It was back in 2013 that Kelela Mizanekristos’ mixtape Cut 4 Me dropped, unleashing a mystical fervour in its wake: this was a mesmerising new R&B sound, all powerful, soulful vocals melded with glitchy, ominous dance beats. Sonically, it was radical – her work with a variety of mammoth underground producers (Jam City and Girl Unit, to name a few) seemed a marker for just how ambitious the genre might yet become. The tape was followed by a deluxe version, and then the gorgeous Hallucinogen EP – an offering that seemed to nod knowingly to the breathy, falsetto futurism of Janet Jackson, while embracing contemporary dance music (Teklife founder DJ Spinn served up several remixes).

And yet, in spite of all the very worthy hype that swirled around the Maryland-via-Washington D.C. artist, talk of an album has seemed constantly on the horizon but never realised. Last year saw a beautiful feature on one of the best albums of 2016 – Solange’s A Seat At The Table – but still there was no Kelela full-length. Thankfully, 2017 sees an end to the wait: Take Me Apart has now been released into the world, and finds Kelela building upon the foundations that Hallucinogen laid out. It’s an album that’s as vulnerable as it is sensual, pulsing with a tender production that’s perhaps poppier and more accessible than we’ve heard before, but no less striking.

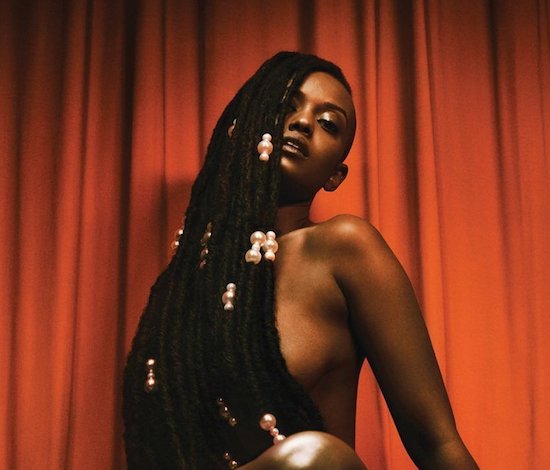

The cover art shows the second-gen Ethiopian-American sitting cross-legged, staring almost challengingly at the beholder: poised, unapologetic, and naked, save for masses of long braids artfully wrapped around her. Such a cover is symbolic of many things, but the braids seem a reminder that – though the album never gets explicitly political or talks expressly about blackness – Kelela is a queer black woman who grew up in the States, and her art is inherently formed through the lens of that experience.

Largely, this is a record that deals frankly with relationships and sex – ‘S.O.S.’, for example, finds her texting a lover asking them to come around (“I could touch myself babe, but it’s not the same if you could stop and help me out”). There’s a visceral rawness to the whole thing, but none of it feels overbearing – instead, it’s delicate, deliberate, and highly curated. It’s telling that some of the songs on Take Me Apart have actually existed for years, but are only coming out now – with striking prescience, as early as 2013 Kelela knew that she wanted tracks like ‘Enough’ and ‘Jupiter’ for an album, not the tape or the EP (“I knew when some things were born they just weren’t ready to be shared, because it didn’t fit the trajectory – this is not first season, this is deep in!”).

Indeed, when I meet Kelela in early August to talk about the album, she’s perched in her Shoreditch hotel room and everything she says feels measured and considered. It’s as clear from the way she talks as it is from her intensely intimate soundscapes – Kelela is an artist very much in control of her vision.

I feel like we’ve been talking about the album coming for a couple years – is there a specific reason that it’s only coming out now?

Kelela: It just took a long time for me to complete, for so many reasons. It’s partly the way that my personal life and experience is happening at the same time – I’m drawing upon real life shit that is happening at the same time, so those experiences can be very overwhelming. Experiencing the music industry for the first time – all of the “first” stuff regarding my career happening during the period where I was making this album. Relationships, friendships, management – there were so many things that aren’t hard to fathom. But primarily it’s because I did a lot of experimenting with different sounds for each composition and, yeah, it took me a while to decide on what was best for each song – I’m trying like four different versions of the same song, because I find value in so many different sounds.

