Although London based and born, Lynks owes his confidence to Bristol. It was a formative experience studying in the city, he tells tQ, where he was embraced by a close-knit music scene that remains particularly welcoming to fledgling artists, and where the project was formed at a basement party, then a flurry of chaotic choreo and DIY outfits. “I think it says something about the openness of Bristol. I think if I hadn’t had the reception that I’d had at the first Lynks gig, where it was really mindblowingly positive, I probably would have been like, ‘Well, I’m never doing that again,’” says the artist, whose outlandish performances have been bringing joy, an abundance of innuendo (looking at you, ‘How To Make A Béchamel Sauce’) and a lot of sweat both on and off stage ever since.

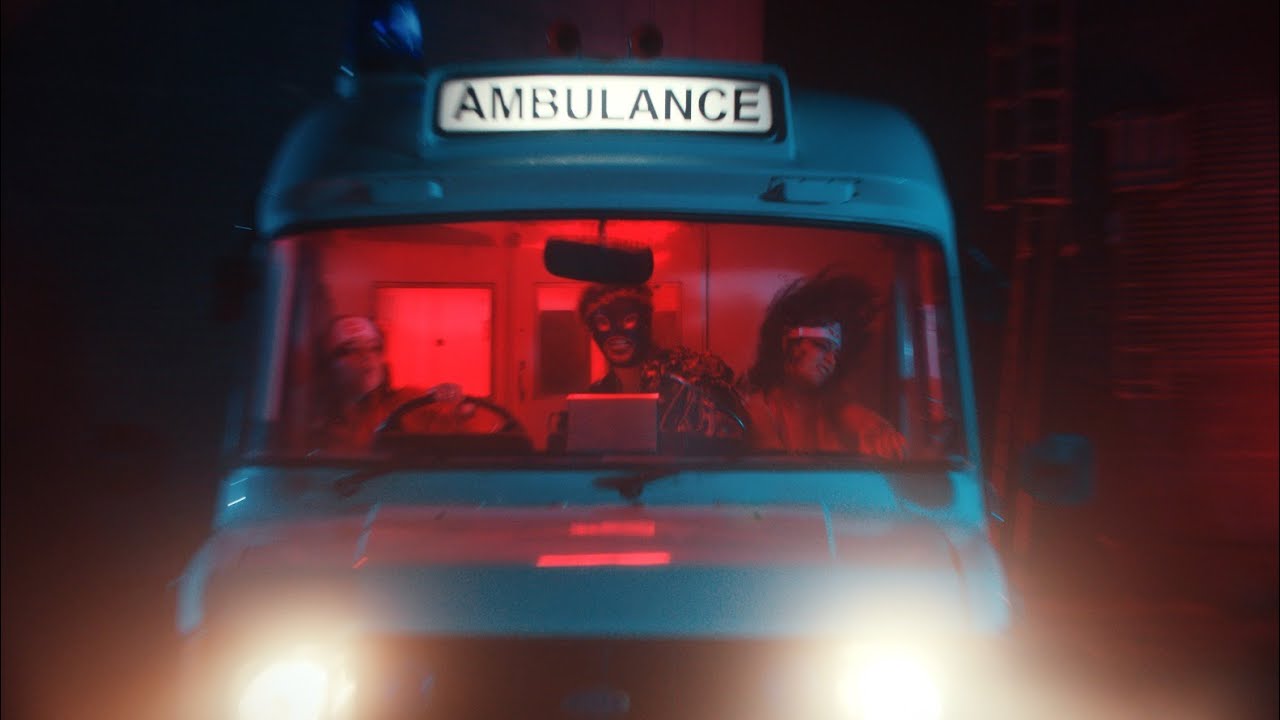

Queerness and so much of what that entails – the sticky hook-ups, a ride of pride on the DLR, and discrimination within the NHS – are all touched on in Lynks’ debut album Abomination, due next month via Heavenly, and in our conversation. A self-proclaimed comedy singer, his lyrics are quick-witted and elastic, moving deftly from joyful abandon to struggle. When sexuality comes into conversation, so does gender. Male-presenting in his day to day but gender fluid when performing, Lynks’ theatrical gender-bending outfits have drawn a crowd, both online and in person, having been highly elevated since early days of binbag extravaganzas and rubber glove gowns.

Camp, glamorous, and always masked, Leigh Bowery has been a longtime touchstone. What’s new on Abomination are the shades of grey, the bad one night stands, discrimination and religious shame; the track ‘Leviticus 18’ features a reading from the Bible passage of the same name – “You shall not lie with a man as with a woman, it is an abomination” – before the album’s title track throws it straight back (“You best believe I’m on the guestlist for the armageddon.”)

