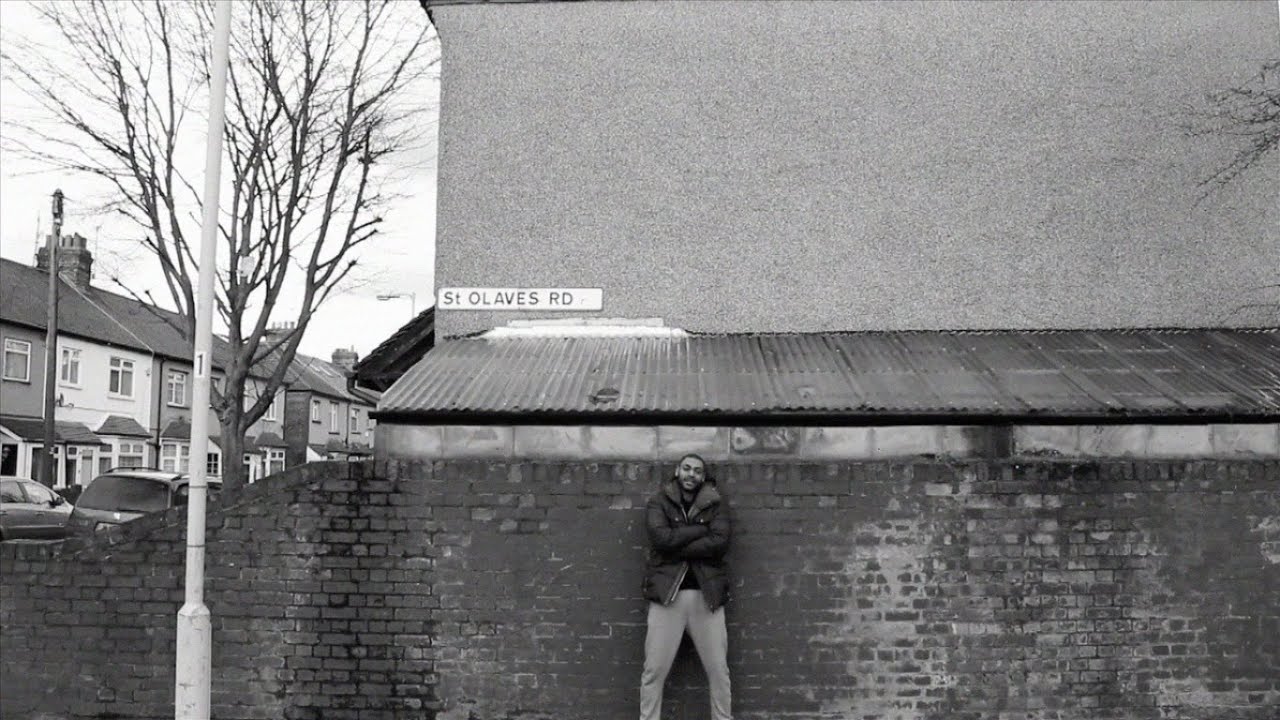

The opening scene to the video that accompanied Kano’s excellent comeback single ‘Hail’ late last year featured a close up of the 30-year-old rapper’s face. During the clip he scowls darkly from under a pulled up hood as he peers into the lens of the video camera he’s switching on. As doom-laden bells ring out, distorted guitars riff heavily away and synths whirr like rocket ships taking off, it’s clear that something heavy is going down. But as he retreats across the road to lean against a wall he suddenly breaks into a wide grin. Kano is here to have some fun. What transpires over the next few minutes looks like an absolute riot – hanging out with mates, drinking courvoisier, playing rock paper scissors, eating chips and listening to mixtapes… But eagle eyed viewers will notice that right at the start of the promo film, just above Kano’s shoulder is a street sign bearing a very significant address: St Olaves Road, East Ham.

