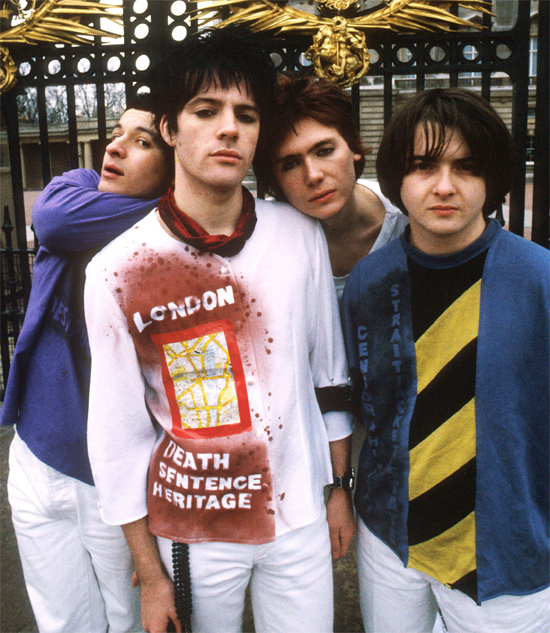

1992: White jeans – black hair – crippling self-consciousness – eyeliner and mascara – spray paint stencilled tops – star-jumping not shoegazing – aggressive androgyny – feminine machismo – so young, so impassioned, so sweetly ridiculous – nostalgic futurists revelling in contradiction – Sex Pistols’ situationist promise realised – intellectual Hanoi Rocks – we are all useless sluts, already lost – the only good thing on Top Of The Pops for years – blood red roses fall slowly to the dance floor – Bret Easton Ellis – Tennessee Williams – Sonic the Hedgehog – to see boys holding each other, allowed to touch each other gently, in intense idealistic friendship – bunk bed mentality – us against the world – lonely wreckage – monochrome dreams – narcissistic self-loathing – fake fur and feather boas – "old books are as exciting as records" – a million shattered icons of rock & roll purity – Axl, Slash, Public Enemy, Kerouac, Camus, Nietzsche, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Rimbaud, Marx – Iggy Pop, Beatrice Dalle – The Dead End Dolls – Rock & roll is our epiphany – Culture, Alienation, Boredom and Despair…

So, Nicky Wire; I can’t imagine that back then you ever thought that one day you’d be sitting here promoting a twentieth anniversary edition of Generation Terrorists.

Nicky Wire: Me and Richey definitely didn’t. Early on we felt a bit guilty about the master plan [to record one double album, sell sixteen million copies, and then spilt up], because it meant that all the musical ability of James and Sean was going to stop after one album. But we felt it was a master plan we had to implement. Whether we actually thought we could do it I’m not sure, but it gave us a sort of mental bravado to push on through. Because it was four working-class kids coming from Wales to try and change the world; it was a pretty fucking unbelievable story. We had to be larger than life, almost to the point of being cartoons. So in retrospect I guess we said a lot of things that were always going to be unfulfilled, really. Having said that, it was a fucking brilliant time! I’d love to feel the same power now that I did then, that fearlessness.

I suppose partly the whole thing about saying, "We’re going to do one double album and then split up," was just that you really did put everything you had to say at that point into it. It’s a good mindset to have when recording your debut album anyway; to treat it as though it’s going to be your last.

NW: Yes, it is. It’s almost like daring yourself to say fuck it, we have to put every bit of energy and dedication into this year and a half. And we were incredibly prolific really, from the time we signed to Heavenly to doing a double album… well, to be honest, right up to Everything Must Go. It was four albums in four years, it was like a sixties band or something. So I think we had so much… we thought we had so much to say, and it felt like our only chance, really. And six months later we were getting a big advance off Sony, and going into a residential studio with Steve Brown. We were ticking the boxes, all the bullshit we talked was coming true, you know. Cover of the NME, get signed by a major, we got on Top Of The Pops with ‘You Love Us’- so even though it’s looked upon as something of a failure, it actually achieved a lot.

Is it difficult to think back into the mindset that you had then?

NW: It’s not for me, because… I guess I am the band’s historian. I’ve kept all the fucking archive, and I’m still the biggest fan of the band. Despite my fucking body deteriorating, my brain is still the one organ that works perfectly well. I’m still that same person; I just manage to control it a bit more now. When it’s the three of us in the studio I’m still the same kind of hateful, horrible, slagging-off gobshite, but I try not to let that spill over. I can imagine how horrible I must have seemed, even though I was really a nice boy.

