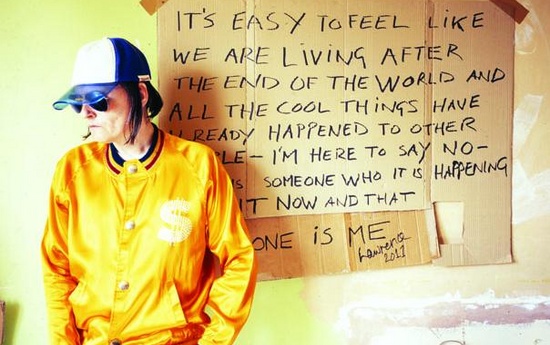

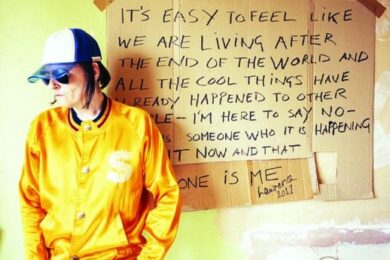

There are outsider musicians, and then there is Lawrence. He was the featherlight frontman of indiepop legends Felt, before he became the gaunt glam-rocker of Denim and Go-Kart Mozart. In the 80s, he used to peer out from the pages of the Melody Maker, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, like a softer-looking Pete Doherty. He now crosses the street in a baggy green sweatshirt that shrouds his worryingly skinny body, wearing a dirty baseball cap of which he owns several copies.

This cap played a big part in director Paul Kelly’s recent biopic about him, Lawrence Of Belgravia – the story of a musician who still believes he can be properly famous. The film also touched on Lawrence’s battles with drugs, bailiffs and mental illness, but there’s other shadowy things about Lawrence that have remained unexplored. Such as whether the rumours about his relationship with a Felt fan in the 80s are actually true – that fan being a Windsor girl called Sarah Cracknell who went on to sing in Saint Etienne. Then there’s the questionable nature of several lyrics on the recent Go-Kart Mozart album, On The Hot Dog Streets – an often brilliantly funny rollercoaster of glam-rock, pub-rock, DIY demos and disco – which sails close to the wind in terms of sexual and national politics. This is the Lawrence that is talked about far less: the darker character that lurks behind the lovable eccentric.

But Lawrence is engaging, entertaining company in the flesh. He’s personable, intelligent and daft as a brush. We buy teas from the cafe across from his council flat, and take them up in the lift. Lawrence HQ is a tiny pop nut’s dreamland of art books and old music magazines. On The Hot Dog Streets, in many ways, is an extension of this world – even its lavish liner notes are full of references that aim to expand our minds, as well as play with them. These include lists of fake band names that Lawrence would like us to use (Tincan Dropout, Spacebob, Benny Jag & The Birdcage Hypes), artists Lawrence played as he was making his album (Wiley, Irish punks Gout, "Sh Sh She Sheena Easton") and books he read, many of which do not respond to a Google search (although if you find TT Brassington’s Parading Without A Permit: Touetic Filthy In The Female Mind, or Beryl Ainge’s The Scum Rises On Holloway Road, let us know).

The liner notes also feature a Small Ad, which describes, Lawrence explains later, why he "wants to be alone". The person posting the ad is "moribund" and "misanthropic". Likes "solvent inhalation" and "total isolation". He seeks "a vigilante type into peeping" who is also into "extant solipsism". "For me," Lawrence adds, "it shows my fans that I’m never going to have anyone else. I’m still living like the libertine in the garret. I’m always there for them."

In Lawrence Of Belgravia, you said you always wanted to be famous. After glowing reviews of the film, and similar praise for On The Hot Dog Streets in the press, you’re probably the most famous you’ve ever been. So how does it feel?

Lawrence: Well, we were in The Times twice, which is kind of unheard of. I mean, I’ve been really fortunate with this record: yeah, I reckon this probably is the most famous I’ve been at one point in time. I mean, I’m still not [takes a breath] ‘Famous’. I still have to go to the supermarket. I still walk down the street. Those people in that café across the road don’t have a clue who I am. I’m still the guy that comes in for a cup of tea every day. So I don’t feel famous.

Do you read your reviews?

L: Gosh, yeah, of course!

And spend time picking them apart?

