All pictures courtesy of Kevin Cummins

Anyone flicking through Kevin Cummins’s newly-released book of photographs of Manchester musicians, Looking for the Light Through the Pouring Rain, could be forgiven for thinking it was impossible to go further north, psychogeographically speaking. That’s before Bradford’s Salts Mill gallery organiser and self-described "mill-owner’s daughter" Davina Silver got in touch.

"In the late 70s", she tells The Quietus, "my dad [the late Jonathan Silver] decided he wanted to go into men’s fashion, and he set about creating Jonathan Silver Clothes, these quite legendary clothes shops in the North, in Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds. The idea was to bring London fashions to the north at affordable prices, but all the designs were Jonathan Silver originals."

In the 80s, the Silvers sold up and went travelling, but on returning to the UK in 87, the Silver patriarch purchased Salts Mill, and regenerated it into the gallery it is today, amongst other things the permanent home of an extensive collection of David Hockney works.

"Years later," Silver continues, "my sister’s friend was reading Deborah Curtis’s Touching From a Distance, and read the line ‘Ian Curtis got married in a Jonathan Silver suit’. And the book has a picture of him wearing this pale pink pinstripe suit. We started thinking about this weird scenario whereby my dad was maybe some kind of icon to all these musicians that we look up to as our icons. And I then saw the Jon Savage-scripted documentary about Joy Division, and there was a shot of some expenses receipts from ‘Jonathan Silver Clothes’.

"And then we discovered this photo that Kevin had taken of Joy Division in another of my Dad’s shops called Art and Furniture, on Chapel Walks in Manchester. And I was stunned by the repeated crossing of paths."

"So I got in touch with Kevin, and he told me about the book and exhibition, and I immediately thought about how amazing it would be to put it in the space at the mill. We have a room that when it was built was actually the largest room in the world, which we don’t normally open to the public. And then Richard Goodall Gallery, who have been showing the pictures in Manchester, extremely kindly agreed to lend us the exhibition, so it’s all thanks to them that this has come together really."

Kevin Cummins discusses his work

===============================

What struck me first, looking through the book, was that it chronologically documents the changes of the city itself, as well as the bands. You’ve got the run-down Electric Circus era, and the bleak backdrops of the Joy Division and Buzzcocks photos. But gradually you see regeneration starting to happen, the appearance of the Hacienda, the disappearance of the old Hulme crescents . . . Were you conscious you were cataloguing that process?