Looking through your old press it seems that during that period, or in the period just before the first album, you had the reputation of being the band party animal. I’m thinking of that James Brown piece for NME where you’re portrayed as being all drinking and shagging…

NW: And yeah, for about a year, from leaving university through the first year of the band, that’s what I was, really. But my body was so shit it just gave up, my liver packed in! I was only fucking drinking Babycham; it’s so un-rock & roll! We were driving over the Yorkshire Dales or the Lancashire Moors, and I just turned into a blubbing heap, I just wanted to go home and see my mum. I still feel like that a lot now, really. I was still living at home, and it was always a relief to get home. It was a different form of… I wouldn’t call it rock & roll debauchery, maybe on an indie kind of level it was, I don’t know. But I was quite happy to go with it, you know. We just felt so empowered at that time; it just felt like the four of us were so telepathically aware of our own roles. It was really kinetic. For four people in the same school to bond like that is a pretty rare and beautiful thing.

You recorded the album with Steve Brown, who is a real old school producer…

NW: Yeah, he’s really old school. As much as anything it was because he did ‘She Sells Sanctuary’ and that’s what we were looking for – a rock record that was also alternative, but just main-lined. And he did Wham! We just loved the idea of the ridiculousness of that, of mixing Wham! and the Cult. And there wasn’t a gigantic queue to work with us, anyway!

You managed to get the Bomb Squad to do one remix, but originally you wanted to get them to do the whole thing, didn’t you?

NW: We wanted to do more tracks, yeah, but looking back I’m not sure what they could have done with some of them. I think what they did with ‘Repeat’ was really interesting. It sounds really dated now, but yeah, all those things we were trying to do, at least it showed some sort of ambition. We were obsessed with Guns N’ Roses at the time; you can definitely hear that on the album, in James’ guitar playing… we’d gone from being in love with McCarthy and a lot of C86 stuff, but we just thought, that’s just a cul-de-sac, we’re not going to get anywhere at all if we actually make music like that.

Yeah; there’s nothing wrong with a rock record sounding like a rock record, but also it seems to work with the lyrics; even when the lyrics could seem like sloganeering, that glam-rock bombast gives the songs a slight ridiculousness that defuses any potential preachiness.

NW: Yeah, I know. If it had been slow acoustic tracks or something it would’ve just sounded like, "They’re trying so hard." Whereas I think the musical context did give it a sense of, just naivety really. And I’m really glad about that. We weren’t one of those bands that could just do a debut album like the Pistols, you know, it was never going to be our greatest album. It’s a folly, but in a good way.

And it’s an album that you could only really have made in your early twenties.

NW: God, yes. And I’m glad of the fact that at least it represents our youth, it doesn’t sound like we’re tired and cynical already. It does sound… revolutionary is a strong word, but it sounds inspired, it sounds like here’s a band with so many ideas and so much energy. It’s the one chance you get, to do it at that age, to just feel fearless. I just felt so brave back then, no matter how much shit we talked and no matter how badly sometimes me and Richey would play, to still think we could conquer the world… it’s a mixture of delusion and bravery, but I’d love to be able to feel like that again.

Looking back, do you think you’ve developed your craft lyrically since then, or does it stand as a separate thing that you’re still proud of, despite writing differently now?

NW: I think… it always scares me when you say developing your craft or something like that, because of course it’s true, but it’s something I really fucking fight against all the time! But I think on Everything Must Go, my lyrics had certainly found a better way of communicating, and obviously on The Holy Bible Richey’s had, you know. But having said that, I do think they stand alone as some sort of… I don’t know, we were trying to transplant all that Chomsky, Gramsci, Marx, Lenin stuff into lyrics, which is pretty hard to do, and there are moments when it really works, you know, and we’ll never be able to do that again. Because we’ve become fully rounded people with experience and travel and all that fucking…

It goes back to it being an early twenties album again, doesn’t it?

NW: Yeah, it does. And I think that certainly a song like ‘Crucifix Kiss’ which is mostly Richey’s, you can see that’s much more lyrical in the true sense, you know, that is a really brilliant lyric of Richey’s. ‘Little Baby Nothing’ I thought was brilliant, we wrote that together, and that really worked as a signpost to more formalised but really good lyric writing. But the hateful communist mantras are just like haikus sometimes, we always thought ‘Repeat’ was like a haiku. I remember we’d say that and we’d get bands coming up to us saying, "What’s a haiku? What are you talking about fucking haikus for?" It was only because we were interested and engaged. We lived in libraries and universities. We weren’t really trying to show off in that intelligent way at all; we just wanted to give people the chance to love what we loved.

