The end, when it came, was little short of ignominious. Oh, they’d started out humbly enough – like a gangly, butterfingered baby – but they’d matured gracefully, growing into their once awkward body, blossoming seductively, before frustration, bitterness and hardship bloated their once elegant frame, their last words a sour, chagrined belch. Buried in an unmarked grave after a funeral which few attended, the only flowers by their headstone were rarely tended and soon withered. When the end came, Kitchens Of Distinction weren’t anyone’s prime candidates for resurrection.

But Kitchens Of Distinction always moved in mysterious ways. For starters, there’s that name, clunky and gauche. However much they may have tried to overshadow it with elaborate artwork, those three words were never likely to compete with having ‘Nirvana’ emblazoned across one’s chest. Then there were the lyrical themes that coursed through their work, their sometimes bespectacled singer’s lines at times extravagant, at other times stark, at all times thoughtful and poetic, his homosexuality laid bare. Even now, this might trouble some, but back when the band emerged in the mid to late 1980s, indie rock wasn’t used to ‘puffs’ behind a microphone, and the terrifying spectre of AIDS had polarized peoples views on homosexuality to a painful degree.

The band, furthermore, were not averse to donning dresses, both in their videos and on stage, and rarely took interviews seriously. And, of course, there were the bad decisions, the bad timing, and bad luck too, some of it needless, some inevitable, all of it ultimately contributing to the decline of a band whose debut album was released the same week as The Stone Roses’ to better reviews.

Would-have-beens? Could-have-beens? Should-have-beens? For a long time, no one even asked. This is why it’s so surprising that, twenty seven years after their debut single, ‘Last Gasp Death Shuffle’ (an inauspicious 7” whose A-side was sung by a guitarist who would never venture in front of the microphone again), and seventeen years after their swansong single (confirmation that their spirit was extinguished), they decided to reanimate the corpse they’d abandoned. Against their better judgement, Kitchens Of Distinction – the ‘shoegazers’ who stared at the stars, the ‘dream-pop’ moment that pop historians slept through, the architects of ‘sonic cathedrals’ left to crumble – have returned to life.

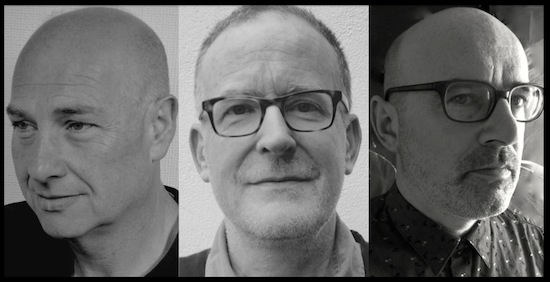

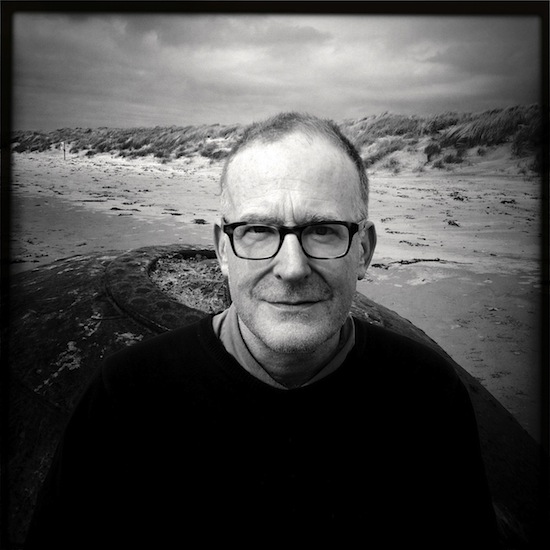

A little less than twenty years since their last album, singer/ bassist Patrick Fitzgerald and guitarist Julian Swales settle down in a café at the front of London’s Tate Britain. Third band member, drummer Dan Goodwin, is also part of their rebirth, though “he’s not as involved,” Fitzgerald clarifies, “and so not as involved in the promo for it.” But, he’s keen to point out, “We sorted out our past aches and pains into reasonable order a couple of years ago before this record came into being.”

