Pink Industry live at Eric’s

On July 19 1984 The Mighty Wah! were the opening act on Top Of The Pops. They performed ‘Come Back’, then at number 28 amid a five-week stint in the Top 40, with bristling energy, a look of frenzy in their eyes and the kind of swagger imbued not just by a band, but by an entire city at its creative peak. Later that night their leader Pete Wylie barged his way to the front to witness fellow Liverpudlians Frankie Goes To Hollywood perform ‘Two Tribes’, then at number one. Frankie were also at number three with ‘Relax’, almost nine months after the track’s release, while Echo & The Bunnymen and Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark were not far behind. “So much of the Top 40 was Liverpool-based!” enthuses Wylie, 35 years later. “People always seem to forget that period.”

This was the peak of Liverpool’s most significant musical wave since the 1960s, the climax of almost a decade’s worth of irrepressible creativity. Politically and economically the city was in turmoil, with a Troskyist city council in open rebellion against a Thatcher government that had been urged to let the city slip into poverty through <a href="

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2011/dec/30/thatcher-government-liverpool-riots-1981" target="out">“managed decline”, while memories of world domination and spearheading the British Invasion were a distant but overbearing shadow; The Cavern club was pulled down in 1973. Yet among streets pocked with waste ground thrived one of the most exciting and vital music scenes Britain has ever produced, a resurgent second wave of Scouse brilliance.

Parts of this story have been well-told many times, the thrills and spills of the so-called ‘Crucial Three’ – Pete Wylie, Ian McCulloch and Julian Cope – for example, or the much-mythologised shows at central venue Eric’s by outsiders like Joy Division, The Fall and The Sex Pistols, yet despite being at least as vibrant a community as, say, Madchester or Merseybeat, this period has had no such veneration. A new five-disc boxset on Cherry Red Records, Revolutionary Spirit: The Sound Of Liverpool 1976-1988, is a valiant, long-overdue attempt to carve out this space in history.

The whole picture of Liverpool in that era is rarely painted as it is on this compilation: a city teeming with DIY spirit and bohemian inspiration, dozens upon dozens of musicians and artists around every corner, feuding and fighting, collaborating and cross-pollinating. The set boasts 100 songs by 95 different bands, from big hitters like the Bunnymen, The Teardrop Explodes and The La’s to long-forgotten unknowns with names like Brenda And The Beach Balls, The Turquoise Swimming Pools and Egypt For Now. Some of them hold up superbly to this day, some of them don’t, but all represent their own distinct corner of the lush and prolific breeding ground that was 1970s and 1980s Merseyside.

It’s a broad set, there are anthemic pop megahits that never were, blasts of bizarre and beguiling electronic experiments, pummelling post-punk labyrinths, bright, jangling scousadelia and everything in between, and among this sprawling, splintered scene there are myriad stories to tell. None of Pete Wylie’s projects appear on the set (aside from a brief piano cameo on ‘Faction’ by Faction) due to unforeseen rights complications but he nevertheless welcomes a chance to expand the focus beyond the more recognisable names. “It does feel odd not being on it, but I suppose it gives the rest of them more of a chance,” he proclaims, tongue firmly in cheek. “I want Liverpool music to be more widely remembered. Manchester had Tony Wilson who set up a tone about them, whereas we just splintered. The great thing with narratives is that nobody fits them but everyone’s part of it.”

Joe McKechnie, who provides some of the liner notes for the boxset and who played in groups like Modern Eon, Passage and The Wild Swans, speaks in similar terms. “It’s important to broaden the general consensus story of Liverpool. Even though it’s easier to research things these days, it still seems to get reduced to the same story every time someone writes about that period. This extends the story.”