You work with a lot of different producers – Arca, and Jam City, for example. How does that relationship work when you’re making a track?

K: There are different ways that it’s worked. It was all part of my experiment: so it was like, find out – what are all the different ways you can arrive at the thing? There are very few tracks that just exist and I sing over – I think there’s probably one like that. One of the ways was to sit with the producer and compose from scratch together. With Jam City when we did that, it was just so light and fun and fluid – I know that he just gets what I’m trying to say, and the things he intuitively does is just so everything. Then the next level I would say is tracks I heavily altered – I wouldn’t be there during the inception of the instrumental, but then I would do so much to make it my own. So that would mean asking this producer over here to do drums, asking another person to do the synth – asking, “What is the synth I’m looking for?”, trying to find the sound that fits. And so working with several people on the same track can be really long – especially when those people don’t live in the same city, so this is kind of my reality – I’m fully happy to deal with it, but it’s something that requires time.

With your earlier work there was almost a grime sound – all that very abrasive production. And while there are elements of that still, overall the album feels like you’ve pulled that back a bit – like it’s powerful in a different way? Do you feel like the songs are a statement of where you are right now, sonically?

K: The mixtape was definitely more heavily leaning towards grime – but I guess I never had a really specific idea of what the album was supposed to sound like? I just knew that it had to sound new – and there had to be a range. The things that I was committed to was criteria that was unrelated to specific sounds – my goal was to be expansive, while reconciling disparate things. That is part of my sonic identity, and I feel like I’ve established that through the album in a way that I’ve never been able to with previous releases.

On the album, you approach sex and desire in a very raw and vulnerable way – but also the lyrics seem to reference something more casual. I’m not sure if you saw that Björk has said her newest album will be her “Tinder album”? Do you think, similarly, what you’re creating is a reflection of relationships in 2017 – that visceral, casual thing?

K: I would say that yes, it’s about relationships in 2017, but also just relationships in general. Relationships – how they’ve always been. The goal for me is to articulate the layered-ness and the complexity in those interactions – and I always try and pair multiple sentiments within the same song. So while I’m saying like, ‘Oh, I love you so much’, I’m also saying like, ‘Something is really not ok here’, but also ‘Everything is gonna be alright.’ I’ve always wanted to articulate that you can feel all those types of things at once – because I think that’s how things really are. I come from a school of being most moved by tender music, and vulnerability is a cornerstone in every artist I’ve ever been truly obsessed with. Those are the things that get me excited, and it’s the thing I want to articulate the most.

So how does that translate to Take Me Apart?

K: It might actually be the antithesis of love in 2017, if that makes any sense. ‘LMK’ is coming from a place where you are single, and you want to have something casual, but it’s demanding respect in that. And then it kind of becomes not so casual – I’m looking for quality, and maybe “casual” just implies carelessness? And I don’t like that part. If that’s what that means, then I’m definitely not into that – but if “casual” means we’re not having expectations of each other, beyond having absolutely amazing sex? Then I’m so fully here for that. Respectfully, though, but I think that’s the part that’s missing in the way we engage with each other right now. So it’s not inherently a Tinder thing, or an app thing – it’s how we’re training ourselves and other people to be in love, and how we have sex. So in a sense, it’s the antithesis – the album goes against that culture, because tenderness and vulnerability are usually not part of what it means to be casual. But I’ve never wanted to take that jacket off, even with lovers who I’m not in deep relationships with.

Right, because it still needs to be communicative – otherwise it’s just kind of empty.

K: Exactly, it doesn’t feel good! I can’t even enjoy myself lately if I don’t feel that respect, and also if you don’t know that I have feelings. I might not have those feelings for you, but I do have feelings, and I am a human being, and I do deserve to be treated with respect – and so do you. So I want to break it all apart, and make it more complex. The dichotomy of being in love in 2017, romance in 2017 – I want to make it more complex than just the reduction of, “Is it a Tinder thing or something real?”

There’s definitely still this area in-between a relationship and random hook-ups that’s not really addressed.