L: [shakes head] I never, ever pick them apart. I would never be angry about anything said about me that I didn’t agree with – never. Because that’s someone’s opinion and you can actually learn something as well. But for me, fortunately, in my whole career – well, it’s not really a career – the whole time I’ve been in music, I’ve hardly had a bad review, really. Usually people genuinely want to get me to the next stage… they want to help me get up the ladder.

How long have you been working on this record? I’ve read that some of the tracks are leftovers from your Denim days.

L: Well, it should be a triple album, really. But there’s a mini-album coming out in a few months’ time, called, you know what, I should get a piece of paper, because I usually write stuff down for people in interviews…[goes off, comes back with paper]… yeah, there’s a mini-album coming out and that’s called [writes this down] Mozart’s Mini-Mart. See, since the beginning of Go-Kart Mozart, in 1999, we’ve been recording stuff. And what I’ve done on this is put it all together with anything that was left over, anything that I’d started but I hadn’t finished. And that’s why there’s two songs that were Denim songs – ‘Lawrence Takes Over’ was ‘Denim Takes Over’, and everyone knows that, and there’s one called ‘The Sun’. I wanted to do a triple album of everything and then move on to something different… and then if next year or something, I just think, I want to do something different, I might just change totally. [shrugs] I don’t know really. It depends on how this sells. If this sells really well and everyone buys it, then I’ll carry it on. But if it just does what I normally do, then I think I’m going to put it to bed for a bit, let people catch up. That’s what happened with Felt, we knocked it on the head and no one was really interested. Then, many years later they were… I knew people would be interested in it in the future. But I want to move on, keep going forward and doing new stuff.

In terms of musical style, too?

L: Yeah! Something completely different, completely different! But what I’ll do is promote Mozart to the end, that’s what I’m trying to say. And we’ll do live starting next year, and then we’ll do festivals, hopefully or definitely. And then the whole thing will be a long campaign.

Is it fair to say that Go-Kart Mozart is the band of yours that you’ve cared about the most?

L: No, no – this is the band that I sort of threw together because I couldn’t do anything grand anymore. I’d kind of put so much of myself into Felt and Denim that I literally couldn’t do another group of that scale again. With Felt, if you look through back issues of the music papers in the 80s, we were in the independent chart every week, constantly playing gigs, whenever they were offered. Denim was even harder than Felt, because even though I was on a major label [Denim were on EMI in the mid-1990s] and there was a lot of money involved, let’s say it was equally as difficult to get recognition. So after I was dropped, after the single was melted down [Denim’s 1997 single, ‘Summer Smash’, was cancelled after the death of Princess Diana in Paris], I thought, OK. I couldn’t stop, I couldn’t retire, I had to do something really simple, really thrown together, ad hoc. So I thought: I’m going to approach music like you would a b-side. And that was the idea – we’re the very first b-side band. So you kind of have a more light-hearted approach to everything.

I’ve heard you weren’t happy with the Go-Kart Mozart album before this [2005’s Tearing Up The Charts].

L: Well, it was meant to be a book with a CD, like a Beano annual or something, you know that kind of paper? It was meant to be that, and on the back it would have a sleeve for the CD. One minute… [goes to shelves, pulls out groaning scrapbook of reviews, photographs of bands and models and chart rundowns] This was the book, but they wouldn’t print it for me. It was all like collages basically, collages and charts, mad things like that. [sighs] I do want to print it one day. And that was why I was really upset when that record came out. And it wasn’t even out on vinyl!

But this time your album is on vinyl…

L: Of course! You know, a CD in a plastic jewel case is such a rip-off. I’m glad CDs are dead now, because I’ve never taken to CDs, I’ve never collected them, even when they first came out, I was against them. Even for Record Store Day this year, we did a single , and had to do a CD, but even the CD is a square! [leans in] CDs are rectangles, you see, and that’s why I hate them, because I hate rectangles.

And your CD single was made of cardboard, so no plastic jewel case…

L: That’s exactly what I mean! No plastic, it’s all cardboard. So I’m really happy, because if you do have to buy the CD, it’s actually a replica of the album. And it’s a square! [shakes head] I’ve gone right off the point, haven’t I.

How do you survive financially?