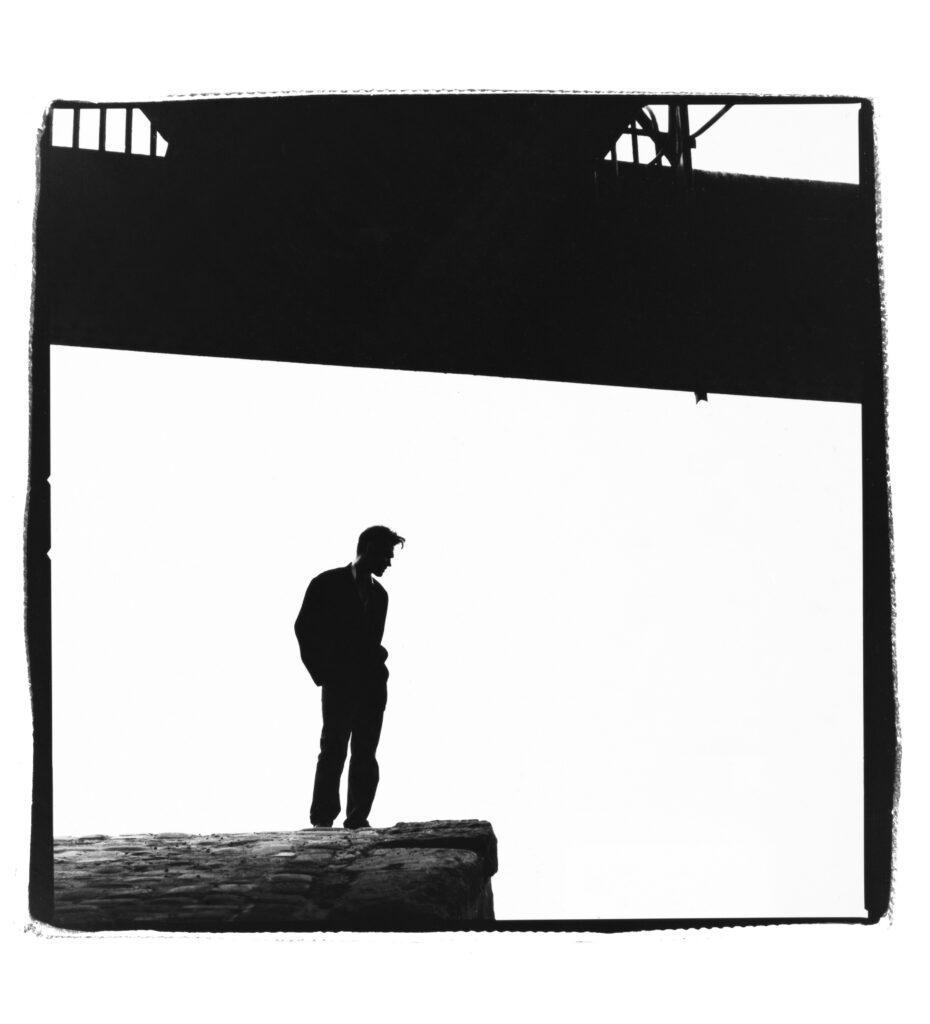

Kevin Cummins: Not initially, but when I was studying photography at college, there was a lot of regeneration in Salford, and I photographed a lot of that. So when I later started photographing bands, I was interested in putting them into landscapes, rather than doing obvious band shots. So consequently the Joy Division bridge shot, which is one of the more enduring images, to me it was actually a bleak snowy landscape of Hulme, and they just happened to be part of it. And with distance, obviously, it does locate people very much in the time and space.

If I’d have just taken Joy Division into a studio, it wouldn’t mean anything. What interested me was that you want to see the environment these people are working in and working from.

That’s why also I’ve put pictures in the book of dirty Manchester streets and so on. The book starts and finishes with royal murals on gable ends, and it comes full circle. When we were going to punk gigs every night, we thought that was the most important thing in the world, but outside of our circle of maybe 200 people, people were painting union flags on the sides of their houses. They had no idea the Sex Pistols were playing a few hundred yards away.

I suppose it only becomes apparent in hindsight, but the book has a real narrative, starting out with this little scene and ends up with these globe-bestriding phenomena like Oasis.

KC: Yeah, I agree. I didn’t want it to be a random collection of photographs, and it’s taken about four years to edit it. It took me a while to work out what the book was supposed to be. I got slightly lost when I was editing, because I had about 3,500 photographs and I had to stop myself from making an A to Z of Manchester Bands, which I definitely didn’t want. I wanted it to tell a story, a story of the city.

For me there’s a lovely flow to the book; when you get towards the end of it, you’ve got people obviously looking older, and it becomes more melancholic — Ian’s memorial stone, and the guy with Love Will Tear Us Apart tattooed on his arm — and it holds together well. I’m really really pleased at the way that works.

Your photography does have quite a consistent character, and a lot of your memorable shots aren’t, as you say, standard concert shots or band shots; they tend to be these more composed and placed things. Did you feel that you were documenting, or were you trying to steer or draw out something about how these bands would be perceived?

KC: Bit of both, really. I was probably more conscious than the bands that I was part of their myth-making process. So, for example, I’d never release pictures of Ian Curtis smiling. Because that’s not how I wanted them to look, and it’s not how they wanted to look, and it’s not how we wanted people in the rock press to perceive them. So like the shot of Ian sat against the black wall; I put the overcoat on the hook, as a visual pun. Because the music press used to call it all "grey overcoat music". So we put that in for our own amusement.

John Squire wouldn’t have painted himself in sky blue and white if he’d thought about it. I was always trying to get Man City references into images.

And then with New Order, we went to the states in ’83, and I thought, "let’s do something completely different". And I shot them separately, tight head shots, but lying against a blue swimming pool. And suddenly it was alive, different and vibrant. And that helps to change the way they see themselves as well.

About five years ago, I did a talk at the Cornerhouse with Tony Wilson and Bill Drummond, about media manipulation. And I told them the story about how I never released pictures of Ian smiling, and how that was what I brought to the table. And at the end of the talk, I was approached by this girl who said "So . . . do you have any pictures of my dad smiling?" And that was Natalie Curtis, who I’d not seen since she was a baby; I think she was on some kind of voyage of discovery trying to find out about her father’s friends and so on.

Did you have private photographs to give her?

KC: I’ve got odd shots of him smiling, but because at the time I was paying for my own film, I couldn’t afford to do too many candid pictures. I’ve told this story lots of times, but if I was doing a band shot for the NME, you’d get £6.50 a shot, but it would cost me a tenner for a roll of film and the processing. So I was losing £3.50 on every job. Which is why in the end I started doing things like the New Order head shots, because I thought, they’ll have to use four shots if I do it like that, so I’ll be able to pay for the film.

