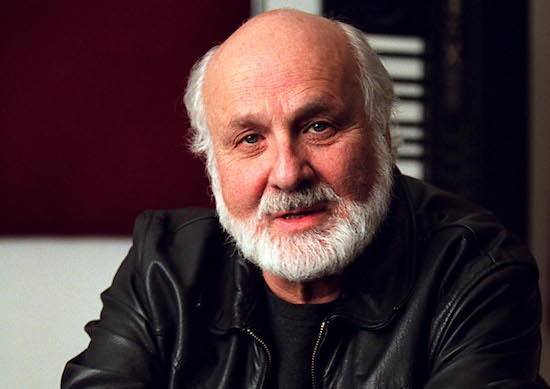

In 1961 Morton Subotnick had a vision of the future. "I did a piece," he tells me via Skype from his apartment in New York, "which I thought of as what would happen on the stage 100 years from now." He could see the world around him was changing. Since the Second World War, cheap electronics had become pervasive. Subotnick could see that music – and not just music – would be affected by this "in the same way that written language had when the printing press had been created".

The piece he presented in San Francisco that year was meant as a vision of what would become normal "after generations of people growing up with this technology". It was written for two stereo tape machines, their four speakers surrounding the audience, along with four musicians and a series of theatrical lighting flats upon which different coloured lights and images could be projected and controlled by hand. Towards the end, Subotnick’s friend, the poet Michael McClure, read some verses from his work, ‘Flowers Of Politics’.

"The review came out and said something like, ‘A new art form has been born!’ So I thought, oh, well maybe I have an aptitude to do something. So I decided, I’m gonna work on it and perfect this thing. It may take me ten, 15 years. I don’t know. And then I’ll stop and do something else. I stopped in 1993. I finished it."

On Saturday, Subotnick will perform live at the London Contemporary Music Festival, alongside works from his old colleagues at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley and Tony Martin. Subotnick founded the centre with Ramon Sender in 1962. Until 1967 it remained a pioneering artist-run centre for electronic music and experimental performance. "It was like the Kitchen," Subotnick recalls, "except it had an electronic music studio." It also hosted performances by the likes of Steve Reich, John Cage, the poet and playwright Robert Duncan and the Anna Halprin Dancers’ Workshop, to name just a few. It was also at the Tape Music Center that Subotnick and Donald Buchla put together the world’s first analogue synthesiser (there’s some debate as to exactly what came first, the Moog or the Buchla, but Bob Moog himself always maintained it was the Buchla, so I’ll defer to his judgement).

Later on, Subotnick might just have been the first person to get a club full of people – including the entire Kennedy family – dancing to purely electronic music when he played his Silver Apples Of The Moon at the opening night of New York’s legendary Electric Circus. "I mean, I knew it had a beat," Subotnick recalls, "but I’d never heard of people dancing to that."

Suffice to say, if you’re interested in electronic music, you’ve got plenty of reasons to be grateful for Morton Subotnick. He pretty much wrote the book (actually, the book – the one he’s been writing for MIT Press for the last three years – isn’t quite finished yet, but he’s hoping to polish it off in the next couple of months). But for Subotnick himself, that path began at the very beginning of the 1960s at a little jewel box theatre off Union Square.

For most of the ’50s, like most of his peers on the West Coast at the time – La Monte Young, James Tenney, Terry Riley and so on – Subotnick had been composing in a style influenced by the twelve-tone technique of Arnold Schoenberg and his students. "My own version of post-Webern," he calls it now.

A clarinetist since his childhood, when a doctor prescribed taking up a wind instrument as a cure for a persistent cough, by this point he was playing for symphony orchestras and composing for TV, theatre, dance or pretty well anyone that would ask him. "I just wanted to write music," he tells me. "I loved blank pages and then putting lines on it and it would turn into sound. That was magic to me. And if I could make a living doing it, I would do it."

One day he got a call from Herbert Blau, director of the local Actor’s Workshop. They were doing a new version of King Lear with scenography by Robert LaVigne and a 26-year-old Michael O’Sullivan in the lead. The whole thing was going to be "apocalyptic", Subotnick recalls: "It was going to take place in a kind of primordial humanity and the sets and the costumes were made from seashells." The company were looking for "a wild composer" and Subotnick had been recommended as just such a man.

"I thought, I don’t want to write incidental music for a production like this. So I recorded Michael – Herb directed him – the way he was going to do the storm scene, a year in advance. I recorded it and made all the music from his voice. I cut and pasted and upside down and backwards, fast and slow. It took me almost a year."

