In early September, Matthew Herbert brought his One Pig album to life at London’s Royal Opera House. As his group used a wire enclosure that resembled a pen for livestock to trigger rhythms and melodies, a chef appeared at the back of the stage and began to cook a selection of pork dishes. A fan behind her filled the room with the aroma of cooking. "Two of my friends were sat next to each other," Herbert says. "One found it totally disgusting and didn’t want to eat pork for a while; the other one was like, ‘Get me to a restaurant.’ And both of them are meat-eaters."

Recorded over the lifetime of one animal from birth (rustling straw and grunts), through life (the sounds of a farm and the English weather) and eventual eating (the album ends with the sound of cutlery on crockery), One Pig is a thoughtful meditation on what Herbert describes as "the drama and the melancholy of nurturing animals to slaughter them to eat."

Herbert himself is a meat-eater. "My intention was to understand the consequences of that decision and to witness the whole process, and in doing so I wanted to amplify that quite explicit but often entirely invisible friction that’s constantly surrounding us between things that we do and the consequences of our actions," he says. "It’s a very important part of my work generally — pushing my microphone into these darkened holes."

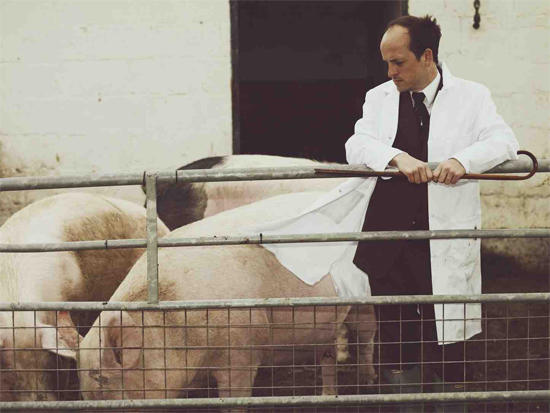

On One Pig, this "darkened hole" is our relationship with farming and the meat industry, using a pig as the focus. As Herbert explains: "One of the main stories with pigs is how badly we treat them. Eighty-to-ninety per cent of the pork that you’re likely to eat is produced in pretty hideous conditions." But he was unable to gain access to one of the more industrialised farms. "The Government has handed control of our food supply to supermarkets, so it’s just bound by traditional corporate secrecy. I thought that if I can’t get there I should follow a pig from a farmer whose meat I have eaten in the past."

Herbert — an electronic artist who has previously collaborated with Björk, written two big-band albums and produced earlier works also constructed from field recordings — found a farm local to his home in rural Suffolk to which he made regular trips during the life of the pig. While your supermarket banger might not be 100 per cent pork, this album is entirely constructed from Herbert’s recordings. "I’m very pedantic and purist when it comes to what I use and what I don’t use, because for me if you just start using sounds from elsewhere it would start to undermine the integrity of the record and the process," he says. "You have to submit to the sounds that you have, and that ends up telling the stories on your behalf."

Herbert adds that the hardest part of what he does is finding melody in the masses of recordings: "We rely on harmony — those shifts in frequency and tonality to provide the emotional heart. It’s pretty hard to get nuances of emotion simply through rhythm and percussion." Hence a cow mooing became the source of a rich melody in the ‘October’ section of the album, and that had the happy coincidence of broadening out One Pig. "It was supposed to be focused on the pig, but when you hear the cow you think ‘Well, that’s been eaten now,’ and there are ducks there that were eaten at Christmas. It says ‘Matthew Herbert, One Pig‘ but in many ways it should be ‘Matthew Herbert plus Farmyard Friends’. The record was made by them as much as it is made by me."

He adds that the seasons, which the majority of us who live in cities barely experience to any real extent, also made themselves felt throughout One Pig. "The seasons helped tell the story, he explains. "It started off very calmly and beautifully, in the summer, in the stable with hay and the sun was out, it was quite wonderful. In November it’s incredibly windy, on top of this hill, and it creates a real drama. Because of where it is on the record it starts to unsettle you, that things aren’t right or something’s changing. Come December you hear my footsteps crunching through the ice and the snow, and it’s very metallic. The whole thing is very brutal. That seasonal impact is a real parallel narrative with the record that I was really surprised about."

Herbert says there’s nothing queasily elegiac about One Pig, which he feels reflects the nature of farming in general. The record is more industrial than pastoral, with the sounds of clanging pens, and things that are not for the squeamish. "One of the things that we do at butchery is beat the air out of the lungs, and that’s one of the noises that you hear on the album. In the context of a record like this, when you’ve heard a pig take its first breath, to then hear a few months later the air being beaten out of its lungs is quite shocking."

This honest approach meant Herbert avoided a Babe-esque romantic engagement with the pig. "I didn’t become that emotionally attached to the pig, because ultimately the pig really didn’t give a shit about me," he continues. "I went back to the sty where the pig was raised and there were some other pigs there. You hear me finish singing and almost the next thing you hear is a pig taking a piss, loudly, as if to say, ‘Well, that’s what I think of you and your record.’"

And how has One Pig impacted Herbert’s relationship with pork? "I think it’s impossible not to consume pork — it’s injected into chicken breasts, it’s in jellies, sweets and trifles, wine and beer and milk and bread." But when it comes down to the pork scratching, black pudding or smoked rashers, the One Pig experience has had a profound effect: "I think there’s something really empowering about removing something from your diet. It felt like a logical extension of what I was doing. Since I finished the record I haven’t eaten pork."