Let’s be clear – any album entitled Suicide Songs better be fucking good. In the UK, suicide is the biggest killer of men under the age of 35 – a truly shocking statistic – and the vocabulary surrounding the subject weighs heavily and hits hard.

Suicide Songs is the title of MONEY’s second album and is, thankfully, a magnificent record and one that is both emotionally direct and unflinching in its imagery. It is more than a worthy follow-up to their 2013 debut The Shadow Of Heaven. The track ‘Suicide Song’ may well be the most beautiful song you will hear all year.

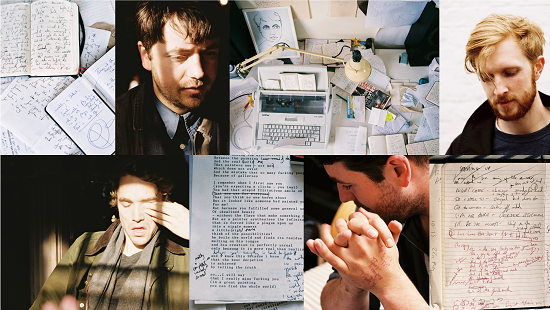

The chief protagonist in the world of MONEY is singer Jamie Lee. Jamie describes himself as a poet – he recently sent me a particularly beautiful example entitled ‘Here’s To The Dead Boys And The Laughing Prayer’ – and a songwriter, and Suicide Songs was written during a particular bleak and disruptive time in his life.

I first interviewed Jamie for tQ two years ago. We sat in a Manchester pub and Jamie held court. He was a charmer – interesting and interested – and it was hard not to warm to his coquettish charisma. He wrote a poetic soliloquy in my notebook while I’d nipped to the bar and regaled me with tales of debauchery that I only half-wanted to believe. But, amid the showmanship, I sensed Jamie was self-aware enough to know that not everyone would fall under his spell and that MONEY’s music could be a little bit ‘marmite’.

This time we conduct the interview in the back of a tour van, MONEY having just arrived in Manchester after the previous night’s London show. Jamie is joined by bandmates Billy Byron and Charlie Cocksedge. Charlie doesn’t utter a word during the interview, but both he and Billy seem fraternally protective of Jamie as we discuss the difficult backstory to Suicide Songs.

At one point, there is a rap on the van’s window and one of the sound guys asks whether we are having a party. We aren’t – discussing the period of Jamie’s life during which he nearly drank himself to death is definitely not conducive to a shindig. Jamie himself is less gregarious and more introspective than when we last spoke, and he tells me “that’s because I am not drinking.”

Lifestyle changes aside, MONEY, of course, still don’t do things by halves. For their hometown ‘Manchester’ gig, they’ve decamped to Salford and an inaugural show at the mysterious White Hotel. The venue’s location is revealed only in the hours before the gig and turns out to be a disused warehouse on a dystopian industrial estate. The venue is a marvel – a handout maps out the whitewashed space, which includes a pop-up cocktail bar, another bar in a pit and, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, a spanking bench.

The gig is genuinely magical. The band add a cello and violin to their live sound and Jamie is utterly mesmerising as he rips the words from Suicide Songs from his pulsing heart. From the opening strum of ‘You Look Like A Sad Painting On Both Sides Of The Sky’ to the magnificent closer, ‘A Cocaine Christmas And An Alcoholic’s New Year’ (a song that goes toe-to-toe with The Pogues in the ‘harrowingly maudlin Yuletide ditty’ stakes, and for which Jamie introduces as “all in the past”), there is not a smartphone in sight or a distracting chat to be heard – just an audience stunned by a mixture of brilliant musicianship and brutal honesty.

After the show, Jamie and I stand outside in the evening murk and discuss the relative merits of writing ‘happy’ or ‘sad’ songs. Our unanimous view is that it’s easier to write sad songs, such is the vast human capacity for pain and sorrow, as long as there is the faintest sliver of hope. Suicide Songs may well just be a masterpiece of that particular craft.

Jamie, I believe you moved back to London to write the new album. What was wrong with my fair city?

