In pop music, and the cottage industry set up to auto-mythologise it, there’s little premium higher than the small coterie of bands whose skimpy discographies are inverse to their XXL influence – Sex Pistols, Joy Division, Young Marble Giants, Slint, Television. You’ll notice that all of the above are indie or alternative acts. Unless from early death, you’ll find little of this mythologising in soul or in jazz. What can we learn from this? The early split being the logical end point of indie’s cult of detachment?

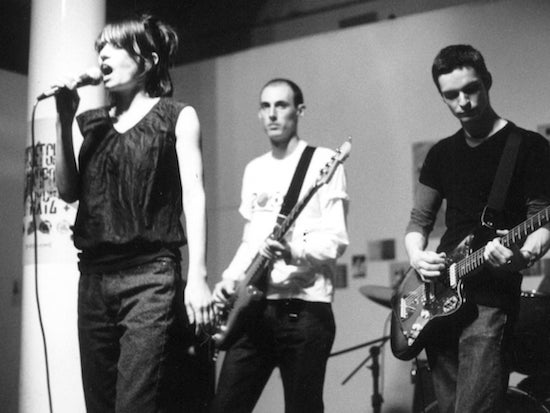

Life Without Buildings, from Glasgow, split with little fanfare at the end of 2002. Their end came amidst the false dawn of NME’s New Rock Revolution, the last serious goldrush on British guitar music – perhaps forever. But where much of that music only withers with time, something about Life Without Buildings has gone on to endure. Though utterly Marmite at the time, their template – sprechgesang vocals with free associating lyrics, often cribbing from pop culture, against wiry post-punk – has become the default mode of a certain type of British band. And then new technology would arrive to allow their music to spread in the most unlikely of ways. Life Without Buildings sidestepped only very briefly from the art world to the music industry, and back into the art world again for good.

By 1999, it was hard for the 28 year old artist Sue Tompkins to describe exactly what it was she did. “I was a late developer, I think, in some ways” explains Tompkins, “If I met someone new I would find it very hard to say that I’m an artist, or I’m a painter or a poet or a musician. I knew underneath that I was hopefully a bit of all of those things." Words had become increasingly central to Tompkins’ practice since her graduation from Glasgow School Of Art a few years previously – words typed on pages, hung on walls, hours of words spoken into Dictaphones and played back in galleries.

The artist David Shrigley was a contemporary of Tompkins, and played in bands that would involve future Life Without Buildings members. “Sue was a White Cube type performance artist” he remembers, “there’d be an exhibition and she’d do a performance in the gallery space. The performances were very singular, very unique and very consistent with her personality.” Tompkins was part of the Elizabeth Go collective, alongside her sister Hayley Tompkins, Victoria Marton, Sarah Tripp and Cathy Wilkes, a loose group of artists operating in different practices.

Meanwhile, another group of visual artists had been joining forces for something entirely different. There are times when cities breathe in and breath out, and the launch of the highly influential Optimo club night in 1997 started what seemed like a giant inhalation. People who might normally have formed bands instead went out raving, reconsidered their musical allegiances and had wide-eyed after hours conversations about art and music. Will Bradley, Chris Evans and Robert Johnston were all practicing artists, all Optimo heads, and had been tentatively trying to form an electronic group inspired by their mutual passion for Underground Resistance, New Order and Missy Elliot.

“Optimo was a really big thing for everybody” says guitarist Johnston, "it synthesized dance music within rock, and that was our thing, that was what we were interested in. I’d got into Disco Inferno and sampling, I thought we were going to be that sort of band." The problem is, it didn’t really work. “Nothing felt right unless we played it live with guitar, bass and drums” says drummer Will Bradley, “so we learnt to play better, and play the music they way we wanted it to sound.”

The band badly needed a fourth ingredient. The three friends arrived at Glasgow’s artist led exhibition space Transmission for an Elizabeth Go exhibition – they all knew Tompkins to varying degrees – and watching her give an amplified spoken performance at the space, they were all struck by the same idea.

“I was really blown away by that performance, I was really impressed” says Evans, "there was a conversation afterwards that we had to invite her to one of our rehearsals, and then she brought her writing with her. It was as natural as that really.”

Tompkins had never had any ambitions to join a band. “I think as an artist, I think you’ve got to do stuff and it’s so good to do things” she explains, "just that thing of not pre-empting things too much. So I had no honest real idea why I would say yes to do that.”

When Tompkins joined the first rehearsal, she remembers hearing the three-piece grindingly repeating the same few songs, often repeating the same phrases from songs to piledrive them into order. “I didn’t put much pressure on myself but I do remember thinking, ‘Ooh, it’s about time I did something now’ after about 45 minutes of looking at my notes, and them rehearsing the same chords” says Tompkins, “I’d sing things in my head at first, and then when I had the confidence I’d just do it. A little bit of fear, a little bit of everything, nothing to lose.”