"But that’s how I got there," he continues. "It was working on this for a year, I realised something that I had not thought of before then, which is that I really didn’t like being on the stage. And I thought, well, this technology could create a new paradigm, a new environment for composing. It would be like painting. You would be composing music as a studio art. I made the decision at that point that this new technology was going to allow for everything to be different. A new kind of composer."

The twin quests that Subotnick had set himself upon at the beginning of the ’60s would finally reach their goals in the early ’90s. The "new art form" that he had glimpsed with his work of 1961 for tape machines, instrumentalists, lighting flats and McClure’s poetry found its fulfilment in Jacob’s Room, a chamber opera first performed in Philadelphia in April 1993, with four cellos, synthesisers, electronics, visuals by the legendary video artists, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and Blau as its director.

Around the same time, he produced the first in a series of educational CD-ROMs that allow users to ‘paint’ musical gestures with the movements of their mouse across a computer screen. Making Music was simple, intuitive, elegant and enormously successful. "Silver Apples was my famous big hit, but Making Music was my really big hit," he tells me, "which I actually got money for." But quite apart from allowing the composer to finally put a down payment on an apartment, Making Music realised the vision he had nurtured for 30 years: of music as a studio art, a compositional interface as plastic as a painter’s easel.

For anyone else, that might have seemed like some fairly major life goals unlocked. But something was still nagging at Subotnick. "I realised that I didn’t have a model for just live performance. I didn’t think of performing electronics." And here was New York’s Knitting Factory on the phone again, pestering him to come and play a gig.

"They kept calling me on the phone and saying, we’d like you to come and play. And I said I don’t do that much anymore. But they kept calling me and I finally got angry. I said, ‘Why are you calling me? You’re doing all this pop stuff, do you even know what I do?’ And he said, ‘Oh of course, we know everything you’ve done.’ I said, ‘You do?’ So then I had to come up with a new model, a new technique [for live performance]."

For a long time Subotnick had eschewed live performance. In the ’60s and ’70s he had tried mixing tape with live synthesiser, trying to get a jazz-like spontaneity out of the tape medium. But in the end, the technology just couldn’t keep up with him. "It was fun," he says, "but it wasn’t really what I was after. So I put it away." The persistence of the Knitting Factory’s bookers finally persuaded him to pick it up again.

Subotnick’s live shows these days involving wiring Buchla’s latest 200E synthesiser up with the Ableton Live software package. "I could do everything with analogue," he insists, "except you can’t have enough equipment on the stage and you can’t get your hands all over it." By duplicating the Buchla’s oscillators with the software before sending them back through the synth he can improvise freely with a constantly changing blend of old and new material, samples and extemporisation. "It’s really getting pretty versatile at this point," he tells me. "I feel I’m really close. Another couple of years and I’ll finally get to what I thought was gonna end in 1980. But I’m getting there."

After we’ve been talking for quite a while, I finally ask Subotnick what I’d been wanting to ask from almost the beginning of our conversation. In 1961, I say, you had this vision of what music might be like a hundred years in the future, but are you still thinking of what music will become a hundred years from today?

"No," he sighs. "I stopped worrying about it. But I don’t think the hundred years was too far off. What I didn’t anticipate was how strong popular demand is on the slowing down of certain aspects of social life. We no longer can easily distinguish entertainment from fine art. There’s nothing wrong with popular art, but what’s wrong with that being equivalent to fine art, is that they produce it because people like it. It doesn’t push the envelope – it pushes it as people like it pushed.

"I thought everything was going to happen fast," he continues, "And everybody believes it has happened fast. But the weight of popular demand slows things down from changing, that makes it very difficult for us to move.

"The best example, I suppose, is the typewriter. Originally it was getting stuck, so they built a typewriter that you couldn’t write fast on so it wouldn’t get stuck. And then that keyboard, that was created so you couldn’t type fast, we’re gonna go to Mars with! It doesn’t go away! IBM tried to make one that was logical. No one wanted to buy it. So popular demand has held back that technology. And we’re ready to go to Mars – in spite of it, but with it. It’s an interesting problem. So that’s the way I think about the future."

Morton Subotnick will be at the London Contemporary Music Festival at Ambika 3 on Saturday, December 12, as part of their West Coast Night, performing a solo Buchla set and the UK premiere of his 1965 composition with Tony Martin, PLAY! No. 3; for full details and tickets, head here