L: Well, you don’t. You don’t have any money…[speaks at length, off the record] I’m in a terrible situation really, whereby I think I’ve got something to offer, because obviously I’ve still got an ego, but I think I’m offering something which is much better than so many other people that are making a fortune off music. I think, why should I give it up? Why should I give up the thing that I love, the only thing that I’m good at, when all these other people are getting deals and making enough money to live just through one advert? It’s not that I’m at all bitter about anyone else making money, I’m really not, honestly. I think good luck to everyone! But if I give up now, I might never get a chance to be a professional musician. I know some people change when they get older. You’ll see it when your friends get older – I’ve seen my friends who are in bands, who happen to have a kid, and that’s it. Because suddenly they’ve got this other life to provide for, they have to get a job…they do it for a while, but you can see it fading away. They know it’s all over.

Have you ever wanted those things in your life – a wife, a family?

L: Oh god, never! I mean, the last girlfriend I had walked out on me in about 2000, and I haven’t had a girlfriend since. Whenever I’ve had a girlfriend, they see my music and my group and my career – not career, what I do – as like another girl, like a threat, and we’re constantly arguing about this other person, which is my music world. Although I know some people are lucky. [suddenly gets excitable] I was watching that brilliant Bowie documentary the other night, did you see it? There’s a brilliant bit where his wife, Angie, walks in, and it’s a beautiful relationship and she’s really sweet. And she doesn’t want to get in his way, he’s having his makeup done, and she just comes in to say, "I’m here", and she doesn’t hang around the dressing room. That’s really nice. That’d be nice.

That didn’t last though, did it?

L: I know, but at this point in their relationship it’s working really well. But I don’t know a relationship in the music business that’s survived. I don’t know any. So when my last girlfriend walked out on me, I thought, I’m never going to have a girlfriend again. For me, it’s all or nothing. It’s like I can’t get a job, because it will impede on the band; I can’t get a girlfriend because it’ll impede on the band. For me, what I do is all-encompassing. I haven’t seen that, and I don’t see that in anyone else.

In the last year, you’ve been much more visible in other ways too – I found a YouTube clip of you interviewing the LA band, Girls, which was a surprise!

L: [grits teeth] I did that for a magazine called Magic. There’s always a back story, and that’s not the sort of thing I would do, but Magic were really prominent in helping me survive in a way; not helping me survive, but in France they promoted me, even when nothing was happening, and they still write about me. So they said, can you do us a favour, we’ve got this band, Girls, and they really like you, do you mind doing it for our online thing? So I did it as a favour for them.

Did you enjoy it?

L: No, not really. I’m a musician and a writer. I don’t want to be an interviewer. I don’t want to be a DJ either. I mean, I did a one-off radio show for 6 Music, and quite a few, well two or three, people have come up to me and said, ‘Oh, you should do a radio show.’ But I don’t want to veer off, because that would mean I’m that personality treadmill. I don’t want to be on that. I’m Lou Reed, I want to be Lou Reed! I’m Lou Reed, I’m Bob Dylan, I’m in that bag.

You were on The One Show last year too, on a segment about banned records introduced by Gyles Brandreth. How come?

L: Honestly, that’s not the kind of thing I want to be on either. But they asked me to be on it, and Paul [Kelly]… well, me and Paul agreed it would be amazing if we got Gyles Brandreth on our film. That was the only reason I did it! But because they wanted to film it in this café with people talking and everything, we couldn’t film it properly, and Paul’s film was all corrupted…[sighs] so I took a massive risk, risking my credibility to go on the One Show.

I think people really liked it.

L: You know what, they promised us two and a quarter minutes, and then when we were on it was like five seconds! I’m a bit – no – I’m still really pissed off about that.

Would you like to be on TV music shows these days?

L: Yeah, a music show, but I don’t want to be on Celebrity Juice, or be one of them people on Never Mind The Buzzcocks. I hate that Never Mind The Buzzcocks. That is like the nadir of pop celebrity, that is, oh my God. Seeing pop stars make fools of themselves [shudders]. My whole thing is you can’t touch me, you can’t get near me, you can’t just phone me up, you can’t see me online, you can’t talk to me. There’s a lot of mystery. There’s a lot of rumours about what I’ve done, what I haven’t done, I haven’t said yes, I haven’t said no, I don’t admit to anything. And that’s the way I want it. That’s the way I want my pop stars to be.

