“At least I had some good sake,” jokes Lola De La Mata. “The rest is quite unfortunate.” The English-born, French-Spanish multi-disciplinary artist is recalling a dinner in 2019 that would change her life and her artistic practice forever. As she recalls, a staff member plugged in the restaurant’s electric piano without checking that the master fader was at 0, which resulted in a deafening noise. De La Mata had already been experiencing low-level tinnitus for years prior – she blames the heavy metal shows that her parents took her to growing up – but the feedback in the restaurant was so severe that it would leave her dealing with catastrophic consequences. “It was a rupture,” she explains. “Afterwards my hearing in my left ear kept going through notches, I’d completely lose my hearing, or low floating tones would cover [other people’s] speech. Sometimes I’d wake up because I was hearing all this thunder, a cracking sound.”

The thunder, she was later informed by audiologists, was a good thing – the sound of her ear trying to repair itself. This was of scant solace, given that as well as extreme tinnitus, De La Mata developed vertigo. “I do have a chronic health condition, which made it difficult to pinpoint if it was that that was suddenly getting worse, or whether it was [the damage to the ear] that was causing neurological changes, but I literally couldn’t walk straight; I was having what looked like strokes where I would collapse.” A violinist, she was told by doctors to give up playing. When the COVID pandemic arrived a few months in, she was forced to shield because of ultimately false suspicions that she had MS. “I got really frustrated,” De La Mata says. “I wasn’t getting any of the answers I wanted. It was, ‘Your hearing is fine, you’re young, you’re healthy,’ and it’s like, well clearly I’m not if I can’t walk and people are feeding me.”

Over a year later, when she had recovered to the point that she could hear again through her left ear, though not as well as before, she was able to start processing her situation. First came a composition called ‘KOH-klee-uh’ via SA Recordings in 2022, the leading release in a four-part series called The Hearing Experience in which artists were invited to explore their relationship with the act of listening. An uneasy and often jarring mixture high-pitched rings, deep scrapes and dull thuds, she employed tuning forks used during the Rhine & Weber hearing test, as well as a Canna Sonora, a rare instrument consisting of aluminium poles arranged vertically across a rack. “There’s a node in the centre, and when you rub [a pole], it activates a vibration. When you approach it with your hand, the vibration actually swarms into your palm, then you shoot it back. It’s absolutely wild.” In the process it delivers a ringing noise, equal parts grating and transfixing, that accurately mimics the sound of tinnitus.