They’re here to talk about their fifth album. It’s one they never meant to make. For an hour and a half, they smile and sigh at the recollection of how they got here, responding amiably to the idea that they were one of those bands who might have fared better had the dice rolled more favourably, accepting their fate with a good humoured grace. Afterwards, Patrick will wander through the nearby gallery admiring L.S. Lowry’s paintings, exhibiting an enviable knowledge of both the painter’s more obscure works and his influences, before heading back to his home near Manchester. Julian, meanwhile, will head to Islington for a couple of pints with a friend, then take the train to rejoin his family in Brighton. Cruelly, however, the recording of their first face-to-face interview together in almost two decades will quite simply, inexplicably, self-destruct. Some might consider this typical for Kitchens Of Distinction.

One week later they’re on the phone. If they’re irritated at having to repeat the procedure, there’s no evidence of it at all. “These things are sent to challenge and see how strong we are as people,” Fitzgerald laughs.

“It’s fine to do it again," Swales agrees. “If it had been horrifying, I’d have found an excuse not to.”

Their words are equally applicable to the fact that their band has, in a loose sense, reformed. That the reformation is loose refers both to its unplanned genesis and its studio-bound status.

“I never really wanted to get Kitchens back together again,” Swales admits, “and nor did Patrick. Nor did anybody want us to get back together, I think! And then we sort of ended up doing it. That it’s happening at all is rather odd. It’s almost like it’s a dream.”

Naturally, neither of them had given up on music altogether since the band split in 1996. Fitzgerald had retrained as a doctor – he’d quit earlier to pursue the band’s fortunes – before suffering a period of poor health that led to a kidney transplant in 2008. But he’d worked on other, admittedly lower-key – if unintentionally so – projects: one album with Fruit, with guests David McAlmont, Miki Berenyi (of Lush) and Isabel Monteiro (of Drugstore); Lost Girls, with 4AD signing Heidi Berry, though their album remains unreleased; and Stephen Hero, a solo project that he only wound up at the end of the last decade after three albums and two lengthy EPs, and which was arguably his most successful venture since Kitchens. Swales, meanwhile, provided music for TV and theatre, and at times contributed to his former colleague’s ventures. “We hadn’t fallen out,” Fitzgerald emphasises. “We were all friends, but it was never like it was in Kitchens, where it was a life or death thing for him”. All the same, an attempt to work together more formally at Fitzgerald’s Salford studios in 2007 proved, the singer says, “sad, and not good”.

“But,” Fitzgerald continues, “we continued talking, and each time he was in Manchester we’d meet up and have a few drinks and a chat. And then I had some new music that I wanted to play him, ‘cos I wanted to see what he thought, and that seemed to spark something inside him. So in 2011 he came up here and started doing some music without any sort of goal, and we just carried on like that for about six months, to-ing and fro-ing, coming up with bits of music, and then they shaped into songs. And that took about three years. And I think I said to Julian, ‘What are we going to call this?’ and he said, ‘Well, we should call it Kitchens Of Distinction, because that’s what it is.’ And I think that was the length of the conversation. I’d been umm-ing and ah-ing about the whole thing for quite a long time: ‘What is this? What are we making? This might be a really stupid thing to do. This might be a really wise thing to do. Do we have a choice? Because if we’re going to call it something else, why would we do that, and what is Kitchens Of Distinction?’ But that’s what it is.”

And what that is, fans will be delighted to learn, is the album that Kitchens Of Distinction promised but never delivered back in the mid 1990s. What that means to newcomers is ten songs of unusually notable literacy and forty two minutes of sparkling, cascading guitars whose mood perfectly, intuitively matches each track’s lyrical content. It’s called Folly, and the title is appropriate for a number of reasons.

