Many peoples’ introduction to Calum MacRae, otherwise known as Lanark Artefax, may have come last year in the form of the Glasz EP, the fourth release from Lee Gamble’s burgeoning UIQ label. A five-track record loaded with scattershot, splintered electronics that at times recalled the more experimental reaches of Autechre and at others the digitally rendered sheen of Holly Herndon, it came about fittingly after MacRae saw Gamble DJ to a small but up-for-it crowd at the return of the Bloc weekender in March 2015.

Finding inspiration in the new companions he made that weekend in the form of the collective behind Manchester label Cong Burn Waves as well as that set by Gamble – “It’s the only time I’ve seen a DJ and stood in awe unable to understand what I was listening to,” he tells me – MacRae returned to his Glasgow base refreshed with a new impetus which saw his work rate steadily increase, and his debut release come soon after. Arriving via the aforementioned Cong Burn Waves label during what he describes as a transitional period for his sound, MacRae set out pulling from a selection of samples that he had recorded himself for the tracks, some of which he continues to use now.

“I generally work from the same bank of sounds and I have these digital instruments that work organically so as to do very different things each time I use them,” he says, adding that working in such a way allows him to step into a self-created world and mould a sound within very specific parameters. Despite carrying various manipulated samples over through his work, the difference in the two years that have followed MacRae’s debut release and his latest offering for NTS DJ and former Young Turks affiliate Nic Tasker’s Whities label is immediate however, opting now to pare back the elements that make up his work resulting in something more refined.

MacRae has been developing his sound for years though, having begun experimenting with production software from the age of 15. Finding himself amongst a friendship group of music lovers before he was legally able to go to clubs, he would sneak into some of Glasgow’s best nights and clubs thanks to handy connections, soaking up the music of local labels such as Numbers and LuckyMe who were enjoying particular acclaim at the time. MacRae laughs his productions at that time off as “Hudson Mohawke rip-offs,” having then been a big fan of the Glasgow-born producer, but also recalls a distinct influence seeping into his work from the music of Warp Records staples such as Aphex Twin and Autechre who had been introduced to him by friends.

With an excellent new four-track record just out on Whities, we spoke to MacRae about IDM as a genre descriptor, connecting with UIQ and Whities and why he doesn’t enjoy making traditionally structured music.

Could you tell me about your first experimentations with production and particularly about getting involved with the Cong Burn guys leading to your debut release in 2015?

Calum MacRae: I’ve been making music for a while, since I was maybe 15 or 16, and that was just by myself. I actually got together with some friends from school and some friends of friends who started a radio show at that time in Glasgow on Subcity Radio called All Caps. At the time, it was me and a friend from school, Matt, and those guys were starting the radio show, so I just tried to muscle my way in. At the time, I wasn’t really DJing so I thought I’d try my hand at producing stuff. I just started making music with some early plans to put it out with those guys and I was still at school at that time and thinking about university, so nothing really came of that eventually.

I met the Cong Burn guys at Bloc in 2015. I have a friend who studied in Manchester and he was friends of those guys so he put us in touch at the festival, because he told me that they were thinking of setting up a label to put out weirder electronic stuff. At the time, I think John Howes [who runs Cong Burn Waves] had started putting together tracks for the first release that they put out which was the Haddon record, so we met at Bloc and I spent the weekend with them. It was great to sit in the chalets every night and just listen to and talk about music. At that point, they hadn’t heard anything of mine and I don’t think I’d figured out a sound for myself at that point, but they seemed like a great group of people to get involved with because we all seemed to be on the same wavelength of making music but not yet being at the point of releasing it. I got tons of inspiration from that weekend and I then went home and started making the tracks that ended up on that first EP that I did with Cong Burn over the course of three days because of this rush of energy from Bloc.

What were you listening to and producing around the time of the Subcity days?