Behind what clearly looks like a brilliant afternoon out in East London, Kane Robinson is making a very serious point. While he’s definitely pushing his music forward, he’s gone back to ground zero for his lyrical inspiration: the place where he came of age. This is where he lived when he was making his first tentative steps in grime and many of the tracks on his fifth album Made In The Manor concern his friends, his family and his rivals from this period. The follow up to 2010’s Method To The Maadness is inspired by the community that made him what he is today.

Made In The Manor, out early next month on Parlophone, has been toiled over, from start to finish, for well over two years and the effort and inspiration ring out clearly like a struck bell. It is as much a love letter to his East End roots as it is a forensic portrayal of inner city England today, with just the merest hint of dark prophecy about what trouble may lie round the corner… This is in some ways his most intimate record dealing with long standing rifts between him, friends and family members. At the same time it is his most sonically adventurous, combining many different styles with a newfound love for live instrumentation.

I went to met the rapper on two occasions for this feature. Once ten months ago as the album was just taking shape I was a guest round his house. (While he still lives in in East London and not too far from Stratford in the bigger scheme of things, he does live in what you could call a slightly leafier neighbourhood now.) As we drank coffee and talked I couldn’t help but notice the many photographs around the place. Plenty of shots of family and friends, not to mention a couple from his early years of MCing (one on his first tour with The Streets) and a framed black and white shot of Hendrix shredding at Woodstock. And then again last month at his studio in Hackney as he was just putting the finishing touches to the release surrounded by a huge old school mixing desk and piles of synths and other analog gear.

It’s been six years since your last album Method To The Maadness; why was it time for a new record now?

Kano: It just felt right. I’m always recording but it just felt like it was getting there this time. I wasn’t thinking: “It has to be now. I haven’t dropped an album since 2010… I need to put one out.” I felt it was important for this – my fifth album – to be saying something new about me, otherwise I’m just telling [listeners] what they already know which is a bit pointless. So until I had shit to say and felt comfortable with tackling certain topics [it wasn’t time to start]. But I feel comfortable now. I feel like it is the right time.

Are you in a different headspace when you’re writing for an album than you are when you’re doing stand alone singles or collaborations or putting out mixtapes?

Kano: Yeah… definitely. When I’m doing features I’m just providing my services I guess. I’m just doing what the tune requires and what the other artist has asked of me. It’s already laid out and I just fill in the gap you know. When I’m doing mixtapes it’s just more of a fun thing. It’s a complete hobby. It’s like it was when I first started out. There’s no pressure. You don’t have to worry about anything. You can do whatever you want. Doing an album takes a lot of thought. I don’t really think about it before I start but I review stuff a little bit more. I could just do a tune and throw it out but when I’m doing an album I’ll live with that tune for weeks, months or a year even. Just to see if I still like it. Also so I can tweak it. There’s a lot of tweaking going on.

Once you realise, “Oh, I’m making an album”, do you start corralling the tracks together in a certain way; thinking that they need a certain spirit or style to link them together?

Kano: Normally there’ll be a spirit. It’s mainly a lyrical thing but it’s also a musical thing as well. I’ll look for tracks that sound well together but they have to come from a similar lyrical place as well. What usually happens is you make songs and you make songs and you make songs and THEN you make one song and think, “Yes… that’s staying. We can forget about the rest of them… this is the theme we’re going to pursue.” Last year I made a track called ‘T-Shirt Weather In The Manor’. That track was what sparked off this particular body of work and set the spirit for what the album was going to be like.

There’s a verse on ‘T-Shirt Weather In The Manor’ where I’m talking about my journey from 2005 from when I first signed my deal to now. And that really gave me the direction lyrically for this album. The first line of it is, “69 Manor Road, Sunday morning…” And that was the house in Stratford that we grew up in before moving to East Ham. The house eventually got too full and we moved when to East Ham when I was two but I would go there every weekend. And I would spend the whole summer there. And this was until I left secondary school. And for me that brings back so many memories of good times with my family. I can still smell the food in the oven, I can smell the curry cooking in the pot, I can smell the barbecue ribs. It represents my childhood and my youth.