“After I did my last [Stephen Hero] record [2009’s Apparition In The Woods],” Fitzgerald elaborates, “I didn’t want to do stuff on my own, but I really, really didn’t think this would be an appropriate thing to do. I’d seen so many people do things like it and thought, ‘Ooh, ooh, folly! Absolute folly!’”

But there’s more to the name than that, he expands. “It’s part of a Tolstoy quote from War And Peace,” he continues. “‘Seize the moments of happiness, love and be loved! That is the only reality in the world, all else is folly.’ And the other thing, of course, is the madness of British people making stupid things in their garden: ‘follies’. I think that was a very British thing to do, you know? So we’ve made a folly. We’ve made a thing that’s quite useless, but quite pretty. I just think it’s a really apt title. I’ve no problem with it being madness or daftness, because I still think what we’ve made is rather beautiful.”

Once again, Fitzgerald is being modest. Folly is neither daft nor mad, and is up there with the best of Kitchens Of Distinctions’ work, a catalogue that was first opened at the end of 1987 with that unconvincing, self-released debut single. It was, they now reveal, one of fate’s more fortuitous twists that saved them from pursuing that particular musical path and sent them on a more picturesque journey.

“I had lots of gear nicked from the place I was staying,” Swales recalls, “which was Patrick’s house. Maybe he nicked it. I never thought of that! But it all got nicked, so I got the insurance money, and then I went to buy some more bits and pieces. And at the time I was really into The Cocteau Twins, and A.R. Kane – who were mates – and I was really influenced by what they were doing. If I hadn’t have had that stuff nicked we might have turned into a thrash metal band. Which means we probably would have been successful!”

With his new toys, Swales built on the eddying sounds of his influences, presaging the phantasmagorical approach of bands like Ride and Slowdive while Fitzgerald delivered astute, candid stories in his articulate, passionate manner. Many songs on their debut album, Love Is Hell, released by One Little Indian in 1989, were focused on the more mundane qualities of human relationships, while ‘Margaret’s Injection’ made no secret of the singer’s hatred for the country’s prime minister: “I wish I’d killed you more/ Pain is your just reward”. (These days his distaste for The Iron Lady hasn’t softened: “They’re going to build a statue of her,” he gasps. “I can’t abide anything to do with her. I can’t even say her name, actually. Let’s move on. Dark, bad times…)

But though Fitzgerald’s vocabulary appeared unusually cultivated, unafraid of employing compelling imagery and sharp wordplay – “Here sings the innocent/ He’s turning water into brine” – it was flirtatiously frank lines like “I open my eyes and look at his face again/ Oh, good God, so nothing’s changed” and “I am the sinner with only socks on” that were noticed by the media, distracting from the band’s musical achievements.

“I’m useless at lying,” Fitzgerald sighs. “I can just not say something, but I can’t lie. In our first NME interview with David Quantick, he said, ‘Do you want people to know about it?’ And I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ I had no bloody idea. I thought everyone was over that. I really didn’t have a clue. It didn’t actually occur to me that it would be a problem.”

But, nonetheless, Fitzgerald had an agenda of sorts. “It was all post-AIDS and Thatcher when this was going on, and it seemed very important to be outspoken. But it become an issue, because the band got labelled as a gay band, which of course didn’t go down too well with Dan and Julian for various reasons, because it seemed to misrepresent them. It also became an issue because it wasn’t about the music and the songs, which is what our passion was. It became a hurdle to jump over before you could enjoy the music. In The Simpsons there’s the episode with John Waters, and Homer says, ‘I like my beer cold, my TV loud, and my homosexuals flaming.’ And I think ‘ordinary bloke singing in band, happens to be a nonce’, it was a bit, ‘What? Eh?’ In the way that The Smiths were quite digestible, I don’t think we were. It was boys’ music with this poof in it, and how can you have that? That’s a bit weird.”

