I ring the bell on a blacked-out door in a pleasant Bloomsbury side street. Martha Skye Murphy answers, opening it to reveal the kind of art gallery you’d walk straight past if you weren’t paying attention. It belongs to a friend and today Murphy’s serving as its sole member of staff, sat at a desk that’s tucked away in a corner next to the wall that separates us from the outside world. It’s a thin wall, so the clangs of supplies being unloaded for the café next door, snippets of conversations in different languages as people walk by can be heard loud and clear. Murphy enjoys the seclusion, she says, eavesdropping on the comments visitors make about the art after they leave, assuming they’re out of earshot.

In direct conversation, however, Murphy’s far from elusive. She is direct, focussed and articulate, and enjoys the interview process. “As well as being an ego boost, it’s also quite therapeutic and very clarifying for me when I think about what it is that I’m actually doing,” she says. Her debut album is all about that process of clarification, she explains, not necessarily the revelation of answers, but the act of looking for them. “The songs are all trying to grasp at something, but I’m not sure they’re concerned with the idea of what it is they’re grasping at. What groups them is that fundamentally they’re all about not having the certainty of words to concretely explain something.”

Its title, UM, is a sound but not a word, an expression that offers only doubt and self-interrogation. On the album’s cover it appears as if a subtitle in a foreign film. Above it, Murphy is photographed sitting at a lie detector test. It all feeds into the central tension that makes the record so intriguing – the push and pull between what’s revealed and what remains hidden. Murphy is both the eavesdropper in the gallery and the self-examining interviewee; she’s equal parts the suspect at the lie detector, and the unseen interrogator on the other side of the desk.

“I do feel like the songs are still revealing themselves to me. I’ve always been interested in rawness, vulnerability and mistakes, and I would hope that in surrendering to not knowing, I can reach that state of mind. I don’t think I realised this until recently, but I think the songs are the deepest form of exposure of me as a character.” She finds a thrill in that exposure, she says. “I enjoy being afraid of vulnerability, I find that quite an interesting zone. Like the moment before you go on stage, that mixture of nerves and excitement, not knowing how it could go, is something I find addictive, and that’s what I’m interested in getting to when I write music.”

Frequently, UM is an intimate album. Many of the songs contain clear references to love and desire. “I used to think that I was hidden behind these songs, but recently I realised that it’s pretty fucking obvious that… well I’m not going to put words into someone’s mouth when they listen, it’s whatever you want to extract from it, but this is a presentation of a very inner part of me and my soul.” And yet, given that guiding tension of revelation vs secrecy, it’s an album that still plays some of its cards close to its chest. “It’s the closest you could ever get to knowing me, but equally it’s the furthest away from me, because I don’t know whether [the persona on the record] really is me at all.”

Murphy shapeshifts throughout. Her voice is sometimes a cracked whisper, sometimes an operatic swoop; sometimes low and confident, sometimes cold and detached. On ‘Call Me Back’ it’s nothing more than wordless mutters and mumbles. Instrumentally the record consists of textures from across the fidelity spectrum, from voice memos and solo piano sketches to immersive field recordings and fully produced waves of multi-instrumental sound crafted with co-producer Ethan P Flynn. It even stretches out geographically, utilising field recordings and samples from New Zealand, Wales and New York. She is keen to explore spaces and states of mind where linear time is distorted and objective truth becomes slippery, like grief, loss, longing and nostalgia.

‘Theme Parks’ for instance, is inspired by the way fairgrounds and casinos are often built in such a manner as to create so-called ‘temporal distortion’ so that customers will forget the outside world and spend more money. Casinos, for instance, don’t usually contain clocks, pump in artificial daylight after dark, use red colour schemes and gentle, repeating music to lull punters into a trance-like state, provide free alcohol and snacks at exactly the right pace to keep people grazing, and lace the air with extra oxygen to help players stay alert. Though they deny it, it has even been suggested that some Las Vegas casinos have also released pheromones to encourage aggressive gambling. “The song specifically came from speaking to my friend who’s a graphic designer, who was given this completely random job to help design a pop-up magic trick at Harry Potter world in Florida,” Murphy says. “She was designing a suitcase which you open, and then somebody pops out of it. She told me this insane figure that bamboozled me, I couldn’t believe it, that they were investing something like a billion pounds into this single trick. She was saying you wouldn’t believe how much money they spend to have people in [the park] for as long as possible.”