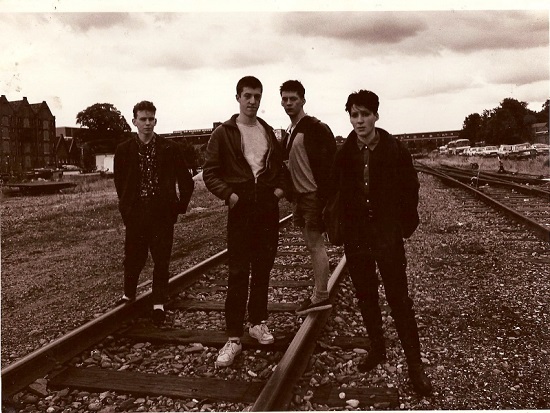

Barbel, photo courtesy of Greg Milton

There can be no band more overlooked than Deaf School, the catalyst for a generation. As Mojo’s Paul Du Noyer has put it, “In the whole history of Liverpool music two bands matter most, one is The Beatles and the other is Deaf School.” Their 1976 single ‘What A Way To End It All’ is the righteous opener to Revolutionary Spirit, a tale of suicide lathered in camp and cabaret with more than a shade of Roxy Music. The track would barely scrape the top 50 in the charts, but for many on Merseyside it was a blast of brilliant light. “The scene was of no interest to us until then, it was all pub rock and the leftovers before punk happened,” says Jayne Casey, another pioneer of that time. “Deaf School was the beginning of the change, they had that Bryan Ferry fabulousness.” Echo And The Bunnymen guitarist Will Sergeant agrees: “They were our Roxy Music, the ones who brought together art school and music. I think they were the ones that started it all.”

Deaf School’s Clive Langer went on to form Big In Japan, whom Jayne Casey would later join. At one time or another the group would also include Bill Drummond (The KLF, Zoo Records), Holly Johnson (Frankie Goes To Hollywood), Ian Broudie (The Lightning Seeds), Budgie (Siouxsie And The Banshees), Dave Balfe (Zoo and Food Records, The Teardrop Explodes, Dalek I Love You), Ambrose Reynolds (Pink Industry) and more. They were equal parts punk and performance art and would last barely a year, but the seeds were sown.

Meanwhile on Mathew Street in October 1976, Roger Eagle opened Eric’s. Previously based in Manchester, Eagle had moved to Merseyside a few years prior to run the Liverpool Stadium, an old boxing venue that hosted gigs by the likes of Captain Beefheart, Lou Reed, David Bowie, Dr Feelgood and Mott The Hoople, but sought a smaller club with his business partner Pete Fulwell. The now mythically-regarded Probe Records run by another key influencer Geoff Davis had relocated to Button Street around the corner that same year, while the Armadillo Tea Rooms were just down the road. These three locations would become the focal point of it all. “The triangle!” exclaims Wylie. “Where people got found rather than lost…”

There were other satellites of cultural importance, such as The Grapes pub, also on Mathew Street, Victor’s barbershop in the Chicago Building (home also to Zoo Records), the bistro in the Everyman Theatre and more, but Eric’s, Probe and the Armadillo were the most vital. The Armadillo was the control room, where bands, fanzine writers, artists and organisers would congregate over cheap pots of tea, swapping ideas, theories, proclamations and band members. “The Teardrops would be on one table, the Bunnymen would be on another table, we’d be on another table, it was just where everyone hung out,” remembers Jayne Casey.

“We’d fill the place and have one pot of tea between us which drove the chef Martin, who was also the bassist in Those Naughty Lumps, to despair,” says Wylie. “I remember celebrating once I could finally afford the bread and cheese! He’d try to kick us out but we’d make a teabag last a day.”

Probe Records was just around the corner. The shop’s reputation is notorious in its own right, thanks to the fearsome philosophy of absolute elitism and condescension to its customers – once they’d paid for their purchase, that is. Under the watchful eye of Geoff Davis, Pete Burns was its most notorious member of staff. “I was one of the people who wasn’t afraid of going in there,” says Gayna Rose Madder, one of the scene’s most forward-thinking artists with Shiny Two Shiny and A Formal Sigh. “I know some people were too scared to go in!”

Jayne Casey bursts into laughter when she remembers it. “It was like walking into another world! Most people’s memories are of either Pete Burns being really horrible to them or just getting served by Pete Burns. They’d just take the piss if you didn’t know what you were talking about. It was either an experience of horror or it was pure delight, but everyone remembers it.”

Send No Flowers, photo courtesy of Lin Sangster

When Burns died in 2016 there were entire Twitter threads devoted to his tenure behind the tills. “We don’t sell that shit in here!” he lambasted one unlucky punter in search of Rush’s 2112, while another was refused the right to even purchase a copy of a Half Japanese box set: “I’m not lettin’ yer waste yer money on that shite!” He would throw OMD and Buzzcocks singles across the shop and fell to the floor in hysterics when asked if he had ‘I Hate People’ by The Nowhere League. As for Julian Cope? “He’s a prick, but he’s our prick. Go ’ead.”

