Both as solo performer and as guitarist for cosmic synth explorers Emeralds, Mark McGuire has developed an immediately recognisable compositional style. His pieces are constructed in a loosely layered fashion that lends them a beguiling sense of fluidity – the beautiful ‘Brain Storm (For Erin)’, for instance, from last year’s Living With Yourself full-length, appears as constant flux, never remaining still for long enough to solidify properly. Above restless seas of sustained guitar and synth, a series of tiny, looped figures flicker in and out of one another, sending ripples skating across the music’s surface like the patter of rainfall. With Emeralds the same techniques are anchored by monstrous synth arpeggios and low-end rumble, but his solo tracks are detached from that group’s bass-heavy undertow and often appear to defy gravity.

That same sense of oceanic calm and weightlessness defines much of his music, and is a constant feature of his new album for Editions Mego, Get Lost, a cycle of sorts divided into a series of short pieces and sprawling closer ‘Firefly Constellations’. It’s a typical McGuire album in terms of sound, its first side very much a continuation of the moods and themes explored on Living With Yourself, but as the first of his albums to prominently feature his own vocals (on the delicately strummed, deceptively straightforward ‘Alma’) it’s his most accessible so far. The twenty minute ‘Firefly Constellations’, meanwhile, marks a quite distinct shift in sound, emerging from soft pastoral drone into a dense shower of arpeggiated synth.

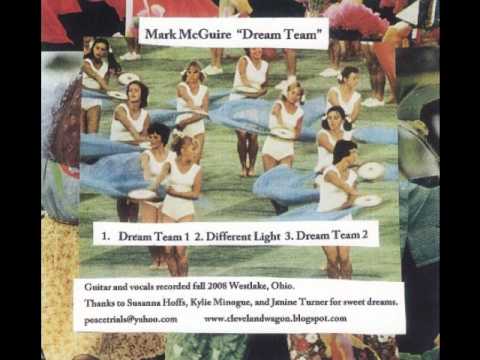

Earlier this year Mego also put out a compilation of McGuire’s earlier music, A Young Person’s Guide To Mark McGuire, a formidable introduction to the sheer breadth of his back catalogue. Gathering together tracks from across a huge volume of rare CDRs and cassettes, it covers everything from longer and more developed pieces to short experimental sketches. So across its length you encounter heavily distorted desert jams (scorched opener ‘Dream Team’, the chugging expanse of ‘Flight’) and epic sun-dappled psychedelia (‘Time Is Flying’) interspersed with exquisite miniatures like ‘Slipstreams’ and ‘The Lonesome Foghorn Blows’. With their compression of themes into one- or two-minute long vignettes, they’re akin to a series of studies on the wall of an art gallery, each involving in its own right but each adding its own modification to a larger, more complete piece.

With A Young Person’s Guide sixth in our list of the best reissues and compilations of 2011 so far, the impending release of Get Lost and a collaborative LP with Ohio duo Trouble Books doing the rounds, it felt like an appropriate time to catch up with McGuire. This interview took place via email over the course of several months, gradually layering up with the arrival of each new release – a process that pleasingly mirrored his compositional style.

How did Get Lost come together, and what’s the writing process been like?

Mark McGuire: Get Lost started as an experiment with psychedelics in June 2010 that led to the discovery of ‘Firefly Constellations’, and new sounds I had never made with my guitar before. After that I was on tour for a few months, so I let the song I recorded marinate and the ideas for the album started becoming clearer. I recorded the title track in January of 2011, which kicked off the vibe of the A side in my head, trying to meld the electronic sounds of the guitar synthesizer with the organic elements of the songs that I write. ‘Alma’ is a riff from a song I wrote in 2007 and have recorded a couple times a couple of different ways but had never released. There was almost a version of it on Living With Yourself but I ended up not feeling like it fit with the rest of the album. It kept creeping back to me, and when Get Lost was coming together it made perfect sense.

Are there any particular themes you were keen to explore with the new record? Sonically and in terms of mood, to my mind it feels like a continuation of Living With Yourself.

MM: Like I said, I really was feeling the electronic sound of the guitar, the synthesis of that with acoustic elements, and adding vocals on top for more depth and to give the songs a more specific feel. The album itself is about all of the layers of life blurring and melding together into what becomes the psychedelic nature of existence, and the cosmic links between mind, body, spirit, and mother earth, how the energy we contain is the same energy that stretches out to the deepest regions of infinity, and stretches back to the innermost subspace of the human soul. Once the lines start to blur and the planes start to merge, you can sit back and completely, well… get lost!

It’s also about losing track of your path, and the people in your life. ‘When You’re Somewhere, You Ought To Be There’ is touching on the idea that a person can be somewhere physically, but actually not be there at all, and how that can be destructive to the person and the people around them – which is something we’ve worked with in Emeralds, on Does It Look Like I’m Here? and even some parts of Living With Yourself.

So how long have you been making music for? What first inspired you to pick up a guitar?