Rehearsals quickly began to work. Within a few sessions, the band had written what would become their most enduring, most celebrated track – ‘The Leanover’. Autumnal and pensive, ‘The Leanover’ bridges the gap between Slint and the Smiths.

Listen to the way that the three-piece rise and then fall, rise and then fall, Robert Johnston’s mathy arpeggiations bridging the gap gorgeously between Louisville and Manchester. A gorgeous piece in anyone’s hands, but transformed by Tompkins – whose scat vocal introduces the track, at first unaccompanied – alchemising it into one of the most interesting British guitar records of the 21st century thus far. Tompkins’ words throb with memory and loss – “days like television”, “I don’t change”, “sweet remembered contact.“ It resists becoming anthemic. Like ‘Virginia Plain’, which is referenced in the song alongside a line from Robert Wyatt’s ‘Sea Song’, it has no chorus.

They’d been hammering the piece out in rehearsals without really being able to hear Tompkins’ vocal at all – this would change in Johnston’s bedroom when they recorded her vocal track for the demo. “It was one of those moments where there was complete silence after it” says Johnston, "that’s it, that’s the thing. It sounded completely new, we were aware that what we’d been doing [previously] was quite… derivative.”

The singularity of Tompkins’ vocal performances began to inform the music itself. “I was entranced by the way she could just shift the register to really broad ranges, taking you on a journey with it” says bassist Evans, “it meant there were things we could anticipate. We could do a provocation, to avoid it slipping into something straightforward. It meant there was something for us to play off against, or for Sue to play off against.”

“My friend Natasha let the nascent Life Without Buildings rehearse in her bedroom” remembers the artist Toby Paterson, “but I’ve got memories of them rehearsing ‘The Leanover’ behind that closed door and thinking it sounded quite interesting. It was obviously coming together in a really organic way. You’re used to years of being polite about pal’s bands, and here’s this one that’s actually kind of captured something of the moment.”

The band booked their first show at the Hope & Anchor in Islington – a bold statement of the band’s intent to avoid being simply a navel-gazing concern for Glasgow artists. “At that time there was a lot of art bands happening" explains Johnston, "Big Bottom, Martin Creed. A lot of artists had bands and were very self consciously art projects. We didn’t want to do that. It’s a bit disrespectful to music, the art band thing didn’t seem like music fans for us, it was like they were in it for ulterior reasons.

There was an aloofness from the music there.”

Someone who caught that London show was Glen Johnson, a musician in ambient pop band Piano Magic as well as a visual artist and, at that time, running Tugboat Records – a subsidiary of Rough Trade. Impressed by what he had seen, Johnson took the demo of ‘The Leanover’ – which had now been joined by another track, the fizzing motorik ‘New Town’ – up to Geoff Travis and Jeanette Lee at Rough Trade.

Travis remembers the instant approval with which the Leanover demo was met in the Rough Trade office. “It was so different and so fresh” remembers Travis, “all the people in the Rough Trade West shop just went mental for the album. Sue is such a brilliant front person, there wasn’t anyone like her ever really. She’s a real original that woman." Warp Records were interested – who were not yet making a habit of signing guitar acts – but Rough Trade prevailed.

Andy Miller very nearly never produced Any Other City. The man who all of the group credit with seriously realising their vision was putting his jacket on to leave Glasgow’s Chem19 studio when the band eventually turned up, ninety minutes late. “They were all such great people” says Miller, “we just got on like a house on fire.” It was Tompkins’ first time in the studio, and Miller instinctively got what was special about the band and its vocalist. The record’s serious physicality would be the result of a philosophy Miller describes as “play through the pain barrier” – often literally, with several late night sessions resulting in hand injuries. Miller learnt how to do First Aid recording Any Other City. The fine art graduates enjoyed using conceptual ideas to break studio impasses. Something wasn’t quite right with ‘The Leanover’, before Will Bradley began speaking in increasingly abstract terms to Miller, asking him to picture “amber light radiating from a central core, surrounded by a shower of blue sparks”. “And then it just clicked right away” remembers Miller.

When the producer was ill for two days, the band stayed in the studio and wrote the terrific power pop of ‘14 Days’ – its riff a lovely inverse of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Let’s Spend The Night Together’ – alongside ‘Sorrow’, which would close the album. One of the most affecting tracks on the record, ‘Sorrow’ shows Tompkins’ ability to apply her writing method to increasingly wintry, solitary moods.

