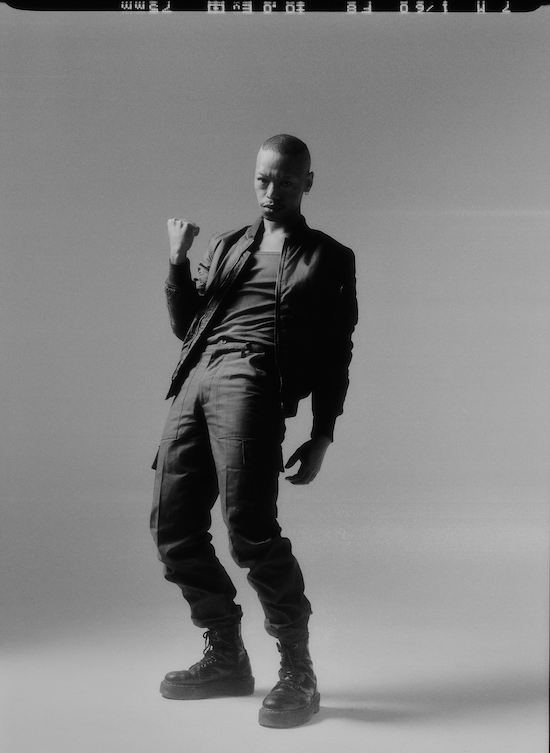

Photo by Alex de Mora

It’s the week before the Christmas lull when Nakhane joins me for our Zoom conversation, just a few days before the release of their latest EP, Leading Lines. I’ve spent the preceding morning with the EP, talking in all that the South African musician, actor and novelist has to say. Our conversation extends all of those musical conversations far beyond a song’s three minute mark. After all, queer always has something to say.

“The music that everyone’s hearing now has been ready for so long,” they tell me, noting that much of it came before they identified as non-binary. They speak slowly, with care and enthusiasm. “So, now, when I listen to the songs, some of the, “gendered characters” in the music, I wish they were less binary. But it is a product of the time when I was writing it. That’s queerness I suppose, it influences everything and nothing.”

Everything and nothing is a concise description of ‘queer’ as a process, or a state of being. Any understanding of queerness within popular music will touch on both absence (blacklisting, violence, erasure) and presence, both in the literal form of queer icons and the undercurrent of queer that passes through the music and fashion of the 80s and 90s, for example. Nakhane’s awareness of those that came before them runs through their music, taking heavy inspiration from the slick, glittery guitars and synths of the 80s and combining this with heavier, club-ready sounds.

“For me, queerness is seeing a new perspective, seeing things from a different way. And not necessarily answering things but experimenting”, they tell me as their eyes light up. Queer has always upturned, unseated and is “always forging forward, or left!”, they say – tying together the existence of their work with queer theory at large. Their analysis quietly reminds me that they see themselves as part of something larger.

By that definition, Nakhane’s work is delightfully ‘queer’, easily imbuing the upbeat grooves of South African house and dance music with emotional weight, before swinging that weight over their head with flurries of wit and charisma. ‘Tell Me Your Politik’, a song about regretting having sex with someone with differing political views, exorcises personal demons while showcasing Nakhane’s intriguing balance between dark and light – backing the line ‘everyone is a murderer’ with big, wide basses, synth swells and handclaps. It’s music that doesn’t mind chewing up convention before spitting out something entirely different.

“I believe that everything is political, because politics is about people. I walk into a hook-up and people already have an idea of what I’m going to be doing or what they think I am, sexually,” They tell me frankly. Politics does not bleed into their music as much as it is its basis; the two are not disentangled. Their music has been laden with political themes, which often revolve around Nakhane’s own personal experiences of homophobia and queerphobia during their upbringing in South Africa, after they were outed. Despite the repression they felt, they remain aware of the freeing aspects of queerness.