CM: Glasgow had a thriving scene at that time because it was the point at which LuckyMe and Numbers were really breaking out. That was a really big thing for me because our group had connections with some of the promoters so we would be sneaked in to some of those nights. Between the age of 14 and 17, I was sneaking into these nights at a bunch of places around Glasgow hosted by some of my heroes at the time like LuckyMe and Numbers, seeing people like Rustie, Hudson Mohawke, Dominic Flanagan from LuckyMe and the Rubadub guys. The music I was making at that time could probably be described as Hudson Mohawke rip-offs. I always loved ‘90s IDM too though so I was making a lot of stuff that was really Aphex Twin-influenced as well. Around that time though, that whole scene which I think people were referring to as ‘wonky’ with stuff like Hudson Mohawke and Rustie was what I was really into.

How did you get in touch with Lee Gamble and get involved with UIQ after your debut release?

CM: It was almost a cosmic series of events. At Bloc where I met the Cong Burn guys, Lee played a stage at around 4pm and there wasn’t many people there. I think there were around 20-30 people in the crowd and everyone was just swaying to this amazing music he was playing. He was playing music that I felt I’d never heard anything like before. It’s the only time I’ve seen a DJ and stood in awe unable to understand what I was listening to. At that point, the first N1L release on UIQ had been released I think, and he was probably playing some other works in progress from other UIQ producers. He was doing all sorts of mad stuff with the mixer and it felt like some kind of spiritual spectacle. From that point, I had all these ideas over the weekend of what I was going to do after the festival.

Even at that point, I wasn’t that familiar with UIQ, but I went home after Bloc and made some more tunes that felt quite transitional. After that, I was working on a lot more and the music that ended up on the UIQ record came out of that period. I got in touch with Lee over email after looking into UIQ more because I felt that it was the perfect fit for my vision at that point. I hadn’t specifically made music to be released by that label, but I just felt that we were operating within the same sphere at the time. He got back to me quite quickly and we fleshed out the initial ideas together over the few months after that.

I feel like some people might be tempted to describe aspects of your sound as ‘IDM’ and I’ve indeed seen that term used in places. How do you feel about that tag?

CM: I’m not snobby about it. I know that some people don’t like it and famously a lot of the figureheads of that genre, or what people perceive as that genre, like Aphex Twin, Autechre and whatnot, they hate it. It’s come to represent, to me, a specific era and sound from the early-to-late 1990s. It was very much established as IDM when I discovered this music so I didn’t necessarily have a problem with that term. Certainly, I think that trying too hard to pin sounds and genres down is unhelpful, but of the many labels that might get thrown about, IDM is probably one of the least offensive. Also, it made sense in the beginning to use that term to refer to certain early Warp releases like the Artificial Intelligence records because they were moving away from the dancefloor and gesturing towards the idea that electronic music can be different from dance music. Maybe as a catch-all term for music that doesn’t comfortably sit within the dancefloor and is a bit more experimental, it’s quite silly, but I don’t specifically mind it.

Tracing back to you talking about being into Aphex Twin when you were first messing around with production at the age of around 15, how did you discover music like that?

CM: The first proper electronic music I probably heard was [Aphex Twin album] Drukqs which is great. I’m so pleased it was that record that I came to first because I went from listening to indie music that a lot of people at that age are into to being thrown in at the deep end with music like that from Aphex Twin. I also remember hearing Flying Lotus at around that time and that was also thanks to a lot of the people that I was hanging out with in Glasgow at the time. I think my friend Matthew introduced me to both Aphex and Flying Lotus, and that point coincided with Flying Lotus getting quite big and then labels like LuckyMe that I then got into also getting big.

One of the key elements I pick up in your work is the use of space and silence between everything else, so have you always been drawn to using that kind of dynamic in producing music?