Have you always wanted to be like that?

L: Yeah! Even when was a teenager, I’d be, ‘We’re going to do a band and get out of this place.’ I’d look at some of my friends, and think, how come I’m the only one that wants to be in a band? The funny thing is, now everybody wants to be in a band. When you see home shows, there’s always a guitar on the wall, and practically everybody wants to go on a talent show of some kind… but now it’s actually happened, it’s horrible.

Why horrible?

L: They want to be famous for nothing. There was a time when you had to be famous for doing something. If you’ve got nothing to say, don’t say it. There’s nothing worse than people clogging up the airwaves. [smiles] We used to say in the 80s, all these bands are clogging up the airwaves, and none of us can get on there. And then in the ’90s we all got on there!

How do you remember that period?

L: You mean when indie took over the mainstream? It was great, because it was like vindication. When we first started, bands like us, we thought this stuff should be on mainstream radio. This stuff could easily be on the telly, we could easily be on The Old Grey Whistle Test. Even The Smiths couldn’t get Radio One airplay. Orange Juice had only one hit!

And then in the early 90s, Denim were on Later with Jools…

Yeah, what we’d all worked so hard for, it had become this thing called Indie, and it became a brand. Really, what we’d all worked for, all of the early Creation bands too, we’d fought them wars, you know, for the Oasis generation.

Do you think that was a good thing?

L: I thought it was great. We should have been mainstream before that anyway, that kind of music. I remember the turning point – someone saying one night, come and see Pulp. And me going, oh Pulp, they’ve been about for years… and it was phenomenal, like, oh my God, you could just tell it was going to be so massive. It was the night when I just thought, we can all make it now, all of us can do it, and it was only because of short-sighted A&R staff that we didn’t all make it, because Denim definitely should have been up there with all those people. I mean, the idea that I had for a group called Denim was practically Britpop By Numbers. I wanted to have a really English group that was all about England, and people from the provinces singing in Cockney accents. That was my idea!

But you didn’t play live early on, did you?

L: I didn’t want to, because I thought that live music was finished because of the DJ culture that had happened since 1989. And our A&R actually agreed with me – you know, there’s no point schlepping up and down the M1 anymore: those days are gone. But I was very wrong, really wrong. We did a few tours later, an arena one with Pulp, but it was too late really. The stage was always there for us and we just didn’t get on it. Ha! [grabs earlier sheet of paper] Let me just write that down. [scribbles] That’s brilliant! "The stage was always there for us and we just didn’t get on it." [leans in] See, I see my interviews just like an album of singles. Together they’re all the same. I want this to be as brilliant as a record!

OK, answer something I’ve wanted to know for ages. Did you go out with Sarah Cracknell for a while in the 1980s – around 86, 87?

L: Yeah, yeah I did.

Aha!

L: How did you hear that then? That rumour?

I’d read a rumour about it on the internet. And I know Sarah used to follow Felt around in the ’80s with her friends – she mentioned it when I interviewed Saint Etienne earlier this year. And the Felt song ‘She Lives By The Castle’… well, Sarah’s from Windsor, so I assumed it was about her.

L: Ah, but that song’s not about her. When I was going out with her, right, I made that title up because I was hanging around Windsor. The title came into my head, but the song’s not about her at all. But people did inspire me for titles. Like [Felt’s] ‘Get Out Of My Mirror’ – that was me getting ready to go out one morning with an old girlfriend, and I just said, get out of my mirror, and thought, ‘Ooh that’s a good title.’ Things like that come about when you’re going out with people… and me and Sarah were driving past the castle one day, Windsor Castle, and it just came into my head. But the actual song isn’t about me and Sarah, because we had a really great relationship and we never fell out. And you know, it’s nothing like the song. And we’re still friends now. Mmm.

Did you know she made music?

L: I mean, for the first four or five months, she didn’t even tell me she was a singer. She wasn’t trying to push her music career or anything. I was really shocked. She’s very humble with it, Sarah, very very humble.

And you say you’re still good friends?

L: Absolutely. We’ve never fallen out. I think because I lived in Birmingham and she lived in Windsor that was the problem, really.

Did she introduce you to any music?

