Photograph courtesy of Jason Fulford

Saxophonist, composer, improviser, visual artist: Matana Roberts is one of the most exciting artists working today, and nowhere better demonstrating this is her COIN COIN project, a 12-chapter work exploring African-American history. Montreal-based Constellation Records have so far released three chapters of the project, named after Marie Thérèse "Coincoin" Metoyer, the freed slave and businesswoman who helped establish the Creole community in Cane River, Louisiana, with each radically different in sound. COIN COIN Chapter One: Gens de couleur libres from 2011 is a large ensemble electro-acoustic free jazz piece, incorporating gospel and blues elements, as well as Roberts’ harrowing primal screams. Chapter Two: Mississippi Moonchile, released in 2013, is arranged for an acoustic jazz quartet and operatic tenor, while this year’s Chapter Three: river run thee is Roberts’ homage to noise, a collage of electronics, voices and saxophone. Each chapter is composed using a method she calls "panoramic sound quilting", whereby she creates collage-based visual scores for improvising musicians. She also has a number of albums outside the project, including The Chicago Project from 2008, 2011’s Live In London and the excellent solo alto saxophone set always., released earlier this year.

Roberts came up through the 1990s Chicago jazz and punk scenes. She was given her first gig by the late, great Fred Anderson, saxophonist and proprietor of the city’s legendary Velvet Lounge venue. Sticks And Stones, her trio with bassist Joshua Abrams and drummer Chad Taylor became the venue’s house band and went on to record two albums, a self-titled LP from 2002 and Shed Grace in 2004. After leaving Chicago, Roberts became an associate member of the famous arts collective the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), meeting great musicians such as flautist Nicole Mitchell and percussionist Don Moye. She also worked with musicians from the city’s post-rock scene, including members of Tortoise, and her punk and indie connections have seen her playing with TV On The Radio, Godspeed You! Black Emperor and Thee Silver Mt. Zion Memorial Orchestra. Through the latter bands, she became involved in the Montreal music and arts scene, signing to Constellation and recording at their Hotel2Tango studio.

Before she brings her Chapter Three shows to Europe, beginning with a gig in London tonight, we talked to her about using visual ephemera to score her music, exploring history through place and why she’d prefer to be called a craftsperson than an artist.

What would you say is the main aim of the COIN COIN project?

MR: I have a really big interest in the spirit world: spooks and the things we can’t necessarily see but feel. An exploration of ghosts and things of that nature. There was a period of my childhood where I tried to contact people on that plane and I stopped doing that as a teenager because I heard it can induce states of psychosis if you don’t have a proper guide. So I left that and I realised that music is my medium, my guide. So the COIN COIN work has a lot to do with stories and people from my ancestral history in the sense that I’ve always wanted to have some kind of contact with [them]. Also I’m a history geek and I love American history. It’s so bizarre and so problematic and I love the many conundrums that it represents. You can go down so many black holes and this project has got me in a certain hole as well! It’s a way of interpreting that history in a way that makes sense to me.

Each chapter you’ve released so far has a very different sound, but there are certain threads running through them all: the singing, the speaking, the voices from past and present intermingling. How do you decide what the musical setting will be for each chapter?

MR: There are 12 chapters: two solo chapters and ten ensemble chapters. Originally it was ten ensemble chapters and then I realised that I really also love exploring solo playing in different formats. I had about ten stories from my own family history that I wanted to explore to see if they were actually true, because you know how family stories get passed down and by the time it gets to you it’s a different story. But I noticed that stories I had really linked up with these particular areas of American history I’d always been fascinated by, so it was a way for me to focus that, learn it. I love learning.

But I also like working with different ways I can collage electronically and I really like working with image and video, so I decided to focus this one chapter around my interests in mixing those mediums.

You mention video. Is that something you use as part of your live performances?