And then there was Eric’s, the only destination once Probe and Armadillo had shut for the day, save for a brief swing by The Grapes to “cadge drinks off local radio presenters”, as Wylie puts it. The venue hosted now-legendary gigs from Talking Heads, the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, Joy Division, The Fall and others, adding fuel to the flame of the burgeoning Liverpudlian groups that would follow. “A lot of Liverpool groups were still very conservative to what was happening elsewhere, where people were quickly moving away from the basic premise of punk into something else,” notes Joe McKechnie of those early days. “They started seizing the opportunity to do something a bit more experimental and artistic rather than just picking up on the template and reproducing it in a Liverpool style. When Mark E Smith died I immediately remembered a quote from an Eric’s gig in 1978, he used to talk a lot more in between songs back then. He said: ‘This one’s a new one, all you Liverpool groups, notebooks out!’”

The opening of Eric’s was a defining moment for Pete Wylie, too. “On 4 October I was about to start the University of Liverpool. That was the Monday. The Friday before that Eric’s opened and everything changed. I met people like Paul Rutherford, Holly Johnson, Ian McCulloch, Bill Drummond, then Julian Cope later. We were just seeing band after band after band, with Roger Eagle playing music you never knew existed, we would just go as much as we could. The breakthrough gig was The Clash in 77. Everyone was there tried to form a band, and 26 or 27 of us actually became successful!”

“The gig I remember most was Joy Division,” says Sergeant. “Nobody was really watching them. There was a front bit with the bar and we’d sit there and talk about shit and the Velvet Underground, but I was watching Joy Division. I went out to the others and said ‘You’ve got to come in here’, they were new on the scene and nobody had heard of them. That was a bit of a moment. It was just ‘Jesus, this is great!’ They’d kicked the doors right open. It led me down alleyways to Pere Ubu, Wire and Television.” Not every gig was so formative – “We hated the fucking Police, they looked old and they’d dyed their hair blonde to get in on the punk scene” – but as Sergeant points out it was the venue, not the bands, that was the destination. People used to go to Eric’s because it was Eric’s, it was somewhere to go. We’d go three times a week. It helped not having to pay to enter, if you were in a band they’d just let you in.”

Before long Mathew Street was alive with boundary-pushing creatives of its own, intersecting and converging at Armadillo, being educated at Probe then inspired at Eric’s. When Gayna Rose Madder, then an art student, began to start her own ventures into the music scene in 1979 she found it teeming with life. “I think it was on a parallel with London and nowhere else at that time, absolutely definitely not Manchester!” she says. “We’d go there sometimes and it just didn’t have anything like the same vibe or the same number of venues. I had a free pass for Eric’s at one stage, and every night they had something on. We started out against the background of people like Teardrop Explodes and Wah! Heat and The Bunnymen, and we just totally took it for granted.

“I used to put a night on in Eric’s for students and Monday night was the only one they’d give me, every single other one was booked. The very first gig we ever did was with Dalek I Love You which was Dave Balfe’s band, I’ve still got the poster we illegally printed in college. They started off by shooting peas through a straw at the crowd and I was thinking, ‘Oh my god, what have I done?’ But we became part of what you didn’t realise at the time was going to be an absolutely massive thing. You took it for granted that you knew these people. Everyone mixed and matched and ended up doing stuff with other people who were around. I was involved in putting on so many things at the time but that one was significant because it was Eric’s, and Eric’s was the centre of everything.”

There might not have been a Tony Wilson to tidy up and package the Liverpool music scene for nostalgic consumption, but young creatives had the sage guidance of Eric’s Roger Eagle and Probe’s Geoff Davis. “Roger and Geoff were pulling the strings really,” Wylie says. “Geoff was more than a retailer, he was a guru. Roger was a human totem pole, huge and dominating and he knew everything about music.”

