I was doing, at least the salacious side of things. At the time I had an office in London and they got in touch with me there. They left a message requesting me to get in touch with them. I clearly knew why they would be getting in touch. I left it for a few days. I was confident I had no interest in profiting from these works in this way. After a few days I went to a phone box and called the journalist back. I had seen too many spy movies to know that it was essential to call from a relatively untraceable number. As he excitedly began to speak to me I hung up. It was a deliberate ploy to annoy and frustrate him. A few days later I repeated the exercise. Childish as this may seem I wanted to at least play with the drama of the situation. The journalist explained that they were interested in any recordings I might have of celebrities in conversation, of any famous people that I had caught in compromising situations. Indeed if I had had such recordings I would never have done anything with them anyhow but didn’t want to tell any more to him. I remember playfully speaking with Marc Almond at the time and trying to conjure up some fake calls so we could sell those and profit from them but of course we never followed this through.

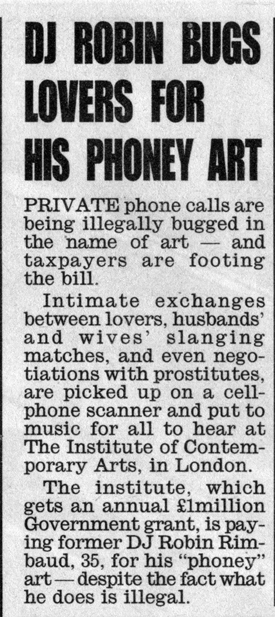

Curiously then the Sunday Mirror published a piece on my work since I also would not respond to any requests for interviews or details to them, and published the most absurd tale, full of mistakes. Great headline though.

What do you think their motivation was?

RR: I think then as it is now that these newspapers often trade on the insecurities and revelations of others. It’s hardly journalism as we would recognise it, but it’s obvious they were interested in exposing and exploiting others as is often their key goal. It’s more entertainment than news. They wanted to buy recordings off an independent artist who was attempting to at least do something arguably more interesting and vibrant with them and then print them in their newspapers for profit.

Did it make you think differently about what you were doing?

RR: Absolutely. The feeling of an unsteady gut guilt began to hover. There was the thrill of the major press ‘interested’ in me but it was merely a surface interest from a journalist that was willing to pay me for something that I would never use in my own work let alone share with someone like the mainstream press.

Has it all been stirred up by the recent News of The World phone hacking scandal?

RR: I am struck by the short-term memory of how the press operates. I have resisted speaking about this subject until now actually, indeed haven’t spoken publicly at all about NOTW until I heard of how abusive and disrespectful they have acted towards so many countless individuals and it seems that the list of those invaded continues.

Would you now be wary of using such methods in your work?

RR: I have never consciously shied about from such subjects or censored myself but to interfere to such a level of privacy and exploit people in such a way is one thing but then to deny it all is the worst aspect of all to my sensibilities. I was always quite open, honest and principled about what I was trying to do, and how I was operating in a professional field of creativity.