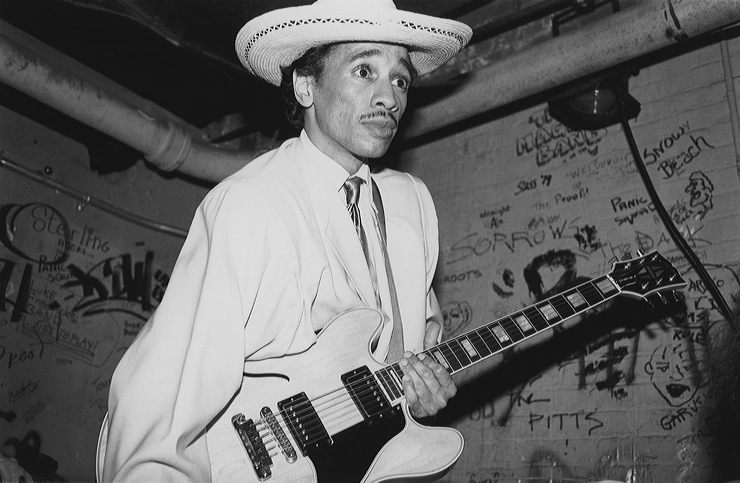

When you go to meet, say, Wild Beasts, lovely as they are, they look pretty much like you and me. August Darnell, however, looks like Kid Creole – in other words, a proper pop star, someone beamed in from somewhere rather more glittery than here. He looks fantastic for someone who recently celebrated his 61st birthday. At its best, I Wake Up Screaming – the first Kid Creole studio album for 14-years, released on Strut (home of the great Disco Not Disco and Horse Meat Disco compilations, Mulatu Astatke and Ze Records reissues) – is as suave, strange and singular as anything he’s done. Certainly it’s way better than it has any right to be: collaborating with Andy Butler of Hercules & Love Affair (particularly in evidence on the giddy pulse of lead single ‘I Do Believe’) was an inspired idea, and Darnell seem reinvigorated by the process. He’s funny, sharp and talks at a hundred miles an hour.

With his brother, Stony Browder Jr, Darnell formed Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band in the mid-70s, and had a hit almost immediately with the slinky, subversive big band/disco hybrid ‘Cherchez La Femme’. Hugely underrated as a lyricist (who else would write pop songs about being unable to get it up, disowning a child, or use the word ‘slut’ in a chorus?), his string of hits with his own band, Kid Creole and the Coconuts, in the early Eighties – as well as the fruits of his stint as in-house producer at Ze Records – still sound brilliantly bizarre. In other times, Darnell might have been called a wit; his best songs are dazzlingly witty: they can also be sarcastic, ambiguous, deceptively eager to please. It’s pop as a moving target, brighty-coloured – even garish, but rich with shades of grey.

Tell me about being a child in the Bronx in the Fifties and Sixties.

August Darnell: Oh the Bronx man! Jesus Christ! You know what? The Bronx has a bad reputation because people associate it with drugs and crime and prostitution. But as a child you don’t see any of that. As a child that’s your only world, all you know is that one neighbourhood. It was a great place to grow up because it was full of every ethnic group known to mankind, and as a result you hear every kind of music. You heard salsa for sure, because there was a large Puerto Rican contingent, you heard European music – there were Italian families, Irish, the Jewish communities. But you also heard a whole lot of r&b, a whole lot of funk – you heard James Brown, you heard Wilson Pickett – but you also had the Caribbean families, so you heard calypso and reggae. Without ever travelling I was a traveller. I learnt at an early age that one ethnic group is not better than another, which is an amazing thing to learn [young]. It wasn’t until I became a teenager that I started seeing things, and learnt that the Bronx is a dangerous place. You’d hear of stabbings, or someone got run down, or someone did a bad drug deal. But you find that in any neighbourhood. I think the Bronx was a solid, solid foundation that got me started, as James Brown would say, on the good foot.