L: Yeah, she did. Her and her friends used to all hang out together in a group and play music I would never listen to. Like Prefab Sprout and, gosh, groups I used to be very snobby about, groups of that ilk. Yeah, she got me into a lot of 80s pop stuff that I wouldn’t have listened to. I think Sarah taught me a lot there.

How long were you together?

L: We hung around together a couple of years, but we only went out for about six to eight months, really.

And the break-up…

L: We were living far apart, and she came down once to see me and said, ‘I’ve met a guy I really like, and think it’s going to be long-term.’ And that was it, and I was fine. Because we knew because of the distance it couldn’t really last.

So she didn’t break your heart?

L: Oh honestly, it wasn’t liked that at all! She just warned me, I’ve met this guy, I think I’m going to go out with him. And it was fine, it was really amicable. And that was a guy she went out with for years and years and years. Not the one she married, the one before that. I’ve never… this is the first time I’ve spoken about it really. [shakes head] They were a good bunch, that lot, that started out following Felt around, driving around the country, and a lot of those people went on be in bands and have hit records and be DJs and things. There was another character who ended up in Soul Family Sensation, Johnny Male, and he ended up in Republica. And Andy Weatherall before he did Boys Own, he came to lots of our gigs, as well as Primal Scream in the early days, and we know what happened with them. And there was a guy in Flowered Up – all of them were Sarah’s friends. And because Windsor was a small town, all the musicians hung out together. There was a closeness between us all, which was really lovely.

Talking of music… On The Hot Dog Streets is very much in the same style as previous Go-Kart Mozart records, but there’s even more synthesisers this time…it’s a bit full-on perv-disco, isn’t it?

L: Yeah! I mean, for me with music, you have to have a foot in the past and a foot in the present, and then you end up in the future. So, as well as it sounding very 70s-influenced, I think it sounds very modern day as well. If you read the list on the album, there’s lots of modern records like ours. Like Wiley, there was a brilliant single by him last year, Numbers In Action – for me that sits very nicely with the 70s synth as well, because the sound of the 70s was so futuristic, it was never superseded. There’s a few other modern ones like that, which I like…what’s her name, that mad girl with green hair? Nicki Minja?

Nicki Minaj.

L: Nicki Minaj! ‘Beez In The Trap’! And gosh, I think it really sounds like us too. Honestly, when I hear a record like that, it makes it all worthwhile for me. I really dislike people of my age who go, there’s nothing good any more, it’s nothing like the old days. It annoys me so much. What I say to them is, look, all you’re saying is you’ve stopped listening to new music now and you’re sticking with what you grew up with. And that’s fair enough, but don’t criticise what’s going on now because if you went digging around you would find stuff. That Nicky Minja record is as good as any record in the 70s!

You sound like a campaigner!

L: I am! Gosh, I feel like I’m on the frontline in a war sometimes. I’m trying to break through that frontline to get to the other side. To victory! I think when you’ve had so many knockbacks and you’ve been kicked down, you can go either of two ways. You can go really bitter, and get really caught up in blaming everybody else for your failure, or you see the humour in it. You can see the absurdity of trying to do what you’re trying to do. So I tend to just sort of laugh at things instead of getting angry and bitter… but in the next batch of songs I’ve got, it’s a bit darker. It’s a lot darker.

Darker stuff in what sort of style?

L: You know, I’m a songwriter, it’s not all one style.

What are the songs about?

L: Yeah, but I mean… [shakes head, holds out hand] I’m going to hold that back for now.

In Lawrence Of Belgravia, your difficult times are referred to, but only in passing – your depression, your Class A drug problems in the past…

L: [sits up, shakes head] I don’t want to talk about that. I want to just brush over that. Is that OK?

But you didn’t mind these things being mentioned in the film in passing?

L: I think the best thing to do is to let people see stuff, but never talk about it. I hope that’s OK.

More mystery!

L: Of course!

You’re famously not a fan of the internet too. In the current album liner notes, you knock the downloading of music as "pure bad manners/sheer affrontary" to your craft. Have you ever wanted a computer?

L: Computers? No! Pop stars with computers… What I don’t like is a pop star doing like a diary thing for their fans on the internet. The worst one for me – I cut it out of this magazine, it was amazing – was a tweet by Lily Allen, and it said: "Just had a lovely iced bun and a cup of tea". That sums it all up for me. Who gives a fuck? Why would you put that on a thing? Who cares? There’s so many things going on about that one line, to me it’s like everything that’s wrong.