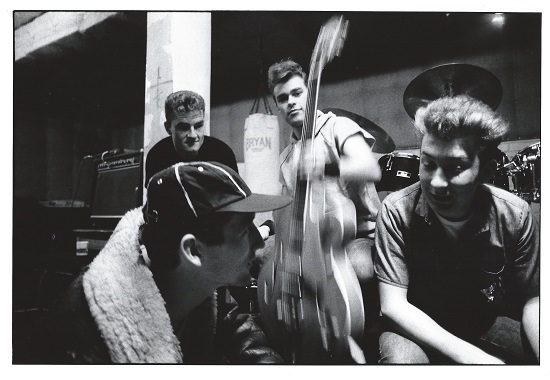

The DaVincis, photo courtesy of Christopher Stevens

It helped, of course, that the artists Liverpool was producing at that time were an expressive bunch in their own right – ‘We were bubbling away and ready to go, they just heated up the Bunsen burner!’ as Wylie puts it. In terms of venues, Sergeant points out, “Everywhere had somewhere, but I just think there were such big characters in Liverpool. People like Jayne Casey and Pete Burns, completely out-there people. Them, Holly Johnson, Paul Rutherford, were Eric’s royalty. We thought we were mad for having a few badges or a few studs on our jackets, they were really pushing it out. I remember Holly had his social security number dyed into his hair! There was a band called Dead Trout, they were my favourites. They were avant garde, like the Residents, fairly wacky and stupid. I can’t remember if the music was any good but they used to play with bananas. It was just ace to see a guy play the drums with a pair of bananas that just went all mushy.”

The essence of Liverpudlian music at this time thrived on the DIY ethos – Bill Drummond and David Balfe’s Zoo Records for example. This was a spirit inspired and defined by the state of the city itself, suffering as local industry began to die. Jayne Casey explains: “The interesting thing about Liverpool is that for a small city it’s got a massive history of bohemia. Normally you only get that in major cities like Paris or New York, but Liverpool’s got it too. When everybody’s got no money, families for generation after generation have lost the docks and you’re second generation unemployed you’re in this no-man’s land waiting for industry and society to recreate itself. It’s not that there’s no hope because you didn’t ever wanna go work down the docks or in the factories, so we were that generation who were saying ‘fuck off, we don’t wanna work down the docks!’ In some working-class areas that fall into desperate poverty there isn’t that same tradition of turning towards creativity, but in Liverpool people’s self-expression became really, really important. It was all you had left! Those kinds of circumstances really breed invention, the creative scene has to really pull together to make things work.”

Few if any of the artists of this time had much in the way of wealth, and those with jobs would spend their money on records from Probe or clothes from vintage markets (or, in Pete Burns’ case, Vivienne Westwood). However none of those tQ interviewed for this feature paid poverty much mind. “We were completely skint but you didn’t really notice,” says Wylie. I could sign on when I wasn’t using my university grant and do little jobs in Eric’s, people found a way. Roger and Geoff were aware of that, they wanted to subsidise our musical education.”

“You’ve got four quid in your pocket and you’re made up!” Sergeant adds. “It was just all about going to Eric’s, it didn’t matter if you had money or not as you’d get in for nothing, watch the bands and that was it. It wasn’t really a thing that we thought about, we weren’t doing it to get money we were doing it because I was interested in the artistic lifestyle of being in a band, trying to be one of the gang, trying to be cool.”

A Formal Sigh, photo courtesy of Gayna Rose Madder

And then, on Friday March 14, 1980, Eric’s was raided by the police and shut its doors for good. Wylie’s Wah! Heat were performing that night, in support of The Psychedelic Furs, with McKechnie, Madder, Casey and Sergeant all among the audience. It was ostensibly a drug bust, although such justification rings pretty hollow to any who regularly attended the club. As Madder tells it: “There was absolutely no reason for it, and no reason was ever given. The police kept saying they suspected there were drugs in there, but I never saw any drugs in there, never, while at several other clubs you’d be offered them before you got through the door! The police didn’t like the alternative way people dressed, I think they were very, very prejudiced. There would inevitably be a queue outside Eric’s if there was a big-name band on, and people would have various costumes on, they’d look gothy or weird, or have strange hairstyles or clothes, and I think [the police] were just looking for a reason. People were getting away with murdering people in the Seel Street Clubs where you were required to wear a suit to go in, but with this one they just had it in for us.”

Joe McKechnie and his girlfriend were already on their way out and were the first to see the police, plain-clothed but armed with batons, arrive as they exited the venue. They were thrown against the walls and searched to the extent that a friend had to remove a plaster from his bare foot to prove he had nothing to hide. Sergeant, meanwhile, was still downstairs: “The Psychedelic Furs were playing – it was before we knew they were shit – then all of a sudden a load of coppers were in there, plain clothes blokes who you knew were coppers because they had coats on to keep them warm before they pounced on someone. I put my hands up against the wall like in those American films and he said ‘Alright there, soft lad?’ and punched me in the stomach! I guess you were allowed to do that in them days!”