When I was old enough I moved to Manhattan – once you had the Bronx foundation nothing could frighten you in any way. There was so much ambition in Manhattan. The Bronx was all about survival technique: you survive the Bronx you get on to the next level in the board game. Manhattan was all about creativity. It was a community of spirit, a camaraderie. Those early days were great. Fortunately I had a brother who was a musician who taught me everything there was to know about music. He was formally trained, I was not – I was trained by him. I would not have gone into music without him; my brother’s influence was almighty.

[Stony] was the bohemian, the one who set the standard for how you’re supposed to be living your life. Not waking up in the morning, not grading papers – cos I was a schoolteacher, I went off to do the legit thing, pursue a job…

You went to drama school though…

AD: Yes. Majored in drama with a minor in English. But then when the draft – the Vietnam war – came along, I switched majors ‘cos they looked at drama majors as frivolous people who didn’t know what to do with their lives so they were being drafted left, right and centre. I didn’t want to go to Vietnam [broad grin]. Wonder why?! So I switched major to English, because that was regarded as respectable, and there was a shortage of English teachers … But my brother went to the draft board and pretended to be crazy, and pulled it off. I couldn’t – and I’m supposed to be the actor in the family. That is how we pursued our dream of succeeding in the music world. We survived the Bronx and we survived Manhattan, and Manhattan gave us everything we need in terms of contacts.

Stony was very lucky in that the girl that he dated was one of the greatest singers to come along, in my opinion – Cory Daye. She was influenced by the greats – Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and took it to a whole new level. Without Cory we’d have never broken that boundary and gotten to that pop music thing. People loved that voice – it was so recognisable. Magnificent. We were born under a lucky star.

AD: The first song on the new album is ‘Stony and Cory,’ cos they’re the greatest influences in my life. I should have tackled that subject years ago, when I had my greatest success with ‘Tropical Gangsters’. Of course, I got more successful than Cory Daye, than my brother – but those are the people that made me what I am. Cory Daye taught me every thing possible about being a lead singer, in terms of putting your stamp on a song, so people immediately know ‘That’s Cory Daye.’ In the early days I used to sing with a fake island accent, ‘cos I wanted Kid Creole to be this character from the islands – it was only later I developed my own style. I never looked upon myself as a singers’ singer. I know guys in the Bronx who were fantastic singers but they never got out of the Bronx.

My brother and I had the traditional sibling rivalry. When I split from the Savannah Band, I could have fallen on my face, but I got lucky. The talent I did have was in perseverance. The first Kid Creole album sold about five copies, that could have been the end of it right there. Fresh Fruit in Foreign Places sold seven copies – that could have been the end also. But I had that stubbornness. I had to prove to my brother that I could do it. When I jumped ship form the Savannah band, Cory asked me who was gonna be the lead singer, and I said I was. She laughed in my face! [broad grin] I’ll never forget that! I’m the kinda guy that if you tell me something’s not gonna happen I’ll keep trying ‘til I drop dead. But there was luck too. It was luck that the British entrepreneur Michael Zilkha [of Ze Records] found us, it was luck that Seymour Stein signed us [to Sire in the States], it was luck Chris Blackwell found us in Europe, it was luck Tommy Mottola was our manager. I had all these giants around me. I knew people who would cut off their right hand to have Tommy Mottola as a manager then – he was the Savannah Band’s first manager. We were lucky sons of bitches, having come from the Bronx with nothing.

The Savannah Band albums haven’t been reissued properly, have they?