It’s partly an effort to carve out something new within the mainstream queer narratives, Lynks says. “You don’t really get to live in the middle. So, I guess if I’m doing anything, I think it’s being fabulous while being incredibly depressing. Lynks is very camp, flamboyant, dramatic, celebratory, but I’m talking about things that are awkward, embarrassing, and real. It’s not watered down.”

So, let’s start with how the idea of Lynks germinated. Can you remind us of your origin story?

Lynks: The very simple version of it is I was keen to do club kid-y drag. I was making much more conventional music before, James Blake-y sad boy music,and I had a bunch of beats on my laptop that were a bit crazier – stuff that I was making for fun – but I didn’t think anyone would ever like them. One day I showed my friend, and he was like, ‘These are better than anything else you’ve made, you should be doing this.’ He happened to have a spot that had just opened up on this electronic dance night he was throwing in a friend’s basement. He was like, ‘Why don’t you do something with these beats?’ I obviously showed up covered in bin bags, like, ‘I’ve created a character now’. That was the first Lynks gig: I’d got three of my friends, wrapped them in bin bags to be Lynks Shower Gel, my backing dancers – a constantly morphing entity of different people.

Having been so used to an audience half paying attention and clapping when they were meant to clap, suddenly doing this gig and having everyone smiling and laughing and having the best time and dancing, I was like, OK, I’m never going back.’

You’ve been back in London for five years now. Can you tell us more about the queer scene there?

L: London’s obviously got one of the most ridiculously vibrant queer scenes in maybe the world. I think what’s interesting about Lynks is when I was starting out I was performing a lot of drag shows and things like that, but it quite quickly switched into the music world. I don’t know why, I’d still love to play more drag shows, but it didn’t really happen that much. So, weirdly Lynks kind of doesn’t live in the traditional queer scene as much as I’d like it to. Though there are a few big exceptions: Queer House Party is a big one. They’ve booked me a ton of times and honestly it’s probably one of my favourite places to play. They’ve created such an insanely amazing space there. So inclusive. I love them.

But the queer scene in London, I mainly experience it as a punter. I fucking love Riposte and that whole scene is really fun. It makes me feel old already. Even though I’m only 27, because everyone’s a fucking student, but I do love it. And obviously, The Glory has shut down now, but [their nights] Lipsync1000 and Man Up. I think the best show that I’ve actually ever been to was probably the final Man Up. That was fucking mind blowing. There was someone called Dairy King who came out dressed as a milkman and did Kelis’ ‘Milkshake’, and then revealed that they had udders on their own body and then milked themselves into cups and gave them to the audience. It was fucking sensational. They had little nipple tassels on their udders.

Masculinity was a theme of your EP Men, and it feels like an important theme throughout, but is Lynks more of a gender queer creation?

L: I don’t like labels, but there’s definitely a fluidity to Lynks. I really like to play in the extremes. It’s really fun to one day be giving the most masculine biker, leather jacket, energy, and then the next day to be in a fucking wedding dress in the ‘New Boyfriend’ video. What’s fun about Lynks, and the reason that Lynks is so liberating for me, is that if I wasn’t in a mask dressed up, I wouldn’t be able to get away with any of the shit that I do. And so that makes it really exciting to play in the extremes of masculinity, but the extremes of femininity as well.

You’ve described Lynks as an opportunity for you to tap into the chaotic, feminine, angry side of yourself.

I think that we decouple femininity and anger a lot. I think anger is seen as a masculine emotion. And it’s seen as “unattractive” for women to be angry. And I think that, as with all those pressures towards women, there’s a version of them that comes towards anyone that’s feminine, or anyone that society views as aligned with femininity. So, a lot of misogynistic things hit gay men in similar ways. Gay men don’t really get to be angry, they get to be ‘sassy’, or ‘bitchy’, or whatever, kind of the same way that women are ‘shril’ or ‘bossy’. I think anger can be very healthy. It’s like a important way to exorcise things. It builds up inside you if you don’t give it to other people, and then you turn it on yourself. So, as a queer person, I’ve got a lot of anger about this world that we live in. I think everyone needs an outlet for that anger, and Lynks is a really productive outlet for mine.

On femininity, I think your fashion leans into it. The ‘CPR’ video references the Comme des Garçons SS 15 collection by way of Mad Max, so there is some masculinity to it, but for me anything super flamboyant just is quite feminine. Maybe it’s because I think of femininity as quite a wide spectrum, a catch-all for anything that’s not hegemonic masculinity.