It was a shock, but one that many had seen coming as Eric’s financial viability became more and more unstable. “Roger became reckless, determined to keep going until he burned out,” says Wylie. “He kept putting gigs on even when they couldn’t afford to. I was saying during the gig ‘It’s gonna close, it’s gonna close! You’ll never see another Liverpool band here again!’” Protest marches took place through the city in response and the club reopened as Brady’s under new management, but things would never be the same. “Brady’s was run by people who were not of the music community,” Wylie says. “I don’t want to say too much but every time Brady’s opened you’d hear the theme from The Godfather…”

Eric’s had died, and for many the heart had been ripped out of the Liverpool scene, yet in many ways its mission had been completed. By 1980 its progeny had begun to diversify, and to spread outwards from the Mathew Street nucleus. A club named the Warehouse took up the mantle for indie bands both big name and local (before burning down in what McKechnie calls “mysterious circumstances”,) while other less conventional venues started jumping on the bandwagon. “One of the strangest ones was a pub on Duke Street called The Monro,” says McKechnie. “It was run by a Chinese fella called Ernie Woo. The Arena Studios were next door and they had a basement where the Bunnymen were rehearsing at the time. In their breaks they’d go into the nearest pub so they got to know Ernie. Next thing we knew the Bunnymen were doing a secret gig behind the bar! I foolishly went home to get changed and by the time I got back Duke Street had been closed off by the police because there were so many people trying to get in! Off the back of that the back room of the pub became a central gig venue for a while for anyone who was playing. Things like that happened all the time. Ernie Woo was in his sixties, and it was him facilitating all this. Things like that would happen all the time.”

The quality of the music was intensifying too, evolving from the scrappier, occasionally naive sensibilities of the early Eric’s years as line-ups began to solidify and singles started denting the charts. “All your mates were suddenly becoming successful!” Casey says. “The Bunnymen were doing stuff, the Frankies were doing stuff, that period was a great time for the city. Eric’s was the time of your life but then looking back I really loved the 80s. Because Liverpool was in quite steep economic decline we had loads of space, which is kind of what you need to make things happen. It became a really, really creative time.”

Ellery Bop, photo courtesy of Jamie Farrell

The latter stages of the decade saw the dawn of the annual Earthbeat Festival in the city’s Sefton Park, an annual celebration of music both homegrown and further flung under the stewardship of the much-admired artist, activist and promoter Kif Higgins. Free to the public and taking place across four days over the bank holiday weekend it was a marker of how far the city’s once-underground music scene had rocketed to mainstream adulation. “It brought a lot of people to the fore, it was a really major event,” remembers Madder, who was among the performers as a solo artist. “Kif Higgins was an amazing guy, he had a real good overview on what was happening.”

“It was forward thinking and eclectic,” adds McKechnie. “It brought in electronic music and DJs alongside bands like The La’s and Frankie Goes To Hollywood.”

Politically, however, Merseyside was in turmoil throughout the decade, with an ultra-hard left city council’s war against the Tory government intensified following the Toxteth riots of 1981. Musicians increasingly began to engage with their home’s tumultuous landscape, prompting a marked concentration in their work, most notably in the form of Public Disgrace’s vicious punk lambast, ‘Toxteth’. “When Thatcher started really gunning for people, it did get worse after that. I was right in the middle of those riots in 1981,” remembers Madder. “They really did change everything. They took place in an area that had a lot of late night venues, and it did alter things. I think people started writing differently after that, and [the riots] could have been a trigger to people looking towards bigger companies to get some money; the scene couldn’t be as local any more. It still wasn’t difficult to perform, but It was difficult to get paid, the amount of money you could get from performing was shrinking.”

It is important to note that even from its earliest days, the Eric’s scene and what followed was by no means a harmonic utopia. It was marked from the very outset by bitterness, squabbling and feuds. As part of one of the first bands to make an impact, Big In Japan, Jayne Casey was often on the receiving end. “By today’s standards a lot of them went too far,” she says. “Bands like the Bunnymen and the Teardrops formed later on so at the beginning we were the band, we had the focus, all those musicians who wanted the stage were focused on destroying me and destroying us.” A short-lived band The Nova Mob, containing one Julian Cope, were described by rock historian Pete Frame in his extraordinary ‘Family Tree’ of the Eric’s progeny as ‘more of an anti-Big In Japan lobby than a group’, printing anti-Casey t-shirts with her face on and circulating a 1000-signature petition for the band to split up.