There are some shots of Ian smiling, but if he did, I’d say "stop smiling, stop messing around, I’ve only got five frames left". And I suppose this is all why the photos are so iconic, because there are so few of them. Nowadays, you just photograph endlessly. But then, there was a proper punctuation to the session. You’d get to 36 shots and you’d have to stop and re-load. And then you move into a different moment.

Without them realising sometimes, you’re working a lot off each other. For instance, the Buzzcocks picture, in the library, when they saw that, standing in the Fiction and Romance section, Pete Shelley wrote a song ‘Fiction Romance’, because of that photograph. So it is a collaborative effort, though the bands themselves often won’t want to give credit for that. But I’m not here to make them look stupid. When you look at the book, it’s really a love letter to Manchester and its music.

I guess all this stuff did spring out of a collaborative culture.

KC: I think so, yes. Morrissey is perhaps the exception, but most bands — the ones I worked with — didn’t have a strong idea of how they wanted to look and were open to suggestion. So there was no real point in trying to photograph Happy Mondays like Joy Division, because they’re something different. And similarly the Stone Roses paint shot. I suggested that to them a few months before we did it, and let them think about it. At the time we were doing stuff with them in Paris and Amsterdam, and we got some shots, but in the back of my mind I wanted to get them home and do the paint shot, as I felt it was the right time for the image. And again, they weren’t really into the idea just then. You almost have to make bands feel like it’s their idea sometimes.

But, you know, John Squire wouldn’t have painted himself in sky blue and white if he’d thought about it. I was always trying to get Man City references into images. When I shot New Order for World In Motion, we were putting Bernard Sumner and John Barnes on the cover of the NME, and I had to get Umbro to send me a limited edition blue England shirt, as I wasn’t going to put a red shirt on the cover. Petty little victories I won occasionally.

Tying that back to the thing about the overcoat, there’s a lot of humour in a lot of these images, relating to bands’ perceived identities. I love that picture you’ve got of Andy Rourke with his head in his hands. It’s almost a parody of a Smiths photograph.

KC: I know! But we’d reached a point where we couldn’t think what else to do.

The Buzzcocks picture, standing in the Fiction and Romance section of the library — Pete Shelley wrote the song ‘Fiction Romance’ because of that photograph.

I don’t really force people to do things for photographs. I stand with them and wait for something to happen. It’s very similar to the idea that when you put people who aren’t used to being photographed into a photographic studio, they’re out of their natural environment, and they think, "Right, I’m supposed to do something here aren’t I?" So you’re making them work for you a little a bit.

I think the strength of a good portrait is getting the person to almost forget that the camera is there, so they’re relating to you a little bit. I think a lot of photographers think it’s about them. But I want that picture to say something about Andy Rourke, I don’t want it to say too much about me. Though it’s got my style and the way I frame things; that side, the technical side is me. But it’s a picture of Andy Rourke.

The photographers I was really interested in when I was studying photography were Bill Brandt and Diane Arbus, and both of them developed relationships with their sitters. And I think that’s what I’ve done. A month ago I was photographing Bernard Sumner again, 32 years after I first took his picture. And that’s a great testimony to the relationship I have with people. I don’t stalk them or live in their pockets, but they’re good enduring working relationships.

So do you find it more interesting to work with bands who you know, or know something about and where they’re coming from?

KC: Yes. I’m not very happy photographing people whose work I don’t respect. Sometimes you have to, editorially, but I’m in a fortunate position in that I don’t get sent out every day to do stuff I’m not interested in, and I get to pick and choose a bit. Not that I only photograph people from Manchester, though it bloody feels like it right now!

So the book is chronological and there are more recent images, but a lot of the later stuff is still guys like Ian Brown and Oasis. There isn’t much there of more recent bands.

KC: I don’t know really. It’s difficult for me. Because I haven’t shot Elbow — but they’re not from Manchester, they’re from Bury — and The Ting Tings in a way aren’t part of a Manchester scene. The stuff in the book is really bands who were of a scene that developed around them in their own city. Probably Doves are the last band like that. I might be wrong, but that’s how I see it, and like I say, it’s not an A to Z of Manchester bands.

It has to be my story too, I think. When Faber initially approached me they asked if I wanted to do an autobiography, and in a way, this is my autobiography. Really, it was like reading old diaries, and that was quite difficult. Because it opened stuff up, things long forgotten.

I really like the blank "afterword" page at the end attributed to Tony Wilson. Obviously, he’s a huge presence in the book, and through that whole era. Do you think the absence of an ambassador like that changes things?

