At a time when audiovisual performances are offering new and expanding territories for many modern musicians, Joshua White has something of a veteran’s touch. Dubbed the ‘forefather of VJ culture’ – a title he seems quite tickled by – White designed environments for the first generation of New York discotheques, before setting up Joshua Light Show in 1967.

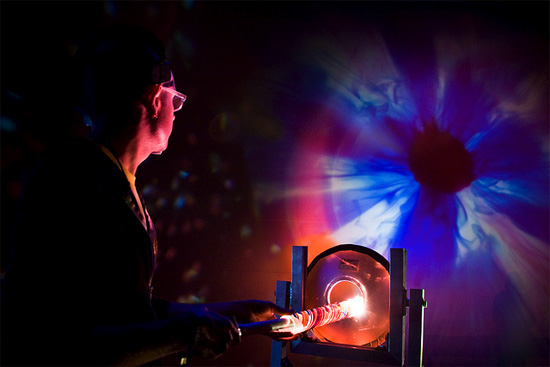

Their live show now is not too dissimilar to its original incarnation back when it first began. Infinite combinations of film, slides, inks, oils, colour wheels, mirrors and overhead projectors are expertly merged by White and a team of collaborating artists, producing a psychedelic alchemy of organic and otherworldly forms. For the audience, waves of colour settle on the screen, before inks come into view – visibly dropped from pipettes by hand – rippling and spreading as the music develops.

It’s hard not to feel the weight of 1960s nostalgia during a performance. The Light Show’s fantastic spectrum of colours brings to mind the most benign of acid trips – either imagined or remembered – but at times the light show is gruesomely visceral, conjuring up pulsing internal organs, Petri dishes and cell division. Its soft-focused abstraction allows audiences to project their own narrative: neon signs distorted by a rain-blurred taxi window, childhood motorway car journeys, blood draining from a murder victim.

Performing initially alongside classical and jazz musicians – in whom White sees parallels in his own approach – Joshua Light Show soon found a permanent home in the late sixties at Bill Graham’s Lower East Side nightclub Fillmore East. There he performed alongside the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Frank Zappa, Jefferson Airplane and The Doors, as well as producing visuals for Woodstock and the party scene in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy.

While working as a TV director and producer for 30 years on shows including Seinfeld, White continued the show on a smaller scale. More recently, increasing interest in VJing – driven in part by a new breed of multidisciplinary artists coming out of institutions like the Rhode Island School of Design, as well as by the YouTube-inspired necessity for musicians to think harder about their visual brand – led to renewed attention in the original light show.

Now seen as an artist in his own right rather than just an accompaniment to live music, White performs with a fluctuating team of fellow VJs, mixing original analogue techniques with high-spec digital technologies. It was this contrast that inspired Transmediale/CTM to invite the seven-strong crew to this year’s Berlin festival of digital culture, where they performed with unheard-of equal billing alongside Oneohtrix Point Never, Manuel Göttsching and Norwegian improv group Supersilent.

Although White himself was not involved in choosing the accompanying artists, the pairings could not have been more appropriate – the sprawling improvisations of all three artists lend themselves well to the light show’s gradual pace. In addition, White’s colour-saturated 60s light show visuals are strikingly mirrored in Oneohtrix’s Dan Lopatin’s YouTube echo jams, a reminder of just how influential his visual aesthetic continues to be on successive generations of musicians.

The Quietus caught up with White in Berlin, just before his performance with Oneohtrix Point Never.

The three of the artists that you performed with at Transmediale are all quite different, in sound but also in the structure of their music.

Joshua White: Yes, that’s by design. We wanted to make sure, as we were doing three performances, that each one would be completely different. The light show has a big palette but it’s not that big. We can do a lot of subtle changes in it but we’re working with the same tools, so what makes each performance different is the music.

Do you design each show especially for the artist, or is it just the music alone that makes it different?

JW: My approach will change but I won’t say at the start "OK, this is my vision", it will be what happens in the moment. The part that people can’t see is that we all are wearing headsets and talking to each other. We’re not talking about high art, we’re telling each other what we like and don’t like, and suggesting things. I could do it alone, but to be honest it’s more fun when someone says "Do a convection plate here", and we’ll say "good idea" or "not a good idea". It’s a great thrill for me, watching it self-direct.

So it’s very reactive to previous effects – especially as some of them are very unpredictable.

Let me give you an analogy – improvised jazz. When jazz musicians play together each one knows and trusts the other. Each musician needs to be good enough to be playing with the others and everyone needs to know the song. So they begin with, say, ‘April in Paris’, and each person can go anywhere they want because they’re all playing ‘April in Paris’. Usually someone’s the leader – in our case the music leads – and eventually it comes back and they restate the theme and the piece is done. We’re basically visual jazz artists with our own instruments. We’ve all listened to the music, but not albums and albums of it, but we know its basic direction. Then all you need to know is how you begin and how you end, and then you can do anything you want in between.

How does your role differ from the rest of the group? Are you a conductor or a participant?

JW: First of all my direction of the show is more generalized now, because the techniques that everyone is working on are techniques that I helped develop or, in some cases, invented. Each member of the group has a tremendous interest in all the aspects, but they specialise in one. So for me it’s just a question of looking at what everyone’s doing and adjusting. The truth is that I can look and just stare at it, which for me, at my point in my life, is very satisfying.