“It did feel a bit odd at times,” Swales concedes, “and a bit annoying. But that’s the press for you. They’ll find anything easy to latch on to. If the fact that Patrick is gay had made us hugely successful I’d have had a different opinion of it. But you know: what can you do? I’m sure that one day it will not even be mentioned at all. But that’s probably a long way off.”

However it affected them in the long term, the album’s impressive sonic universe – like an otherworldly Chameleons, had they been produced by Martin Hannett (with whom, coincidentally, Kitchens would soon try, unsuccessfully, to work) – saw them championed by enough members of the media to win them a licensing deal from A&M in the US for their second album, Strange Free World. They hooked up with producer Hugh Jones [Echo And The Bunnymen, The Icicle Works], and the results were a dramatic expansion of the Kitchens sound.

“We didn’t know what we were doing on the first album,” Swales confides. “The drums were programmed. We only had a certain amount of time to do it. And then on the second one it was a whole different story. I had such a great time with Hugh in the studio. To have somebody there who’s more into it than you are is fantastic. I don’t know if he was into it more than me – he probably wasn’t! – but he certainly knew what he was doing more, and how to get me to achieve more and make what I was doing sound better. It was a fantastic time, recording that album. It was probably one of my favourite periods in my life.”

With its pristine, rich, cinematic sound, 1991’s Strange Free World found Swales’ guitars sounding more crystalline than ever, fooling some critics into believing that much of it was performed with synthesisers. Its artfully textured surfaces, alongside Fitzgerald’s growing confidence as a lyricist and singer, enabled the album to graze the UK charts – it peaked at 46 – and also earned them an American audience on the back of college radio support for singles ‘Drive That Fast’ and ‘Quick As Rainbows’. A follow-up a year later, The Death Of Cool,

again produced by Hugh Jones, refined their aesthetic further: the swirling ‘Mad As Snow’ provided a bridge between Fitzgerald’s especially poignant ‘On Tooting Broadway Station’, a song which reflected a sensitive, painfully honest side to his character, and the maelstrom of Swales’ guitars on the ferocious ‘Blue Pedal’.

Though some consider it to be their masterpiece, Swales is less convinced. “I was miserable about various things that were going on in my life,” he says, “and we used Hugh again. I don’t think that was the right thing to do, because there were no surprises. We were just doing the same thing. We knew all his tricks, he knew all ours, and we should have got a different producer. But we were playing safe.”

In America, too, the response was not as enthusiastic as A&M had hoped. Desperate to ensure they reach a larger audience, the major label sent them off on tour with Suzanne Vega, the memory of which provokes both laughter and despair.

“I would have preferred to do the Lollapalooza tour,” Swales chuckles wryly, “but nobody asked us. I think in my heart I thought we were reaching the end of some kind of thing with A&M. ‘Let’s do it, because otherwise we’re not going to tour at all.’ We made a lot of mistakes that, with hindsight, it’s easy to say, but obviously touring with Suzanne Vega was a complete waste of time, and a disaster from start to finish. It makes you think, ‘What on earth were they thinking, putting us on the bill with her?’ We were a loud band. She was just soft rock. It was completely misguided.”

“In California,” Fitzgerald adds, “she was booked into these supper clubs where you eat first and then see the band. Nice idea, but we’d play while they ate! I remember her coming up to me saying, ‘What’s that song you play?’ and it was ‘Mad As Snow’, and of course it had a quiet start. She went, ‘Have you got any more like that one?’ Ah, bless her. Poor thing.“

From there it was all downhill. Their fourth album, Cowboys And Aliens, was initially rejected by their labels, and, when it finally saw the day in late 1994, its cover was emblematic of their disintegrating state. Compared to the sumptuous, elaborate imagery that had graced their first three records, this looked like a demo, an awkward, blurred snapshot slapped lazily against an unimaginative blue background that clearly still embarrasses them today.