Jamie Lee: Manchester had become too distracting. I felt like I wasn’t focussing hard enough on the actual craft of writing. I need to work at it and I am a very lazy person. I needed to lock myself away in order to focus. I wanted to be a better songwriter than I was on the first record, and I wanted to provide better songs to the band and to myself. That was the reason – I wanted to write good songs.

How was that for the band – having you working in a different place?

Billy Byron: There was a difficult point where Jamie came back up to Manchester and we were trying to get the music together, without knowing what each other was doing. Originally, the band was the three of us in a room together, which would take ages to write stuff. That first record was a product of the songs going through many versions and we would end up with versions that we weren’t even necessarily happy about. That way of doing it didn’t really work for us. This was us trying something different, with Jamie writing almost complete songs in London. Then we would come back together and piece everything together.

Did that ever make the new songs feel like a Jamie Lee solo record?

BB: I want Jamie to do a solo record! No, it feels like MONEY but entering the process felt very different. For me, it feels like this is ‘day one’ and I feel we finally know our direction. It was easier this time and next time will be even quicker. We have taken quite a long time over these first two records, but I feel like we could now knock one out tomorrow if we wanted to.

JL: [Laughing] Yeah, bruv.

Charlie Andrew produced the album. What did he bring to the process?

JL: Some sanity and some structure. He gave us a framework to realise the disparate ideas that we had.

BB: He should be a professional mediator.

If I can turn to the themes running through the record. You’ve spoken about wanting the album to sound like it was “coming from death” – can you explain what you meant by that?

JL: It is a very difficult thing to talk about. There was nothing aspirational about it, apart from being completely honest about the content of the songs. I wanted the album to sound like it was immaterial. My whole thing about art is about making the immaterial things seem more important than they are. In terms of the album “coming from death” – death is a place of immateriality, if that’s a word.

I’m not quite understanding your motivation – why did you have a desire to explore such a concept?

JL: I don’t know, maybe I have a morbid curiosity about thinking about death and that is common in the writers that I like. I felt it was my job as an artist to think about life in terms of its bookends – what it means that we are only here for a moment and then we disappear. Maybe for the period of these songs I became slightly obsessed about this idea.

How did that obsession manifest itself?

JL: Well, I would drink to the point that I didn’t necessarily care – or it felt like I didn’t care – about my own life or anything. Maybe I did care, but less than I ever had before. How much of that was an obsession or whether it happened by accident is hard to judge.

I am sorry to push you on this, but I’m interested as to why an obsession with death would lead you to drinking excessively.

JL: I have always been curious about people and I am always talking to people. You can find people in pubs and if you like to drink then a pub is an endless resource for meeting people. If you start to enjoy it too much you can become an alcoholic and then you don’t know why you started in the beginning. You just know that you do it and it is very difficult to get out of when it becomes excessive and chronic. I don’t know if I was a chronic alcoholic but I was definitely excessive. You get confused as to why you were in that cycle and you find yourself nowhere.

I am happy to hear you seem to be describing your experience in the past tense. Is that the case?

JL: Yes. I am trying to stop that behaviour now, because I don’t want to do it any more. Part of the reason I can do that is that this record is about to be released, we are starting to play live and we have a purpose together. I hope I can say goodbye to that period of my life. I already feel much better. If you have ever suffered serious alcohol withdrawal, you are in a living hell. I read John Doran’s Jolly Lad and could relate to what he went through. Everything is horrifying. It was a very strange experience and pretty terrifying. So, there isn’t a story behind the album’s creation except for being times when I thought I would drink myself to death. And I didn’t care. I was enjoying it. That is a very unhealthy place to be. That’s mad.

You say there isn’t a story, but the album title is very evocative – why call your record Suicide Songs?

BB: The title felt right for the record. We didn’t think of it in terms of seeing it written down or how people would react. It wasn’t a provocative thing and it is only when friends have seen the imagery and the title and then said, “Wow, why have you called it that?” have we realised its impact.

If I may challenge you a little – the words are very impactful. One of my favourite songs on the album is ‘Suicide Song’, which contains the line “This is your suicide song.” Surely, that is a very strong statement to make?