It wasn’t just us, it was an extended family and this was the real party home as well. I remember when I was a little kid, popping down at 2am because there was music playing and I’d try and sneak a little half an hour before I got told to go back to bed. Good memories.

That’s what a lot of this album is about – family and friends, these relationships and how they evolve over the years. There was a friend of mine called Demon who lived round the corner from Manor Road on Corporation Street. We used to go to playscheme together, then we went to football together, then he started MCing so I did as well; he got me into it. And then we went on our first tour together supporting The Streets. We fell out after that. That particular place makes me think of all of the places we used to go – hanging out and playing football. So the track ‘T-Shirt Weather In The Manor’ inspired another track called ‘Stranger’ which explains the story of our friendship and how we don’t speak any more. And that kind of spiralled out into a lot of other subjects which are covered on this album.

The whole album is full of real names and real street names – and not just famous people as well but the names of your mates and family members. Are you trying to root Made In The Manor in a particular time and place?

Kano: Yeah, definitely in East London. I was made in the manor and that’s where these stories come from. I grew up in and around Canning Town, East Ham, Plaistow, Stratford… Newham in general. So that’s why it’s heavily descriptive of East London. There’s a moment on the record during the track This Is England where I take it from describing East London to describing England in general.

There is certainly a melancholy edge to the track ‘Little Sis’ – would it be fair to say that this is more of a reflective album than any of your previous ones?

Kano: I’d definitely say that it’s going to be my most autobiographical album to date, I’ll say that. Yeah, there probably is a melancholy vibe to some of the tracks. That track is about the fact that I have a half-sister who I’ve only ever met once when she was very young.

I went to Lovebox festival once and someone came up to me and said I’m so and so’s friend. And I was like, “What the hell are you talking about?” And they were like, “You know, your sister.” And I was like, “I ain’t got no sister, I’ve only got one brother.” And after I said it I was like, “Oh fuck…” It really made me think. I wondered if she’d been telling her mates that she was my sister and I’d just been going through life thinking of myself as only having a brother. It just stuck in my mind.

Do you hope she hears it?

Kano: That’s the thing, I don’t even know if I’m ready for what that song’s going to bring but it’s just something I did. I like the song but I don’t know what’s going to happen after it comes out.

The lyrical idea that you might only meet at your dad’s funeral is pretty dark isn’t it? [Kano is estranged from his father.]

Kano: [LAUGHS] Yeah, er… every time I listen back to that I think, “That’s fucked up…”

Do you find it hard to write about this stuff?

Kano: I find it super easy to write about stuff that I would never talk about. I’m not really the sort of person who talks about personal stuff. But I can write about it, so I have to ask myself, “Is this too personal? Is it too much?” But the part of me that is an artist knows that this is what art is about and this is what albums should be about. And that part of me will always win and that’s why this shit will always come out. But the hardest thing is the nearer I get to release the more nervous I get about certain people who are close to me hearing it. I’m excited but nervous. I don’t know what the reaction from my family will be. Am I even ready for what these songs could bring? We shall see.

I’m interested in this period you spent partially away from making music. It feels like at the most popular end of the scale grime really lost its way for a while. There were too many artists trying to make a quick buck. But maybe that’s not the case any more now. Like with the grime I hear on Rinse or tracks by newer MCs like Novelist or Meridian Dan and killer new stuff by Skepta and JME, it feels fresh again. What’s your take on this?

Kano: It seems that way to me as well. I think there was a time when a couple of people had a success and everybody – the artists and the labels – was trying to chase after a little bit more of that success. So you had labels trying to shape artists to be the next pop star. And with that comes a change of content, to make people fit in with the radio playlists, so it became about chasing that shit. It probably did lose it’s way a little bit with chasing the money. Which is understandable in a way because with a lot of grime artists they think, “OK, I can keep on doing what I’m doing but if I’m not getting too much attention, then how am I going to eat?” And then they see some other people getting up to all this other shit. Do you know what I mean?