MR: Yeah, I’m trying to figure out a way to turn the video work I do into actual interactive video scores. I love working with my hands. The computer has taken over my life in a way that makes me really uncomfortable. I’m trying to find a happy medium that gives me freedom but also still goes back to the idea of craft. A lot of my video work is super lo-fi on purpose. I’m not trying to become technically super proficient. The only thing I’m interested in becoming technically proficient on is my alto saxophone. And the collage aesthetic that I’m really interested in, I’m trying to be really careful about how I use visual tools and that’s why Chapter Three is basically an overdubs record, because I could’ve recreated a lot of that with fancy toys, but I didn’t want to do that.

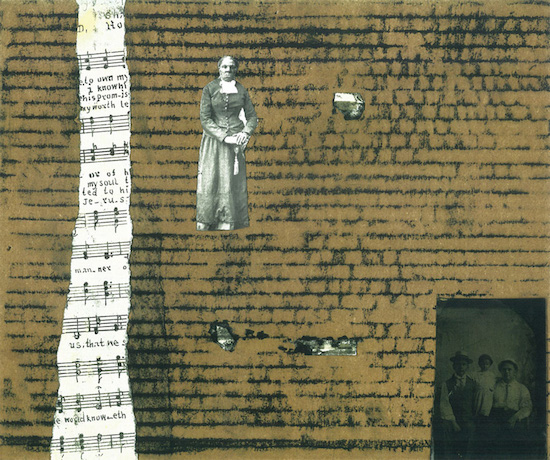

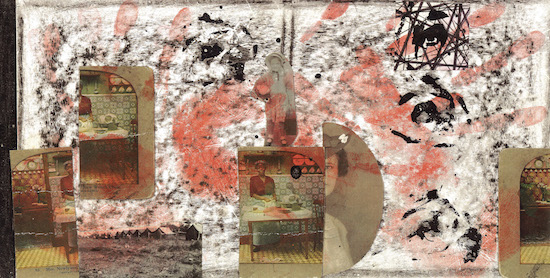

I’m really interested in how your scores work. Parts of them are reproduced in the album sleeves and they’re really fascinating: these collages of notation, writing, old photographs…

MR: I’m really interested in ephemera. Again it’s about these traces of people, traces of stories, these things that we leave behind that seem to maybe not have any meaning, but to someone [they mean something]. I spend a lot of my free time in old junk shops just digging through stuff like that and I inherited a great deal of family ephemera which gives me an incredible amount of joy. It’s just about the only thing of value that I own outside of my saxophone. I also love reading music and I love dealing with Western notation, so the full scores are a combination of the visual material and Western notation, and I collage them together in a way that makes sense to me and then I experiment with it on different musicians who I feel can handle it.

So for example, if you have a particular photograph, does that act as a visual cue for a predetermined part or a certain approach to improvisation?

MR: To be quite honest it really depends on the particular score and the particular moment. I do liberally use Butch Morris’ system of conducting improvisers [Conduction], something that I learned a lot about from playing in Burnt Sugar, a really interesting New York band, for three or four years. Butch says he got his system from watching Sun Ra. It’s this interesting passed-down sort of thing. So it’s a combination of visual cues and, depending on the mood and the music I’m trying to set, there will be certain things in the photographs or the collage that might be cues, or might be actual notes, or – you can look in a photograph and see a certain story. If you’re really paying attention there are things that you can actually see and I try to focus on that. A lot of the ephemera I collect, there’s a lot of subtext in the ephemera. Sometimes I take actual data from the ephemera and turn it into sound because it’s very easy to turn numbers or letters or just syllables. For instance, just talking to you, I could turn this whole sentence into a rhythm. I could turn this whole sentence, depending on the pitches that I’m speaking [uses sing-speak voice from COIN COIN, stressing every second syllable]: "I could turn this sentence into a sound." So I move in that direction. It seems to be the only way I know how to understand music and art and the placement of things – I’m fascinated with the placement of things.