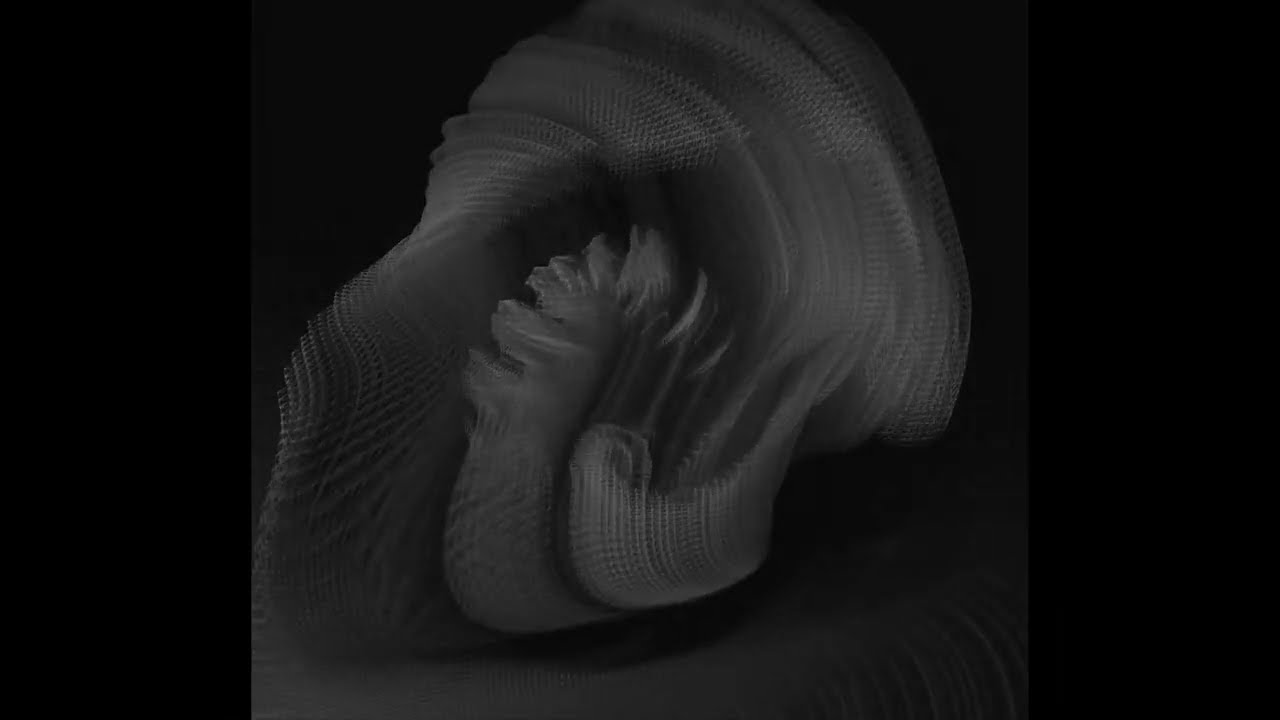

“At the beginning it was not a good project, it was just, ‘I hear a high-pitched sound, here’s a high-pitched sound!’” she laughs. The plan at that point was to create a number of pieces relating to different parts of the ear, but over time her scope broadened to become her new album Oceans On Azimuth, a visceral and intense thing that bristles with life in the same way her eardrum thundered as it tried to force itself back into shape. At the record’s launch at the Stephen Lawrence Gallery in Greenwich, a week before she speaks to tQ, De La Mata displays accompanying sculptures based on a 3D rendering of her ear canal while Jono Heale from the hearing protection company ACS takes similar moulds from attendees to form part of a future piece. Part of the venue is devoted to instruments arranged in preparation for De La Mata to perform following a panel discussion with Heale and the abstract turntablist Maria Chávez. There’s no Canna Sonora – only two of them currently exist in the country – but a number of the other instruments have been specially crafted for the project.

She begins her live performance by walking slowly through the crowd bearing one of them, a metal gong in the shape of an ear. It spins on its string as she strikes it, making the clanging sounds spin around our ears. As the resonances fade each time, the sounds of our surroundings – church bells, sirens, the crash of a dropped glass – feel amplified as they fill the emerging gaps. That is until De La Mata takes to the theremin, playing it first at a shrieking high, then low like a chainsaw. Suddenly it stops, and as a new electronic bass tone slowly builds the musician moves over to a violin, partly wrapped in tinfoil, which she plays scratchily and discordantly. She thumps the instrument with the bow, then scrapes its strings with the bow upside down. She scrapes the bow again against the rim of some hi-hats and knocks it against the inside of ear-shaped metal loops. Turning to her laptop she unleashes a monstrous barrage of beeps and gurgles and screeches from which a muffled rhythm gradually emerges. Occasionally recorded voices can be heard atop the fray. One is an academic-sounding figure who explains the concept of impedance matching – the way we have a ‘middle ear’ whose role is to take the vibrations that enter the ear and translate them so they can be interpreted through the liquid of the cochlea, through which sound travels differently. Elsewhere, a woman’s voice riffs on the phrase ‘pink noise’ – referring to an ambient sound that can be used in the treatment of tinnitus – which De La Mata has warped into a fragmented whirl.

The voices belong to two employees of The Hudspeth Laboratory Of Sensory Neuroscience in New York, biophysicist Francesco Gianoli and resident musicologist Lana Norris respectively. De La Mata had come across the institution when, a few months after ‘KOH-klee-uh’ and her first foray into making music around her tinnitus, she searched online for academics in the field of audiology. She was intrigued that the laboratory’s director A.J. Hudspeth “kept employing words from artistic fields, like how the way hair bundles are distributed on the cochlea is almost like a piano in reverse. There was something that was accessible, not just academic.” You can hear that same impulse in Gianoli’s explanation of impedance matching, too, included on the album and in her live performance, where he compares the role of the middle ear to the bridge of a violin. “He wrote a master’s paper about it, and how there’s a possibility of creating the perfect bridge for each specific violin if you put in the right equations with the thickness of wood, the type, the width, etcetera.”

