Almost two years after its release, Kode9’s ‘Black Sun’ is still a somewhat mysterious track. Not literally – the 2009 single is a relatively simple formula of sharp rhythms, gridlike bass, smeared synth – but in the sense that there seems to be something located in its synthetic exotica that’s hard to fathom; a kind of drift that you catch and lose in equal measure while listening to it.

‘Black Sun’ reappears at the centre of this new album of the same name, the first full-length collaboration between Kode9 and MC Spaceape since 2006’s Memories Of The Future. It’s a new version that softens some of the bright edges of the original, introduces elements more gradually, and adds a layer of itchy, submerged crackle. The title, with its echoes of occultism and JG Ballard’s dystopian fiction, was apparently inspired in part by Kode9’s setting fire to copies of The Sun after the newspaper went on a spectacularly crass mission

to ‘expose’ the identity of Hyperdub artist Burial in 2008; with the album, it now also brings to mind a mutated solar body presiding over a suspicious Earth of false prophets, weird sex, physical trauma, uncertain bliss and scuttling and infectious beats. Contrasts and contradictions surface: one stand-out track, ‘The Cure’, is both abrupt and seductive; guest singer Cha Cha weaves a jazzy vocal line around Spaceape’s visceral, urgently delivered lyric and the stutters of drum and synth that come together for a collaged, unlikely refrain, spat out: “It’s like you’re waiting for a miracle to happen/It’s like you’re waiting for a universal pattern.” Lush, house-inflected ‘Love is the Drug’ whispers that it will “tighten round your neck”; the beatless hazes of ‘Hole in the Sky’ and ‘Othermen’ waver uneasily.

Writers like to slot narratives onto music, but in this case Kode9 and Spaceape have done it for us – Black Sun’s tracks form a story of post-nuclear survival, devised as a way of pulling together music written over a period of a few

years. “Having the story made it feel like a whole unit, and that helped us,” explains Stephen Gordon, aka Spaceape, as he and Steve Goodman (Kode9) outline a scenario where survivors choose either to take a drug (‘The Cure’) that’ll mutate them, but enable them to live on the irradiated Earth, or opt to remain fully human and therefore depart for what Goodman describes as a “monotheistic New Age Babylon” known as ‘Kryon’ – the title of the closing track, featuring Flying Lotus (and a place from which, says Gordon, “no-one’s ever come back…”)