K: It’s something we’re not talking about, but I really want to articulate it – this place between where you don’t want it all the way, but you still want them to answer the questions that are being asked straight-up.

So is that what Take Me Apart means?

K: Take Me Apart is emotional, and it’s also quite sexual. In the emotional sense, I guess, no one would intuitively ask somebody else to take them apart – nobody wants to be analysed, or made to feel very vulnerable. And I love that so much, in the purely emotive part of romance. I’ve always wanted someone to make me put my guard down, and disarm me – to make me feel less frustrated, just to inspire me to let go. And then in a purely sexual context, it’s basically topping from the bottom – it’s demanding that someone pin you down. “Make me vulnerable, put me in a position right now”. The irony of how you’re actually the top when you’re demanding someone take you apart – it’s about the permission, that blurry line in sex that’s not so literal in real life.

I guess there are things you can ask for in that context, but there can still be boundaries.

K: Yeah, you can go pretty far, but still feel so respected.

I’m always hesitant questions like this because I know being put into these kinds of boxes can be frustrating – but, obviously, women in the industry are sexualised, women of colour even more so. So as a woman of colour, do you feel like being so open in your music is a way of taking ownership of that?

K: Instead of you defining it, it’s me defining it, yeah. As a queer black woman, it means the world to me, because I’ve experienced what it feels like to be a queer black girl growing up in the US. So all I’m thinking about when I write is – is it gonna be a safe thing for them to sing? Can they get in their car on a shitty day and sing this song and feel really good about it? That is basically what I’m trying to make sure of – that even when it’s sad, it’s really empowering somehow.

I read that the school you went to was predominantly white – so for you growing-up, did you feel like you had that kind of representation, and if not is that why you feel it’s important to be doing this?

K: Yeah, my school was predominantly white – though there were a lot of people of colour. But I guess because of where it was, the people of colour were bussed to school from like a ghetto suburb. We had to walk so far to the one bus stop for our neighbourhood – meanwhile the white kids in their neighbourhood who lived close to the school would be getting picked up in front of their houses. So you have a culture that values whiteness in a completely different way, and even among black people there’s so much internalised racism – amongst all people of colour. Needing to adhere to a stereotype of what it means to be black, or be called “an oreo” – these were our choices in that school, and I struggled through that because I didn’t feel like either. The way that I grew up definitely informed all of how I’m thinking about who I’m writing for now, and who I want to live from the lyric or the sound.

It’s not new, but I want to add to that for black girls: add to the feeling that you are fucking epic, that you are important, and that the wind is fucking blowing through your hair and you are the top of the mountain. These really robust, infinite feelings – when I think about the soundscapes that I’m creating, this is quite literally what I’m thinking about, which is something I’ve never articulated before. I’m thinking about a young black girl: can she feel that? More specifically, young black girls who don’t feel like adhering to one version of what it means to be a black woman. I’m wanting to articulate the infinite nature of that identity, and how much it can encompass.

So that’s what you were thinking throughout the album-making process?

K: I mean, the sounds I was describing to producers and the engineers I worked with are based on that feeling, which comes from a pretty visual place. It makes me think of Janet – I feel like she did give us a lot of….I can’t explain it. It’s more than sexiness – there’s a way that, through her visual language, she made us feel really important. Like, she’s so important, a black girl is so important. Especially when it came to the drama she put in, the chit-chatting and even like, putting laughter on a track! All the personality and the acting that would happen at the start of the videos, illuminating something about us that didn’t feel so much in the forefront. She made it epic – she was relatable, but also like, “You don’t fucking know me.”

In a similar way to that, with your music and how open it seems do you feel like fans have a false perception of how much they know you?

K: Again, that’s a layered thing. On the one hand I am not writing about anything but my own personal experience, and I’m trying to be as honest as possible about that – but there’s also a show. I’m trying to embellish, to make you able to connect with it even more. I work on my show so that I can really make you feel the feelings, reliably. But a certain amount of separation needs to exist between how I put myself out there as an artist versus who I actually am. I think it’s more about drawing lines – it’s less that I’m such a different person from what I put out, but I’ve learned in the time that I’ve been a visible artist that the only frustrations that come are when you don’t draw boundaries, or when you don’t have a mechanism in place to protect you from people wanting a piece.