AD: No. they should be. They’re timeless. I always hold up that first album as the ideal of what I’d like to achieve. I don’t think any Kid Creole album comes close apart from this latest one. The first Savannah Band record was pure magic. The reason: we were twenty-something-years old when we made it, 1976, and we had stored up ten-years of writing – we started young. You had a lot of songs so you picked the best. Ten years of frustration built up and it’s like BOOM! I think it’s only nine tracks. That album opened doors for us for the rest of our lives. It was new. It was innovative thanks to my brother, who said: ‘I’m gonna take from the past – because I love Duke Ellington and the Dorsey brothers, Tommy and Jimmy, and I love Frank Sinatra’s crooning and Ella Fitzgerald. I’m’a take all that shit that I love and take it to a new market, a dance market ‘cos disco was god then, I’m’a put a beat on it [mimics hi-hat] Tsss-Tsss-Tsss.’

[link to Duke Ellington Big Band, ‘43]

But it wasn’t straight disco, was it? I mean, have you ever done a record that was straight anything?

AD: Mmm-mm. Exactly! I’m glad you said that because I always said you won’t ever find any pure music in Kid Creole. Nothing pure about it. I call it mongrel music. That’s what makes it exciting to me. Our strength is in the combination of borrowing a little from the calypso world, borrowing from the Four Tops and the Temptations and borrowing heavily from James Brown and putting it all together into this concoction. The use of horns is all based on Tito Puente and my love of the salsa arts – but it’s also based on those close harmonies from the Forties, on Duke Ellington’s arrangements and all of that great stuff that you hear in those old records.

The great Charlie Calello, who’d produced Laura Nyro, produced the Savannah band.

AD: Great guy. He also did a stint in the Four Seasons. You don’t know anything about the Charlie Callellos of this world as a young guy until someone brings them to you. Wow. Charlie Callello?! Recently I was in Iskia for the Film Festival there, and I met one of my idols – Mike Stoller from Leiber & Stoller. I said, ‘Wow, Mike, you have no idea how much you’ve influenced me.’ And he said ‘I know.’ He knew my canon of music. When you meet these guys you don’t expect that they know your shit. Same thing happened with Sammy Davis Jr.

You produced Cristina’s version of Leiber & Stoller’s ‘Is That All There Is,’ right?

AD: [big smile]Yes I did! [laughter] I was too embarrassed to tell him. We had asked his permission when we did that, because we fucked those lyrics up bad. Me and Michael [Zilkha] wrote to them saying we love your version, here’s ours. And they said ‘under no circumstances are you to release this’ but Michael released it anyway and it became a’ underground thing.

When I met Sammy Davis Jr, years ago, we were doing a show together in New York. I met Lena Horne the same time, and Cab Calloway, and shared a stage with Cab Calloway at Carnegie Hall. These are highlights of my life. For Sammy Davis to come over to me and introduce himself to me – that’s the power of music. That’s what keeps me going.

Sammy was/is unbelievably underrated as a singer, possibly not least by himself.

AD: So true. His records aren’t even available these days, the younger generation doesn’t know Sammy Davis Jr. Great vocals, man.

The sad thing about Sammy, and I have to be careful how I say this…

AD: You don’t have to be careful with me!

I should have guessed that shouldn’t I?

AD: Yeah!

…he’s maybe seen a bit as an Uncle Tom-ish figure. Someone who could make himself unthreatening by appearing clownish.

AD: Exactly. That’s how he was viewed back then by the so-called militants. That’s why he doesn’t have the reputation today. He was always smiling too much, playing the minstrel and his legacy was tarnished, but we shouldn’t let that diminish his great talent. Probably he was just trying to survive! We can’t judge what happened back then by today’s standards. It was an honour to meet him.

That’s the thing with music – you never know who’s listening. For Mike Stoller to say he knows Kid Creole..? Woah – wait a minute. Mike Stoller who wrote “Jailhouse Rock”? Stop it! Even at my age I still get impressed.