And it was with Generation Terrorists that you first attracted these fiercely dedicated, incredibly loyal fans. In fact the ‘Manics fan’ almost became a youth cult in itself; like mods and goths, but just revolving around one band. There would be a handful in every town; usually intelligent, sensitive, mixed-up kids, and twenty years later those kids have grown up, and that album did actually change their lives, to some extent.

NW: I think it did. I don’t think we inspired any bands, but I do think we inspired people, especially in terms of education, I think we were like a litmus test! The reason we referenced so much and used all the quotes is that that’s what inspired us, and I think we did the same thing. There’s always someone who comes up to me and says I finished my dissertation on RS Thomas’s poetry in Wales or something. It just happens uncannily a lot. People send me their dissertations for their degree on the lyrics for The Holy Bible and stuff like that. I feel like a bit of an educational tool, like the Clash were, like Morrissey was to us. And I think you’re right; in every town in Britain there were people, and it wasn’t necessarily the musical genre they were after, it was buying into a lifestyle. And there hasn’t really been a band, apart from the Libertines maybe, who’ve done that in the last twenty years. There’s loads of good music, there’s loads of good songs, but there’s just not many good bands. There is a fucking difference.

How did it feel when you first realised that you were reaching people? When you started getting letters and seeing people dressed up at the concerts, and talking to them and realising that you’d made a really deep impact? I guess that was what you wanted to have, but were you surprised, or did you take it in your stride?

NW: I was a tiny bit scared, I think, especially after the ‘4 Real’ incident. Because that garnered an even more intense side of the fans, which was really good, because they looked fucking amazing, just like works of art, I guess like Richey was. But, I don’t know, responsibility isn’t the right word, but I was just a tiny bit dubious about it. But then again, the shows had become so… it felt like every fucking misfit in every town in Britain was turning up, really, which was what we wanted. It was constant stage invasions, it was our own mini version of Nirvana – obviously fucking a million times smaller, but it was people just finding something; finding an alternative that they wanted to buy into.

In terms of what you were kicking against in 1992, the perceived complacency of the tail-end of shoegaze or baggy or whatever, do you think things are better now, or are they in some ways worse?

NW: Like I said, I think music and taste and those kind of things, they probably are better. But I don’t think they’ve combined to form better bands. There’s loads of good radio, and the stations and all that, so you listen and you think oh, that’s a good sound, there’s an amazing drum sound, that sounds good… but you never ever think to yourself, that’s a fucking good band. They mean it. It’s a hard thing to explain I guess to a different generation, but we grew up with the idea of wanting to be Paul Simonon or Pete Townshend or whatever, you know, and you don’t really want to be the bass player in the Arctic Monkeys, do you?

No. And you don’t get bands with manifestos anymore. You don’t even get bands dressing up much or having much of a visual image anymore. And there aren’t many people out there with strong lyrics, even though the music’s good.

NW: No. You’re right there. I mean, with the lyrics, we over-stretched ourselves at the time early on and some of it doesn’t work, but with something like ‘NatWest-Barclays-Midlands-Lloyds’ which we were kind of laughed at for, it’s probably the most prophetic lyric we’ve ever written, you know. "Black horse apocalypse, death sanitised through credit" fucking nails it! Everything, in two lines! And unless you have that ambition, which we did, like I said, sometimes you fail but lyrics these days… it’s a totally dead art form. It really crushes me and depresses me, because I care so much about them like I said, and even when you fail, it kind of hurts really, that lyrics are just dead.

Why do you think that is?

NW: It just feels like music is a mixtape, really. A taste inducer to show that you’re actually a cool person yourself. And I like being uncool, I like being hated, that’s what the band thrived on. I think that’s disappeared, that antagonism, of Iggy literally baiting a crowd to fucking bottle him. People just love being loved. I think the digital age has allowed that, because you can measure your love on the internet. Your friends or whatever, and I think that’s had a big impact; people desperately want to be accepted. And that becomes… I call it ‘massification.’

Another thing with the internet is that you can move around picking up little sound bites of information. But when you put all of those quotations on the album sleeve it was still essentially the pre-internet era – it was there, but the likes of you and I didn’t really have access to it. So you had to actually read the books and know the stuff; you couldn’t just cherry-pick a load of quotes to make you look good.

