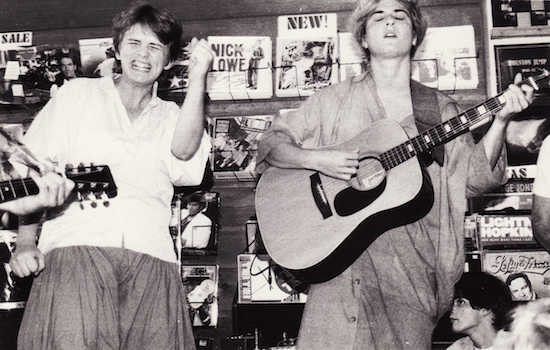

Mellissa Cobb and Gretchen Phillips of Meat Joy

In the early 1980s, Austin, Texas band Meat Joy established an internal rule so smart, it’s a wonder that it’s not universal. Whenever a member suggested a musical idea, it had to be pursued at least once – no immediate negative reactions, no out-of-hand dismissals. Maybe this is why Meat Joy’s sound was so diverse and unpredictable. On the band’s self-titled 1984 debut album – now reissued on their own label – raging rock tunes sit snugly next to improvised jams, lo-fi folk, plaintive semi-ballads, and spliced-in audio interludes.

Meat Joy’s try-everything approach wasn’t just productive, it was efficient, too. “It made things go faster,” says band member Mellissa Cobb. “If an idea wasn’t going to work, we would know right away.” The results on Meat Joy never sound over-thought or overworked, though the band could be quite precise in its twists and turns. But all their songs have an exciting immediacy, without a lot of distance between thought and actualisation.

The band itself came together with similar speed, when Cobb, Gretchen Phillips, and Teresa Taylor started jamming together in the summer of 1982. Tim Mateer befriended Cobb after seeing her band Stick Figures and soon joined in on the jams, as did mutual friend John Perkins. When Taylor left to join Butthole Surfers, Jamie Spidle took her place, and after a few shows, the quintet adopted the name Meat Joy from Carolee Schneemann’s 1964 work of “kinetic theater.”

Some had played in bands before, while others had barely touched instruments. “When I played bass, I put my fingers where they told me to, and tried to remember the pattern,” explains Mateer. “I would put color-coded tape next to the keys on the keyboard to know which ones to play.” Meat Joy saw this imbalance in experience as a creative spark, making learning a vital part of the music, such as when they ended sets with improvisations. Yet most of their shows were planned out in advance. As Mateer recalls, “We would practice exactly the way we meant to play our next gig, with the songs in order.”

This combination of openness and preparedness was a good fit for the Austin scene, where bands like Glass Eye and Technicolor Yawns experimented in front of audiences seeking new sounds. Not everyone got it, of course, but that wasn’t necessarily what Meat Joy wanted anyway. “At one show in Dallas, someone asked if we were a ‘lesbian Christian band,’” says Perkins, laughing. “From then on we’d say that we were ‘not just another lesbian Christian band.’”

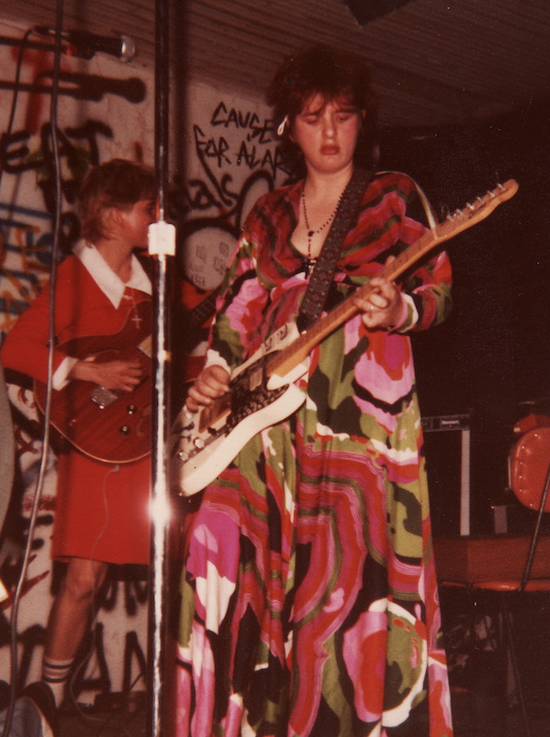

Still, issues of sexuality and politics were serious stuff for Meat Joy. They saw LGBTQ pioneers in the Texas punk scene – specifically Gary Floyd of the Dicks and Randy “Biscuit” Turner of the Big Boys – as mentors. For Phillips, who is gay, her bandmates’ willingness to take her seriously made Meat Joy her “first adult love”. She says: “We were looking at sexual politics, the push-me-pull-you between men and women, women and women, and everyone was open to the songs being about that… Before there was any rhetoric about straight allies, this was just them being buddies and being interested. I don’t remember long philosophical conversations, but I remember profound comfort and safety, a feeling of being understood.” Of course, the punk scene around them wasn’t immune to problems; Perkins notes that he wrote the ripping jam ‘Proud To Be Stupid’ to point out how underground bands could be as insensitive as anyone else in 80s American culture.

Mellissa Cobb

That and the other songs on Meat Joy were recorded at Austin studio ESR, where the group had initially recorded a song for a compilation. Their repertoire wasn’t long enough to fill an LP, so each member got to contribute some audio of their own. For instance, opener ‘Prelude In C-Flat’ was recorded during a show in Spidle’s house, which doubled as the Meat Joy practice space. The various additions help form a surreal audio narrative stretched across two continuous vinyl sides.

The band’s own narrative ended about a year after Meat Joy came out. A combination of factors, including members’ other creative pursuits, led to what Cobb admits were “some hard feelings, [and] it was very sad.” Before taking the stage at Austin’s Continental Club in April of 1985, Perkins wondered aloud if this should be their last show. “No one objected,” he remembers. “So we announced we were done during the set. Some people thought we were joking, but we weren’t.”

Tim Mateer

The members of Meat Joy went on to other creative pursuits, keeping in touch sporadically. A few years ago, talk of playing again circulated, in part because of Perkins’ realisation that Meat Joy was “the most freeing creative experience I have ever been a part of.” (That’s a pretty remarkable sentiment considering he’s had a successful acting career under the name John Hawkes). During the pandemic, they started a weekly FaceTime session that they maintain to this day. Along with the Meat Joy reissue, a live tape and a book detailing their history are out now, and the band have recently played three shows in Austin.

Everyone in Meat Joy radiates joy at this development, gushing about their love for each other and what they do together. “It feels the same as it did then,” says Mateer. “Except we’re all smarter now.” They fear jinxing things by over-defining what’s next – as Phillips puts it, “We don’t want God to hear our plans and start laughing” – but it’s safe to say Meat Joy are happy to share creative space once again.

The reissue of Meat Joy, live tape and a book charting the band’s history are available here