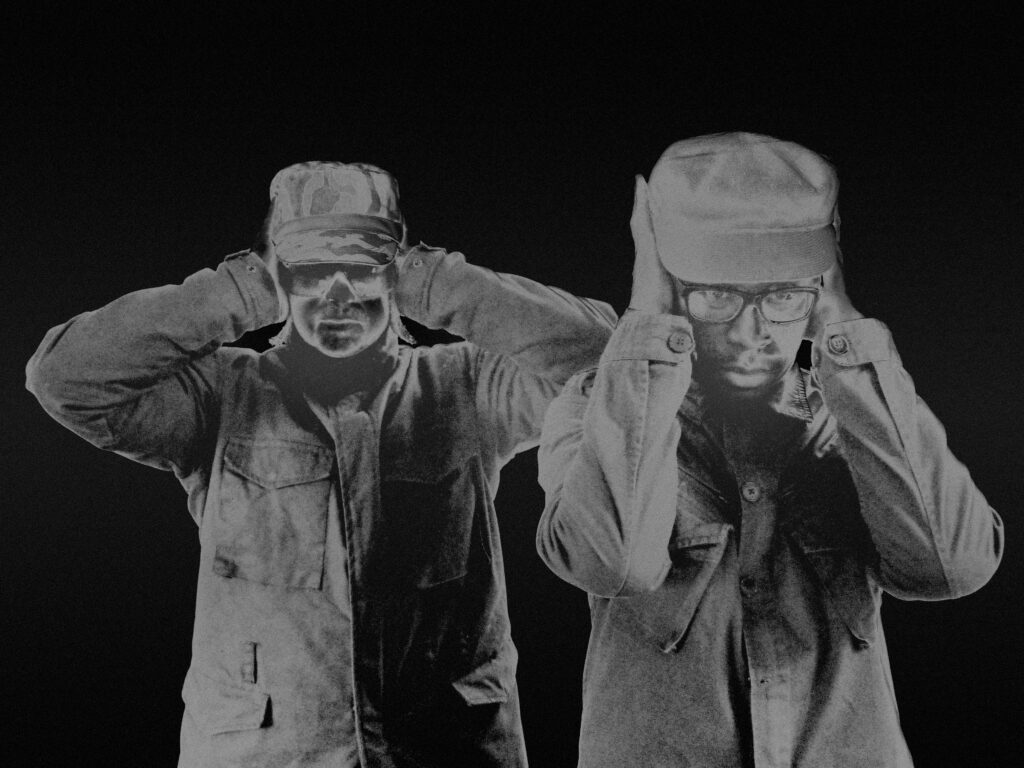

Cover artwork by Manuel Zambrano, inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, and a comic-strip interior by composer Raz Mesinai visualize the story, emphasizing that this is one of those meetings of music and SF that goes beyond just borrowing a few cool Bladerunner-ish tropes.

The half-decade since Memories Of The Future have been prolific ones for Kode9’s label Hyperdub, with 2009’s <a href="http://thequietus.com/

articles/03493-hyperdub-2010-a-state-of-the-bass-nation-address" target="out">Five Years Of… compilation confirming

how diverse and forward-thinking the label’s output has been, from the introspective soundworlds of Burial – whose new 12-inch is out this week – to the club success of producers like Joker and Zomby. It’s tempting to see the busy mood of Kode9’s first album-length work in a long time as indicative in some way of the proliferation of his label and its – his – relationship to the crowded, fast-moving flow of new music in 2011. But I think that belies how immersive and stand-alone Black Sun is – it’s not the murky bass bath of its predecessor, but instead something that works gradually on your surroundings, inviting the

listener to share Spaceape’s sense of the everyday “unreal”.

Some days it doesn’t take much to share that view. The day of my interview with the duo, the web is twitching with strange, bad news. Nate Dogg tributes line up alongside those to British MC Smiley Culture, whose violent death during a police raid is cloaked in suspicion. A nuclear reactor in Japan seems close to meltdown following earthquakes and a tsunami. An afternoon talking about paranoia, synthesizers, mutation and survival doesn’t seem all that odd.

How did Black Sun come together – when did it start making sense as a whole thing?

Kode9: We started it about four years ago, but it was only last summer when we tried to spend three or four days a week concentrating on it. Only then did it start to come together, although most of the tracks had been around in one shape

or another for a while. A year before that, we had pretty much the same album in place, but earlier versions, and it wasn’t gelling.

I think when you’re making an album, the key thing is that you get it all together and then you listen to it and listen to it and listen to it, and the stuff that makes you feel sick is the stuff that you have to deal with. You feel it physically, and then you just have to respond to that physiological reaction. You’re constantly trying to take out the bits that don’t make you feel good: it could be a bit of vocal or drum that repeats for five seconds too long, very subtle things.

Why make it an album?

K9: We like the challenge of making a long piece of work. I think our tracks work better in that context as opposed to big, anthemic singles – we’ve never really done that.

How do you work together on lyrics and music?

Spaceape: This album was different from the first, in many ways. The first album [2006’s Memories of the Future], I’d come in, lay down some lyrics and then I’d go; Steve would get on with it and he’d play me some stuff later. This one, we were both quite anal about getting things how we wanted them.

K9: When we record vocals, often they end up on tracks that they weren’t intended for. You listen to them, think, ‘that’s not working’, and try them on another track. It’s like a shifting jigsaw puzzle for a while.

SA: When we do our live set you might get the beat of one track and the lyrics of another and they cross over and drift around each other. We’re quite used to that, as opposed to going, ‘this lyric is for that track.’

There’s a lot of fragmentary vocals on the album – not just words but vocal textures, sounds chopping in and out, breathing…

K9: We did that much more on this album – multitracking the voice so he’s doing his own backing vocals, we’ve got Cha Cha doing backing vocals, and you’re also doing lots of vocal effects, to flesh it out.

SA: Yeah, breathing and all sorts of stuff, to make it sound more full, to give it a nice, round vocal sound with stuff coming from all angles. People are going to listen to this on headphones, and when you put your headphones on you want to

hear all that. We wanted to fill out those empty spaces with something.

It does feel more like it’s destined for that kind of personal listening than being played out.

K9: I think some of the tracks definitely are but, much more than the last album, some are much more upfront, aggressive, direct, immediate and work in, not necessarily a dancefloor context, but a live context. A live context tends to be somewhere between headphones and club. It varies so much – sometimes we’re put in the middle of a club to do a live set, which is not our favourite context, although we’re learning to deal with that. And last year we played at the Museum of Garden History, in a big church at Lambeth Palace, with everyone sitting on the floor. It was dark and the sound was quite strange and nice because it’s a church, and that’s definitely more towards the headphone experience – like the room was a big headphone that everyone was in.