When I met Paul McCartney at the British music awards way back in ’83 or something, when I got an award for Best International Act, it was like ‘Paul, brother – you have no idea how good it is to meet you, because my brother and I used to listen to your music and say we want to be songwriters like Lennon and McCartney.’ – Self-contained, in their own group, not going to outside source for a song, not going to Holland/Dozier/Holland – writing great songs themselves. We were influenced also by Buddy Holly – who was American and wrote his own songs. But Lennon and McCartney were for the new generation – it was psychedelic, it was hip, it was bam! Boom! Great melodies, great hooks. So I met Paul, and next to him was Michael Jackson who was also up for an award. This was before he messed his face up. He was still… semi-human. Nice guy, down-to-earth, beautiful. People ask what turns me on… What turns me on is the universality of music.

Do you remember saying “The beauty of music is its possibilities for mutation, and that mutation represents a larger global ideal: global coexistence”?

AD: [genuinely surprised] Oh my god! [laughs] When did I say that?

To the New York Times, 1981.

AD: I still feel the exact same way. As I said, it’s because I’m not a purist, because I’m not good enough to be a purist. I don’t understand reggae like the reggae guys do. I like it: I like that the bass is hitting on the off-beat and the bass drum is hitting here. I can dissect it and tell you what it is, but I can’t do it like they do it – so I don’t want to. I want to borrow from it and take it to the next level, which is what ‘Annie, I’m Not Your Daddy’ did, borrow from Lord Kitchener and Mighty Sparrow.

Going back to Leiber & Stoller – particularly with ‘Is That All There Is,’ and I’m guessing you’re a fan of that strange album they wrote for Peggy Lee, Mirrors…

AD: Absolutely. Please! Absolutely.

…they can be completely twisted.

AD: Exactly! That’s what I like about them.

In the Savannah Band, the music is always really sweet, even when the lyrics are not. So you have to listen.

AD: Yes.

With Kid Creole, there’s always something weird going on – and it’s much more evident. There’s always an unease, a dislocation.

AD: We have a saying: my brother created this. We’d write a song, it was a pop song. A hook, a verse, a chorus, a bridge: standard. After we’d listened to it, we’d be sitting around in the studio, he’d have joint – he was never without a joint in his mouth – he’d say ‘Let’s fuck it up.’ Like the last song on I Wake Up Screaming, ‘Just Because I Love You’ – it’s so poppy, that you have to mess it up. There’s always something a little… off target. That’s how I get my kicks. Because at my age, you’d better get some kicks. I’ve been there, got the T-shirt, every accolade known to man, toured every country in the universe, but I still love song-writing.

So how come it’s been so long since the last record?

AD: Well, it was 1997 when I started doing Oh What A Night – this musical. I did 1,000 performances. Lost my mind! Basically, if you asked me at 15 what my dream was, it was to be an actor. I majored in drama [but] became an English teacher. Stony took me out of that by making fun of me – saying because I had a nine-to-five job I’m a pansy – he brought me into the world of the music business. I enjoyed it, toured the world, had a great life – never went back to acting.

Those Kid Creole records are like little plays.

AD: Exactly. Kid Creole was my ‘frustrated actor’ creation.

…and the Coconuts are the Greek Chorus.

AD: Yes! They’re the ones who cut me down to size; Coati Mundi was the comic foil. It was all very theatrical. It came right out of theatre training. If I couldn’t become an actor, I was gonna get my shit anyway. Then the hit records dried up and there was a lull. And along comes this phonecall: do you wanna do a musical? I thought, wow, I majored in drama 700-years ago, never pursued it, and then someone out of the blue offers me not just a part, but the lead role. I played a DJ called Brutus T Firefly. It wasn’t Shakespeare, I didn’t have to learn 8,000 lines. I sang a couple of songs and toured England and Europe. That took up nine years of my life! I was still recording, still writing for other artists, still putting out independent singles in Japan and South America. Just to keep your craft – you don’t wanna lose your craft. And then Quinton Scott [of Strut Records] phones up and says, ‘I got this great idea – I’m gonna put you together with Andy Butler.’ I hadn’t heard of Hercules and Love Affair. I’d done 1,000 performances of Oh What A Night and I didn’t want to do 1,001. I listened to Hercules, and thought, wow, this guy’s really influenced by Savannah Band and Kid Creole, this could be a good match, after nine-years of not doing a proper studio record [though] I have a studio in my home in Sweden.