Is there a lot of preparation that goes into finding a structure and new effects for performances?

JW: We’re working with a certain palette, and within that palette there are infinite combinations. So for example Ana and Seth, who are people that host liquid effects, they work on them late at night and keep doing things that are unbelievable. Yesterday I took a walk with Alice and we couldn’t help buy some shiny material and boards to put it on. You go into light show mode where you evaluate every object for light show potential – a lot of stealing ashtrays from restaurants and things like that!

For me part of the magic of the show is that some of the effects are easy to work out where they come from, you see a hand and a pipette for example…

JW: That part is ok with me. I actually like when you see the hand, you see it dropping. It is accidental, but it’s an accident that makes it human. It says "I’m not programmed, I am not filmed, a human is putting their hand in."

I like how that human touch contrasts with some of the abstract effects that, for an audience that hasn’t seen backstage, it’s impossible to imagine what’s happening. Is that contrast important to you, to have a sense of alchemy there?

JW: Yes it is, but I don’t visualise myself as a wizard behind a curtain. The whole idea is that we put up a series of beautiful but somewhat ambiguous visual ideas. The audience listens to the music, which is 50% of the experience, and makes their own choices about what they’re drawn to, which I don’t have to know about. I guess my job is to make sure that what we do doesn’t upset or ruin your experience.

How do you see Joshua Light Show fitting in with the theme for Transmediale – in/compatible?

JW: What’s interesting to me, what I find fascinating, is that as you walk around Transmediale that theme is being realised, because it is our very incompatibility that brought us here. We are completely low-tech but it doesn’t mean we don’t have very sophisticated computers and very high-powered video projectors. But then again, you’re not looking at a movie. And like I said, that’s why I don’t mind a mistake, or something that shatters the suspension of belief – it just makes it better by comparison.

You’ve been performing as Joshua Light Show for a long time. I wonder whether public perceptions of VJing, and the way that musicians engage with visual artists, has changed since you started?

JW: When we first did this we weren’t part of the art world, we were not considered artists. We occasionally found ourselves being compared to the art world. People would suggest we were doing the same thing as Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, and my answer was "No, that was a bunch of crazy people running around in strobe lights making money at the door. We were making something else." In the early 2000s, a whole new group of curators came along and looked at the photographs as art, so now we’re ‘artists’. But back then we were performers.

Do you think your work needed to be committed to the page to make that distinction, or was it just time?

JW: Yes, I think so, but other things have been accepted as art as well. When we began, we were looked down upon – not that we gave a shit. We were 24. We were looked down upon by the art world because they thought the show didn’t really have any content, and classified it as music. The truth is the show pleased our audience, which were mainly people that came to hear the music. Now we’ve gotten more sophisticated because time has passed, but we still perform with the idea of pleasing our audience. We’re not here to piss them off.

What was it about the early 2000s that started people thinking about VJing in a different way? One thing that comes to mind is the change in visual culture around music in terms of the internet. If you’re putting music on YouTube it requires a visual, which perhaps encourages artists to think more about their visual footprint.

JW: It’s been going on for a long time, but everyone thinks about their visual image a lot more now. When we first started people came out with their jeans and played with their back to the screen. I mean, they did but they didn’t really care. Now people come out and do ‘shows’, and that identity carries on online.

Your Transmediale/CTM shows were live-streamed as well.

JW: I saw some of it and it looked wonderful. It’s amazing that people come to Berlin but now they don’t have to. It’s funny, because the reason that the Joshua Light Show continued and became the most famous was because of our decision to film it and edit it digitally later. I had gone to film school in the early 1960s so I could load up a 35mm camera with film. We didn’t shoot documentaries of the Light Show or the main performance because you couldn’t in those days. Initially film didn’t capture the high contrast and it was hard to work with, so we turned the projector round and shot the lightshow off a very small screen. I just had that footage and, as editing systems became more digital, I enhanced it and created what we called the loops. I’d sell them for stock footage, and when there was interest in doing a series of Summer of Love-type shows, they used some of it.

A show went to Florida in the summer of 2007 and my footage was hooked up on two small monitors in the back. The organisers noticed that everyone was gathering around, probably because my footage was not people smoking dope or a dark, grey slate. My stuff was actually what you thought [the 1960s] should be. As the show moved around, my part in it kept getting bigger and bigger until we got to Vienna, where it was projected right at the top of the stairs. When it came to New York the following year, it was the first thing you saw as you got in the elevator. I was very fortunate in that it became iconic.

One of the festival press releases refers to you as the ‘forefather of VJ culture’. How do you feel about that?

JW: I’ve been punishing her [the person that wrote it] by saying to her "You must call me ‘Herr Vater’ while I’m here"! I don’t take that part seriously because I know the light shows are about providing support for the music.

Why do you think your work became so iconic?

JW: I was in the right place and the right time when the music was just so good – Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin – it sounded so good and there was nothing to look at, people really wanted a visual experience. I also never had any pretensions about what I was doing. I was providing the visuals, but the visuals are half of the experience. I didn’t think I was making great art. There was never a solo tour, I would just take the visuals seriously and there was no job too big or no job too small. It has served me very well to relax and not take myself seriously – well, not take myself too intellectually.

Photos: © Genz, Lindner / transmediale & Ania Domanska / transmediale