“The take of ‘Sorrow’, that was the first time we’d ever played it” says Robert Johnston, “Sue’s amazing on it. It was written in the rehearsal room next to the studio, so we just went straight into the studio, that recording was the first time we’d played it right through – we wouldn’t have done stuff like that on a second album because we’d have known better.” When the final mix was completed, they celebrated first with champagne, then with Buckfast.

What Miller understood was that Sue Tompkins was an incredibly special vocal and lyrical performer, and that the success of the record would depend on how well conveyed that was. “I was trying to make sure the lyrics just caught you” says Miller, “I absolutely love her lyrics. Just so energetic, so uplifting.”

Viewed with twenty years’ distance, it’s the fragmented, modernist element of Tompkins’ writing that continues to dazzle. It’s the enigma that repeat listens cannot dim. Some words are picked for their meaning, some words simply for how they sound – it’s up to us as listeners to consider the difference. Tompkins brings in metatextual references, reeling off pop cultural found objects like the aforementioned Virginia Plain and Sea Song quotes, but also Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way, the Fun Boy Three single ‘Our Lips Are Sealed’, or repeating the abbreviation of My Bloody Valentine multiple times. This has endured throughout Tompkins’ later work, movingly quoting snatches from Chic’s ‘I Want Your Love’. It’s experimental in form but hugely generous in spirit.

“I have got a writing style” says Sue, “but I’m in denial of it, and being in denial of it is a way of keeping it going. Everything does mean a lot to me, and I try to write often with an attachment to a visual or emotional memory, which is so obvious, but that’s the way that I write. I write when I think I’m affected by something. I like thinking about collage, like a Rolodex of image and word, music, rhythm, repetition, and when it repeats you’ll see it differently, just those really delicate, interesting things. Looking back, forward, the present. I hope it resonated with people, I did want to communicate. Maybe the form can be quite fragmented but the actual words I’m saying, I always think they’re quite clear.”

On something like ‘New Town’, words and syllables are repeated staccato in the verses to ratchet up the tension, before giving release in the chorus with longer, more languid phrasing. Indeed, her vocal is a speeded up version of her band’s post rock obsession with dynamics. Unpleasant or anxious feelings are easy to convey in pop music, but the sense of wonder that comes from Tompkins’ rush of free associations is a rare and precious commodity, giving the illusion of improvisation. It comes as no surprise that her work would find appeal within hip hop – Frank Ocean picked ‘The Leanover’ as part of his 2018 Blonded mixtape.

Geoff Travis suggests that the only real precedent for her writing is Mark E Smith, not for the attitude and vocal tics that are most commonly lifted, but for the actual creative part, “the way he used language in this cut up and clever way, juxtaposing improbable images together, giving permission for people to write that way.”

Paul Thomson, then drummer for Glasgow band Pro Forma but soon to form Franz Ferdinand, caught an early show and quickly became enamoured. “What I like most about Sue’s words is that it’s almost like she’s taking the raw materials and disparate thought processes” says Thomson, "the disconnected thought processes that go into making lyrics, but instead she’s just thrown in the raw materials in a completely, seemingly random, way.”

Pro Forma would perform at the launch of Any Other City – Life Without Buildings were determined to avoid performing their own launch at 13th Note bar. “It wasn’t packed out, I saw them quite a few times and it was never that busy, for the people I was with it was a 50/50 split with those who couldn’t stand it, who found Sue’s vocal irritating. Some people I was with would actually heckle them, which was embarrassing.”

The album was released on 26 February 2001. The Guardian gave a positive three star review, Betty Clarke understanding some of what Tompkins was aiming at – "words are posed as questions, and repetition is key, a sentence spoken over and over until it leads to an unrelated idea". The band were particularly bruised by a two star NME review by Jon Mulvey, which though conceding that the idea “to invest post-rock with a lively shot of personality is actually rather noble… That Voice is enough to make even the staunchest apologists for cranky music reach for the morphine”, adding that “only mad people and immediate family could warm to Tompkins.”

“Shame on them” says Evans, “to really focus on the intonation and pitch, that was really grating, to say that a woman has to have a certain type of voice. That’s the crucial thing in this, right, what are the grounds for how a female singer should sound, and appear, and behave?”

“Music journalism then was still an old boy’s club down the pub” reflects Johnston, “the inkies were on their last legs, we were on this weird cusp of something in the music industry. You could still sort of sell records, but it felt like everyone knew it was going down the drain at the time. People on the web, though, wrote nice stuff, mostly female writers.”

“I think I’m a very thin skinned person, I’m sensitive and I take things quite seriously” says Tompkins, “there were a few things written but I never got too hooked up on that, I just thought, well that is what I did, I’m not trying to be anything that I’m not. I don’t quite know, but I managed to not get weighed down by that or lose confidence through that.”