How long have you lived in Sweden?

AD: Five years. Before that I was in Denmark for five years. Before that, none other than Manchester, England. Don’t spread that around! I got two children from the Manchester connection, who are in a band now – Picture Book, they helped produce this new album – my sons. And I have a daughter in Sheffield. So Manchester, Sheffield, Denmark, Sweden – and the next time you interview me I might be living in Venezuela!

Why did you leave the States?

AD: Oh! I cracked one day. I had to go to the doctor, and the doctor’s office was ten blocks away and it was raining. I took a taxi, and it took two hours. I thought, I don’t need the kind of life when the simple things become pitiful. I’d already grown tired of New York because there were no more surprises. We had milked New York of everything it had to offer: recording contracts, studios, fame, fortune – girlfriends! Everything possible. But the straw that broke the camel’s back was the taxi ride. It’s the little things that kill you. I already had a love affair with Europe and Scandinavia. And I loved me some London in those days, because oh boy was it happening. So I thought I’d head over here. I went up North, because I had a girlfriend from up north. When the relationship in Manchester fell apart, I went to Sheffield; when that fell apart – kept moving [laughs]. So I turned my back on New York, but it gave me the greatest inspiration in the universe. I’m still a New Yorker. Don’t forget I’m the guy who wrote ‘When you leave New York, you go nowhere’ in ‘Going Places’. The reason the new record sounds like New York is because it was mixed by Brennan Green who lives in Brooklyn – not just Brooklyn but Bed-Stuy, which is like the Bronx, a nitty-gritty neighbourhood guy. And Andy Butler. But the reality is I now live in Sweden, and I go back to New York all the time.

How do you find New York these days?

AD: I arrive in New York with my girlfriend and I say to her, ‘You know, I’m gonna move back to this city! There’s something about this city – the restaurants – the boom-boom-boom! The theatre!’ Three days later, I said ‘I gotta get out of here!’ The greatest thing about going back to New York now is that I can leave. Has it changed? Absolutely! It’s become an island for the wealthy. In the old days it was for everyone. Everyone bumped shoulders. It had an edge, there was danger. Now the mayors have cleaned up the city so much it’s lost its sting, its vitality. Real estate is absurd, hotels – absurd. They’re saying: if you got a lot of money, you can live in Manhattan. If you don’t, get the hell out. They’ve pushed people into Brooklyn. They can stuff it. That’s not the way it should be.

You used Kid Creole to say some sophisticated, ambivalent things about race…

AD: …Yes. I’m glad you used the word ambivalent, because nothing is direct.

…Do you think America has changed for the better at all since those first records?

AD: The optimist in me would like to think it has changed, but it hasn’t. Obviously it’s changed because Obama is president something that could never have happened before – however, they’re about to kill him! They’re about to lynch Obama because they say he’s too blame for every ill in America ever. What’s happening with me, in my subtle ways, in my musical multicultural presentation of a paradise – I’ve always said Kid Creole was my utopia, my vision of how the world should be, which was why I had a female bass player who was respected all over the world – Carol Colman.

I think bass-players should always be women

AD: I agree. Just the other day to bring it back to reality: Adriana [Kaegi], one of the original Coconuts, has a webpage, and someone had written on it ‘three white girls and a black guy is so wrong’. This is 2011. I look at comments like that and think [heavy sarcasm], Yeah, America’s come a long way [laughter]. It’s something that’s inherent in the country and there’s nothing you can do about it. I’m sorry for the people that still feel that way. I will always present the image of multiculturalism, the fact that we can all get along if we try. It might seem a naïve message, but I like the naivety of it. I love the utopian vision, the idealism of it because even if it’s only in my little empire, my little world, then it does exist.