“Later on the rivalry became The Bunnymen vs The Teardrops, then there was Burns versus Frankie, but to begin with a lot of it was against me. I was the only girl and I was hogging the stage!” Casey continues, alluding to the fact that much of this was undeniably motivated by sexism. “I had to be pretty tough – my contemporaries were Pete Wylie, Ian McCulloch, Holly Johnson and Bill Drummond! I had to hold my own, and I was a pretty tough little cookie. A lot of those names I’ve just mentioned later wrote me letters apologising, I took a lot of stick, like. It wasn’t right on, it was hard going.”

Madder, too, encountered her fair share of hindrances at the hands of the patriarchy. “No disrespect to them at all, but a lot of the bands that made it big had very, very good managers, and it was really difficult to get management unless you had a load of strong males with you. I remember going to a meeting about a concert. It was my band completely, it was called the Gayna Rose Madder band, but the promoter kept speaking to my boyfriend instead. I was trying to butt in and say ‘What we need is this’ and he would just turn round to me and say ‘Alright, curly!’ because I had curly hair back then and refer straight back to my boyfriend. That was in 1987, it was an attitude that was around a lot back then.”

The Revolutionary Spirit box set does much to realign the balance of just how many people contributed to the movement in addition to the household names, it gives as full a picture as has ever been painted of just how diverse and multi-faceted the artists operating really were. No one band is like another across its 100 songs, a reflection of an almost dogmatic determination not to copy one another. Some of this was down to the aforementioned petty rivalries, but as Casey points out there was a more overbearing influence. “Liverpool tends to diversify musically because it’s trying to avoid a cliché that it created, that’s the simplest way I could put it,” she says. “Roger Eagle called me, Ian McCulloch and Pete Wylie into the office for a meeting one day, and he never called meetings. He told us we had to not listen to The Beatles, and that if we listened to them it was all over. Only a couple of years ago I was sat having a drink with Ian McCulloch and Pete Wylie, and Pete looked at me and said ‘I reckon she pressed play you know, what d’you reckon, Mac?’ And I fucking haven’t! I never pressed play! I looked back at him and said ‘I know you pressed play, I can tell by your music!’, not once was ‘play what’ mentioned, it was code language between us.”

The Onset, photo courtesy of Mike Badger

“We needed to put a line in the sand,” says Wylie. “Without that line The La’s would have been seen as a sub-Merseybeat band, but because of it they got to be seen for what they are, in a beautiful unique light. We’re not knocking the shadow, we’re just next to it!”

Among the liner notes of Revolutionary Spirit, Liverpool DJ Bernie Connor describes this period as “A purple patch to put any other period the city had to offer in the shade”, and in many ways he is correct. The music of that day may have been too fragmented and divergent, too off-kilter, leftfield and forward-thinking to be packaged in the way Merseybeat has been, but in 2018 it holds a power that eclipses what came out of that other Mathew Street club, The Cavern. The Magical Mystery Tour and The Beatles Experience might still be a thriving tourist trade, but for the city’s current breed of musicians it is the lessons of Deaf School, Big In Japan and The Crucial Three that hold court. “If shit’s not happening, do it yourself, set up the record label, set up the bars and clubs and venues,” says Jayne Casey, still a major figure in the city’s Baltic Creative sector today. “When I see the independent sector thriving I see the roots from which it started, I see its roots in Mathew Street. I think that is separating Liverpool from some cities, the independent sector is so buoyant.”

As we approach the end of our interview, Pete Wylie still has much to say. “I have to go in a minute, but I’ll leave you with this,” he proclaims with his eye on a grand finale. “Every interview I did back then was about The Beatles. I would always be written about as ‘Pete Wylie, from the home of The Beatles.’ But I’m not from the home of The Beatles. I’m from the home of Wah! Heat! I’m from the home of Eric’s!”

Revolutionary Spirit: The Sound of Liverpool 1976-1988 is out now on Cherry Red Records. You can purchase it here.

Thanks to all those who agreed to be interviewed for this feature, and to Matt Ingham at Cherry Red for his assistance in tracking them down.