Photograph courtesy of Jon Stanley Austin

If you’re reading this website, the chances are that the sounds created by the technologies of Dr. Robert Moog have had a considerable bearing in your musical upbringing. Originally seen as a sonic bauble for ’60s psychedelicists looking to freak out their compositions, one could argue that these powerful banks of oscillators, filters and modulators only really came into their own with the advent of Tangerine Dream’s cosmic sublime, Kraftwerk’s human-droid hybrid and Giorgio Moroder’s machine funk – in short, the genesis of popular electronic music as we know it.

All this makes Matthew Bourne’s relationship to the machine entirely more personal. A virtuosic jazz pianist, improviser and composer, Bourne came to synthesisers via the cryptic mutant jazz of Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi-period work. Thus, while albums such as 2012’s Montauk Variations have showcased his skill in grafting a classical harmonic sensibility on to jazz virtuosity via the medium of the solo acoustic piano, he’s also been keen to explore his love of analogue synths. Last year’s Radioland: Radio-Activity Revisited saw him pay tribute to the seminal Kraftwerk album in collaboration with the French experimentalist Franck Vigroux, expanding widely on the material in live improvisations.

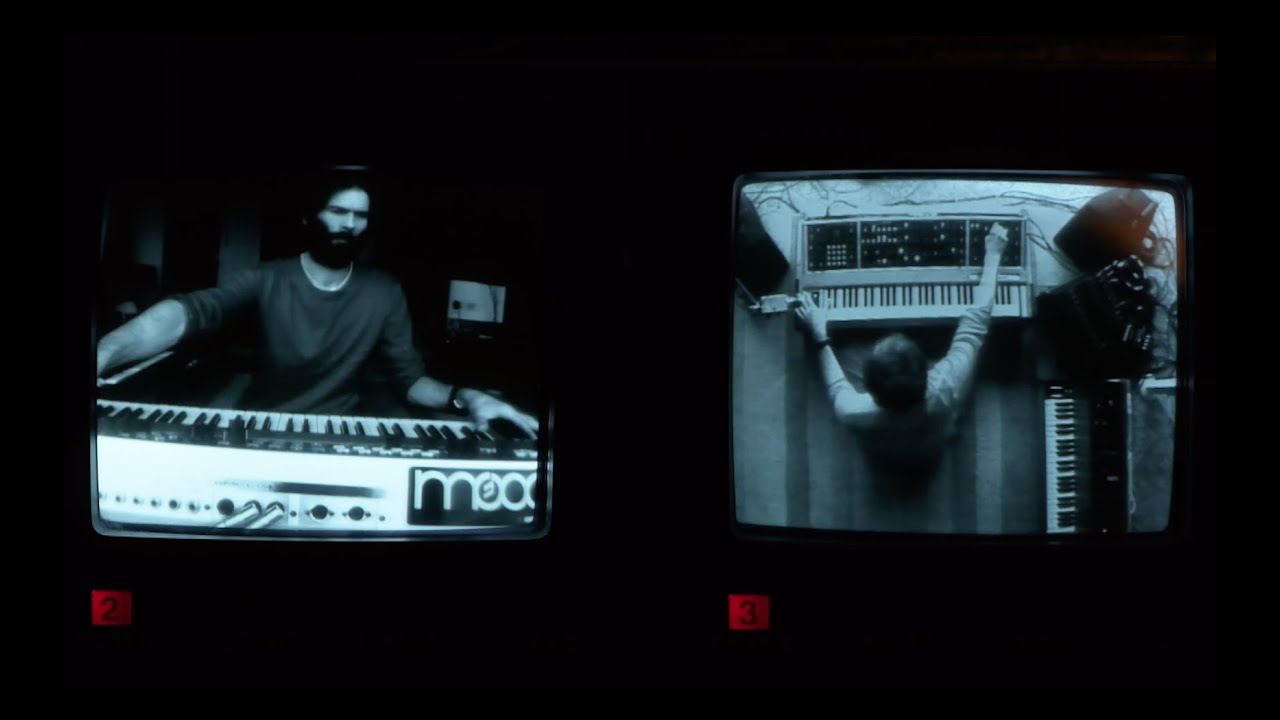

Now Bourne seeks to further this electronic project with moogmemory, an album dedicated to and made entirely using the Memorymoog, the last official synthesiser made by Moog before the company went bankrupt. While it has been used as an instrument for post-rave fodder by the likes of The Orb, Air and 808 State in the past, in Bourne’s hands the sheer power and physicality of the instrument shines through. From the contemplative, sparse structures of ‘Alex’ to the noise-saturated, pumping tones of ‘Horn & Vellum’ via the spaciously eerie ‘I Loved Her, Madly’, it’s a testament to the Memorymoog’s versatility and creative potential. Recently Bourne has taken the project on the road, with visual accompaniment from Michael England who feeds the album’s personal and geographical references through an LZX video synth. As Bourne says of the live experience: "Visually, it’s a complex and multilayered piece of work. Just as well, really, as watching someone play keyboard synthesisers on its own is a pretty fucking dull experience." Ears pricked by those singing analogue patches, tQ caught up with Bourne to discuss the project and his relationship with electronic music.

There’s a really wide range of tones and timbres on the album. What came first, the melodies or the patches?

Matthew Bourne: Well, the melodies are the patches and vice versa. Most of the patches generate multi-timbral, rhythmic and melodic elements all at once. All of those elements in ‘Daniziel’, for example, are generated from a single patch. There is some multi-tracking – as is there on ‘Horn & Vellum’, ‘Nils’ and ‘Andrew’ – after the middle section, but only to reinforce the bass and melodic elements already being generated. In this sense, I’m just the guy who depresses a bunch of keys and listens to what she has to say and feels for when to hit the record button. The synthesiser is the creator here and does all of the work.