KC: Yes. The thing with Wilson was, on one hand he came across as terribly arrogant, but he was also very self-deprecating. He had enormous confidence in some areas and not in others.

But he did an awful lot, and when he died, suddenly people realised that this conduit everything had gone through wasn’t there any more, and people were floundering for a few months I think. Because although he’d allowed people to parody him, he actually did a lot of work.

A lot of people, Factory people especially, used to say to Tony, "It’s all right for you, you’ve got a job. I’m trying to be in a band, and you’re giving me ten quid a week". But money wasn’t the motivation. It would be unfair to say "if Tony had been hungrier things would have been different". The fact is, no other city in Britain has got such a wealth of musical history now, and he facilitated a lot of that. I mean, look at Merseyside. That wave of post punk bands that came along didn’t really have much longevity. Frankie Goes to Hollywood were great for a while, and Echo and the Bunnymen — great bands at the time, but [they] sound curiously dated now.

I suppose that was the thing about Factory, who else would have had the vision to sign a lot of those bands?

KC: Yes. I feel Tony’s greatest strength was putting the right people together. He would say "I want you to meet this person", or he’d put a band in touch with a producer. It was like some weird experiment, where he’d put opposites together in a room to see what happened.

Were you a beneficiary of that?

KC: Oh, definitely. Not financially! But yeah, when he introduced me to the Mondays, he just said "I think you’ll get on". Same with Vini Reilly and lots of others.

Of course, a lot of the biggest Manchester bands consciously avoided the Factory circle. I remember having a conversation with Mick Hucknall donkey’s years ago where he was saying "No disrespect, but we didn’t want you to take our first photographs, because we thought that would categorise us as a Manchester band, and we wanted to be something different". Even when I eventually did the photo of Mick that’s in the book, for an early NME piece on Simply Red, we had a long conversation about it, where he said "Why don’t they send somebody else up other than you?" (laughs)

Perhaps this is nostalgic, but there’s a body of stuff appearing — your book, or the spate of Joy Division/Factory films and so on — that feels it’s bookending an era, a certain way that music was made and consumed that’s now over.

KC: Yeah, I think so. It isn’t meant to be a tombstone, it’s meant to be more celebratory than that. But yeah, digital has changed everything; the way we buy music and perceive it. And this is still a period that people are very unsure about. It would be very difficult, I think for someone to come along and do the next 30 years. It wouldn’t be done in this way, certainly.

And it is nostalgic, but that’s all right. It’s not false nostalgia, a period not lived through. I think when people are looking at it, they’ll dig out some old CDs and what have you.

Yeah, I stood in Waterstones looking through it, and immediately put on A Certain Ratio on my iPod

KC: Ha, great. I’ve had a lot of emails from people saying they’ve bought the book and how it makes them feel proud to be from Manchester, which is really gratifying.

Yes. I think my favourite photograph in it is the one of The Fall outside the Friends’ Meeting House in town. Because I love the fact we’ve got the Friends’ Meeting House, and everything that goes on with them, and I also love the fact that we’ve got The Fall. It couldn’t be anywhere else.

KC: The Fall, because Mark’s still going strong, they’re consistent in every period. And I was determined to reflect that, with shots through all the eras. Where else would you have a band like the Fall, lasting 32 years and making 80-odd albums? And being allowed to make them.

I really like the shot of the cables all twisted round the mic stand. Because that is The Fall. If you’ve ever seen The Fall live, that’s the shot.

When I did the talk with Bill Drummond and Wilson, I was talking about the power of photography, which I believe is more powerful than the written word, no disrespect meant to writers. And they were disagreeing. But I raised some of the covers I’d done, the Stone Roses paint thing, and Shaun Ryder on the big E, and asked them who wrote the features that went with them. And they didn’t have a clue. And people don’t remember; people remember the picture.

Well, pictures have a greater reach, don’t they?

KC: Yes, they have a resale value where the words usually don’t. Which is always the beef writers have with photographers. (laughs)

KEVIN CUMMINS – MANCHESTER: LOOKING FOR THE LIGHT THROUGH THE POURING RAIN runs from 30 September to 16 October. On Sunday 11 October at 3pm Kevin Cummins will be in conversation with Kevin Sampson about photography, music and Manchester. Tickets £5 (£3 concessions) are on sale in the 1853 Gallery or by calling 01274 587377 (10.30am – 5pm). Salt’sMill.org.uk

Click on the picture of Morrissey below to enter our gallery of Kevin Cummins photographs, including a shot-by-shot guide from the man himself. . . .