“If anything, we’re saying that everyone should be able to do whatever the fuck they want, as long as they’re not hurting people.” The rejection of this freedom is a point of curiosity. “Why is that freedom so scary? That’s that freedom I’m after, artistically, personally, romantically… I’m interested in that hunger for experiencing, hunger for openness, hunger for finding something else!” Their eyes are alight again. “So many people I love lives have been thwarted because they felt like they couldn’t do anything, because the consequences are so dire.”

As much as queer drives forward, it also finds itself tangled up in its own history – just like Nakhane themselves. I ask them how they’ve been since they moved to London five years ago. History can also be baggage, and its duality as a place of comfort and pain becomes clear. “Every piece of work that I make, every song that I write carries with it inchoate… relationships, things I haven’t dealt with properly. Things I haven’t closed, things that still need closure! – I guess maybe that’s why I write about it,” they say. “So it’s very multifaceted, and then on the other hand, it’s very simple – it’s just a song”

London is where Nakhane’s last full-length project, 2018’s You Will Not Die was conceived and shaped, and while the move granted Nakhane some comfort in anonymity, they found that their experience in a new environment was marred by the presence of British racism – and the impossibility of ‘escaping’ as a Black person.

“I’m always in the place of rage about this country. But then, I’m in a place of rage everywhere I go, as a Black person, particularly as a Black queer person. It’s like that interview with James Baldwin where someone says, ‘A lot of people in America think that you’ve gotten away… you’re free now, because you’re in France" and he says, "Where is a Black person free?" – there’s nowhere that I can run away to that my blackness won’t confront me.”

As they land on their point, and I collect myself to speak, Nakhane politely interjects. “There’s so much rage – I felt before couldn’t write music like that, and I thought, well, you can write music about anything.”

Rage is a central part of Nakhane’s new music, both on Leading Lines and their upcoming album Bastard Jargon, which is due on 3 March. They understand rage not necessarily as an expression of erraticism as much as an internal reflection and affirmation, but they are sure to balance both in their songs.

“My rage isn’t going around there with a flamethrower destroying things, though, sometimes it’s necessary! But my rage is an awakening, it’s a consolidation. You’re allowed to be angry, because people like you have been made to feel like they are not even human beings every day”

Who better to harness this rage, and balance it with the euphoria of the dancefloor, than Nile Rodgers? Despite Rodgers’ status, Nakhane was in no way intimidated by their collaboration. Luckily enough for me when he was a sweetheart, and always used to say that I’m here in service of you and your music. Initially, I was like, ‘Yeah right!’ you know? But he was surprisingly humble. He never made a decision without running it past me.”

Given the emotionality of Nakhane’s music, their ability to pull from the past and look to the future – you’d expect that they’d experience fatigue from releasing music that often touches on personal trauma. “Whenever I’m like, ‘Oh, I’m so tired’ my mum says to me, ‘Don’t forget, you chose this!’ and that’s such a sobering point of view. Ok. Great. So that’s my burden. So what am I going to do to make sure this doesn’t destroy me? To make it sustainable for myself so I can be here in 30 years’ time and look back… and be proud of that 34-year-old who released it.”

They exercise, don’t drink, and look after their body and mind as much as they can. They recognise that the community that surrounds them often acts to remind them of their ability, worth and potential. The importance of community is central to both Nakhane’s musical collaborations, and their personal life. “When I am depleted, I understand that I’m still loved and I am lovable. I’m still worthy of being here. I’m still worthy of being an artist.”

Nakhane is still here, and ultimately, they are unfinished – and not to their detriment. I remark about trying to cram a kaleidoscope of emotions into a three-minute track, and their lack of sentimentality and strong queer desire to forge forward shines through. “I always say to my best friend, ‘That’s why we make another one’ – that feeling like you’re not really finished… I’m not particularly precious about those things because I’m gonna write another song! Because there’s a shitload more things I still need to talk about or write about. They may not necessarily all be personal, but they’re all going to carry a little bit of me.”

Nakhane’s new album Bastard Jargon is released 31 March via BMG