One of the things I find interesting with COIN COIN is that you’re using quite a sing-song voice to relate some very harrowing material about slavery, violence, abuse. Then there’s the recurring phrase in Chapter Two: "There are some things I just can’t tell you about, honey", which is something your grandmother would say when talking about her past. You’ve said she would laugh after saying that. In both cases, do you see the humour and playfulness as a way of dealing with trauma, transforming the experience?

MR: Yeah – when you read enough stories about people who have been through different levels of trauma, and it doesn’t matter what the history is, trauma is trauma, there’s always this freeing of the spirit. Someone can do anything they want to you on the outside, but whatever they do to me they cannot destroy what’s on my inside. Mentally that cannot be taken away from me, no matter what someone does. And even if someone does something that takes away from me mentally, like they smash my head, the negativity of that action is still on them, it’s not on me. I just learned through my own personal history and the history of my family history, how much they used laughter and humour to put that over there somewhere – that compartmentalising of things to deal with the trauma.

So my grandmother on that second chapter, what was so amazing about that was the amount of times she said, "There are some things I just can’t tell you about, honey." She said it so many times, and I was raised to never question an elder like that – there was no way I was going to push her about what she meant. But the fact that she would laugh – and she had a very difficult life, her life was easy in no sense of the word – she just passed it somewhere. And there are memories that will die with her; they were not meant for me, they were meant for her. But I feel a great amount of strength in knowing that through whatever those moments were, she still stood and was kind enough to share with me these beautiful things, and that’s what you have to do. I saw my mother go through the same thing when she was dying of cancer, it’s like the silver lining. My mother said there’s a silver lining and I think that’s a learned behaviour that gets passed down through the ages.

It’s also a form of defiance?

MR: Yeah, definitely a defiance and resistance. You have to deal with the cards you’ve been dealt and do the best that you can. Life is so short that, 100 years from today, how much will certain things matter? There’s some parts of that I really take to heart and there’s some that I don’t, because I still think history is important: it’s important to interrogate history, it’s important to document history, because as a society we need constant reminders of the things that we’ve done in the past in the hope we can stop repeating these horrible lessons.

InChapter Three you used field recordings from your travels in Mississippi. Was that trip about tracing your family history, or just getting a feel for the place?

MR: Well, I went through the South, just to be in the South. I didn’t really do as much ancestral history as maybe I should have, but I’d never spent a lot of time in the South. As far south as I had been for longer periods of time was North Carolina, I have some family there. But as far as the Deep South – I had relatives who said, "We’re never going back there ever again in this life." And they would tell me these horrific stories, but yet I still felt a connection to a certain cultural… something that’s just very different to New York, it’s just a different vibration, a very different idea of kindness, a very different idea of code, and I really wanted to know what it felt like to be in it. So I travelled through Tennessee, Mississippi and Louisiana by myself and I’ll be back there again in February. I’ll be going back there pretty much yearly, because this history that I’m dealing with, American history really sits in the belly of these states. It’s not in New York, it’s not in Washington DC. Texas, Louisiana, Georgia, Florida even, it’s in these Southern places and these port cities. I have such a rich ancestral history in those three states [Tennessee, Mississippi and Louisiana] I just want to walk around, encase myself in it.

Is place important to you as a way of exploring history and memory?

MR: It’s really interesting. I live on a houseboat in a part of Brooklyn where there are 360 species of birds and every day I’m woken up by what’s called a laughing gull and it makes a sound like I’ve never heard in my life. If I’m on the phone and she starts singing, people are like, "Where are you?" I’m in Brooklyn! It’s the same as being in the South. I did field recordings of bell sounds, there are so many bells, and the only time I’ve heard so many bells is when I’m running through little towns in Europe. I don’t hear that in NY in the same way. Listening to the birds tells you different things about a place. [In the South] I heard bird sounds I’d never heard before. I heard street sounds and country sounds and city sounds that are very different from what it is I’m used to and I get very fascinated about how that marks a place. It made me think about how painful it must have been for a lot of my family to leave the South, because it’s so beautiful there. New York is beautiful, but [the South] makes it look like a wasteland.