NW: That’s really true. Richey never had a mobile phone, even. On The Holy Bible he was just devouring culture at such an exceptional rate, and we all… when you’re fifteen to nineteen, it has such an effect on your life, what you like then. It very rarely leaves you, and if it does leave you it tends to come back. We were just obsessed, whether it be with Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre, or Rumblefish, or Betty Blue, or Allen Ginsberg and all the beats. It was just this rush, this cavalcade of fucking amazing stuff. The weird thing about Generation Terrorists is that it’s an album inspired by total love and dedication to art, but it comes out, as it does with us, in quite a negative way, in quite a hateful way. Which is strange, because it is an album inspired by all the stuff we wanted to be.

And yet, as you say, there’s a sense of ‘We’ll never live up to that.’

NW: Yeah, there is! I think we almost wrote the myth of the band before we lived it. Which I like, again. I think we were probably the first post-modern band really, because we were just obsessed with everything, and that could be Tallulah Gosh or Rush, you know. We were so sick of the shoegazing… and then you had Swans, Young Gods… it was so fucking ghettoized, that music. It was never, ever going to be that great moment where Morrissey appears on Top Of The Pops, or Ian McCulloch rips his shirt, or Rod Stewart and the Faces kicking a football… that was just not happening, there was no alternative flipping over, and it just felt wrong.

It’s hard to convey that now, I think.

NW: Yeah, it is.

That idea that indie music was a ghetto, and you really had to try and break through and reach people. Because now of course people can look back and get all that stuff that nobody was listening to, and everybody is listening to those old Swans records and saying well this was great, and stuff like the Stone Roses and Britpop is seen as the point where it all got sold out and watered down. Whereas at the time it really felt like we’ve got to break through, we’ve got to make commercial records.

NW: It did, it felt like you had to challenge something. Obviously the mainstream, but also the ghettoization of… like, the Mary Chain for us were, we loved the Mary Chain devoutly and they managed to mainline in to Top Of The Pops with loads of fucking feedback and drug-induced performances. We always thought that was really the touchstones of what excited us, rather than liking something which is unbelievably cool and brilliant, and you listen to it by yourself. Which is great, and we’ve done that to the death with bands like McCarthy, [I Am A Wallet] is one of my favourite records of all time, but we just wanted to be more than that. We were just utterly obsessive, in every way, with ourselves, with everything else, with failure. It seemed like failure was an intrinsic part of us. I think it must be a Welsh melancholia, really. You see it in all the actors, there’s just a fucking self-destruct button. It’s like we know we can be shit, we’re not going to pretend otherwise.

It was also something of the times, wasn’t it, a reaction against the Thatcher-Reagan will to power, almost?

NW: Yes. Yeah, power is good, greed is good, all that. We did come from such a politicised area, we’d lived through the Miners’ Strike, Neil Kinnock’s constituency house was four doors down from James’s street, so we were really immersed. And we were really… analytical Marxist, trying to shove that into lyrics, like in ‘Methadone Pretty’: "I am nothing and should be everything," that might be lifted from Lenin, it might be What Is To Be Done. So it was pretty over-ambitious. The one thing we had going, because me and Richey had got our degrees in History and Politics, we did think that if it ever came to an intellectual showdown, we could hold our own. We’d meet people like Jon Savage or Simon Reynolds, who might not even have liked us, but we could talk to them for fucking hours on end, just about stuff, you know. We always loved talking to journalists, it was never that, ‘Oh, they’re going to fucking slag us off’ sort of thing.

You seem to get very mixed press at the time. There was this perception that the press hated you, and ridiculed you, but actually even the articles that start off like that often find something positive, almost like the journalists are finding themselves liking you in spite of themselves.

NW: They are. That’s the best way of describing it. They really couldn’t get our music early on. They really liked us as people, and they really thought it would brighten up their fucking world in all honesty, rather than doing an interview with Chapterhouse or Ride or somebody, where it was literally just talking about your fucking new effects pedal or something. It was just such a dull time. I always remember Chris Roberts’ review of ‘Motown Junk’: you could tell he didn’t really like us, he didn’t want to like us, but in the end he just said undeniably there is a rock presence, you know. That was enough, to be honest.

Yeah, or someone like Steven Wells, where it’s obvious you were just like a dream interview for him.