L: I think it’s almost the flip side of that, isn’t it? Masculinity is so limited that if you do anything outside that it will automatically get lumped into femininity because we are in a binary. Anything that isn’t trousers and a shirt? Basically, it’s going to be feminine. I fucking love that look, I was very proud of that. That was Lizzie Biscuits, an amazing Sheffield designer. It’s a massive coat and trousers; it’s crazy that that ends up being feminine,even though I’ve got my top off, showing off a very male torso. It’s even a bit Lil Nas X. A lot of his looks are a take on a suit or something, but just because they’ve got rhinestones and bigger shoulders, they’re fucking with gender. I might add, it’s crazy how narrow the line is. Like how people get so up in arms about Harry Styles or fucking Timothée Chalamet just wearing a slightly different top with trousers.

You mention in ‘Use It Or Lose It’, that the breadth of identities of gay men over 40 is limited to either Ian McKellen or Graham Norton. Do you feel like Lynks is breaking stereotypes?

I don’t want to give myself too much credit. What I meant by that is the level of representation beyond your 20s is nil. I think that’s kind of always the case. You look at representation of people of colour until the last 40 or 50 years, a marginalised group where there’s perceived to be “no market for” their stories, and they’re limited to side characters and best friends. And that essentially means that you don’t have any model for what your life looks like. I think we’re now starting to see that it’s changing for queer people in the last 10 or 20 years. We started to see queer stories appear on screen, and we’re starting to see models of what queer life looks like full stop. But that still hasn’t reached old age or even adulthood, really. All queer stories are basically just 20-something really hot men. Occasionally we get an age gap lesbian relationship which is great, but not much. I actually just saw All Of Us Strangers last night, and that’s one of the first times I’ve seen a 40-something gay man being represented in a piece of film.

That song is about wanting to have more sex in your 20s because you feel like you’re going to be old soon and no one’s going to want to fuck you. And wrapped up in that is the idea of ageism in the gay world, and how there’s no place for older gay men because of exactly what we’re talking about. Am I creating a new way of being gay? I don’t really know. But, I was saying that the representations of being a queer person have been limited so far to either a really sad coming out story, or a really fabulous, proud, but two dimensional portrait of a happy gay man.

You keep one foot in queer club culture and the other in the more mainstream indie scene. How does that balancing act work without compromising?

L: It’s not a conscious thing really. It’s maybe just about my musical taste, which is very much 50 percent COBRAH 50 percent Mitski. So, naturally, my music that I make is going to have a bit of both in it. What’s been nice is seeing it naturally being picked up in both those spaces. That’s quite gratifying. Those two worlds do seem quite diametrically opposed, on the surface of it.

‘CPR’ takes a medical issue and makes it a bop. Was there a particular inspiration? A handsome doctor?

L: I was in a first aid course, a CPR class, and I just had the idea in my head. I thought it was really funny. I wish I could say this was some deep comment on the NHS. It’s just I’ve got a very dark sense of humour. And I’ve resisted doing a pure sexy song before. I was like, “Wouldn’t it be funny to take the most taboo unsexy thing one can write about – death – and turn it into a sexy song.” If you think it’s bad taste, you’re probably right. But I love it. I’m kind of amazed that it’s on the fucking BBC 6 Music playlist right now. It’s like they haven’t caught what’s going on.

I think for me, it’s interesting in the context of medical environments, where LGBTQ + people are still experiencing discrimination, and at the very least feel uncomfortable to be their fullest selves. I guess ‘CPR’ rebels against that.

Yeah, I guess it does. I wish I could say that was the intention of the song. It certainly is not. But, there’s a track on the album, which goes into that in a bit. There’s a line, “Just a teenager trying to make a blood donation, turned away based on my orientation / Now every time I see the British Heart Foundation, I’m reminded I’m an abomination.” That’s obviously about how until very recently, gay men weren’t allowed to give blood in the NHS and in America, which, is so beyond fucked up on so many levels. The main reason I think it’s fucked up is that all blood is screened for HIV, no matter who it was taken from. And what makes me even more angry is there are potentially men that didn’t know they had HIV that would have given blood and found out and been able to get treatment. So, you potentially denied gay men treatment for a disease that could save their life. And also it’s people’s discomfort with having gay blood because of the discomfort of what that means: gay blood. What’s been targeted there? The idea that gay blood is just inherently unclean? That’s one example of the medical establishment fucking with gay people. I mean, there’s countless more; need I comment on trans health care?

On the flip side, what brings you the most genuine joy?

L: Ah, so many things. I feel like in interviews, because there’s a lot of dark themes under all the happy shit, I often come across really depressing but I’m a very positive person actually. There’s so much – my friends, my boyfriend, my life. Like the fact that I get to do [music]. It’s so insane that this is my life. Being able to literally spend every waking minute thinking about how to make Lynks as sick as possible. It’s fucking cool. I love it.

Lynks’ debut album Abomination is released on 12 April via Heavenly Recordings