“It’s a shocking cover,” Fitzgerald groans, “and that’s the result of three people not being able to speak to together or make a decision properly, so what you end up with is bad art, as ever. And there it is, on full display to the world. I can remember someone at the record company sending us a knocked up sleeve: photos of us, and someone had drawn antlers coming off our heads to look like quasi aliens. Yeah. That’s how bad things had got. And it all just became too difficult for me to be a person in that unit. You couldn’t do shit because everybody was in such a bad mood, frankly!”

Far from all of Cowboys And Aliens is poor. Opening track ‘Sand On Fire’ exhibited a tremendous confidence that denied the troubles behind the scenes, while closer ‘Prince Of Mars’ shivered, shimmered and finally exploded in a way that reflects Swales’ recollection that the recording sessions were “a good experience, one of my favourites.” But too much of the album is forgettable, and though Fitzgerald declares the late addition to the album of ‘Come On Now’ to be one of the band’s crowning achievements – “Having had the album rejected by A&M in America, so therefore by One Little Indian, that was us coming up with a song saying ‘Fuck you!’, and not only that, but putting strings on it, which was a very velvet gloved ‘Fuck You’! – it sounded overall like a pale shadow of the band. Too much of Swales’ work was, by his standards, conventional, and then there were the backing vocals that popped up, as welcome as a jack-in-the-box at a funeral, on ‘Remember Me’ and ‘Now It’s Time To Say Goodbye’, a song which faded out unceremoniously like it had been callously built for radio (as it most probably had been). And though ‘One Of Those Sometimes Is Now’ broke into a blizzard of hazy effects, it was more akin to the murky sludge of Swervedriver than the blissful noises with which we were familiar. As for the acoustic guitar at its beginning – evidence of Fitzgerald’s growing interest in more traditional songwriting – it felt, to be blunt, wrong, almost like a betrayal.

And then?

“And then,” Swales states calmly, “there was nothing. It was like the cupboard was bare. We’d done everything we could, and there was nothing to follow.”

That’s not entirely true. Kitchens Of Distinction took another year to decay, their corpse twitching in 1995 with a well-intentioned contribution to 1995’s The Disagreement Of The People – A Collection Of Artists Against The Criminal INjustice Act – ‘Pastor Niemöller’s Lament (Never Again)’ – and a final, depleted wheeze, ‘Feel My Genie’.

It was not a noble conclusion.

“If the paper wasn’t so bloody wet from crying,” Fitzgerald grins, “I might write it all down. But if I’m going to blame anyone, I’m going to blame ourselves for making terrible decisions as we went along. I think we were the most unhelpful band to work with, given that we christened ourselves what we christened ourselves. Start from there! We were so uncompromising. There were things we didn’t have control over, but not that many. And I think signing to One Little Indian was the stupidest thing to have done, but hey! Someone offered us a deal and we took it.”

There’s a long, pregnant silence when he’s asked to elaborate, as he weighs up how to illustrate the kinds of issues they faced with the label. In the past, he’s not pulled his punches on the subject, as an early B-side, ‘Anvil Dub’, proved, using as its lyrics some of the phrases that the company’s staff had employed during phone calls: “It’s your money”; “It’s up to you, mate”; “Music makes money”…

“What can I say?” he finally shrugs. “Bless them for letting us make records and putting them out. They managed not to fuck that up totally. The entertaining thing I always found was, we got the vinyl for Love Is Hell, and it had three pieces of classical music on it. So that’s kind of what you’re dealing with…”

Both he and Swales remain philosophical about how things panned out. Though support was never universal – even John Peel remained reserved about the band, only offering one session, in 1992 – there was enough praise over the years, and enough hype in the US, to raise expectations. Somehow, however, the trio never caught the wave that so often seemed within their reach.

“Sometimes I think, ‘My God, we got away with it, didn’t we? For quite a few years!’” Swales maintains. “Other times I think of wasted opportunities. And whenever I’ve ever read anything about the band, or talked to people, they’ve always said ‘You should have been bigger, you should have made it’. So that has an effect on you. Do you remember Bruce Forsyth from The Generation Game? He’d say, ‘Didn’t he do well?’ That’s what we were. They’d bring some expert on, and we were one of the contestants at the potter’s wheel, and we did quite well and got seven out of ten. But it’s just daydreaming when you think about those things. What happened happened, and it’s done, and now I think about the present as much as I can.”