NW: Yeah, it was fantastic. I made no musician friends, really, but I met loads of people that I can still sit down and talk to, and they’re nearly all journalists, really. I just always thought musicians were really thick! You’d come across them and they just had no interest in anything, really. And I’d slag them all off, so they obviously fucking hated me, anyway. James used to say he’d have to run the gauntlet at every festival we ever did. I do feel bad about that.

You got writers at the time constantly comparing you to the Clash, which I think is quite lazy. You didn’t sound much like them, other than being a high-energy rock band, and at one stage you had the visual, the stencilled shirt thing. But while you wore your influences literally on your sleeves – you were like a collage of your influences – actually you looked and sounded like nobody else, especially at that time. And I think that you had such a strong overall package, it was as though that version of the Manics became a cliché after the fact. You had something so strong and individual that it was easy to parody, and easy to imitate. And so then you had bands like Fabulous and These Animal Men doing watered-down copies of it.

NW: Yeah, but the difference was, any band that tried to copy us then just didn’t quite get rock music. Rock as in Guns N’ Roses. We might have been rock to them, but that was the advantage we had, because the music press had gone so off the radar with rock music in general that we seemed like fucking Led Zeppelin to them or something! And we were still quite rudimentary, live especially. And that gave us a big advantage, because they were so easily shocked, they were such fucking twee, sheltered lives that it felt like everyone was living! That’s why we loved John Squire so much, because even back then he was obviously such a fucking amazing guitarist, you know, he was like Jimi Hendrix or whoever. But the ‘Roses in the music press were portrayed as this quintessential beautiful pop harmonising you know, whereas really the backbone of it was very, very rock.

And very political too, which was also ignored.

NW: Yeah, unbelievably political, and they still are now, Ian Brown just can’t stop himself when he gets on stage! And I think with ‘Repeat’ and ‘NatWest…’ we were… you can really fuck up writing anything political, it’s the hardest thing to pull off. Many times we’ve written them and they haven’t worked, but when they do work, like on ‘Tolerate…’ or ‘Repeat’ or ‘NatWest…’ there’s no better feeling. ‘Design for Life’, you know, it’s such an empowering feeling, to have condensed something you feel deeply about into three minutes of uplifting music. Why people don’t do it anymore is because it’s so fucking hard. Everyone will always take the piss out of anyone trying to do anything political. It’s just because they can’t do it. It’s the hardest trick in the world to pull off, you know, because politics is so diffused and messed up now.

And no-one wants to be nailed down as saying something, in case they get it wrong.

NW: Yeah, it really counts against you. It did with us, with Castro. Going to Cuba just fucked us up in so many ways. Countries that had broken off the shackles of communism obviously hated us for going to see Castro; America, visas, having a Cuban stamp on your passport, getting stopped constantly as if we were fucking terrorists or something… that really backfired against us in virtually every way, even though we really enjoyed it.

It’s off the subject that we’re talking about right now, but do you actually regret doing that, or are you still glad you did it?

NW: I’ve got many regrets. I’m not one of these blokes who says I don’t regret anything, because I was such a fucking gobshite when I was young. But I don’t regret that, because I just think it was original, odd, and we were never that… we were somehow portrayed as deluded communists who were endorsing the government, when all we wanted to do was be one of the first rock bands to actually play in front of people, to have a great adventure really, and to show that… we always pull for the underdog. We knew a lot about Cuba, we knew how good the education and the health was, the life expectancy was greater than the USA’s and it was constantly being portrayed as just a fucking backwards third world disaster zone, you know, and it actually had a lot of positives that we were trying to show. Yeah, we were socialists, but I don’t think we’ve ever come close to being communists.

I don’t suppose you can ever go into that situation without people trying to use you for their own propaganda purposes, on both sides.

NW: Exactly. Yeah, as a negative and a positive. And we didn’t even fucking care. It sounds really glib now, but it was just fucking rock & roll, wasn’t it? Have we got to such a tight, controlled place with music that you’re not allowed to make mistakes or anything, or break out of certain preconceptions? Have we literally just got to conform to what the tastemakers [dictate]? Like I said, being hated has always been a huge part of our inspiration, really.

Is it difficult as well to look back at those first three albums and it must be very difficult to see them in the way you would if Richey were still around. That must colour your perspective on it.