You call your collage approach "panoramic sound quilting". Weaving, quilting: does that tie in with your comments that craft is what you do, as opposed to art?

MR: Yeah, I’m really fascinated with folk arts that had a utilitarian focus. I just played a show in Canada two days ago in a church that was used during the Underground Railroad and on the walls were message quilts, quilts that were passed around slaves that showed routes that slave masters were not able to interpret – there was this whole code. I just love folk art traditions, American or not. The artistry was part of the craft, but the focus wasn’t on artistry, it was focussed on use and generally focussed on community use. I get excited about the possibilities of that. It’s nice that people can call me an artist and it’s nice that I can refer to myself as such, but it also kind of separates me from the common man in a way that I don’t wish to be, so craftsperson makes me feel a bit more connected.

Is your use of voices and testimonies another aspect of being connected?

MR: Yeah. COIN COIN Chapter Three was supposed to be my ode to noise music, I love noise. There were no lyrics and no words on that record. And then I listened to it and it was like, ugh, instead of bringing people in, it might shut people down and I’m not trying to do that, so how do I bring people in? Well, words, narrative and voice. I really, really don’t like to sing, but I love making people sing. I love group singing, sacred harp singing, choral singing, recordings of people singing sea shanties, work songs, prison songs – how people just sang to get through things. So I try to put that in all the records and I always try to have some kind of group. I like the spontaneity. Something seems to happen when people sing together; it completely changes the energy of any space. The saxophone was created to mimic the human voice and I think that’s why I gravitated toward the saxophone eventually. I’d loved the clarinet, but there’s something about the saxophone that just grabs you.

The albums also have these folk tunes, gospel songs and public domain songs by people like Stephen Foster running through them. I guess that’s another aspect of being connected, using the people’s songs?

MR: Yeah. ‘In The Garden’ was not my choice. It was a song requested by my mom at her funeral service and she died ten days before Chapter One was recorded. Since Chapter Two was so much about the church, I just felt – I performed Chapter Two two days before her funeral and I just tacked it on there in this one performance, because I felt guilty I was performing but I knew she’d be happy that I was going through with it and I just wanted to be with her. It sounded so good we just left it on there.

Obviously COIN COIN is a huge undertaking, but what other projects do you have on the go?

MR: I’m always doing lots of different things. My dream is to do really large public sound-works. Leading a band is fun, but it’s not always something I want to continually focus on. I have my toes in a lot of different things. I just did this week of performance art at the Whitney Museum and I’ll be continuing with that towards the end of the year. I always have other little things going on because the COIN COIN work can become a little too all-encompassing. If I treat it too precious I’m afraid I might not get through it, so I have to have other places to put my thought processes.

There definitely is more COIN COIN to come. I’m kind of distracted with finishing this residency at the Whitney. They’ve been so good to me – it’s amazing. I’ve got a few pieces in an exhibition at Chicago just now that’s about to travel to Philly, so I’m making more visual art. The Whitney, they’re allowing me to build these 15-foot scores, so I’m trying to deal with that. I’ve been commissioned this year to write a video opera, trying to figure out a way to deal with that.

Is the score on video, or is it performed on video?

MR: It’s going to be performed. It’s focussed around the theme of the police brutality that’s been going on. I need to exorcise some of that out of my system. I can’t let it sit on my psyche the way it has. I’ll be doing that and some other little collaborations as the year ends and then I’ll be travelling in the South. I just moved over to a new boat. My new boat is not winterised so I’m gonna take off for a portion of the winter and come back and deal with it in the spring.

always. is out now on Relative Pitch Records and the COIN COIN albums are available from Constellation. Matana Roberts plays Oslo in London tonight and the Prince Albert in Brighton tomorrow, October 7, before touring Europe, taking in a set at OUT.FEST in Barreiro, Portugal on October 8; head here for full details and tickets. OUT.FEST runs from October 8-11; for full details, head to their website