"I think that scientists have the same problems that artists do," Laurie Anderson says down the phone line. "They have a lot more in common with artists than you’d think, because they don’t know what they’re looking for either. And they do things in a similar way to artists. They get a kind of idea, just a hunch, and then make stuff." She should know, as the first and last artist-in-residence at NASA – a post she accepted because she, "Loved it that they had no idea what it was, so I just made it up" – she spent a lot of time with scientists. Just being a "fly on the wall," as she says, for two years, meeting people and talking to people ("really fantastic conversations") she would never normally have met in the art world. But she insists, "Like artists, they have to answer the same question: How do you know when it’s done?"

In The End of the Moon, a long poem that became a musical performance, a kind of ‘report’ and summation of her time at NASA, she says, "The thing I hadn’t realised is that stars aren’t there in a random way." The words delivered in her trademark halting, quizzical tones, electronics gurgling and arpeggiating underneath, "There’s a secret order in the sky. And the colours of the stars tell you their age. Their origin. How they began. And I’d never realised this before. I had never realised that I was living in an enormous clock." So two years of stargazing becomes a meditation on time, ageing and finitude. A line of flight away from the earth at a time when it had become, for Anderson, enormously problematic to think of herself on Earth – or rather, in that particular part of the Earth she inhabited and had grown up in. That is, an America that was everyday revealing its complicity in brutality and imperialism.

"I was very angry at what was going on," she says of the Iraq war, the seemingly endless revelations about state complicity in torture. "And also you know how, to some extent, your self-image does have something to do with your opinion about where you live. That’s what was really on my mind when I statred working on this record." The Homeland album was developed over several years on the road, playing live, often improvising, with any number of different musicians, "Mongolian players, jazz guys, pop players," until finally she found herself with "100,000 sound files." An early attempt to recreate the songs she’d written while travelling in the studio had just sounded "leaden" and the record label’s budget for studio recording had soon run out, so she had set to work on the slow painstaking process of piecing together this enormous puzzle, "Random lines from here and there: A viola line from Sweden a year ago; a guitar line from Mexico City last year." This nightmarish picture of teeming complexity – no two parts recorded in the same room, the same time, the same tempo – was soon driving her, she says, "crazy … And I would literally still be working on it this evening" if her husband, Lou Reed, had not stepped in.

Anderson and Reed married in April, 2008, and they’ve collaborated musically numerous times both before and since. Recently they were booed and jeered at the Montreal Jazz Festival by an audience evidently expecting a few hits who were greeted instead with an intense free improvised work out with John Zorn (the performance was very well received by critics). Recently, the couple raised eyebrows with high-frequency concert for dogs in Sydney. On Homeland, Reed’s role seems to have been largely in the realm of checks and balances. "That’s done let’s move on. And I was like, man that’s not done. I’ve gotta put other… That’s done. Let’s move on. Leave those blue notes in. Leave a little air in there. He’s a great producer."

Despite the album’s opening salvo of, "It’s a good time for bankers," Anderson insists that over the course of the Homeland‘s seeming eternity in production, the situation felt like it had changed and most of the political material ended up on the cutting room floor (as did those Mongolian musicians). "Basically, when the Right is in I write about politics, and when the Left is in, it’s more poetry." But in spite of the shift in gear, the record still has its teeth. For Laurie Anderson, ‘the personal’ never means any straightforward maudlin lullabies. Love may be sweet, but it is messy, contradictory, even dialectical. Second track, ‘My Right Eye’ centre around an image of two eyes shedding tears, "They fall from my right eye because I love you / And they fall from my left eye because I cannot bear you." This kind of paradoxical situation is typical of the mood of a record that doesn’t offer "neat answers. We’re asked to summarize things so often, to resolve things that are kind of unresolvable, and it just doesn’t work like that."