Wouldn’t you like to know about Lou Reed’s iced bun?

L: No! I want Lou Reed to push me down the stairs or tell me to fuck off. I would never go up to Lou Reed anyway and go, "Hey, I love your songs", I just wouldn’t. I mean, if I was in a room and he was there, I wouldn’t say anything.

You must have had met a few people you loved over the years.

L: [shudders] I’ve met Tom Verlaine. In Felt, we were playing at the Boston Arms in North London, and there was a German girl who was mad on us, who worked for a magazine called Spex [writes on paper] s-p-e-x, right. And she was going out with Tom Verlaine, just by the by and she brought him backstage. And he was embarrassed, I was embarrassed, and it just shouldn’t have happened, you know? I just shook his hand and we just stood there, and we didn’t say anything. [sighs] But still, Marquee Moon is still my favourite album, ever. I only play it on a sort of hot spring day, because that’s when I bought it. And when that time comes around, I put it on and it takes me back to 1977, to May and June 1977 specifically, when I bought the album. I still remember that beautiful hot day, and I went to town on the bus to get it.

How old were you?

L: I was 16. And I came back and put it on, it was, oh God, this is it! I knew it was the greatest record I’d ever heard. It still is.

Looking at On The Hot Dog Streets as well as the lists of books you’ve read, and music you’ve listened to on the liner notes, I get the sense you’re trying to say a bit more about the world, too.

L: I am, yeah.

‘Come On You Lot’ talks about how our "country’s lost its spine /All we do is moan and whine", and dismisses girls who want "silicone tits". But there’s a few lyrics which also made me uncomfortable. In ‘Mickie Made The Most’, there’s the lyric: "The little girls shine, they’re looking so pretty / when we lift their tiny skirts, oh, they blush a pure red." Do you worry about how a line like that might sound?

L: No. What did you think of that line?

I thought that it was a bit Gary Glitter, because you said "little girls".

L: Is it suggestive?

Yes, it is suggestive. Do you worry about doing things like that? Or do you just put things like that in to wind people up?

L: Yeah. Not to wind them up, but I just like to test people’s boundaries, because I don’t have any.

It did make me feel uncomfortable, though.

L: Really? I don’t specify the age [of the girls], though.

You do…

L: That’s in your mind.

You say tiny. Lift their "tiny skirts".

L: But that could mean the length. It’s in your mind. No, it’s funny that you say that. The only time I thought of that was when the guy doing the backing vocal, I thought, he’s got a kid. And when he came in to sing it, I thought, he’s uncomfortable singing that. I noticed it, and I thought, wow, I think he’s a bit uncomfortable. And I thought, that’s weird. But I didn’t say anything, I just thought, that’s in people’s minds. You know, you can take things how you want.

Did you feel bad that you might have made him feel uncomfortable?

L: No, I just thought, wow, I can see he feels funny singing that line. It just struck me for a minute. But then we carried on, he did it anyway, he didn’t say anything.

Would it upset you if other – say, female – friends felt uncomfortable with it?

L: No, because for me I like young girls. I’m not talking about… if I talk about it, I justify it. I like teenage girls, you know. If somebody thinks I’m talking about something, not teenage girls, you know, like…

Kids. Like kids that are underage.

L: If you think I’m talking about kids, then that’s in your mind, it’s really in your mind. Because if you read all my other lyrics, you know, I’m not that kind of person. I’m a real moral sort of person, really, if you knew me and you knew about me. And it is, like you say, a bit of a tease. Like that song, ‘A Song for Europe’, on the Denim album, and it sort of says, "little girls everywhere". And that was the first time I think I’d done a line like that, and I remember doing that and thinking, ‘Oh! People are going to misinterpret that.’ Good. I’m glad about that. I think you test people’s boundaries.

But surely people might think less of you because of that line?

L: I don’t know how you could, because I haven’t said anything bad. If you think it’s something bad, then that’s in your mind. Don’t you think? That’s a writer’s job: to put a mirror up in front of you, right in front of your face. And sometimes you might go, ‘Wow, I’m uncomfortable with that.’ Also you could learn from it or you could test your own boundaries.