Fitzgerald’s similarly minded, and maybe even more positive about their experiences: "The fact that [the albums] didn’t sell hundreds of thousands – though they did sell quite a lot – those factors I probably have very little control over. I think we succeeded and did what we wanted to do. The fact that it wasn’t hugely successful in commercial terms doesn’t matter. It was hugely successful in artistic terms, I think. From my point of view, I can look at those records and go, ‘Yeah, they’re alright. I don’t feel shame!’ Whereas if I’d been in Bros I might feel shame! Look at Hugo Largo: God, they made amazing records! And not many people know them, yet artistically those are stunning, you know?”

“We didn’t want to go on Top Of The Pops,” Swales reiterates. “We didn’t want to have success. We just wanted to do our own thing. And then the pressure comes on you to do well, and suddenly it’s a business.”

This time, with Folly, they’re keeping a far tighter rein on its release and, at the same time, lowering their expectations. They have other things to worry about, after all: Fitzgerald still works as a doctor, while Swales continues to work to commission and take care of his family and kids. The band’s not a priority, and they’re not ashamed to say it never has been since work on this record began. But perhaps that’s what makes Folly such a joy: they’ve been liberated from the commercial demands that once weighed upon them, and its creation was undertaken with no specific goal in mind.

“I think if it had have been calculated, it would have been a disaster,” Fitzgerald agrees. “An unmitigated disaster. Because we would have been so desperate to try and redo what we did before.”

Instead, it’s music made for the purest of intentions, and all the better for it. It may even offer some of the band’s most powerful and musically courageous work by featuring some of Fitzgerald’s most ambitious lyrics to date while refusing to depend upon Swale’s effects pedals for its impact. ‘Extravagance’, for instance, recalls Cowboys And Aliens’ highlight, ‘Sand On Fire’, its subject – the Marchesa Luisa Casati, an Italian heiress, socialite, and muse to the likes of Cecil Beaton and Jean Cocteau – vividly described in a fashion that outclasses even Neil Tennant’s attempts at capturing his beloved, exaggerated demi-monde: “Who dares walk her cheetahs on the dark canals of Venice?/ Diamond leashes glitter, servant flames splutter/ Emaciated spectre with kohl tattooed eyes." Meanwhile, the chilling ‘Photographing Rain’ – which, unusually for Kitchens, employs a piano, but compensates for that with, they claim, fifty tracks of guitar – was inspired by a famous photo said to be of two gay Iranians who’d been hanged from a crane, and finds Fitzgerald typically unafraid of addressing a subject that ought, in the 21st Century, to be far less controversial.

Recent single, ‘Jupiter To Japan’, is of course considerably more joyful, its subject and arrangements a nostalgic recollection of the glamour of the Bowie-influenced 1970s – “Hanging out at Eric’s/ In cobwebbed frilly sleeves/ Dressed roughly as Victorians/ Dressed drastically as queens” – and ‘I Wish It Would Snow’ sounds like it could have fitted snugly on Strange Free World, its maudlin regret at the humdrum necessities of everyday life easily recognisable and touchingly expressed. Another highlight is ‘Tiny Moments, Tiny Omens’, whose title alone summarises one of Fitzgerald’s lyrical skills. It was inspired by Melvyn Bragg’s interview with playwright Dennis Potter shortly before the latter’s death, and captures the bittersweet wonder of knowing that one is seeing things for the very last time. Amidst yet another of Swales’ luminous performances, Fitzgerald sings of how he’s “not ready yet to forget/ Burnt out cars on Brixton Hill/ Francis at the Apollo/ ‘Ghost Town’ on the radio”.