“I remember reviews that were dismissive of Sue, and she’s just such a likeable person, such a sweet and genuine soul, that it felt just so unkind to say about her” says David Shrigley, “but that’s the thing, for Sue it was a project she was asked to do by her friends, indie rock was not her thing and she had no desire to do that.”

Events were flowing away from Life Without Buildings. Around the release of Any Other City, they supported the Strokes at Camden Monarch. Though fan legend would have it that the band were booked initially as headliners, there’s no evidence from the band for this, indeed the consensus being that they were simply lucky to get the slot at all.

“The Strokes orchestrated a bit of a fight outside on the corner so that NME had something to print” laughs Evans, “I found them a bit reactionary myself. It sounded like something to avoid to me. Didn’t they all go to elite finishing schools or something?"

That Strokes concert would mark the beginning of a music industry goldrush towards a certain type of guitar act – Life Without Buildings continued to tour, but Tompkins’ passion for the project was seriously waning.

"We only had twelve songs, it wasn’t as if there was any surplus” remembers Tompkins, “There’s this idea that musicians are prolific and always have something to pull out, but we didn’t really work like that.” She pauses. “It’s weird because I really liked it, but I don‘t think I wanted to do an American tour, which was the thing that was being talked about. It was just, ‘Oh, now I’m in a band, and I’m the girl in the band, I’m the singer being pushed to the front.’ Really basic stuff, but I just wanted to shut up a bit and let someone else come forward and none of them were happy with that, and I understand that as well. It’s a little pot of stuff that if we’d have talked about it a bit more clearly, we might have got through it and easily made a second album. I didn’t want to be at the front all of the time.”

“There was a gig in Bristol at a 750 capacity venue, and generously there was about fifteen people there” says , "we played underneath an enormous papier maché goose, as 15 teenagers just got off with each other in the corners.” During a tour supporting Belle and Sebastian, Sue was repeatedly heckled.

Though Life Without Buildings in total played no more than forty shows in their short lifespan, they did manage to perform in Greece and Australia, a minidisc soundboard recording of the latter becoming the excellent 2007 release Live At The Annandale Hotel. “There weren’t really many conversations about splitting” says Evans, “it was quite straggly. The three of us would get together and rehearse for a bit, not quite knowing what we’d do with any of it. It petered out. There was no conflict or anything like that.”

And so, at the end of 2002, Life Without Buildings split. “I was devastated” remembers Andy Miller, who had hoped to continue working with the band, “at the time it went over a lot of people from Glasgow’s heads.” There was a small news item in the NME, who were busy-chest beating about the New Rock Revolution, editor Conor McNicholas’ brainchild to rebrand a selection of garage punk retroists in the language of future shock. Perhaps Life Without Buildings’ could have fit with that moment, but they weren’t those type of people.

Time passed, and all of the band would take up jobs in the art world – Sue Tompkins going on to have a successful career as a visual/performance artist. Something, though, was happening to the music that they had left behind. “I’d travel, and I’d keep getting people asking, have you heard of this band Life Without Buildings?” says David Shrigley.

“I’m constantly meeting people who love that album” says Paul Thomson, who would put ‘New Town’ on Franz Ferdinand’s 2014 Late Night Tales compilation. When Pitchfork gave a glowing review to Live At The Annandale Hotel, the band became aware that the record had achieved cult status amongst US indie DJs, crate-diggers and bands.

“The people that liked us, in general, tended to be younger millennials” says Johnston, "often on the left, often queer or non-gender confirming, that really validated it for me. Not just people like us, but good people like us, and that’s probably all that you can hope for really.”

And then, something extraordinary really did happen. In December 2020, at the end of a difficult year, a fifteen second piece of music began circulating on social media platform TikTok. It was the intro to ‘The Leanover’. It had little to do with the band itself – TikTok hits are, for now anyway, tricky to engineer – but a snowball effect of young women (and it overwhelmingly is young women) seeing the video and forming their own video response.

At time of writing, the intro to ‘The Leanover’ has appeared in at least 100,000 videos, putting it alongside sea shanties and Boney M’s ‘Rasputin’ in having become TikTok famous. There’s the knock-on effect too – ‘The Leanover’, overlooked at the time, now has 5 million streams on Spotify. What art will the people making TikTok videos to ‘The Leanover’ go onto create?

“I never really thought about gender at all when I was actually in the band” says Tompkins, “but that’s what struck me immediately when I did look at TikTok, I think that’s what struck me immediately. Quite moving really.” The band that sidestepped briefly from art into music, memorialised by new technology in homemade video art from around the world.

Any Other City is reissued on vinyl by Rough Trade on April 23