This sense of being oppressed by the demand for certainties is enunciated most explicitly on the single, ‘Only An Expert’, a track about a technoculture of fake scientism, a politics disguised as post-political administration and swallowed by the language of managerialism. "Only an expert can deal with the problem. And just because you lost your job, and your house and all your savings, doesn’t mean you don’t have to pay for the bail-outs for the traders, and the bankers, and the speculators. Because only an expert can design a bail-out. And only an expert can expect a bail-out." Through buzzing guitars and pulsing house beats, the song describes a situation where, "You have so many people trying to convince you that, oh, I’m sorry, but the economic situation is so complicated. You wouldn’t really understand it. It’s so intricate and let me just rob you blind while I try to baffle you with statistics about how complicated banking is, y’know?" But lest we think bankers are the sole target for Anderson’s ire (deserve it though they may), she is just as furious with certain, "Other experts, starting with Oprah Winfrey. This is a show that basically starts from the assumption that there’s something wrong with you."

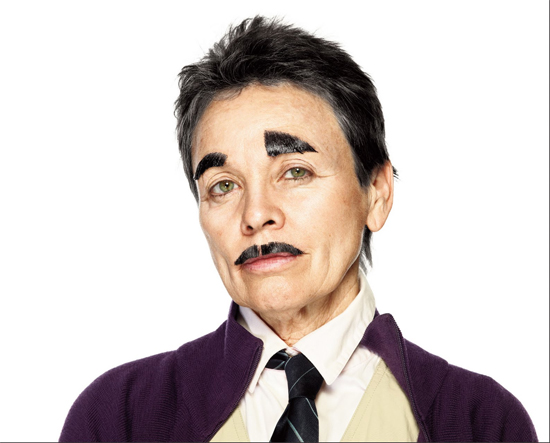

Talking to Laurie Anderson on the phone can sometimes be a little like having a whole crowd down the line. She has a tendency to illustrate her comments and stories with a gallery of different voices and personas, mimicking TV ads, friend and family members, singing and humming to me down the phone lines. It’s a little like being at one of her shows. Onstage, the most longstanding of these alteregos even has a name, Fenway Bergamot. First introduced at the Nova Convention, an event organised by Semiotext(e)’s Sylvere Lotringer by way of homage to William S. Burroughs, enshrining him as some sort of countercultural saint. Anderson performed along with Frank Zappa, Philip Glass, Patti Smith, John Cage and even Burroughs himself. Under Burroughs’ influence, Anderson’s ‘voice-drag’ alterego, created through live pitch shifting of her own voice down an octave or two, became the voice of authority, "A blowhard who is always following the rules – completely ridiculous rules."

With time, Bergamot has mellowed, and Anderson’s relationship to her creation has mellowed too. Nowadays, she tells me, he’s "Much more odd and eccentric and… tender. It’s almost like knowing another person." I can’t help but ask if there’s any of Lou starting to creep into the character, but she insists not. "I would say it reminds me more of my brothers and my father and my uncles, who have that timbre in their voice. In fact I just did a show in San Francisco, and my brother was in the audience and it was so weird to talk to him afterwards because he was like, that was like hearing my own voice." More than anyone, the character reminds Anderson of her own grandfather a "somewhat dark and pessimistic Swedish sort of someone… a fabricator." She describes him, "This guy who came from Sweden, according to him when he was eight. And then he got married when he was nine… I mean who knows where he was from even? So, it’s this sort of character who’s kind of lost, and I can really relate to that, because I often feel kind of lost."

"And you know the reason I really love the stars?" Asks Fenway Bergamot, on ‘Another Day in America’. "It’s because we cannot hurt them. But we are reaching for them." Perhaps the ultimate sign of a less "brittle" turn in the relationship between Laurie Anderson and her deep-voiced twin is that now he seems to be enunciating something of her own philosophy, a kind of pacifist striving for utopia. Both eyes wide open and sharp with critique at the same time. A contradiction that could almost be one of her own lyrics.