Do you find that different pieces of technological equipment stimulate different types of creativity?

MB: Definitely – I’m certainly a keyboard player, first and foremost, so when I first began to become interested in analogue synthesisers, it was through the individual instruments themselves: each one had/has their own default character and function and operational quirks. Modular synthesisers are completely different, though. Synthesising sound from scratch – that’s the real thing, as far as I’m concerned, and am in awe of those who are avid practitioners of such.

Musicians often talk about how Moogs can be quite unpredictable. Do you feel like there’s an aleatoric element with this synthesiser that you wanted to harness?

MB: This is true, although, all analogue synthesisers of a certain vintage are susceptible to problems of varying sorts. The big polyphonic synthesisers: the Memorymoog, Polymoog, Prophet-5, et al.; none of them are immune – the same goes for more modern and digital counterparts. Nothing is 100 per cent reliable.

With regard to the instrument on the album, though, it is important to emphasise that it is not a standard Memorymoog, but a heavily-modified Lintronics Advanced Memorymoog (LAMM), as modified by an electronic engineer, Rudi Linhard at Lintronics in Germany. Without going into too much detail about the modification procedure itself, let’s just say that the LAMM is as reliable as any synthesiser being made today, and then some. Sure, it has its quirks, but these are not invasive or disruptive in any way. It’s an incredible instrument, and is testimony to Rudi’s incredible engineering skill and dedication to refining what was a very troublesome instrument in its original incarnation.

I believe there was no use of computers or sequencers on moogmemory. Was it important for you to make this an all-analogue project?

MB: Yes, that’s right. I just wanted the instrument to speak for itself, without additions or ‘help’ from MIDI controls, or anything else. Of course there is an on-board arpeggiator, which accounts for all of the rhythmic elements in certain tracks. It wasn’t a conscious decision to avoid computer sequencing or MIDI, it just occurred to me that the LAMM should have its own platform, in the absence of other instruments or technology. I like limitations.

Also, as I could find very little evidence to indicate that this instrument had been given a fair showcase in its own right, I decided to make this the raison d’être for the recording process. That said, I still feel as if I am only scratching the surface of the instrument’s potential. It took Phil James the best part of 25 years to become fluent in its operation. Watching him scroll through its functions – even now – puts my own operational knowledge of it to shame!

There’s definitely a filmic, soundtrack-esque quality to some of the tracks on the album, particularly ‘On Rivock Edge’. Did you have visuals or landscapes in mind when you were composing the pieces?

MB: Many people draw such associations with some of the music and particularly with ‘On Rivock Edge’. The short answer is no, I didn’t consciously visualise anything whilst making any of my work. The associations usually come afterwards, whilst listening back to the music. But this is merely an enforced suggestion on my part. The music neither means nor implies anything, really. I do, however, attempt to ‘place’ the music: regarding the titles, I prefer to give the music to people as gifts, or assign it to places that mean something to me. So in the example of ‘On Rivock Edge’, this is an area of bleak moorland lying directly above where I live. It’s a short walk away and a place where I go running. It’s a silent, eerie, beautiful place. One is lucky to see or hear anything other than curlew (at this time of year) or grouse. The title is also a play on Ralph Vaughan Williams’ composition, On Wenlock Edge – a very different work and place, altogether! The other pieces are titled after friends or lost loves. I have an unhealthy penchant for wallowing in nostalgia.

Can you tell me a little about the live tour you’ve been doing with Michael England on the LZX video synth? Are you aiming to visually embellish the material on the album or are you aiming for something different?

MB: Michael England is the driving force behind the album’s title, visual conception, in bringing together a sense of place and the very human story behind this particular instrument. He has also added massive conceptual depth to the project as a whole. For example, Michael went all the way to Montauk, New York, just to shoot impressions of a place I’d visited years earlier, which resulted in Montauk Variations. That marked a turning point for me, personally and musically. The idea was to tie in a place that had marked the start of a new musical journey with footage from my current environment on the moors in Airedale, and other parts of Yorkshire and the Pennines, where the music was made. So there is a very strong cinematic element to the live work with a very long and beautiful film sequence that accompanies ‘I Loved Her, Madly’, as the centrepiece of the live show.

You were also heavily involved with Radioland, a tribute to Kraftwerk. Having started in jazz, is this a complete turn to the world of electronics for you?

MB: No, not really. I’d been introduced to synthesisers and electronic music by Graham Hearn at Leeds College of Music. I was also listening to a lot of Herbie Hancock’s work – particularly the albums made under the banner of Mwandishi, arguably one of the most underrated, under-discussed bands of that period. I met Franck Vigroux in 2006, whose knowledge and skill in electronics I admire immensely. We did an album together in 2007 [Me Madame (good News from Wonderland)], and have worked together ever since. Radioland was Franck’s suggestion, and was in response to us doing something together again, and that wasn’t us simply meeting up and improvising again. We wanted something more challenging and musically relevant to us that we could work towards.

Do you notice any marked differences between composing for piano and composing for synths? Does your approach to the instrument differ in anyway?

MB: As long as things don’t become too contrived, or I become too conscious of design, all is well. The particular challenge of working with this particular synthesiser lies in first finding a sound that provokes initial musical exploration. It’s at this point that I tried to capture things, without allowing ‘grand design’ and procrastination to overtake impulsivity and spontaneity. In this sense, once I’d captured something that was good enough, I would move on. Subsequent repetition and refining of initial ideas is a false and dangerous trail, for me, at least.

moogmemory is out now on Leaf. Matthew Bourne plays Outskirts festival at Platform Glasgow on April 23; for full details and tickets, head here