MM: Technically, I’ve been playing music since I got my first guitar when I was nine years old, but I didn’t really record very much until I was a teenager. When I was young, guitars were just the coolest things on the planet to me, I don’t know how else to explain it. Growing up hearing blues, rock and roll, heavy metal and punk music, seeing stuff like Bill & Ted, Airheads, Beavis & Butthead, all that just made me think guitars were so kick-ass. All I really wanted when I was a kid was an electric guitar.

You’ve got quite a distinctive sound and way of playing the guitar, layering up loops – was there anything in particular that inspired the way you play and compose?

MM: When I was younger, like in high school bands, I used to write lots of little riffs, and those were supposed to be the ‘interesting’ points in the songs. The songs weren’t based around heavy vocal parts, or incredibly fast or technical changes, just cool melodies that would come in and out at times. Those were the things that I focused on back then, and I feel like I’m still working on similar things now with riffs and harmonies. I feel like whatever ‘inner harmonic system’ that might be going on inside my head, which seems to operate very simply, has something in mind that I’m working towards, and always have been.

My main instrument in all my music is the guitar. I use vocals at times, and also run my guitar through synthesizers, which take away from the identity of the instrument, which people sometimes think is just a straight up synthesizer. I want to incorporate other instruments into my sound, and definitely will over time. I really just work with what I’ve got and what’s around me.

What’s your writing process like? And how does writing solo stuff differ from working with Emeralds?

MM: Writing music with Emeralds and writing solo music is very different, because of the collaborative nature of our band. Writing music for myself can come together many different ways. Riffs cycle through my head a lot and are pieced together over time, and working by myself gives a lot of room to change things whenever I feel like it, adding and subtracting things from songs until they finally feel right.

With Emeralds, having three brains working on sounds together digs up so many different results, sometimes we literally sit playing a part for what seems like hours, finding our own sounds in what each other are doing, and things keep changing and changing. Then we’ll stop and be like, ‘Okay let’s try to do something like that,’ and then when we try again it sounds completely different. It’s good for us to always be recording so we don’t miss things that will only happen once, although we still miss crucial jams from time to time. I guess when it comes down to it, writing with Emeralds is very similar to writing solo music – it’s just all that energy cubed!

A Young Person’s Guide gathered together tracks from across your discography. Why did you decide to compile them, and what did you want to achieve with the record?

MM: I had been thinking of putting together some of my more limited edition stuff for a while, but Peter Rehberg initially proposed the idea of making ‘A Young Person’s Guide’ to my music. We chose the songs we thought stood out the most and best represented the different areas of my style.

It’s a good blueprint for someone new to my music, who doesn’t feel like tracking down all those records at once, like I know I wouldn’t want to do! There are certain albums that I didn’t use any songs from, because I am planning on eventually reissuing them properly on their own, but these are some of my favorite tracks, professionally mastered for optimum listening and preservation. They span from my earliest release under my name, up until my most recent 2010 limited edition CDRs and cassettes.

As a compilation, it gives a pretty good indication of the range of sounds you cover with your solo material – what sort of things affect/inspire the way your music sounds at any given time?

MM: To me, music serves more than a thousand purposes, and can be used in so many ways. When I start a song, I think of whatever idea it starts with as the core of it’s being – whether that’s a riff, a method, a texture, anything. Then as I play, it starts to develop organically and realize its own identity and purpose. When I have all my tools available, I can basically go with however it’s feeling and shape things to my liking as I go along, so basically anything could be inspiring those moments. Sometimes I try to play to the atmosphere that I’m in, and sometimes I try to shape the atmosphere with what I’m playing.

So are there any particular ideas and themes you try to express in your music?

MM: Writing instrumental music that evokes specific emotions, and which actually sounds like the idea you want to present, can be pretty tough on its own. So with my albums I try to make the song titles fairly representative of the intent behind a particular piece. At the same time, I feel like people should be able to let the music take them wherever their minds decides to wander, and not have their imagination clouded too much by subject matter, so I try to find some balance between the two. Songs all have their personal meaning to me, some more obvious than others. I’ve written about things that have literally inspired me – books, movies, travelling, people I’ve known – or it could be something I’ve seen in a dream or altered experience. A lot of my music comes from everyday life combined with psychedelic and supernatural energy – which is how my world feels.

As an extension of that, Living With Yourself definitely felt as though it was addressing the past in some way (though the idea of ‘nostalgia’ seems a massive oversimplification), and using cassettes for releasing could be construed as looking backward for inspiration and ideas. Would you say this was true?

MM: The ideas that I expressed in Living With Yourself were things that had been in my head for a long time, both with the music and the content behind it. Nostalgia and things of that nature have always been a part of our music in some way, because our music is never about something that’s right in front of you. You always have to think about it in some way to get there. That’s more what it’s about, exploration through thought, remembrance, any kind of mental journey, rather than just ‘remember this?’

What are you up to at the moment? Got any more releases in the pipeline, or new music with Emeralds coming up?

MM: Right now I’m on tour with Emeralds, we’ve been working on some new material and have been discussing putting something insane together in the somewhat near future, so keep your ears peeled for that. I’m also editing down a record I made with Robert Turman and Aaron Dilloway, which should see release sometime next year. Of course there will be other things as well, and Inner Tube, my new surf album with Spencer Clark aka Charles Berlitz, is almost ready to drop, so get extra stoked for that one!