JL: That song was written very quickly about a friend and I think that although I hadn’t been very well myself, I found myself actively wanting to protect my friend with this song. I felt that an act of resilience in me, even though I felt the same feeling as the person I was trying to help.

Did you ever worry that people would misinterpret the lyrics in some way?

JL: Maybe. I think artists have paradoxical responsibilities. They have a moral responsibility to realise the power of what they put out and how it can influence people that listen or read their art. However, there is also a necessity for them to be truthful and honest and those two responsibilities don’t always match up.

How do you try and get them to match up?

JL: How do I get them to match up? Well, the song ‘Suicide Song’ is me trying to be objective about the topic. Maybe my response to that topic is not exactly a clear message – or it is a dual message – and maybe that shows more about the state I was in, with regards to a disinterest in life and what I thought other people thought about life. Of course, if anyone suffers from anxiety or depression or feels that life is hopeless or that their life has no meaning, then they should talk about it. I am finding that more and more of our friends are opening up to us and talking about these things. I think finding things difficult is something a lot of people go through and there is hope, as family and friends, or whoever, can help.

However, in terms of art, I always wanted to make something that doesn’t shy away from worrying about the potential negative implications of what I say or do. Actively I don’t want to hurt anyone and I do worry sometimes about the moral implication of what we do as a band. But, at the same time, it is not up to me to cover every possibility of how a song could make someone feel. That is not my responsibility – fortunately.

If it was, you’d never write a song.

JL: Exactly.

Do you worry about going too far with your art? I am thinking about the poem you posted on MONEY’s Facebook page a few months ago, entitled ‘Sucking An Old Man Off In The Pub’.

JL: [Laughs] I think my telling of that story is quite tender, actually, and quite humorous. I wanted it to be a piece of literary terrorism. I wanted to shock other writers – not the readers – because I feel many young writers are not taking enough risks. Maybe I did cross a boundary.

So, reflecting on what we have just discussed, how was last night’s gig? How emotional is it to perform the new songs?

JL: My sister and my girlfriend were there last night. They know exactly what has happened over the last two years, and they started crying during the gig. I saw them and almost burst into tears myself but managed to compose myself. I don’t know what the value of this record is, but I know it is an honest one. I don’t know what the price to pay is for making it, but I knew I wanted it to be the best songwriting I could produce, even if I had to disrupt myself to get to that end.

Billy, Charlie – how was that for you, seeing Jamie going through that process of ‘disruption’?

BB: In some ways, it is a miracle we are here today playing these shows. Yesterday’s show felt like a clearing of air. The process of getting to that point was long and painful and, luckily, we have a manager who is a great friend to all of us and has kept us together. I don’t want to be too dramatic, but it is really down to him that we are still making music together. It definitely wasn’t easy, beyond the content of the songs, just trying to reset the band. And, you can never really fully reset as there are always cobwebs and always the past.

I have two final questions – one semi-serious and another slightly impertinent. Firstly, can you imagine a glorious world where ‘A Cocaine Christmas And An Alcoholic’s New Year’ is the Christmas number one?

BB: That song coming together was a fun moment in the studio. It came out of nowhere and the imagery was great. We have talked about a video edit for it – it would be fucking ridiculous. We could go head-to-head against The X Factor song. That would be hilarious. We could get it played in all the shopping malls.

JL: My mum would always say, “Jamie, why can’t you write this year’s Christmas number one and we can all go on The X Factor.”

Finally, are you aware that MONEY are quite divisive? Some people think you are the Second Coming, but you do get an opposite reaction as well. I had someone once tell me that MONEY sounded like “Coldplay gone wrong.” Do you care about stuff like that?

JL: The further we go, the more music we make, and the better we get, then the less and less I care. With the first record, we didn’t exactly know what we were doing. You put out a piece of work, which you don’t think is 100 per cent of what you can achieve, and when people judge you on that it is a really empty feeling. That feeling motivated all of us to make this record and is probably why we have taken so long. But, I wish we did sound like Coldplay. That’s what we are going for.

The album Suicide Songs is out on January 29th via Bella Union. MONEY play a UK tour in February