With the lyrical themes on Black Sun, there seems to be a lot of fear going on. Where did that come from? There’s an atmosphere of not taking anything on face value…

SA: Well, that is true, because you’d be mad to anyway, right? And the things that interest me are the things that make life sometimes feel unreal. That’s what captures my imagination. For this album, some of the tracks were written in 2008 or 9, but then last year, I had a terrible year: I was quite ill, and what I was going through was also something that felt quite unreal, so I actually properly went over to the dark side… So some of the themes are definitely where I was at, there’s no doubt, ‘Black Smoke’ being one of them; ‘The Cure’ being another.

But the stuff that you do every day, there’s a surreal quality to it; it can have a dreamlike quality. As you said, you can’t take things at face value. It’s like looking through a prism, you know? You look, and you can see the outlines of things, but

there’s so many different variants of that one thing. Everything’s like that. That’s how I see it, anyway.

There are a lot of questions about reality, and what feels like a fictional view of things.

SA: From my experiences recently, it definitely felt like you were in some sort of sci-fi story.

K9: We finished the album and we wrote this fiction that encrypted our real experiences of the last few years into a science fiction-type story, and we had a friend make a graphic illustration of that into a comic strip. The whole story’s

about radioactivity and the artwork has a slight Japanese theme to it, and as things have been unfolding over the last week or so [the earthquake and subsequent nuclear accident in Japan] I’m just glad we didn’t do it in a jokey fashion. It’s based on real experiences, and as we fictionalized it I don’t think we

trivialized those themes.

But to do with going to the ‘dark side’, I think that when you tap into it, you shouldn’t be surprised when these things happen, because when you get down into that unconscious level things don’t have a past or a present or a future.

Everything that’s possible to happen that’s shit, is happening at the same time. So you’re obviously going to get these coincidences where, when you fictionalize something that seems dystopian, reality coincides at some point.

SA: It’s almost like reality catches up with it. Your unconscious is a place that’s active, really active.

The best science fiction is often the stuff that’s so prescient it almost feels like it’s happening now.

K9: it doesn’t have to be about something specifically; it’s loose enough to resonate in an open-ended way with things that are really going on in the world.

SA: Lyrically, I’ve always written in that kind of way – I’ve never written in a preachy, ‘this is how it is’ kind of way. It’s always open, because I don’t have an answer anyway. So I write what I perceive, and that then obviously leaves the door open for many takes on it.

How you realize these quite ambiguous ideas in sound?

K9: Generally we’re in the same headspace, so I can write music and he can write lyrics and they’re always going to be in a parallel mood. Most of the music I make is slightly downcast, melancholy or moody in one way or another – I’m not sure I’d call it dark, but it’s slightly moody.

We’re friends before we’re collaborators, so it’s quite a natural collaboration. I don’t have to change my sound too much to fit with his lyrics, and vice versa. [To Spaceape] You don’t really want to do party lyrics, or gunman lyrics, or jump-up

lyrics, so it’s quite unthinking in a way. We don’t have to force a convergence.

How did you meet Cha Cha and had you worked with her before?

K9: I met Cha Cha in Shanghai, where she lives, because I’d been out there to play. Her partner runs a venue called The Shelter, an old underground bomb shelter; I played there a few times and Cha Cha was MCing for me – she’s a soul and reggae vocalist – and a couple of years ago we went into the studio and recorded

backing vocals for a track called ‘Time Patrol’ that was on the Hyperdub compilation, and her voice complemented Stephen’s voice really well. I was out there in September after we had a good sketch of the album, we recorded on lots of different tracks and I came back with a pile of backing vocals. She ended up being the lead vocalist on ‘Love Is The Drug’, even though Stephen wrote the lyrics, because her voice fitted the track’s house style a bit more. Her vocals on ‘Black Smoke’ and ‘Neon Red Sign’ are very much backing vocals but she surprised us with ‘The Cure’ and did something much more than we expected.

I think the synergy between the two vocals on ‘The Cure’ is amazing; it’s totally different from anything I’ve done before.

SA: It’s mad because I’ve never met her!

Do you feel like she takes on a kind of persona for you, as another vocalist?