I definitely kept my head down for a couple of years. Music just wasn’t going the way I wanted it to. Not just my music but music that I was hearing. People’s ambitions started to shift, to a point where it was a case of – do I fit in to be relevant and when you start thinking, “Maybe I’m the crazy one, maybe everyone else is right and maybe I need to start doing what everyone else is just so I can fit in.” Then you have to really step back and analyse what you’re in it for. Success is great but there are multiple meanings to the word success. I look at when I’m doing gigs and look at what old songs I still perform. You make loads of songs that come and go and you still end up performing the same tracks live. And every now and then you make a song that stays in the setlist and can’t be moved. I want to make those songs, not the songs that will get forgotten about. I want to make important records – important for myself and important for the culture as well. So I took a step back for a couple of years.

Well, no one’s going to accuse you of going after some massive cheesy pop hit with ‘Hail’. Because that tune is really heavy.

Kano: [LAUGHS] Yeah. That was tough man. The producer Rustie sent me this track and said that he was really influenced by grime when he was coming up; but he was obviously coming from a slightly different angle. The track wasn’t really grime though; it’s got the energy of grime but it’s different. For starters, it’s at 126 bpm, not at 140bpm, but most people wouldn’t even register that because of the way it sounds and the way I’m flowing on it. So he sent that to me and I got some guitars put on it because it felt heavy to me – I wanted to dirty it up even more. I just really went for it. Put some more drums on it. I put the Tempah T sample on it at the end. After I recorded it I realised it was a statement piece. It’s definitely what I’m about. It’s my essence. I was never, “OK, I’m a grime artist and I’m going to stick to the grime formula.” If you listen to my first album, it’s not all grime and at 140 bpm. It had a song like ‘Typical Me’ which had guitars on it. It sampled ‘War Pigs’ and was influenced by dancehall. I always wanted to work under the umbrella of grime but also see how I could twist it and see how I could make it mine and not just fit into the idea of what was expected of me.

The lyrics to Hail really relish in throwing up references to lots of very uniquely British styles of music such as drum & bass and dubstep – these sorts of music that originated in Britain and couldn’t have originated anywhere else. You bring up the idea of these styles of music not being recognised for how influential they are abroad.

Kano: It’s not that this music doesn’t get the kudos abroad, it’s more that I think we’re heavily influential to a lot of American music; a lot of rap music. We’re not afraid to say we’re influenced by Jay-Z or RUN DMC but it feels sometimes like they don’t want to say it but I can hear it. I can hear the dubstep influence on Watch The Throne. Even old tracks like [Memphis Bleek’s] ‘Is That Your Chick’… it just has to be. They’re influenced by drum & bass.

Tell me about the influence of live instrumentation on the album. Stylistically it covers a lot of ground but the one common theme musically is the use of live instruments.

Kano: Yeah, that’s what I wanted. I felt like a lot of music from my area was just synthetic man. I mean I love this music but a lot of it felt like it wasn’t lasting. You listen to a track that was made last year and it already sounds super dated. When I listen to classic records that have lasted the test of time, they do tend to have live instrumentation. And maybe that comes from playing with a live band or touring with Gorillaz or whatever but I wanted to make a record that a DJ could play but also they could be interpreted live as well. A track like ‘This Is England’ is still tough but sounds sick with those live drums and live brass and strings but a DJ could smash that as well. And that was kind of the thing I wanted to hit, I wanted to target that sweet spot.

Are you becoming more politically conscious and if you are is this being reflected in your music?

Kano: I probably am becoming more politically aware but I definitely am becoming more socially conscious. It’s not just a part of growing up… I’ve got mates my age who don’t give a fuck about it. It may be the circles I’m moving in. You talk about haves and have nots… well I see myself as being between them. I’ve sort of made it but I’m not crazy rich at the same time. And more importantly I can move between both worlds – so one day I’ll be working in the music industry and the next day I’ll be in the barber’s shop in Canning Town and someone’s about to get stabbed… Sometimes my life is so mad in that way. I can see both sides so vividly.

I feel guilty in a way… but I do take inspiration from that side of things. I absorb a lot of that energy. I’m affiliated to it. It feels a bit fucked up sometimes that it’s the negative that affects me in a positive way for my lyric writing and I’m always aware of that.