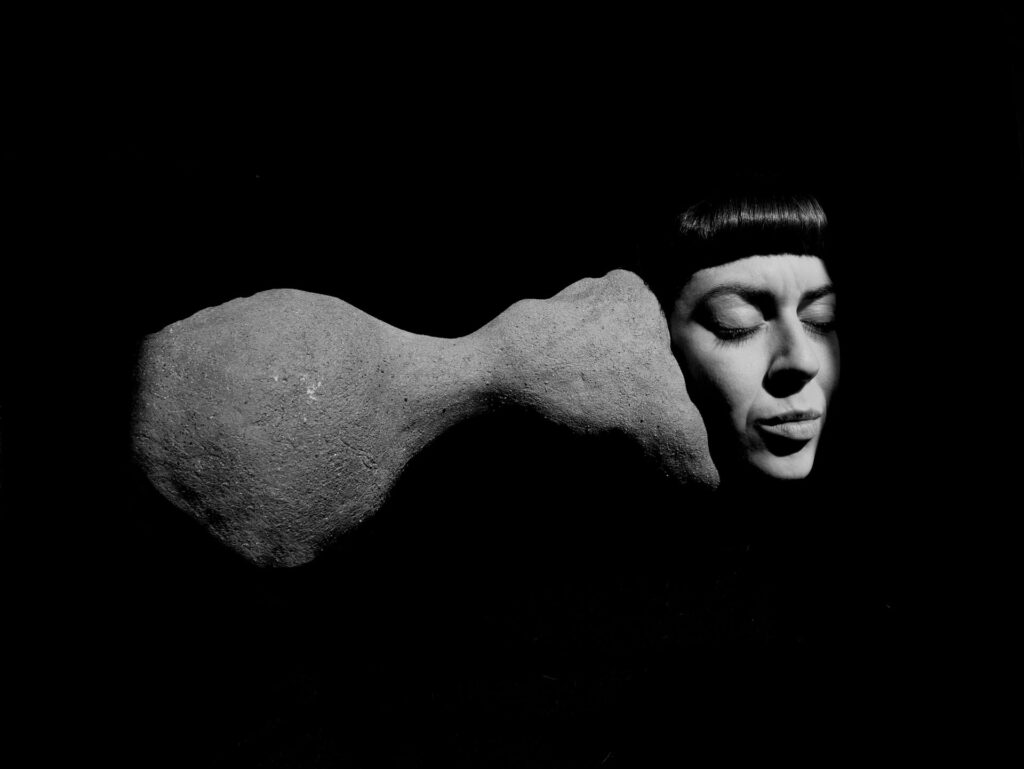

Throughout the project, De La Mata continues, she felt a duty to focus on this sense of the organic and the tangible, and not to rest too heavily on the digital. She became fascinated by the work of Maryanne Amacher, a composer and artist who worked with phenomena called auditory distortion products, or otoacoustic emissions, in which the ears themselves produce audible sound. “There’s a capacity of ‘playing the ear’,” as De La Mata puts it. When hearing the Canna Sonora, for instance, if you turn your head, it can feel like you’re catching extra tones that are being played, “like there’s a little moth fluttering on your ear,” whereas what’s really happening is that “your ear is pushing its own tone back out, it’s like a combination of the tones.”

She also started meeting with female double bass players (two of whom, Gwen Reed and Marianne Schofield, appear on Oceans On Azimuth). “There’s something about this oversized instrument that means if you’re a woman, who tend to be smaller than men, it means that your hands are used differently, your reach is different and the way your hips fit into the instrument, and that actually changes the vibration of the instrument.” There were parallels to be found, she explains, with the way in which different people’s ears will interpret sound differently due to their individual physiology. “We did a lot of experimentation, weaving tinfoil through [a double bass] to give it more distortion, slapping it and hitting it. I was just desperate to get into the ear. There’s a bit of, I don’t know if it’s the right word, but magic to how the ear functions, so it was nice to include instruments that felt surreal.”