NW: I just think it’s hard to really comment on them in their entirety, because there’s someone who’s not here to say his piece, really. I’ve got my thoughts on it, but yeah, there’s a big… especially with The Holy Bible more than anything. And we were so tight on Generation Terrorists, you know. And I don’t think Richey was around long enough to actually look back on it with a sense of fun. Because we were so fucking ridiculous. In a good way. It was like the Pistols; the fabulous disaster. Even though there was an intellectualism there, it was clouded in this, ‘Are these guys for real?’ sort of thing. I look on it now as just really brave and naïve, and I really love it, but that’s only maybe come in the last ten years, really. So I don’t know if Richey ever had the distance to actually look back and think that we did actually achieve a lot of what we said; we didn’t sell sixteen million, but we were on the cover of the NME and Melody Maker, we got on Top Of The Pops, we gained gold records in Germany and Japan and the UK. We didn’t break like we hoped, but…

So did you for the first ten years really think of it as a failure, despite everything that you achieved?

NW: I think you can see on Gold Against The Soul that we just thought it was an utter failure. That’s why Gold Against The Soul is so hollow. It’s such an odd record really, it’s even more rock, it’s even more hollow and very sad, once you take away the bluster of the music. It’s like the dream is fucking over, that album. Whereas The Holy Bible is yeah, the dream’s over but the fucking nightmare’s good, you know, let’s face the truth.

And compared to those two, Generation Terrorists is a really fun album. It’s passionate and intense, but it’s like, you mentioned the lyric ‘NatWest-Barclays-Midlands-Lloyds’ as one that people took the piss out of a bit, but it’s a great line to sing along to!

NW: Yeah, and ‘Stay Beautiful,’ it’s just such a brilliant, naïve, punk rock radio record; when you hear it now it just gives you a bit of a lift. It just reminds me of the smell of the hairspray that I used to use during that era. I look back on it really fondly. I don’t know what else we could have done, really. I don’t know if you’ve had a copy of the anniversary edition yet, but CD2 has all the demos, and it’s definitely a case that some of the demos are better. They are rawer, but they’re still controlled, and I think we could’ve maybe gone a bit more down that route.

And at some point you decided – despite what you’d said in the press about splitting up after one album – that you needed to carry on with it. Was that a difficult decision, or was it just at some point assumed that of course you were going to carry on?

NW: I don’t think it was ever talked about. We’d done an American tour which was a disaster, and we were pretty demoralised I think, and then we went to Japan and it just blew us away. And then ‘Motorcycle…’ charted top twenty, we did an amazing Reading, and then we realised ‘Suicide is Painless’ had been top ten, and we thought fuck, we’ve had seven top forty hits in a year, we’ve played to 3,000 people in Japan and the UK, we’ve got gold discs from Germany and Japan, cover of the NME, cover of Melody Maker twice and all that. I sort of ticked off the boxes on my Lenin Great Five Year Plan, thinking: apart from America and the sixteen million, we haven’t done bad.

It wasn’t just McCarthy level, was it?

NW: No! And I guess doing it then, as opposed to doing it now, if you see how record sales have diminished, in terms of what we were selling we’d probably be playing the O2 or something! It was such a different era, I guess, but it did feel like a big breakthrough. And because I think about the band all the time, and I’m fucking obsessed, and I’m the historian… I guess everyone else just went with the flow of it, but I was constantly trying to see progress. ‘Little Baby Nothing’ was the last single – the seventh single or something off the album! And it just scraped into the top forty, and I felt, well, stage one has been achieved! Now we must industrialise, go on! I even used to speak to myself like Lenin or something, it was so stupid. You’re always told scare stories about record companies, but we actually sat down and realised, we’ve done every fucking thing we wanted. We’d released singles, we’d spent thousands on videos, we’d had our choice of producer, everything. We just thought, what are we worrying about? And I’ve always thought, to this day, it’s such a relief for a record company when a band actually has a strong vision. It’s just a relief, because they’ve got to do less. It’s just fucking idiots who think the music is all that matters that get manipulated, really.

Yeah, I suppose if you go in and say, we want to sell sixteen million records, the record company is going to say "excellent! Let’s get started!"

NW: Yeah, and you know, whether it’s Pete Townshend or Neil Young or the Pistols, a lot of our heroes, they did what they wanted to do and the record company made money off of them. It’s quite a simple equation, really. No-one’s more fucking hardcore than Neil Young about stuff like that, but he’s always been on a major record label and he’s always navigated himself through the shit. It just takes a bit of effort, but… I think people are longing for the days when majors signed more bands at the moment, really, because they’ve got no money. But that’s another conversation…