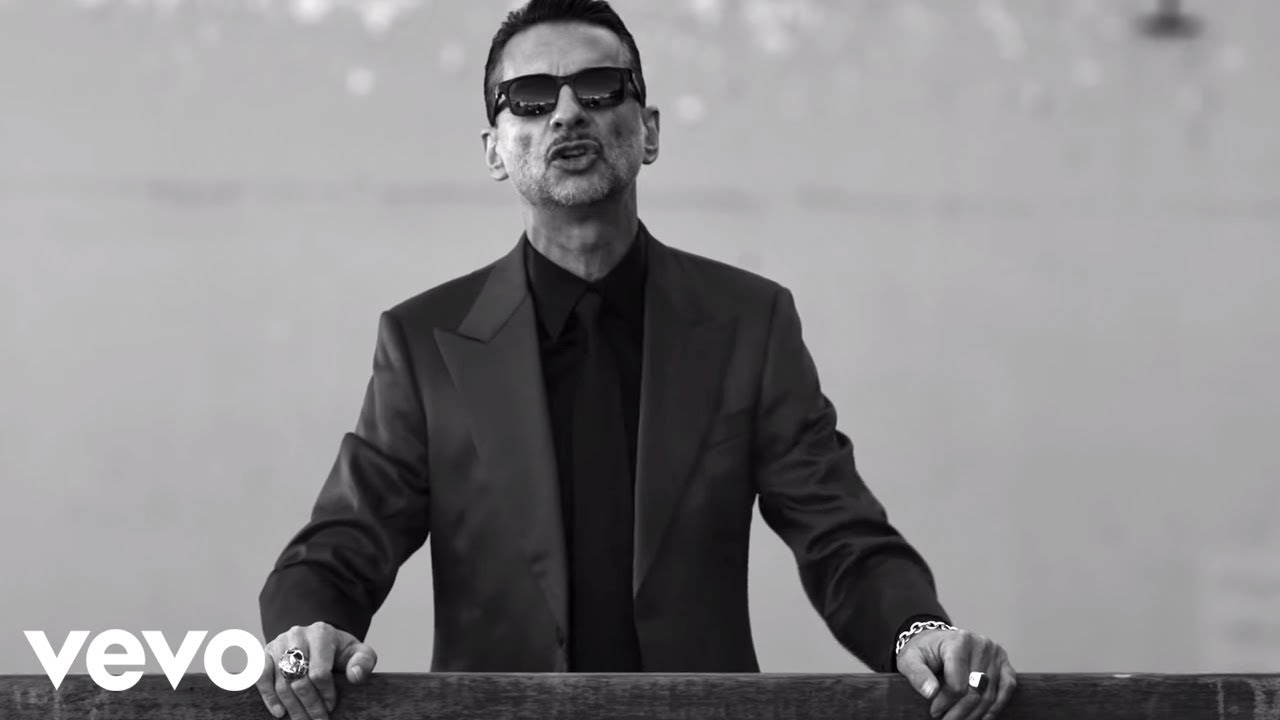

Portrait by Anton Corbijn

If there’s one thing Depeche Mode isn’t it’s favourite sons. A few years ago I went on a bus and walking tour of the band’s hometown, Essex’s (no longer) New Town of Basildon. In our party were Germans, Scandinavians, east Europeans – but if memory serves, no British people, and certainly no one from Essex. As we crept around the former garage of Vince Clarke, where the band rehearsed in their early days, a neighbour pulled up and smilingly explained she’d never heard of Depeche Mode. The Europeans were astonished at the fact this multi-platinum band who’d filled their lives were not known in the place where it all started

Depeche Mode have sold millions and millions of records, but they are still considered a cultish proposition on these isles. This year the band are on the road again. Five stadium shows in Germany; three in Italy. Three in France. But only one in the UK, at the London Stadium, the new home of West Ham. Yet this is still a triumph. It feels as if the band have struggled to escape their Basildon days in this country, the synthpop and the hair, the patterned shirts and the cheesy grins.

Only now does Martin Gore feel like the band are being taken seriously in the country they grew up. We’re in the kind of Mayfair hotel you’d expect a band like Depeche Mode to be ensconced in, fulfilling the last of the band’s press obligations in the promotional push for latest album Spirit. Gore seems relieved that he’ll soon be back in Santa Barbara, California, where his 13-month old and two-week old daughters are – he has only been with his youngest for 24 hours of her life due to band obligations. Spirit is emphatically humanist. A state-of-world summary that sounds like it could be about Trump or Brexit but was written and recorded before both were material game-changers, it gives apathy short shrift, calling for “revolution” no less. There is a beautiful lullaby (‘Eternal’). It sounds like a record by a new father and all the more interesting for it.