SA: In a way she does – it’s like we’re renegades and she’s got a shooter as well, and she’s got my back, do you know what I mean? That’s how I see her really. We’re both a couple of little sharp-shooters. She’s in the cartoon [in the album’s art-work] too.

K9: We’re all characters in this cartoon, and we’re all subject to the forces at play in the story, so whether she sounds like it or not, she’s part of the story: we’ve pulled her into this fictional world. She’s one of us.

So we’ve talked about some non-musical influences, but what do you think informs you, musically – in the sense that you’re MCing but with these narratives that are unusual to that style?

SA: I think it’s a bit from everywhere, and it’s all kind of mashed up into me. It’s a bit of soundsystem culture, it’s a bit of spoken word, it’s a bit of Prince, it’s a bit of George Clinton, it’s a bit of John Lydon in PiL, it’s a bit of Matt Johnson, it’s a bit of everything. It’s a bit of all the things I’ve really, really been interested in.

Sound-wise there’s a lot of analogue textures on the album, things that sound, if not old exactly, as if they have a feeling of memory and live circuitry – that’s interesting because we’ve been talking about a post-human society…

K9: The idea of the post-human future in what we’ve done is not necessarily a high-tech thing, it’s not like you become un-human because you become technologically upgraded with the latest gadgets, it’s more that your body starts to mutate. Parts of your body start to grow in a direction that makes you less or

more than human, or parasited by something that’s alien, and analogue synths for me have always been this quite alien type invasion of music, even when they’ve become familiar and people are doing pop songs or classical music – in the 60s and 70s people were playing Beethoven or Bach using synths, and that’s

a kind of domestication of this very alien, non-organic sound. But in this story, the synths kind of represent radioactivity. The rays of the black sun are basically what the synths function as.

SA: There’s also loads of crackle, lots of burning sounds.

K9: That’s because the Black Sun has scorched the earth and things are on fire. The crackle doesn’t represent anything – it’s just what it sounds like; it’s burning.

The first thing that a lot of people think when they hear crackle is vinyl, or tape.

K9: We’re used, over the last ten years, to people using vinyl crackle as an instrument to signify this lost world of organic sounds. That’s not what it is for us in the context of this album: it’s literally the sound of a scorched earth.

Do you feel to drawn to obsolete formats?

K9: Obviously Burial’s music is drenched in that mood. He uses crackle for a number of reasons, but one of them is this very emotional use of it to signify some kind of lost future. So yeah, I am drawn to it in certain contexts, but I’m not a crackle fetishist or an old format fetishist in the way some people are. I think part of the fetishisation of old formats is people trying to carve out a niche for themselves, and one way to do that in a very competitive world is to fetishise something that’s blatantly dying.

Anything that restricts your methods puts you in a niche or a bubble that for some people becomes like a marketing tool. As much as I love vinyl, what I can’t take sometimes – it’s the same with tapes – is the hypocrisy that goes along with your over-investment in an old format or dying format. Because I fetishise these [indicates synths] as much as anyone fetishises anything, but I’m not against soft-synths.

Do you you restrict yourself musically, in that you’re drawn to particular sounds?

K9: I think it would be impossible to do anything if you didn’t restrict yourself. There are so many options, choices, pre-sets in the software, pre-sets in the synths… that’s how you make things: you don’t start from a blank state, you eliminate options.

The track ‘Black Sun’ is like a kind of centerpiece of the album, isn’t it?

K9: It’s like a pivot round which the album turns.

Right, yeah, things are different after it.

K9: That’s exactly the story, in a way – even though the order of the tracks is a bit weird in relation to that idea, certainly on the album things sound different after ‘Black Sun’.

When it came out in 2009, it did feel like kind of a shift. Do you feel like it’s an important track for you?

K9: Yeah, it’s massively important for me, because it’s one of the few times I’ve had an idea in my head and then made it, and it sounds like what it sounded like in my head. Usually I have an idea, and it comes out and it sounds completely different, and for me, not as good as what it sounded like in my head. Whereas that came out pretty much fully formed. I find it quite a joyous track but some people find it quite painful and dark or, because of the dissonance, quite unsettling, and – I don’t know if screechy is the right word, but it’s a tone that’s

quite in your face. It’s not a mellow sound, especially when you hear it loud: it blares. And it was a threshold for me, one, because it came out fully formed and two, just because it was very different from what I’d made before: a lot more colourful, but kind of acidic in its colours. And, like in the story, things weren’t the same after I’d made it. Things sounded different to me.

Black Sun is out on Hyperdub now