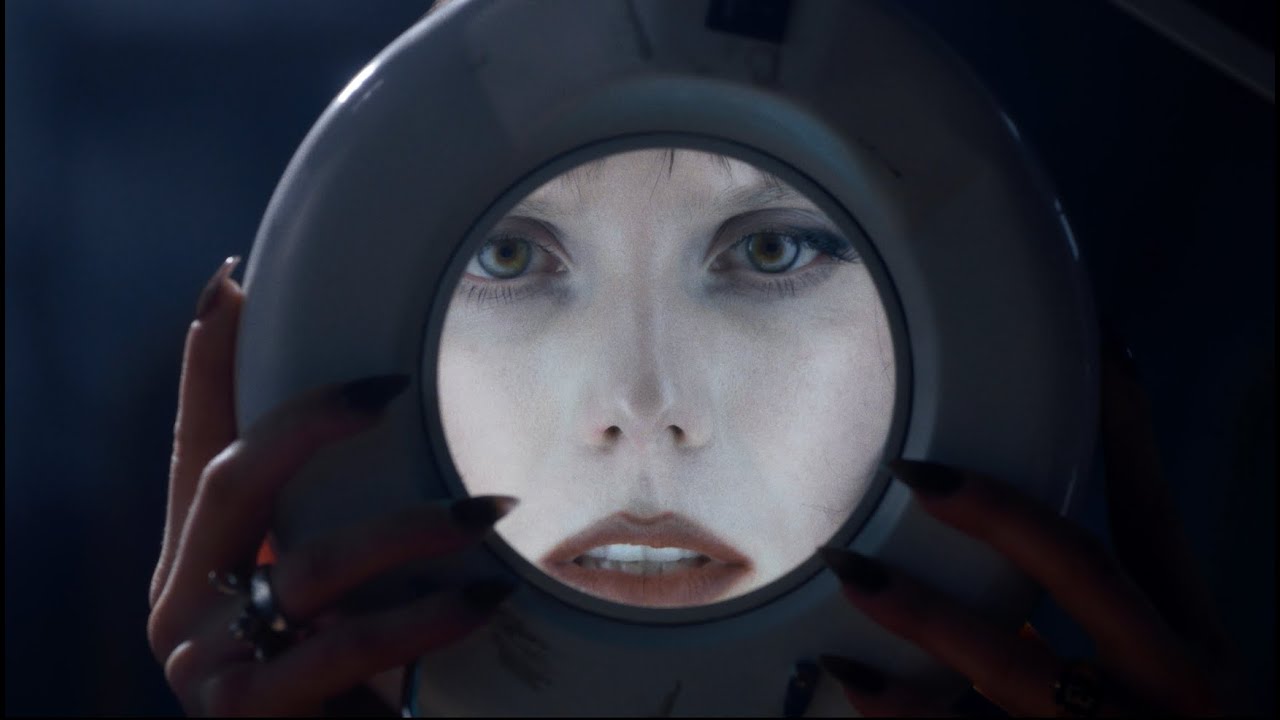

In a striking video for lead single ‘Need’ Murphy’s transformational skills are made visible. She appears as multiple different figures that externalise different aspects of her being – a feral creature who references Isabela Adjani’s character in the psychological horror The Posession, another figure she calls ‘the mole’ (both the blind animal and the undercover informant, a reference to both being ‘blind in love’ and to subterfuge), and a third who is a debonair mid-century spy. Films about Cold War espionage like The Lives Of Others – concerning a Stasi agent who becomes increasingly obsessed with the inner lives of the couple he’s spying on, were a key touchstone for UM. “In that film [the agent] has such an intimate access to their lives, but all through listening. I think that’s an interesting parallel, because I’m giving people potentially quite an intimate access into things that have happened to me, but it’s all through the ears.” The Cold War is reflected in the lie detector test album artwork, too. “That period is perfect because it’s all about secrecy, but also the absence of truth, the absence of information, and the invention of information in order to verify a false perspective that you’ve created. Always second-guessing, who has what, who’s better, who’s got more information.

For all the record’s intimate secrets, and however much its creator speaks about its songs as mysteries even to her, it’s worth noting that Murphy also exacts a meticulous control over the framework of UM. The album begins with what sounds like the click of a tape player turning on and a direct command from Murphy: ‘Commence’, before smoke-like strings and brass twist their way into shape. The album ends with another click and another command: ‘That’s enough’. The physical packaging of the record has been deliberately plotted too, not just that Cold War-inspired artwork, but a back cover where the track’s titles are arranged to resemble a table of contents, and an insert containing lyrics presents them as if they’re endnotes. “I wanted to reference literary forms where there’s a distortion of reading, like with footnotes and endnotes, where you’re interrupted in your process,” she says.

“There’s a contrast between the way I approach the presentation and the performance,” Murphy continues. “I’m very in control of the artwork and the aesthetic in order to steer the ship. I guess you need a level of bureaucracy for somebody to feel safe enough to enter. Then, once you’ve entered into a corridor, you can choose which room you go in.” Again, it comes back to tension at the record’s core. “Like when I’m recording, it might come from this very pure state of writing on the piano, or a voice memo recording, or the humming of a city, but when it comes to the vocal performances, they’re controlled and performative. There are these distinct spaces for me.”

The result is a Pandora’s box of an album, firmly hewn on the outside, but containing a swirling cloud of the unknowable within, an intense haze that subsumes its listener, lurching them around time and space, disorienting them to the point that they must cling to the songs for dear life. To encourage the listener to take that plunge, however, is no mean feat. There are moments of immediate power – the caterwauling crescendo of ‘Need’, for instance, or a head-mangling blast of wailing electronic noise that hits like a solar flare at the end of ‘Kind’, the record’s halfway point – but they’re built to at a gradual, wandering pace. To access UM to the fullest extent requires a level of patience and surrender that, some might suggest, is becoming increasingly rare in an age of record labels encouraging their artists to shorten introductions so they aren’t skipped on streaming platforms, and Spotify’s CEO is claiming that “content” costs “close to zero” for artists to create, and that it’s “not enough” for musicians to spend a few years between albums.

“The industry is in such a weird place that I think it’s almost brainwashed me into being cynical about the capacity of music to connect,” Murphy says. She’s been told by some, she continues, that the all-out assault of ‘Kind’, rather than the slow build of ‘First Day’, should be the album’s opener to maximise appeal to those listening quickly. “It was all, ‘You have to start with the banger,’” she recalls. “Well, no you don’t! You can do whatever the fuck you want. It was really important to me that ‘First Day’ is the first track, because I’m coercing someone into the state where they’re going to hear it in a sensitive vulnerable place.” She’s a hard artist to market, she concedes, “because I’m not spoon feeding enough for them to be able to see what the product is. I want to sustain a career and I want to have longevity and be able to make money from my work, but it does rely on a listener’s willingness to be vulnerable themselves. I need them to be able to submit.”

Martha Skye Murphy’s debut album UM is released on June 14 via AD93