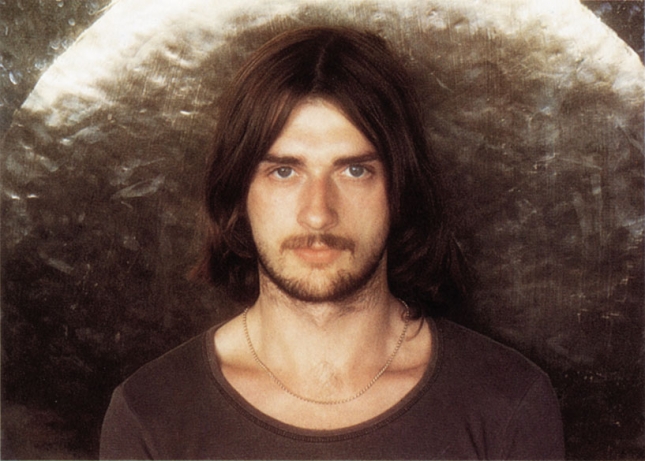

Few rock & roll careers have managed to be both as strange and as successful as that of Mike Oldfield. After his 50-minute, nearly all-instrumental prog rock odyssey Tubular Bells launched Virgin Records and somewhat bafflingly reached number one on the UK album charts in 1974, he has continually thrown convention to the wind with each successive release, and has yet to really be punished for it with a serious dip in commercial success or critical acclaim. With everything from the boundary-pushing electronic folk of Hergest Ridge to the full-on classical sophistication of Music Of The Spheres, Oldfield has never been one to resist change or shy away from experimenting with new things, but he’s also managed to maintain a level of consistent success usually reserved for somewhat safer artists.

Presently, Oldfield is in the midst of the tall task of remastering and reissuing his entire back catalogue in chronological order. The latest in that series is a new edition of Incantations, his 1978 masterwork that remains his only studio double album. The rerelease is packaged with a new 5.1 mix of the album, a live DVD of the 1979 tour supporting it, and ‘Guilty’, his infamous 1979 synth-driven disco track perhaps rivaled only by McCartney’s ‘Temporary Secretary’ in both its unmitigated embrace of a relatively new form and its bold rebranding of an English pomp-rock icon. Unlike Macca, though, Oldfield’s flirtation with electronica wasn’t a flash in the pan moment for his career; it was merely one of many experiments he would try (and continues to try) in his lifelong defiance of labels.

Oldfield spoke to us from his relatively new home in Nassau about the remastering process, early synthesizers, and, inevitably, Tubular Bells. Today, he’s humble without being incognizant of his considerable legacy, but more importantly, he still has his eye fixed right where it belongs – on the future.

You’re in the Bahamas now, is that right?

Mike Oldfield: That’s right.

How long have you been living there?

MO: A couple of years now.

Do you find the environment there suitable for songwriting?

MO: Hmm, yes.

I only ask because with your early material a sense of place was always such an integral part. Hergest Ridge was not only evocative of where you lived but named for it, so will we be hearing the Bahamas in future Mike Oldfield recordings?

MO: Yeah, possibly. You know, maybe I’ll try to use some local talent. I’m still settling in a little, really.

Talking of your older material, we’re having this chat because you’re remastering the early stuff, and the Incantations re-release is coming out imminently. You’ve been handling the remastering yourself, what have you been doing with the recordings exactly to brush them up for these releases?

MO: Well, where they exist, I get the multi-track tapes sent over in digital form. With Incantations, we didn’t have all the multi-tracks for various reasons. They’ve been passed around different libraries and different record companies. In those days, there was no requirement to even keep the multi-track masters, so it’s just luck whether they still had them. And that’s if they’re in any good condition still, because of oxidization of the tape. So there weren’t all the masters for Incantations. But I did discover some outtake tapes, and I discovered some interesting little things on there.

So I get those and take them to my home studio, and my home studio is like a professional studio now with Macs and ProTools and things like that to see what I can do with them. If I get a new idea, I make a new version, or remix it in 5.1 if I have the multi-tracks. They’ve already been remastered but that doesn’t really mean much. It just means somebody was sitting there and playing with the sound a bit. It’s the new versions and the 5.1 mixes that are interesting.

Has it been more personal to be able to have your hands on the final product that’s about to go out?

