As Yeye Taiwo Lijadu stood at the funeral for her identical twin sister Kehinde, she felt her mother’s words rise up in her: “You are not a star.” Yeye Taiwo repeated these words out loud to her sister. Shock filled the room as other mourners queried why Yeye Taiwo would disparage her sister after being so close to her for so many years.

Yeye Taiwo later explained that the she was repeating her mother’s plea to the twins many years before, as they were entering the public eye in their home country of Nigeria. She wanted them to follow their own artistic path and to avoid fame and the perils that come with it. As Yeye Taiwo recalls the moment today, speaking once again to her sister, she says softly: “Stars fall, you did not fall. You did all your duties. You did everything that you had to do in life. You are not a star because you are the sun and the moon, and they don’t fall.”

The twins may not have seen themselves as stars (others may beg to differ), but considering the lasting impact of their work, and their mother’s insistence they were meant for something more profound than fame, these words ring true. Together Kehinde and Yeye Taiwo were the legendary Nigerian Afrobeat group, The Lijadu Sisters, and were among the few female pioneers of the Nigerian pop revolution during the early days of the nation’s independence.

Over five albums released between 1969 and 1979, the twins wrote and recorded songs that bravely spoke to the political corruption in Nigeria, dealt with women’s rights at a time and place when this was a controversial subject, and dealt deftly with the personal as political field of relationships. Their musical palette was expansive, utilising Afrobeat, disco, reggae, soul, funk, and psychedelic rock, over which the sisters sang together in Yoruba, Igbo, or English, always in close harmony or in unison.

Their unity was key. The driving force behind these inventive, Afro-pop anthems was the relationship between the sisters who were so close that the terms sisters seems slightly insufficient to describe their bond. They barely spent more than a few days apart before Kehinde’s death, they dressed identically, regularly finished each other’s sentences, and raised their children together. They were soul mates as well as siblings.

After a serious fall down the stairs in the 1980s, Kehinde suffered long term health issues that left her bed bound, putting the sisters’ career on hold. Yeye Taiwo nursed her sister for years and after Kehinde regained some of her strength they were able to play occasional shows but never recorded another album.

Sadly, Kehinde passed away in 2019, a loss that is impossible for Yeye Taiwo to measure. Grieving, she left their shared Harlem apartment to stay with a cousin in Brooklyn, unable to step back into the space where they had made a life together. But after four months she decided it was time to go back home, telling her cousin she was ok, even though she knew she wasn’t. “I didn’t know where I was. I was just like a ghost. Three quarters of me was gone.”

The Lijadu Sisters popularity, both in Nigeria and later overseas, helped the group connect with a swathe of wildly different artists, including hip hop legend Nas; emo pop’s golden girl and Paramore leader Hayley Williams; and art rock polymath David Byrne, who brought the twins on tour to celebrate the work of the Nigerian artist William Onyeabor.

Despite the respect many artists have for them, for decades the sisters had little control over their back catalogue, leading to numerous problems with copyright infringement, unpaid royalties, and label disagreements. “You became used to it, but then would think, ‘Okay, I’m alive, I’m going to correct all of that’,” reflects Yeye Taiwo. “It leaves a very bitter taste in your mouth, but then how long are you going to retain that bitterness?”

It was only after Yeye Taiwo was able to gain control of their recordings in 2021 that a plan could be put in place to reassert the legacy of The Lijadu Sisters. Working with the label Numero Group, The Lijadu Sisters will re-release their entire back catalogue, starting with their final record, 1979’s Horizon Unlimited. It is a record that best demonstrates the sisters’ unique vision and their crossover appeal in the West, smoothly incorporating buoyant funk rhythms with the rubbery beat of the traditional talking drum and the sisters’ bright harmonies, heard on songs like the joyously addictive ‘Come On Home’.

After years spent as the quiet favourites of music aficionados, Yeye Taiwo is happy The Lijadu Sisters are finally able to reach a new generation, but confesses, “I wish it had happened when my sister was here.” She sighs, adding: “I do miss her a lot.”

Speaking to Yeye Taiwo over video call from her Harlem apartment, it is easy to see mementoes of her life with Kehinde adorning every visible surface. Bright purple fabrics drape across the ceiling, crystals and candles are dotted on everywhere, illuminating pictures of the twins with celebrities they knew such as Issac Hayes.

The twins moved to the apartment 17 years ago, in 1988, after making the US their home. They originally came to the States on tour with Nigerian juju legend King Sunny Adé, and stayed after claiming political asylum. Despite living in America for so long, Taiwo is quick to correct the idea that they moved there. “We did not move to America. People keep saying that,” she says firmly, suggesting that their hand was forced. “A lot happened to us. Our passports were stolen. It was difficult to get new passports even though we were going to the Nigerian embassy. Who would choose to leave their country of origin and go and stay somewhere else?”