Hudspeth was fascinated, and so within a couple of months of De La Mata’s reaching out, he invited her to join him in New York, which she did so thanks to an Arts Council grant. “I had already been meeting with instrument makers, so I already had some prototypes, so by the time I approached them I had something to come along with and discuss,” she continues. “They were desperate to show me all the things they’d built, these little studios, these mini-anechoic chambers, towers and towers of equipment.” One room contained zebrafish, a species who hear using hairs on their backs that are almost identical to the hairs on a human cochlea, and who are born translucent so that scientists can observe their nerves’ growth first hand. Elsewhere, the scientists showed her the 3D printed chambers they were developing to recreate the environment of a cochlea, “which was interesting because I’d been 3D printing all of my weird stuff. There was a lot of overlap.”

De La Mata had things to offer in return, pointing out how they might make use of soundproof rooms to deal with the noise produced by the fans of their machinery. Thanks to her experiments with an electromagnetic field recorder, which highlighted how noisy the lab could get, they were able to ascertain where previous experiments had run into issues. In turn, it also altered her view of science. “I’ve learned that it’s all about failure, and that they welcome it. People would open discussions by saying, ‘We have no idea how this thing works, we’re not there and we might never be there.’ And just as there’s a lot of failure in science, there’s a lot of failure in our communication, which actually allows spaces for questions, space to dream and innovate. So there was this common shared language, but we just had slightly different definitions of what it all meant, which was exciting. The last time I went to the lab, I met the head of the Paris branch of research at the Curie Institute that looks at hair cells and hair cell growth, and the way he’s studying it is by using etching techniques. In New York, they’re using photographic techniques as a way of measuring the movement of a hair cell. There’s no sure way or absolute truth to anything that they do, it’s all about experimentation and improvisation, which is not so different to what I’m doing.”

The most mind-blowing moment, not only for De La Mata but the scientists too, came when they managed to actually record the sounds that she heard in her ears – which now appear as ‘Left Ear’ and ‘Right Ear’ which begin sides A and B on the album – and in doing so opened up questions about the nature of tinnitus itself. “The NHS definition is that it’s a phantom sound that your brain is creating, that it isn’t something ‘real’, so you should try to ignore it.” By having De La Mata place her ear into an anechoic chamber, with an ultra-sensitive microphone perched in her ear canal, they were able to provide significant evidence to the contrary. “After the first recording of it, it was ‘There’s no way, this isn’t possible.’” They tried again with her breath held, and again with her tensing her ears, and again with other members of staff, but each time it became apparent that yes, the noises De La Mata hears are seemingly something physical. More intriguingly still, the two women whose ears were recorded, De La Mata and Lana Norris – the musicologist whose voice appears on the album’s ‘PINK Noise’, and who is also a choral director – were the only two people whose ears were found to produce spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. “It’s something to do with hormone difference, but they don’t really know why,” De La Mata says. Present in most children but believed to fade over time, they’re also found far more in musicians than in other adults, for reasons yet unknown. It all raises a lot of questions. “What I have is tinnitus by the definition we have now, but maybe that’s not correct. Maybe it’s something else,” De La Mata wonders aloud.

Given the scale of the unanswered questions, De La Mata has started a creative practice PhD to take things even further. For now, however, we have Oceans On Azimuth, a record that not only distils the complexity and nuance of its subject into an immediate and engaging listen, but also represents a major breach in the stigma that still surrounds hearing loss in the musical community. “If you’re told you have tinnitus, you’re often then told, ‘It’s the end of your career, you can’t be a musician anymore’, or ‘You’re not at optimal capacity’. There’s always a fear when you feel like you’re diverging from the normal with a body part or with health, or that you’re hearing something ‘wrong’. It’s something I experienced going to tinnitus support groups. Some people there were talking about tinnitus for the first time with someone other than themselves. There were people who had lost their job, who couldn’t see friends because they couldn’t deal with having any other noise. There were people who were suicidal.”

Oceans On Azimuth, however, offers an alternative way of viewing things: an embrace of difference and subjectivity and a rejection of a binary idea of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ ears. “It was interesting to have that other way of thinking about it. The more I speak to biophysicists, the more I’m learning that although you create something very crisp and perfect when you’re thinking about the purity of sound, your ear will still always add distortion to it.” Her tinnitus is retriggered all the time by the reality of everyday life, but now, she says, “I’ve learnt to accept it.”