On several tracks you keep on returning to a very fundamental idea that if you are born into certain communities in Britain in certain geographical locations, then you are faced with some very harsh choices about just surviving, just keeping your head above water. Do you feel that over the last few years with people who are unfit being sent back to work, cutbacks to services and austerity in general that things are getting worse for people in these communities.

Kano: Yeah. It’s getting worse. At a time when you just need money just to survive. It’s hard. Being born in certain areas can determine what you do in life. And for most people it will work like that. Some people will break out of that but a lot won’t. And I’ve just been fascinated by the whole nature versus nurture thing. Was I always going to become what I was going to become or is it because of what I’ve experienced along the way. Those things fascinate me. A Kano from a rich family probably wouldn’t have become a rapper and even if he did, he would probably become a totally different type of rapper.

Would you say that New Banger is the most grimey track on there?

Kano: Yeah. ‘New Banger’ can be played in the clubs and it’s a great song to perform when I do shows But I intend to do all live brass for that main riff. I’m going to get that played on that but I didn’t have enough time to do it for the single. I had to have them out at the same time so they could just work off one another and counterbalance one another. It’s not grime grime but it’s 140bpm and grimey.

Can you tell me about the a capella final verse of New Banger?

Kano: “My mum went to school with all the gangsters, they didn’t call her Melrose they called her Casius.” It’s just about that whole being black and growing up in Canning Town and it being really white and racist as it was back then. When I sit with my family, sometimes they tell the stories of how they had to get accepted and what was happening before that happened. Just for them to get by. It puts everything into perspective and hopefully generation by generation it gets better. They remembered the times though when they would have to walk the long way to school to avoid trouble. But then they would remember the time when they would say, “You know what? Fuck that. The long way takes half an hour and this way takes ten minutes – we’re going to go this way.” And that’s why they used to call my mum Cassius because she used to get into mad fights. Even when I see older people in Canning Town now they pull me over and say, “How’s your mum? She was trouble!” [LAUGHS] That ‘No Dogs No Blacks No Irish’ thing? My family properly lived through that.

You’ve said that on the album that you’re looking back ten years to the period just before you got signed and that head space you were in. What was your typical day like back then?

Kano: I was living in East Ham, 86 St Olave’s Road. I went back there for the video for ‘Hail’. I was just like making beats and writing music. I shared a room with my brother, he was a DJ and we just used to do sets. D Double E would come over, Demon, Sharky Major, we were always keen to spit. Those were the days we were going to De Ja Vu once a week on Monday. I was doing a lot of raves around that time the Palace Pavillion in Hackney, more East London venues like EQ, [Stratford] Rex and all that. And just hanging out with mates. I was splitting time between East Ham and Canning Town.

What was the first time you performed in public like?

Kano: I must have been either 14 or 15. My brother used to do raves – he still does occasionally. And he put on this rave at Legends in Barking. He booked me and Demon. We were so excited… we got T-shirts made with our names on the back [LAUGHS] We took it so seriously! But when we got there I just shit myself. There weren’t that many people there because it was early. I think later on he had Maxwell D from Pay As You Go who was big at the time. And I still feel to this day like the less people there are, the harder it is to perform. And I don’t know if that is because of this particular day… the first ever time I grabbed a mic. But then there was another one in Romford and me and Demon went on – we got bullied by his cousin to do it – he made us do it. And after all the nerves, it felt good. So after you perform, you just go back to being in the rave but everyone knows you were the guy who was just up there…

Especially if you’ve got your name on the back of your T shirt.

Kano [LAUGHS] Yeah! That was the first time and I kind of jumped in at the deep end from there because then I made this song ‘Boys Love Girls’, which became like the begining to me really becoming a solo performer and I remember performing that at Palace Pavillion. And as soon as the song started people went nuts. And it became a bit easier when people already knew the song, I didn’t have to do so much winning over.

One of the guests on the album is Wiley who you first went up against in Jammer’s basement in Leytonstone.