Throughout our conversation Yeye Taiwo is as direct and endearing, laughing heartily and infectiously. Now in her mid-seventies, she speaks slowly, pausing every few seconds with the cadence of an elder imparting words of wisdom. The twins spent years working as spiritual healers, and today Yeye Taiwo is continuing that mission, having travelled to the Republic of Benin to complete her priesthood and became a chief (a process through which she gained the title Yeye). While in Benin, she had the chance to visit the house of her great grandfather who was a slave master. It was a emotional but necessary experience. “I went to beg the spirits and souls of those people who were sold,” she says with wearily elongated words, “I went to beg them for forgiveness.”

Born in Jos, Nigeria, on 22 October, 1948 and then raised in Ibadan, the name Taiwo translates as “the first twin to taste the world”, while Kehinde literally means “the second-born of twins” or “chaperone”. They were encouraged by their mother to sing and write songs from an early age and she introduced them to music by Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Miriam Makeba and Nat King Cole. “She was kind, understanding, and very respectful of everybody around her, including us, her children,” says Yeye Taiwo. Adhering to their mother’s advice to always write songs that people can relate to, the sisters worked diligently on their music.

After releasing their first single in 1969, a cover of Miriam Makeba’s ‘Jikele Maweni’, the sisters released their debut album Urede in 1974, featuring all their own compositions, followed by the moody funk of Danger in 1976, which featured ‘Life’s Gone Down Low‘. The found further success with 1977’s Mother Africa which, as the title suggests, featured a reinvigorated Afro-centric direction. They continued to expand their musical reference points to take in synth pop and punk funk on Sunshine (1978) and Horizon Unlimited (1979), working in disco, funk, and reggae rhythms.

The sisters wrote and arranged all of their songs, sometimes taking advice from their mother or their children on what to include. Since they never formally studied music, they came up with their own method of composing and teaching their songs to the session musicians in their band. “We would sing the part to them in Yoruba,” she explains. “The drum part, the guitars, the horn parts, everything was sung by mouth, and they would be like, ‘Huh!’ They understood what we needed through that medium.”

Outside of their compositions realised on these albums, Yeye Taiwo is certain the real magic to be found in those studio recordings was due to the food the sisters cooked up every day for their band. “That’s why the records sound the way they sound”, exclaims Yeye Taiwo. “Because if you feed people good food, cooked from the heart with love, they feel it and they will respond likewise.”

The sisters were the female leaders of an all-male band, a feat that was especially difficult in a music industry and country that was at that time suffocatingly patriarchal. “Women were judged to have no place anywhere but the kitchen,” says Yeye Taiwo. “You’re looking for a job, but they want to have sex.” Though some men were dismissive of them early on, by the time they started recording attitudes began to change; because they were known for treating and paying their musicians well, everyone wanted to record with them. “We spoke with them like they were our fathers, our brothers, our husbands,” she says. “We accorded them respect so they now looked at us like, ‘Why are we afraid of them?’”

As much as they mothered and fed their band, they also knew how to keep them in line. “We did not take nonsense from anybody, we did not give nonsense,” she states firmly, adding that Kehinde was the one that the musicians had to look out for. “Have you ever seen where the lightning goes [she screams loudly] just like that? Don’t play with her. No, she was the firebrand. I was the cooler they could drink water from, [I came from the] opposite direction.”