Gore cracks a wide Californian smile before launching into a unaffected yet still controlled guffaw that punctuates time spent with him (I’m told to expect it so am relieved when it first appears in our conversation). I’m telling him about the Depeche Mode cover band Speak And Spell that I caught at last September’s Essex Architecture Weekend, part of the Radical Essex project put on by Southend gallery, Focal Point. Their version of Dave Gahan performed in front of some blue Fosters cans that lined the front of the stage, a tiny barrier between the tribute frontman and the locals, architecture fans, Essex geeks and arts press all dancing to the ‘Mode’s early hits. Tribute acts are the real “folk” musicians, the dancing and singalongs they inspire keeping some kind of collective spirit alive in pubs and village halls nationwide. But it’s a fractured collective these days in the UK.

‘The Worst Crime’, the third track on Spirit, sounds like it is about Brexit, but wasn’t it conceived before that?

Martin Gore: It wasn’t written for that at all. For me, it’s a song about humanity hanging itself and the worst crime being the destruction of the planet, because there are so many crimes that we’re committing on a daily basis, but this is the worst crime because we are not just doing it to ourselves but we’re also doing it to future generations. And, like I say, we’ve had so much time to implement things, to put things right.

You recently had a daughter, did that affect the songs?

MG: I had one 13 months ago and one two weeks ago. I have five children, four daughters and one son. I think that has definitely affected me. A lot of the songs would definitely have been written before my 13 month old was born but while my wife was pregnant. There is one song on the album actually about her, ‘Eternal’, which talks about caring for a child, but which also mentions the black cloud rising and the radiation falling.

How pessimistic are you about the future with Trump being elected?

MG: I was really pessimistic up until a few weeks ago. I now have a glimmer of hope because maybe the American system works, because the the Muslim ban obviously didn’t get through, the judges stopped that. And then now his repealing of Obamacare got scrapped. So now I am just hoping that everything that he wants to implement is just going to get rejected.

You live in Santa Barbara. How did you end up moving from Basildon to Berlin to there?

MG: I think I was in Berlin 85-86, 86-87. Then I came back to London, from 90-95. And then I moved to Hertfordshire until 2000 and that’s when I moved to Santa Barbara.

I once spoke to Alison Moyet, who also moved Hertfordshire. I remember she told me how in Basildon the milkman would come round to get autographs and wouldn’t stop hassling her so she had to move away.

MG: Yeah I used to live not too far from Alison. We only left Hertfordshire as I was married to an American [Suzanne Boisvert] and she had lived here for 11 years wanted to move back to America. I thought, ‘OK, I can’t really get out of this one.’ It wasn’t my choice at the time. We got divorced almost immediately, but we have children together and my son is still only 14 so I see him every other week when I am at home.

England never felt claustrophobic for me at all. I think it would feel more difficult for me if I lived in mainland Europe. America I think is really easy because Los Angeles has film stars everywhere and musicians and Santa Barbara a lot of people have homes there even if they don’t live there. You are kind of inconsequential, no one cares.

How do you view political changes in the UK. Do you feel you get a sense of what is happening?

MG: Obviously I understand the bigger changes, but I think it’s more the smaller stuff that’s going on … I don’t feel part of it and I don’t think I have a right to. I’ve lived away for 17 years. I didn’t vote in the referendum because I think there was a rule, I think somebody told me was a 15-year limit. But I would have voted Remain.

Did it surprise you that where you were from in Essex voted to leave the EU at such a high rate? Basildon voted over 68 per cent to leave the EU.

MG: Yeah, it does surprise me, but I really think that people were fooled. A lot of people believed in the idea that all the money that was going to be saved from the EU was going to go to the NHS. It was a lie. And, in a way, they should redo the referendum as so many people voted on that. And the other thing, Andy in the band said this to me, and he’s absolutely right: even somebody who really understands the world of finance didn’t have any idea about the implications of that vote. If you’re gonna leave that to the general population to make that decision it should have been a minimum of a 60/40 split. It was so close, virtually 50-50. Such a huge decision and so many things hinge on that decision – but that’s it, it’s made.

There’s always been a split with the people in the UK who feel a cultural affinity with Europe and the people who don’t. I guess you always had a cultural affinity with Europe?