Given the sense of human frailty and mortality that runs throughout Folly, it’s hard not to suggest that Fitzgerald’s own recent health issues may have informed his approach to the album. As conversations with him tend to, the question provokes an optimistic response.

“I think it’s actually informed a lot of my life,” he expounds, “because I knew it was coming. That’s the interesting bit for me. What happened was my Mum got sick many years ago, and I ended up getting a scan – because it’s a hereditary disease – to see whether I’d get it, and when I was about 19 I found out I would. And so it became apparent that I needed to do the things I wanted to do soon. I quit being a doctor and joined a rock band because I could. In my head there was no problem with that, because life might be short. And then it did happen: I got sick in 2006, and in 2008 I had a kidney transplant. I’m well now, and I have to say thank you so much to the family who allowed me to receive that kidney, because that changed my life and gave me joy again, even if it might not sound like it on the record. But it absolutely did.”

Such a sense of contented acceptance is evident in the album’s final track, the hymnal ‘The Most Beautiful Day’. But it’s the opening song, ‘Oak Tree’, that is the Folly’s true standout. An absorbing waltz swathed in Swales’ trademark radiance, it’s a deeply moving paean to the abiding nature of true love. It’s especially timely given ongoing resistance worldwide to the idea that fidelity and loyalty within a homosexual relationship are deserving of formal legal approval. It also boasts some of Fitzgerald’s most striking lyrics to date, journeying from the outstanding rhyme of “In our bed of deep mahogany/ We fucked about, kissing and sodomy” to the onset of ill health in later years – “Suddenly organs were failing/ I bought salves, grapes/ And mostly, I suppose, I stayed” – to the relationship’s inevitable, sorrowful end: “Under an old apple tree/ I scattered his dead body/ To feed the orchard again/ A rich source of calcium/ And my tears.”

“When people write about love,” Fitzgerald says of his motivation, “they usually write about the moment of falling in love. And what they don’t often write about is the actual length of love until death, of actually living with someone, loving them until the bitter end. It was about celebrating two men living their life together, from the dirty mucking about to the reality of ill health, and having to look after each other as things inevitably fall apart.”

After a two decade break, it now turns out that the loyalty that Fitzgerald, Swales and the absent Goodwin share is comparable. As Fitzgerald sings in ‘Oak Tree’, “Despite the removal of hope/ Despite the worsening/ We stuck through it”. That their band’s reawakening seems to have been warmly received so far must feel like vindication after the disappointments and traumas they endured first time around. It’s also vindication for their fans, who watched their grim, slow journey from distinction to extinction and yet held true to the idea that the band had made some of the most treasurable music of that generation.

“If people are warm to us,” Swales says cheerfully, “I think that’s lovely. But the intention behind the music is warm, so it should be greeted with warmth. The fact that we might not have had wide success may be helpful to that. I remember telling somebody about Arcade Fire years ago, saying ‘Listen to this, it’s amazing’, and a couple of years later they’re playing stadiums and I feel like, ‘Oh, I can’t tell anyone about them anymore. They’re not as special as they were.’ I know that’s quite a cliché. Only a few people had heard of them and now everybody knows them, so they’re not your private possession any more. But we still are!”

History rarely gets to be rewritten, but it seems that Kitchens Of Distinction may at least succeed in adding a new chapter to their tale. Having said that, there now seems to be some doubt as to whether Folly will be their last stand after all.

“I thought this record might be a full stop” Fitzgerald acknowledges, “but now I think it might be a semicolon. The creative juices in Julian seem to be happening again. I think this has switched him on a bit. He now realises that this might be quite gratifying to do.”

“I’ve noticed that I’m picking up the guitar more,” Swales confirms. “I’m coming up with ideas and thinking, ‘Ooh, this is a bit Kitchens-y.’”

Whatever happens, wherever this may lead, “it is,” Fitzgerald concludes, “a much more graceful ending…”

Folly is released by 3Loop Music on September 30