Even now, generally speaking, the music industry prefers black musicians to work within accepted ‘black’ genres.

AD: So true.

White artists are allowed to ape black genres…

AD: …as proven by the greatness of Elvis Presley. But the other way round is sacrilegious. The so-called record companies, the ones that are left – because they did get their comeuppance, and it did make me smile because they’ve been ripping off artists since the beginning of time – the record companies have been ridiculous when it comes to ethnic artists doing what they were ‘supposed’ to be doing. I have faced it: I encountered it at the biggest label in the universe, Sony. I had a guy tell me ‘I want your records to sound like this’ – and I forget the name of the band, but he put on a record of an ethnic band doing so-called ethnic music and [pulls a face] right… The type [of music] he wanted me to be doing because I’m café au lait. It was the vilest thing he could have said because it meant to me that he’d never listened to Kid Creole, he didn’t know the history. It was one of the biggest mistakes of my career when I went with Sony instead of staying with Chris Blackwell’s Island Records. I left because [Sony] were offering me rrrridiculous money, and in going for the money I committed suicide. Even though Tommy Mottola was still head honcho then, he didn’t have time for August Darnell – he’d gone on to bigger things – he was married to Mariah Carey. When I called him for help, I couldn’t even reach him. So I just sat [in the the A&R guy’s] office and thought, Oh sweet Jesus. Because when someone tells me how the music should sound, I go the opposite way. He’s basically saying, if your skin is that colour you should be dancing, that to me is so offensive.

That’s – I hate to say it – racism. Kid Creole has always encountered that, but never in Europe. No one in Europe has ever said that because you’re café au lait you should be doing a certain kind of music. It’s an absurd notion. That’s probably why I’m still in Europe.

I ignored the advice, gave them a typical Kid Creole album as I would see it, and the album died and the band went through a very, very down period at that point and that was probably the last time we were with a major label who had the power to put us up in the stratosphere. I know that was a big mistake on that part. You learn from it: I tell my sons, never go for the money! You should make the music you’re comfortable with, no matter the colour of your skin.

Talking of European things, did you choose the Coconuts – who were white, of course, with very ‘white’ voices, deliberately?

AD: Well, my wife was from Switzerland, and she had a voice that was pure Caucasian, untrained – boom! So I said, I have a choice – I can bring in trained voices and make it sound like every other record, or I can use untrained voices and make it the sound of Kid Creole. From the very beginning that was a calling card for us. People would say ‘The Coconut voices – they’re so wrong, but they’re so right.’

They have a blankness that cuts through.

AD: Yes. I love the sound of untrained voices. That’s theatre training again – sometimes you have to cast things for a specific person. Sometimes it’s not about how great you can sing or act, but do you fit the part.

Of course at the same time it was becoming de rigeur for white bands to have black backing singers, being ‘in quotes’ soulful.

AD: Absolutely Ab-so-lute-ly! I went just the opposite way. That was intentional, in the same way that Kid Creole wasn’t what people expected a band like that to be at that time. That’s how crazy songs like ‘Mr Softee’ [about impotence] came about, crazy self-punishing songs. Ridiculous songs like ‘There But For The Grace of God’ [by Machine], with ridiculous lyrics that everyone got offended by. That goes all the way back to ‘Cherchez La Femme.’ The hook-line, where I got hate-mail was ‘They’re all the same, the sluts and the saints.’ Hate-mail came in: ‘how could you say such a thing?’ but the point is, Hey, at least I got your attention didn’t I? There’s always going to be double-entendres, there’s always going to be word-play – but most importantly there’s going to be things in the live show that jar you, upset you, that are going to make you say, ‘Why is that that way.’ America is the only place in the world where I’ve had people say, ‘Why aren’t there any sisters on stage singing?’ I say, ‘Wait a minute – this is the Coconuts, this is the image. Blond, blue eyes – sorry if that offends you. My wife chose two girls who look like her, that’s the image.’