MG: Yeah. Most people at school I went to in Basildon didn’t take French very seriously. You would get laughed at even if you just put on a French accent, but taking [the idea of] German was completely laughed at. And then I took German, which was new at the time, one of the first people at the school to. When I was 15 I went to Germany on a school exchange. I felt an affinity with Europe before I was in the band.

A few years ago I wrote about a Depeche Mode themed guided tour of Basildon put on by Vince Clarke’s former girlfriend Deb Danahay. It was striking how many German, east European people there were, whereas the locals were nonplussed.

MG: I know Deb. I don’t know what it was that made us take off in those countries. If you go into the eastern bloc countries we are huge, and in Russia. Maybe there is something about the depressing nature of our music and lyrics that some people find an affinity with.

Do you think the UK has a cultural need for stasis and nostalgia, which means people don’t pick upon your messages so much?

MG: I don’t know. When I first started writing this album I realised that I was going down a dangerous route, because it is more about social commentary/politics. But funnily enough, 99.9% of the reviews I have seen have been amazing. I don’t know if it is just this album but gradually over time we’ve become more accepted and acknowledged in the UK, whereas in Europe we were embraced much quicker and for longer. The fans who get on the bus to go round Basildon, they’ve travelled there. I don’t know if they’re expecting to see Graceland but believe you me I didn’t live in Graceland!

It fits with this idea of Depeche Mode as the biggest cult band in the world but there currently seems to be a new wave of critical reevaluation for the band.

MG: I’ve noticed it particularly with this album, like I said. I think we have slowly got better press over the years [in the UK]. One of the things we did wonder about is if we were trying to lose the albatross of the early pop days. We were bigger here with Speak And Spell than we were in Europe, we were bigger in Europe around Some Great Reward, so they don’t remember that. So that embarrassing point still haunts us – that’s one of the things we think about but it’s probably nothing to do with that. But people probably don’t really care.

What songs are we talking about?

MG: We were really bubblegum pop when we started out. So Speak And Spell, A Broken Frame, ‘See You’, ‘Meaning of Love’.

When Vince left just before that period was there a sense that you might have to go back to the commuter job if things didn’t work out?

MG: There were a couple of songs on A Broken Frame that I had written before for another band that we thought were quite good that could be used. Some of them I just made up as I went along in the studio. That’s why it’s my least favourite album. I was dropped in the deep-end with it. But I was young and I did relish it really to be honest – it was fun to do. And it wasn’t like we worried about it when Vince left because of the naivety of youth.

Did you have backing from the label?

MG: Yeah. We were on Mute so it was an independent label, it was Daniel Miller, who is still involved with us to this day, he’s one of out best friends. We never thought about it at the time and fortunately the first thing that we released after Vince left, ‘See You’, was really successful.

Going back to the album, when you sit down to write, are you writing from a certain character or position, or is it just instinctive.

MG: I think it really is me trying to do something organically as I possibly can. I start playing some chords on a guitar or a piano and get something on the computer and I just start singing along. And that somehow ends up going from a verse to a chorus and then that’s the start of a song. But sometimes I’m not 100 per cent sure where the words are going. They’re not actual noises I’m making, they’re words. I’ll look and I think about where I am going with that. And then start again, the same chords, try and get another verse, get to the chorus… Without wishing to sound like a hippy, sometimes I think that you tap into something.

How did you first start songwriting?

MG: Somebody taught me two chords on a guitar when I was 13 and then I got a book and learned the rest of the chords. I used to buy Disco 45, a magazine that came out weekly or monthly. It had all the chart’s hits in it, the words not the chords. And I used to sit there from the age of 13 to the age of 16/17 or whatever and work out all the songs. At the same time I was writing songs myself. But I think that was great training because you learned the structures of songs subconsciously. By learning everything in the charts at that age when you are like a sponge it must have been good for me.

The London stadium gig – are you looking forward to that as a kind of homecoming as you were born not far from that neck of the woods in Dagenham?

MG: I was actually born in London, Hammersmith hospital. Then we moved to Dagenham, then Basildon. We’re particularly looking forward to it as it’s about time we made the step up from what we’ve been doing for so long. We usually do three nights at the O2 or something. We probably could have done this the last tour or the tour before but even with this one we felt it was a little bit of a risk. But we keep having to extend the capacity: I think we’re up to 68,000 now. My mum’s not very well so I don’t know if she will come this time, but my sisters and my kids and their kids and lots of friends. Because we’re just playing one show, we’ll probably know half the audience!

Spirit is out now and Depeche Mode’s world tour starts in May