MO: Well, I always did do that, really. Even in the Tubular Bells days when we put the final mix down, even though I was learning engineering at the time, I always had my hands on the final mix. In those days, the mastering was sitting next to this engineer with a big machine that cut a groove in a great big piece of vinyl, which was quite nice. What was nice was you could sign it, autograph the actual final master so everything that got printed from that had your autograph on it. That was nice.

How has it been to revisit Incantations 35 years on? Do you still feel the way you felt about it when you first recorded it?

MO: I think there’s a lot of good ideas there. It was a transitional album between two different phases of my career and my life, really. It was in 1978, so I was still only 25 and I had hardly really gotten to adulthood. During that album, I kind of went through a metamorphosis. I became much more outgoing and started doing live concerts and traveling a lot and recording with other musicians and session men. The first step on that new journey was a track called ‘Guilty’ which is quite different from the rest of the Incantations album.

With those early records in general, there’s a very forward-thinking approach to electronics, but that was obviously quite early to be using some of that stuff. What kind of gear were you using back then?

MO: Well, synthesizers were brand new. There were only two that were usable, and they were completely monotonic, so you could only play one note. Well, actually, there was a string synthesizer called a Solina that you could play chords with, and it sounded kind of like a string machine, and then there was something by Roland that made a kind of clarinet sound, and that was monotonic. There were other synths before that, but they were very primitive kind of things.

Was it difficult or expensive to get your hands on that kind of stuff back in the early ’70s?

MO: Music stores would carry them, but the main keyboards were things like proper pianos and organs. Different kinds of organs like a Hammond or a Lowrey or a Hoffrichter or the Vox Continental. People were still using that. It was just the beginning of synthesizers, so there isn’t very much synthesizer on Incantations apart from little sections. There’s a lot of live musicians. Live strings, a lot of live orchestral percussion. I used to play most of the orchestral percussion myself, but I had some help by a couple of French percussionists Pierre and his brother Benoit Moerlen, who were wonderful vibraphone and xylophone players, and Pierre was a drummer as well.

Your music’s always been very successful in evoking emotion, but when you look back to the Tubular Bells days, obviously William Friedkin when he chose it for The Exorcist but also contemporarily a lot of extreme metal bands have cited that as one of the most frightening pieces of music. Was that going through your mind when you were writing it, or do you hope that your music can evoke fear?

MO: It’s funny, I still hear it every day. It’s such a cliché now. It’s like every time there’s something scary in the sea, you hear the Jaws piano, that dum-dum-dum-dum. Anytime there’s something a little bit spooky, Outer Limits type of thing, you hear that tinkly piano, they just change the notes around a little bit. It wasn’t made that way, although I was pretty paranoid at the time. I was only 19 and I had a lot of psychological problems and phobias. But I didn’t design it as a piece of scary movie music, of course not.

Have you kind of come to terms with it being your iconic piece? When people think Mike Oldfield, they tend to think if not Tubular Bells, then The Exorcist soundtrack.

MO: It doesn’t bother me. It’s quite amusing, every Halloween I switch on CNN and I hear Tubular Bells. I’m quite lucky because eventually as performance royalties come in, the payment after Halloween is always quite comfortable, and having that for something I designed 40 years ago in a little tiny room in a horrible part of London is quite nice.

In the ’70s you tended to kind of be lumped into the English prog rock movement, but unlike most of your presumed contemporaries you’re still prolific and relevant and making all these great, interesting records. What gives you that drive to kill the temptation to be complacent?

MO: Well, I’m not afraid to try new ideas. Tubular Bells was that, a lot of new ideas. In about 2005 I just had the idea to make a piece of totally orchestral music, and I’ve always been lucky in terms of having good people in my record company. I signed with Universal, and then they put me onto the classical department, Universal Classics and Jazz, and they organized for me to have Karl Jenkins as the conductor/arranger for that, and he’s a master. So that was lucky, and that album (ed. – Music of the Spheres) did very well. And that was three or four years ago.

I’ve explored all different types of music. I was much more purist when I was younger, like in the Incantations days, and that was good in a way, but I think if I hadn’t been prepared to expand and try new avenues, the first being the disco track ‘Guilty,’ and since then I’ve tried lots and lots of other things, and I’m still trying other things. It’s the age-old philosophy of "Embrace change", I suppose. That is the secret.