CM: I think that goes back to the idea of carving out a space for yourself and finding your own sound palette. If you can inoculate yourself against people copying you because your sound is distinct enough that you can hear other people’s influences while also being original enough to avoid people brazenly ripping it off, that’s where you start to build a world for yourself as a producer. I try to step into that world as much as possible and imagine that I am scoring some kind of space, but not in an overtly conceptual way. A lot of producers that I’ve found influential also do that, most obviously people like Autechre and Aphex Twin. With electronic music, because some people might find it more impersonal for various reasons, whether that’s because it’s not lyrics-based or explicitly narrative-based, there can be a problem of coming across as anonymous or losing some kind of emotional aspect to some people. I really struggle with electronic music that I feel lacks intent.

At the opposite end of that, I guess you also don’t want to resort to relying upon clichés to put across emotional intent?

CM: I made some of the tracks on the Whities record at around the same time as the UIQ one, and some sense of emotion seems to have been picked out from the Whities one whereas I think some of the reactions to the UIQ record suggested that it was more cold, industrial-sounding and fragmented. I did feel I was trying to move beyond that at that time, to put across some sincerity to what I doing but without making anything that sounded particularly saccharine. The Warp guys in the ‘90s managed to make very sincere music unintentionally. They were just guys making music and there wasn’t too much more to it at that time, but it was still very personal music. I can very much hear that in particular tracks, and I felt like that’s what I was trying to do with the Whities record; to marry this deconstructed and broken sound with something that’s more sincere and personal. Labels like PAN of course do something similar, and Arca is a good example of a producer doing that really well.

How did the Whities record come about?

CM: When we were doing some promotion for the Cong Burn Waves release, John [Howes] must have sent it to Nic [Tasker, Whities label head] and I introduced myself and got some thoughts back from him on it at that time, and he said to send some things over if I have anything to share. After that, the UIQ record happened, and I’d started making ‘Touch Absence’ around the time of preparing that record but I felt that it might not be a good fit because it was too club-orientated for UIQ. I made that unintentionally. I’d been in Manchester at one of the Meandyou nights, and usually [Meandyou residents] Andrew Lyster and Herron will DJ for a couple of nights whether it’s during the opening or closing. I’ve been at some of the nights where they’ll play records you won’t expect to hear like this old Mike Paradinas track called ‘Hi-Q’ which was quite a forgotten track of his. It was really percussive and urgent, but also super melodic. I think they played it at around 4am towards the end of the night and I just remember having a really euphoric moment on the dancefloor. I just thought that I wanted to make something that could create that feeling and that turned into ‘Touch Absence’.

It’s on the cusp of being quite saccharine or teary-eyed, so I was thinking it wouldn’t gel with everything else on the UIQ record. I was wondering where it might work, but then my mind turned to Whities because there’s been a lot of esoteric dance music of that kind on the label. Nic and I spent around a month going back and forth over email developing it because I sent the core sounds and structures, but he felt it was initially perhaps too dissimilar to some of my other work in that it didn’t immediately carry my sound. From there, we decided that would lead the record, and another two tracks followed it. It was initially going to be a three-track record, but I had this old orchestral-influenced piece [‘Voices Near The Hypocentre’] which I wasn’t too sure about initially. I doubted myself because I wondered if these orchestral sounds should work in what would otherwise be quite a contemporary deconstructed, experimental record. It felt like something of a statement though so I just worked on it more and incorporated some of the sounds on the other tracks into that so it all made sense as a whole.