I was thinking about other artists who have been doing similar things to you, albeit in a very different way – Solange’s album comes to mind, and I know you were involved in that. Can you tell me about how that happened?

K: Well to be honest, she wrote that whole song. And she sent it to me and was like, “Can you sing this part?” That’s literally how that happened. I connect with her so hard on the sentiments she’s expressing in the song, and I think that she knew that. There’s so many layers to it, but mainly I was just so floored by the lyrics. The chord progressions really blew my mind too – I’ve never seen anyone write that linear of a chord progression so effortlessly, like butter, I just can’t explain it. My goal with music has always been, you don’t have to be on some jazz shit, but I’m gonna make you like that – I’m going to make you be able to make sense of it, I’ll show you how. And the way she does that on that song, melodically, is a mind-blower, and then the extra layer of the lyrics is just so powerful. And so when she asked me to sing the final lyric, it is so me. It’s so poppin’, it means so much – it makes me wanna cry. I feel immensely grateful, but I did nothing but sing the part exactly how she sang it. It was blissful, and it is one of the best things I’ve ever been part of. Some of the songs on that album just made me weep.

It is an amazing album – and to go back to what that album deals with in terms of confronting race in America, that’s obviously a very nuanced thing. I know we were speaking about your experience as a kid, and this whole “oreo” thing, and you’ve previously spoken about the weird ground between wanting to push diversity without being tokenistic and thus being part of the problem. Do you think there’s a way of pushing this stuff forward?

K: There definitely is. In the past few years it became a capitalist thing – companies will lose money if they come off as not on the diversity train. And I’d say that’s a new thing, this link between profit and multiculturalism as a concept.

It’s even in the way that big corporations buy into Pride now.

K: That’s exactly what I’m saying. There’s buying into Pride, and alongside that there’s all of me and my black peers who are being approached on the daily about some “opportunity”. But really we’re talking about opportunities for the companies to not look so shit. So my new policy is, if you’re asking me to be the token – either, you’ve never had a person of colour or a black woman as the spokesperson or whatever the fuck it is – for the thing, and you want me to be the first? That costs a lot more than if you ask me to do something with me and a bunch of other people of colour. I never hate on anybody for taking those opportunities, because I’ve taken them – everybody has to survive. But right now I’m thinking about how to do it in a smart way, and how to be thinking about the messaging, and what it is that’s going on underneath that.

I guess we’re largely talking about the fashion industry with this stuff, and I’ve been wanting to ask about your aesthetic. You have a very distinctive sense of style, which I think fits with the sounds you create – is that something you consciously think about?

K: Yeah, I do think about it a lot. It was really hard for me to nail down what the visual representation of the album should be.

The album cover is incredible actually.

K: That means so much to me, thank you – I worked on it with my friend Mischa Notcutt, who’s my creative director and stylist. To me, the album feels simultaneously otherworldly and round the way, so it was hard to represent the vibe. I decided I wanted to be naked on the cover because it eliminated one thing – one piece of information. The only possible representation could be me naked, because it’s actually just all the things – kind of like using your actual name as your artist name. It solves the problem because there’s nothing else that could encompass all the things that I am, other than my name – it’s like an abstraction.

But at the same time, it does add to that vulnerability-meets-power thing we were talking about.

K: Exactly. It’s like putting yourself out there, and that was the major reason why. The only thread that existed throughout this whole album is not a sonic one – it’s a vulnerability. It would be scary for me to show my body in that way, so I knew I had to go there because it just matches with the sentiment of the record. And that’s such a risk for me. I feel comfortable in my body, but there are parts of my body that I’m not comfortable with – but that I’ve gotten more comfortable with just by doing the cover. It’s just a really interesting process. The album made me go hard at life – my life as an artist makes me go harder as a person.

Take Me Apart is out now on WARP