Kano: I think I was about 17. I’d been doing a bit on the underground. And yeah, we were at Jammer’s because we always used to go and record tunes there or cut dubplates for people. They used to do that DVD, Lord Of The Mics there. A few people had already had clashes there. Me and Wiley was there one day with Esco, rest in peace, and everyone was… It was like being in school. Everyone was just egging each other on. “Go on! Go on! Would you clash him? Would you clash him though?” I was just thinking, “Ah shit…” But I wasn’t going to back down. I was confident in my ability back then but still this was Wiley… I fucking grew up listening to this guy. I realised that I could end up having the shortest career ever. He could end me quickly. But I was never going to back down. So he left and came back an hour later and everyone was like, “It’s on.” And then the cameras came out. And it was… Bam! I had to do it. It was the first time I’d clashed on camera and it was against the main guy. I looked back at it a couple of years ago… and I look so young! But not really intimidated. I was just doing my thing. Just taking my shot. I was just doing what we do I guess. And it was friendly still… we didn’t hate each other. It was friendly but it was competitive and that’s how it was back then. Anyone could clash anyone and you’d go back to being mates again straight afterwards. But I think I won.

Giggs is another guest on the track ‘3 Wheels Up’ – how do you know him?

Kano: I knew about Giggs a long time ago. When I first started going on tour around 2005, the guy I used to travel with, Getts, he would always be playing Giggs in the van so I became a fan like that. But didn’t meet him until around 2009 when we ended up doing a song together. I don’t really have too many friends who are MCs that I just see to hang out with. We don’t even talk about music that much. I’ll just call him, go round his house for Sunday dinner. We go out and eat and that. But I’m a big fan of his, I respect his craft. We made a song together for a mixtape some time ago. And he was always pencilled in to go on this record. I started off with a list of names that just got shorter and shorter. I wanted both Wiley and Giggs to be on the record because I see them both as pioneers. Wiley on the grime side and Giggs on the hip hop side. So to do a song with both of them was a real ambition.

I’ve got to ask you – does Giggs talk that deep in real life?

Kano: [puts on breezy Cockney accent] Nah, he talks like this innit? [LAUGHS] It’s really weird, he’s just got a regular speaking voice but when he’s recording, that’s how it comes out. It’s just natural for him.

I was wondering if there was any kind of similarity between you making Top Boy and you making your new album – because there’s a difference between Kane Robinson and Kano and a difference between Kane Robinson and Sully isn’t there? Are both things, kind of like acting?

Kano: No, no, no. I’d say that Kane and Kano are the same person when it comes to writing and recording the shit that I’m talking about but it’s more of an act when you go to perform the material. That’s when it becomes a performance piece and that’s more like acting. So the live shows are the most similar things to acting in a show like Top Boy. And other than that they are completely different. In the terms of recording a TV show and recording an album… they’re completely different but that’s just the way that I record an album. The way that I appear in Top Boy? That’s probably the way that Britney Spears records an album… you know? You don’t get much say! When you’re filming Top Boy, you can’t look back over it, you can’t add shit to the script, you just read it. And it’s hard because I’m a control kind of person when it comes to making a record and it’s hard to let go of that kind of control.

Did you learn anything that’s fed back into your music?

Kano: I think that vulnerability is key to connecting with an audience and that’s the main thing about acting. You drop everything at the door. Be completely vulnerable and don’t be scared to be vulnerable. And it’s not easy to do at all but knowing that you’re playing a character makes it slightly easier to do and maybe that did influence making certain tracks on the album where it was the same: be completely vulnerable. The only difference is, that on the album, it’s me.

Do you have to know where you’ve come from in order to know where you’re going?

Kano: Yeah, I think so definitely. but still I like to take where I’ve come from along with me. There’s a Jamaican phrase, “Get rich and switch.” You know that phrase!? “Get rich and switch!” Well hopefully if I ever get super rich I ain’t going to switch – it’s not in me. I love where I come from too much.

Kano plays Simple Things festival in Bristol on October 22