I’m sure the lyric about the allure of vaginas on ‘I Talk With Robot Voice’ will test a few other people too, although I admit that I found that pretty funny.

L: I know. If you look at it, if you reason it properly, it’s like, gosh, there’s actually nothing really wrong with it, but yeah, it’s my job to make people think, I think. Because for me, Bob Dylan or someone, he’s made me think. I mean, look at Lou Reed and ‘Heroin’. When he wrote that song: wow, what a thing to put out there. Or ‘Venus In Furs’, about sadomasochism. And it’s a writer’s job, in the same way that it’s an artist’s job to paint what’s in his head. There were people like Aubrey Beardsley where a lot of people could be so embarrassed or upset by what he drew, and then other people say they’re the greatest Victorian drawings ever done. It’s in the eye of the beholder, it’s in the mind of the beholder, it’s an artist’s job to put that mirror up in front of its public and to reflect it back at them. And that’s what my job is.

And then we have ‘Blowing In A Secular Breeze’, which is very gung-ho looking at Britain’s glorious past.

L: Well, what I wanted to do write a song answer to ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’. A modern update! I thought of the title first, and that it could be a theme for another generation. People could sing it all together, but didn’t quite turn out that way. It’s got life of its own now. I guess it’s not for me to say whether it’s an anthem or not.

There are lines about Europe that suggest you’re not particularly keen on people coming into the country. Would that be fair to say?

L: Well, I’m like… I’m in that Ray Davies camp. You know, I love the England of, what’s it called, The Village Green Preservation Society. I’m that kind of songwriter. I long for that kind of past, that time when you were a child. And you cling onto that really, but you try to live in a modern world as well. And you try and find a space where you can exist between the past and the future and when you try and find that place, you can’t help criticise things, because you see things that are wrong.

But the line "it seems we left the back door open far too wide" – is that about immigration?

L: That was [about] the Common Market. It could refer to the initial welding together with the Common Market, when we first joined, and also, obviously, it could relate to today as well. But it’s not about what you were thinking it’s about – immigration. Is that what you thought?

That line is dangerously vague.

L: Yeah, but I was referring to Europe in the 70s, when we entered Europe in earnest, and it just seemed like we left it open too long without keeping a check on things.

Keeping a check on what?

L: Some people want Europe to be a superstate. But me, my generation, we just want to be little old England with our own currency and village greens. That’s what I meant. The other thing is in your mind.

You’re making a political point, then?

L: I am, but I like to put it in a song and try not to explain it, because you get in a right mess trying to explain it. Like now! It’s really difficult, and you don’t want to express the wrong point. I just like to put it in a song.

So, do you vote?

L: Nah. No, never.

Never?

L: Never have.

Because there’s no one want to vote for?

L: I just don’t vote, no. I don’t really feel happy talking about politics. I hope that’s OK.

Well… I guess the best way to wrap things up is to go from the sublime to the ridiculous. On The Hot Dog Streets also features a song about a market trader and cauliflowers called ‘Ollie Get Your Collie’…

L: Yeah. I used to work on a market and there was this little kid who used to stand there all day, he’d got this gravelly voice, going, "Ollie, ollie, ollie, get your collie." It just must have stuck with me all my life. This funny little kid. And it’s just about being on that market stall.

And I do like the line in ‘White Stilettos In The Sand’ about boorish men trying to get off with women… you call them "gorillas in your midst", with a good stress on the "d".

L: Hooray! Good, I’m glad you liked that. Because sometimes you write this stuff and you just think ‘Does anyone even get it, does anyone even understand what’s going on?’ I tried to pronounce it properly so that they’d get it.

But what I really want to know, of course – going back to those liner notes – is whether anyone’s responded to your final request in them. ‘Thinking Of Buying A Gift For Lawrence? Book Tokens – Record Tokens – Ta Very Much.’

L: You know what, I had a call from Cherry Red the other day saying I had some post. So I hope there’s some there. [smiles] You never know! A book token so I can have a good Christmas! Nothing wrong with a few gifts for my efforts.

On The Hot Dog Streets is out now on Cherry Red. Mozart’s Mini-Mart is not yet scheduled for release. Lawrence of Belgravia is out on DVD later this year