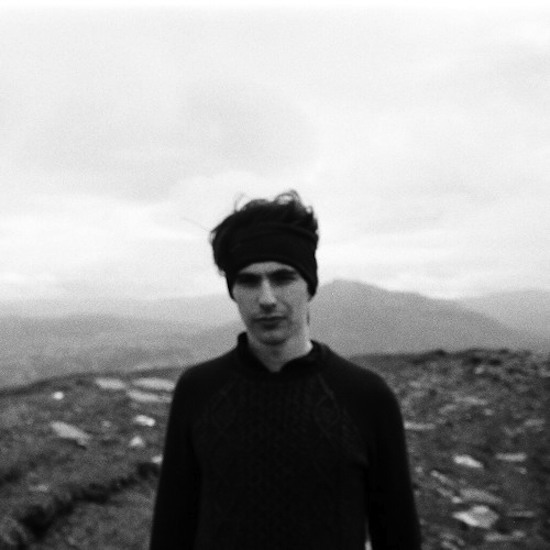

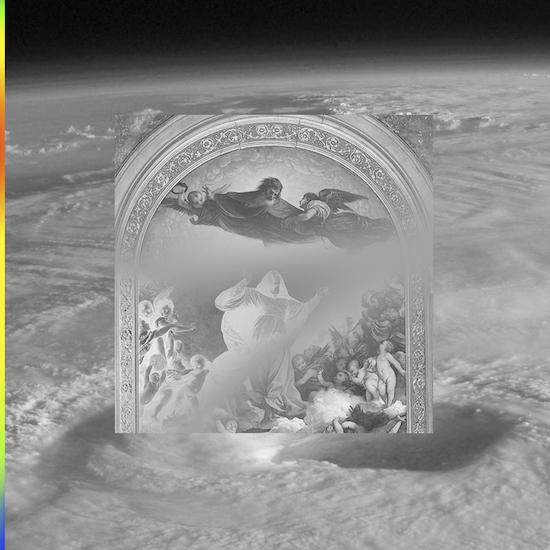

There’s a strong visual element tied in with this record too with the artwork and online promo, and I imagine this is the first time you’ve done something that extensive with one of your records, so how has that all come together with regards to combining the music and visuals?

CM We decided to do all that towards the end of last summer and by that point, the tracks were more or less finished with a few little changes being made. I travelled down to London to meet with Alex [McCullough, Whities in-house designer] and Nic and we got together for a few hours. All the ideas we had came together really easily. I had an idea of what I wanted the record to represent because I wanted it to avoid just being another esoteric electronic music record of the time with the predictable design of abstract shapes, because I thought that would be throwing away a good opportunity to do something different. Alex brought this idea to the table that when he listened to the tracks, they evoked this image of storms and hurricanes which I’d never considered. I thought it was great, but it was totally different to the kind of image I was having. He thought it would be interesting to combine that with what he described as a ‘youthful urgency’ that he could hear in the music.

We built this mythology around the record that I don’t want to go into in too much detail because I don’t want to run the risk of layering it in too much concept, but we used all this storm-based imagery and built this world around the tracks. I had these pieces of narrative that I used to write – not deliberately to accompany music – and thought could somehow come in handy one day, and we’ve used that for the record and included some on the back of the artwork. I don’t want to call it poetry though because I hate poetry. I think I’ll carry this through to other projects too, though maybe not necessarily with music releases, because I have other installation-based work going on.

Your music can alternate between some quite 4×4 moments like ‘Glasz’ and ‘Touch Absence’ and then obviously there are other tracks which aren’t quite on that tangent. Do you feel more comfortable producing in one way or the other?

CM: Those two tracks are maybe the only things I’ve made with a 4×4 structure, or that I’ve ever finished. It’s not that I don’t like making mixable or structured music, but rather when I try to do it, I find myself quite bored by what I’m doing. I don’t like to listen to music that is predictably going in a specific direction. I don’t really listen to a lot of traditionally structured dance music and I don’t mix music. All the mixes I’ve recorded have deliberately shied away from that because if I did record a mix like that, it would mostly be full of things I don’t listen to myself, not because I don’t enjoy it all, but it just doesn’t have the same sense of urgency to it to me as something where you can’t immediately predict the direction of where it’s going. It’s different of course if you’re in a club environment, but I don’t sit down with the intention of making structured music. I try to start in a position away from that and gravitate towards different time signatures and fluctuating tempos.

Whities 011 is out now digitally and on vinyl. You can scroll through the gallery just below to see more of Alex McCullough’s artwork for the release