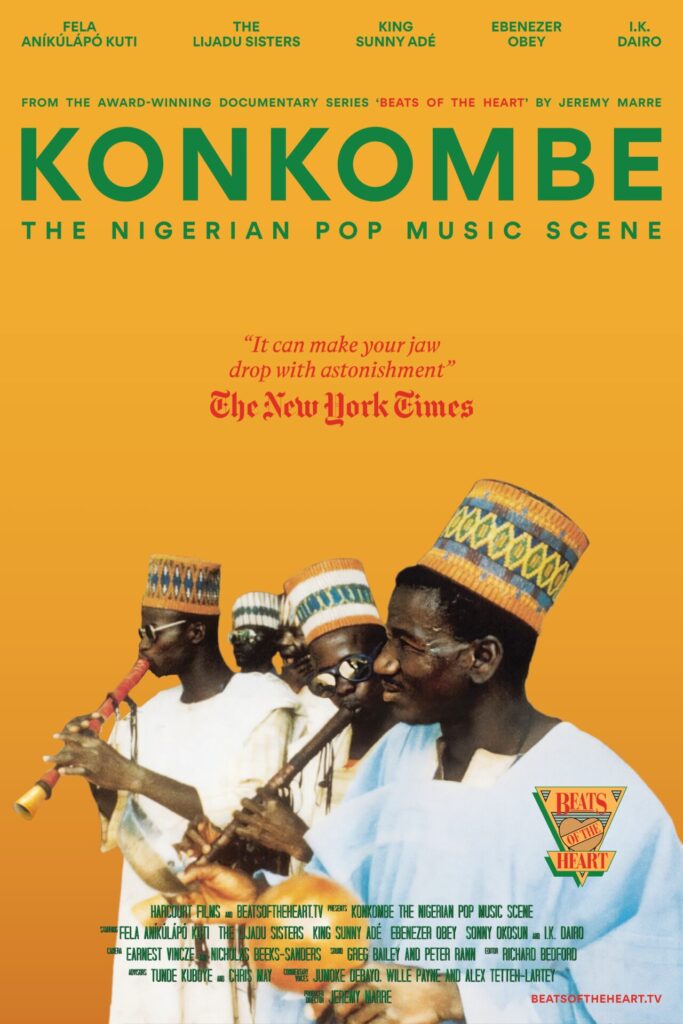

In the 1979 documentary on the Nigerian pop music scene Konkombe, which is being screened at select cinemas this autumn, the sisters were described as part of a new generation of liberated Nigerian women. The twins are quoted then as saying, “women are now telling their men they no longer want to stick at home and live a dull life”. Their confidence and fierce independence unsurprisingly aligns to viewers today with a feminist perspective, but for Yeye Taiwo the word has little meaning. “What do they say about men who fight for people’s rights? Are they macho?” she questions. “Why feminist? Why not somebody who is fighting for her right and the right of women to live normally?”

Whether or not that fight has to be given a name, The Lijadu Sisters did fiercely speak out for women’s rights as well as the rights of the everyday civilians around them. Like many in the country at the time, the sisters were radicalised watching the political turmoil that was erupting all around them and wrote songs decrying the misuse of power, while advocating for change.

Songs like ‘Orere-Eleligbo’ were written to help put the power back in people’s hands, full of declamatory warnings: “Get Out! Fight! Trouble in the streets!”; while ‘Life Gone Down Low’ is a plea to a lover acting metaphorically as a call for nuclear disarmament. But bold political statements like these put the sisters in danger and made them an enemy of those in power. “[Military police] came to the house harassing us. ‘Which political party are you rooting for? Who sent you to sing those songs? Are you out of your mind?’” Yeye Taiwo nods to their determination: “We were writing and releasing [serious] songs before the advent of the soldiers, before people knew us.”

The Lijadu Sisters were not the only artists in Nigeria, who spoke out. One of the godfathers of Afrobeat and Nigeria’s most famous son Fela Kuti, who was the second cousin of the twins, was a major, iconoclastic figure due to his unapologetic pan-African, anti-colonial ideology. Though she is not shy to admit she has both “good and not so good” memories of Fela, whose opinions on women jar with the more enlightened standards we take for granted today, Taiwo still recognises his importance. “Sometimes I still don’t believe he is dead,” she says, “neither of us wanted him to die because of what he means – not just to Nigeria or the Yoruba as a race – but to everyone. Fela is the heartbeat of the world.”

The revolution Fela incited, both culturally and politically, inspired musicians from around the world. One of the first European musicians to come to Nigeria was legendary rock drummer Ginger Baker, who also briefly dated Yeye Taiwo and was the object of The Lijadu Sisters love song ‘Danger’. When I ask about Baker, Taiwo smiles, remembering Baker as a “unique musician” and “a different character, totally misunderstood”.

The reason why he was misunderstood would become clear to the sisters when they discovered Baker’s heavy drug use. They were due to go on tour to Europe and America with Baker, but were unsure after learning about his addiction to heroin. It took a call from their mother to Baker to straighten things out. “She said, ‘Ginger, sit down let’s talk. You’re taking my daughters on tour with you. They are not drug users, please don’t introduce drugs to them. Bring them back home to me whole’.” The call, along with three church services praying for the sisters, did the trick and the tour went ahead without a hitch.

There are so many stories that make up the narrative of the Lijadu Sisters’ life. As the keeper of their legacy now, Yeye Taiwo is proud of many of their achievements, but hones in on their part in breaking the glass ceiling for women in the music industry. “There are women who are rich in show business in Nigeria. I’m glad we were an influence on that”. It is true that some of the biggest stars to emerge from the Nigerian pop and Afrobeats scene today are female artists like Tems, Ayra Starr, and Tiwa Savage, who would likely not be where they are today without the giant strides forward made during the seventies.

Today, Yeye Taiwo is ready to do what she can to keep the memory of The Lijadu Sisters alive. She has been spending her time interacting with fans on Facebook who have gone on to introduce the music to their own children and grandchildren. She talks to them about the idea of returning to playing live music after such a long break. “People ask, ‘What are you going to do? You haven’t been on stage for so long to do this.’ Am I dead? No,” she snaps, once again displaying the steadfast spirit that kept her and her sister going, “As long as you’re alive you can feel the heartbeat of the world, the people, you know what’s going on with them.”

Horizon Unlimited is reissued this week by Numero, with other Lijadu Sisters albums to follow. Konkombe will be screened in London, various American cities and Nigeria this Autumn