Words like mulatto and mongrel still feel difficult.

AD: Mmmm. Oh god. That’s that politically correct thing. We’ve gone so far to the other side we’re afraid to call stewardesses stewardesses. Labels have become so powerful. Mulatto music is a funny thing. The word goes back to slavery. The term I really am against, and have told people to stop using in my presence is half-caste [laughter]. That is like the worst thing you could say. My daughter came home from school the other day and said ‘Someone said to me that I was half-caste.’ You know, if half-caste means of mixed heritage then the whole world is half-caste.

I said, You should turn to that person and say they need to educate themselves. Learn what it really is and where it originated because it is a derogatory term that needn’t survive in 2011. I take it lightly because the world is full of people who are going always to use the wrong terminology. Someone the other day referred to a ‘coloured’ person. ‘Coloured’ is a term that was used in America in the 1940s – so what. They haven’t moved passed that but so what? It changes every year. First it was coloured, then it was negro, then it was Black American, then it was Afro American. No wonder they’re so confused they don’t know what to call the tribe anymore.

Have you ever thought about writing a book?

AD: Yes. I have started a book. Five years ago. The bad thing about writing a book is I have a bad memory, and I shouldn’t have waited so long to write because a lot of people with better memories [who might have contributed] than mine have died. I’m also working on two musicals: I’m a Wonderful Thing Baby – with songs from the Kid Creole canon, and Ivy League which hopefully will debut in 2012, a semi-autobiographical murder mystery. It’s very, very, very noir-ish!

You love those classic Hollywood noirs, right?

AD: Oh man you have no idea. I was weened on those films. This album [cover] was in fact a complete rip-off the film I Wake Up Screaming, with Victor Mature and Betty Grable. I loved that movie. I thought it was such an appropriate message for today’s world. Climate change, Afghanistan, the drought, the tsunami – all happening at once. But also pin a personal way: the decade has been weird – great for me career and in my personal life, but in that one decade I lost my brother and my father and my mother. It was like waking up one day and saying, Oh shit, I’m an orphan again. I’m a bloody orphan. So I went back to the movie I loved as a child. There could be no other title for this album.

You actually look uncannily like Humphrey Bogart on the sleeve.

AD: [huge laugh] You’re the second person to say that! Oh SHIT! Ha!

You look like black Bogart.

AD: Shit! That’s fantastic! [more laughter] I hadn’t picked up on that. You know, Casablanca’s my favourite movie of all time. Bogart was my man. Bogart was the man who taught me how to walk. I imitated him so much as a kid. ‘I want to be like him, man he’s so cool. He’s got the Fedora, the box suit with stupid wide lapels.’ I used to look up at the screen and think, how could you be any better than Bogart. God damn was he cool, and then I fell in love with the females – Joan Crawford, Ingrid Bergman, Catherine Deneuve – oh, jesus. I was crazy about cinema, still am.

So, do you think there’ll be a big wait for the next album, too?

AD: No, it won’t be ten years. As I was writing this one, the Muse appeared again, so there’s a lot of music on the shelf in Sweden ready for the next album – and god forbid, if this one should sell, there’ll be even more motivation. I got the juice – it’s happening.

How do the characters of Kid Creole and August Darnell relate to each other these days?

AD: They have merged. There used to be differences. The creation was there so he could get away with ridiculous things. I actually used to use that line to my wife: ‘Oh that’s ok baby. Don’t blame, me – that’s Kid Creole doing that…’ I’m in a good place now. When you’re younger you think happiness, [even] if you’re in a relationship, is being single and [sleeping around] – as you grow older you realise that’s a joke you fed yourself because your ego was leading you into caverns of despair! It’s a question of maturity. I think the two characters have come together, to join in the harmonious mission of having a happy life… Actually, that could be a song title…

What, ‘Caverns of despair’? I was just gonna suggest that!

AD: That’s the next album! [laughter] Caverns of Despair!